China’s newest national military strategy provides further insight on the framework that Chinese leaders use for their routinely enigmatic decision-making processes. The current paper builds on previous military white papers, which necessitates a look to previous editions in understanding the most recent one. Comparing the 2013 Defense White Paper with the 2015 strategy shows a great deal of overlap, but more interesting than the party lines consistent over many years are the differences, including the absence of key issues, from the most recent document. A reading of China’s Military Strategy alongside an analysis of contemporary events in the Sino-Japanese relationship illuminates a subtle shift in Chinese strategy since late 2013 from the East China Sea toward the South China Sea in China’s own Southeast-Asia Pacific Rebalance centered on the Maritime Silk Road.

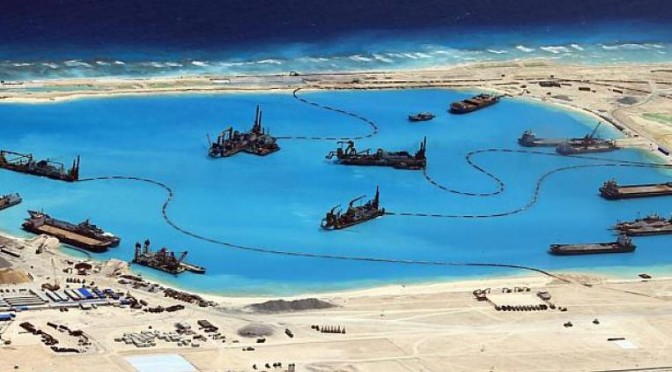

Controversial island building by the Chinese and surveillance flights by the U.S. Pacific Fleet Commander have highlighted the significance of South China Sea relations within the past few months, but the 2015 Chinese Military Strategy further reflects this importance. In the paper, China highlights their “South China Sea Affairs” that encounter the “meddling of other powers,” a point notably lacking from the 2013 White Paper given the long history of the dispute and the degree of scrutiny that decision makers put into these documents.

But observers may question why Chinese planners decided to undertake the hugely provocative project of island building and why the 2015 paper would touch upon it. Part of the reason may deal with the timing of the building with respect to other claimants. Vietnam began its land reclamation around 2010, and the Philippines followed suit with runway construction in 2011.

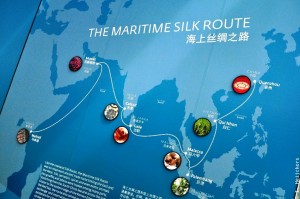

So China was not the first to engage in island-building activity (although the speed and scale of the projects vastly outweighs the Vietnamese and Philippine efforts); instead China, under the comparatively bolder Xi administration after 2012, decided to run full speed in the race to grow its claims starting in October 2013 when the projects were first spotted. This start date coincided closely with the One Belt One Road announcement in September 2013 and Maritime Silk Road announcement in October 2013, with the latter running directly through the South China Sea and near the disputed areas. Additionally, the October 2013 efforts post date the 2013 White Paper, published on April 16, 2013, allowing time for a strategic shift that was not solidified until after the document’s publication (or was perhaps deliberately omitted).

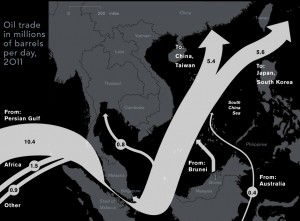

So, for China it appears the importance of island building in the South China Sea lies in ensuring secure maritime lanes for both its current trade and for the heightened flow that will come from the Maritime Silk Road. As a comparison of China’s land and sea economic trading shows, the nation is effectively an economic island, and the vulnerable flow through the South China Sea is the lifeblood of China’s economy. Should the nation lose control of that flow, its economy would be crippled, the consequences of which the Chinese people (and the Chinese Communist Party, which owes a great deal of political legitimacy to its economic growth) do not want to risk. The result: islands to enable enhanced oversight of the sea lanes.

