By Jeong Soo “Gary” Kim

The Japan Maritime Self Defense Force (JMSDF) possesses a modern and highly capable fleet, including light carriers, large AEGIS destroyers, and advanced conventional submarines which are renowned for their size and stealth. While individual Japanese naval vessels and their crews are certainly world class, Japan’s unique approach to naval industrial base strategy is often underappreciated, especially its submarine industrial base. This approach relies on three deliberate policy pillars:

- Ensuring an extraordinarily stable production system for new boats,

- Decommissioning operational boats with plenty of service life left in them, and

- Maintaining these retired submarines in training and ready reserve fleets.

This industrial policy admirably balances cost, readiness, and wartime surge capacity.

Pillar 1: Stable Production Capacity

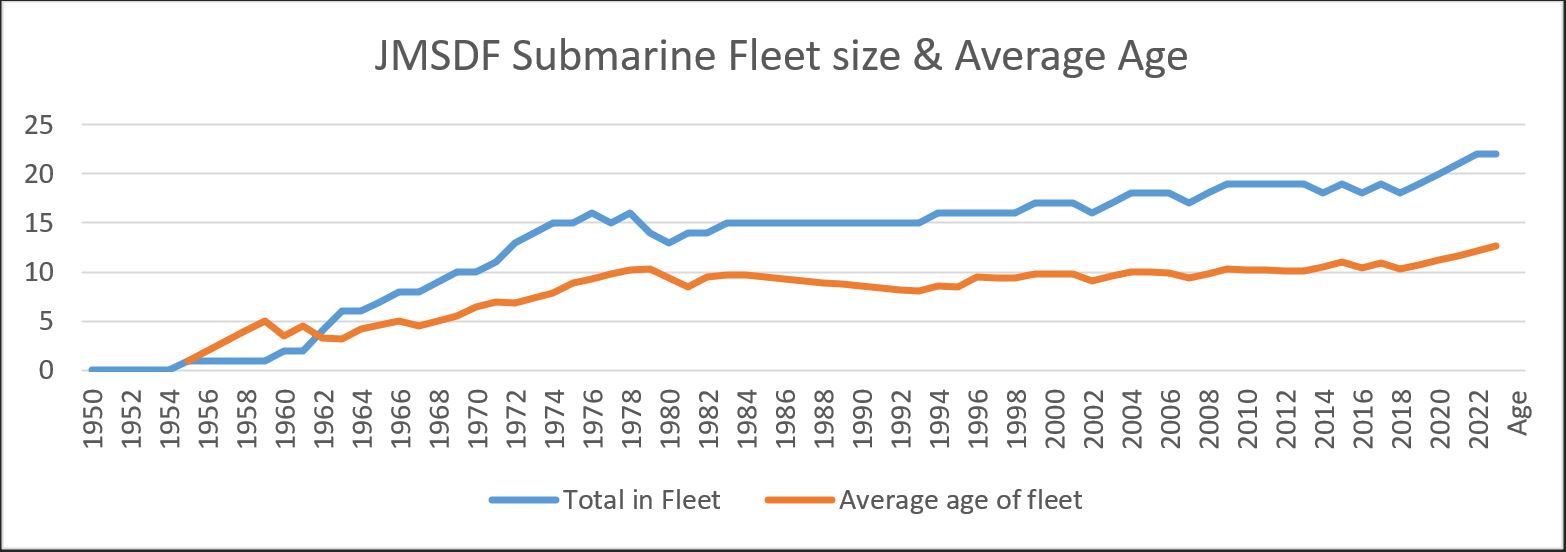

The JMSDF received its first submarine, the JS Kuroshio (ex-USS Mingo) as Foreign Military Aid in 1955. Soon after, the JMSDF started ordering domestically produced submarines based on both Imperial Japanese Navy and U.S. Navy designs. Starting in 1965, the JMSDF consistently built ocean-going fleet submarines, and by 1980 starting with the Yushio-class of submarines, Japan had established an incredibly stable submarine industrial base. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Kawasaki Heavy Industry’s shipyards in Kobe each produce one boat every two years. With the exception of 1996 (due to the great Kobe earthquake of 1995) and 2014, Kawasaki or Mitsubishi has delivered a submarine on March of every single year like clockwork. This production scheme has held steady through the massive expansion of the Soviet Navy during the 1980s, the peace dividend era of the 1990s and 2000s, and even through the PLA Navy’s surge in the 2010s and 2020s.