As important as the addition to the 2015 paper, however, are its omissions. The 2013 paper depicts a “Japan (that) is making trouble over the issue of the Diaoyu islands,” but nowhere in the 2015 version is there an explicit mention of the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute. The only mention of Japan in the new strategy addresses the “overhauling [of] its military and security policies” (an understandable mention given the recent Japanese Diet bill increasing the scope of Self Defense Force operations) and its potential inclusion with the above South China Sea “meddling powers,” though the latter is not explicitly stated. The decision to remove an explicit mention of the Diaoyu islands dispute mention from the 2015 document is significant. This significant shift is reflected in recent reports of oil rigs in the East China Sea showing that China is choosing to literally not cross the line with Japan in this contentious geography. Statistical anomalies and shifting tactics aside, this is consistent with its deeds and not just its actions. If one is to make comparisons—albeit difficult given the different situations between East and Southeast Asia—a provocative statement toward Japan equivalent to South China Sea island building would be to cross the median line and assert China’s original stance regarding the continental shelf on the Japanese side of the line.

Instead, China sees the larger picture: the East China Sea is at a stalemate while the South China Sea remains comparatively free to shifts in the status quo. This couples with the decrease in Chinese patrols within Senkaku/Diaoyu waters beginning in October 2013 and coinciding with the beginning of Chinese island-building efforts in the South China Sea. If one were to draw an albeit difficult analogy, a provocation equivalent to island building in the South China Sea would be for China to literally cross the line and assert its original stance on Japanese and Chinese claims to the continental shelf. Yet, it appears that China is taking a holistic strategic view of regional issues and refraining from simultaneous confrontation.

There are a number of reasons why China might decrease its focus on Japan. Whether China feels secure enough in the region with the November 2013 establishment of its East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone or whether Chinese leadership have taken into account the increasingly interdependent economic relationship, the potential to warm the Sino-Japanese relationship, or too much perceived risk in the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands, their words and deeds suggest Japan is no longer China’s primary security focus. Instead, China’s military (or at least, its maritime forces, which the National Military Strategy states will be increasingly emphasized) is drawing resources away from the East and toward the Southeast to support the Maritime Silk Road in China’s own Southeast-Asia Pacific Rebalance.

For the U.S., this Southeast-Asia Pacific Rebalance warrants careful consideration of any substantial increase in support of Japan or major shift in Japanese posture (e.g., expanded operational scope for the Japanese Self-Defense Force [JSDF]). Since a shift in the current balance may force China to once again focus on the East China Sea, for both the U.S. and Japan this suggests the wisdom of measures to reassure China. For example, emphasizing that the JSDF’s increased scope does not imply a corresponding increase in hostile intent or the targeting of that scope against China.

With respect to the South China Sea, and extending the analogy between the East and South China Seas, awareness of this rebalance places more decision-making leverage in American hands. Should the U.S. want to deter China in these waters as in the waters surrounding the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands, stationing troops in the region, partnering with Southeast Asian allies, or reconciling with states in Southeast Asia and along the Maritime Silk Road are all potentially viable approaches. These approaches will become increasingly important as the Road is further established in the coming years and as China correspondingly shifts its focus to these waters; as China shifts focus to Southeast Asia, the U.S. must shift focus as well.

The new U.S. National Military Strategy falls in line with this thinking, describing how China’s “claims to nearly the entire South China Sea are inconsistent with international law,” and thus are a strategic focus of the U.S. However, conscious efforts must be made to maintain this momentum as China’s Rebalance appears to be a long-term project. This includes, as the Chinese Strategy states, further partnerships with states along the Maritime Silk Road as it expands, the groundwork of which will require diplomatic and political work today in preparation for the Road’s expansion. While other pressing issues (e.g., Russia, ISIL, etc.) top the list in describing the strategic environment in the U.S. Strategy, the American Asia-Pacific Rebalance must endure as the long-term strategy.

This interest in increased U.S. presence along the Maritime Silk Road is reciprocal. For Southeast Asian leaders, China’s rebalance marks the beginning of more vigorous Chinese engagement in the South China Sea and Southeast Asia as a whole. These nations must be prepared for increased Chinese presence and attention, and plan for higher levels of more geopolitical friction. Each nation’s approach will depend on their unique circumstances, but allowing U.S. counterbalancing forces into the region is one of a handful of options for adapting to the changing circumstances.

For all parties, tensions in the South China Sea present a serious challenge to both joint economic growth and regional security. While the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute will remain on China’s agenda, the evolving Chinese military strategy and Chinese actions suggest that South China Sea is the next area of focus for the rising nation. This gives the region and the states within it an increasing strategic priority that cannot be ignored.