Another stabilizing leg of the JMDSF’s submarine industrial base is the forward-looking and well institutionalized research and development scheme. For example, detailed design for the current Taigei-class of submarines kicked off in 2004, even before the previous Soryu-class was laid down. Detailed engineering for a follow-on class, including such features as pump jet technology, was already in the works when the JS Taigei entered service in 2022. Furthermore, when the JMSDF implements new technology, like Air Independent Propulsion (AIP) or large lithium battery packs, it inserts these technologies into an existing class of submarines to validate technical maturity. For example, in 2000 the JMSDF retrofitted a conventional, Harushio-class submarine, JS Asashio, with a Sterling-type Air Independent Propulsion (AIP) module to test its effectiveness before applying the technology to the future fleet. Similarly in 2020, Soryu-class submarines JS Oryu and JS Toryu were fitted with large lithium-ion battery packs instead of the Sterling AIP modules in anticipation of the lithium-ion power pack transition in the Taigei-class.

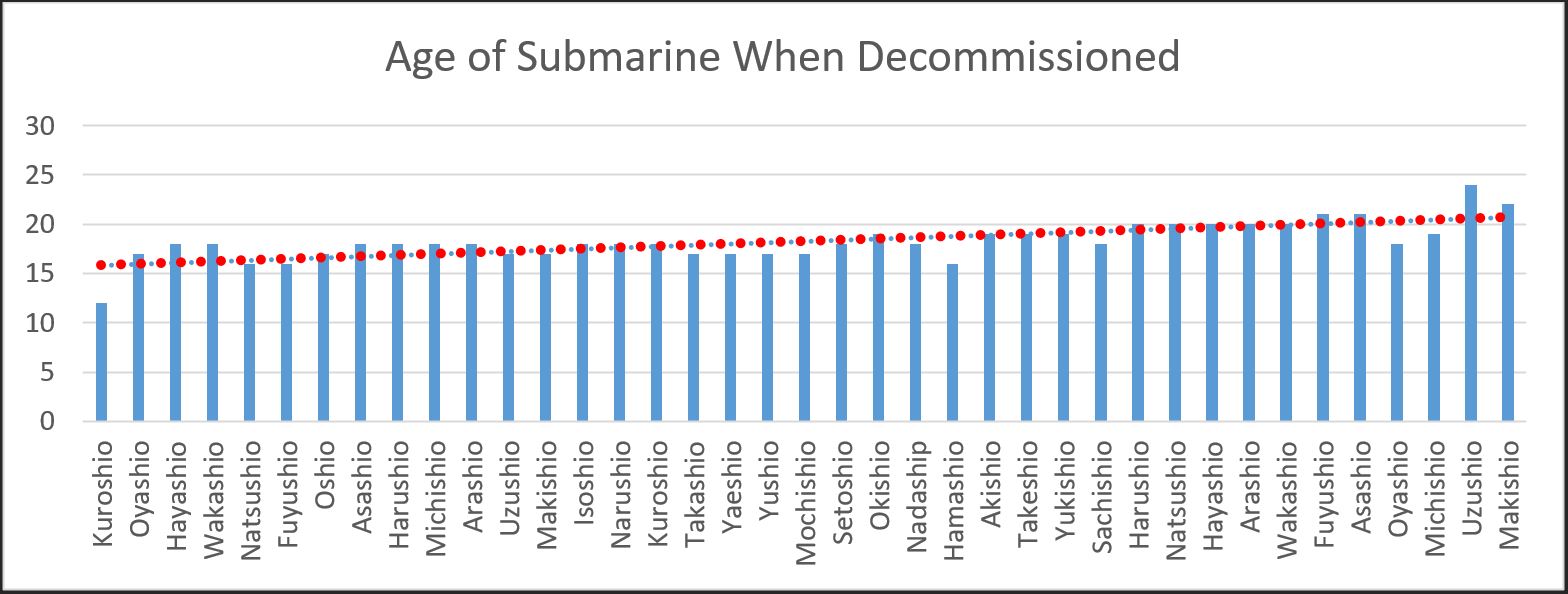

Pillar 2: Unique Utilization Strategy at the Operator Level

The JMSDF’s submarine utilization system is unique and may seem odd to American and other Western Navies. While Japanese submarines are well-built and likely could serve as long as their American counterparts (35-40 years), they serve around 18 years before being decommissioned or transferred to training status. While most navies try to sustain submarines as long as economically feasible, the JMSDF “prunes” serviceable submarines out of its operational fleet in order to maintain the number of boats required in Japan’s maritime strategy. For example, between 1980 and 2018, the national strategy called for 18 submarines in the operational fleet, therefore most submarines were decommissioned between the 17-20 years of service to achieve this fleet goal. Starting in 2019, in order to match China’s rising naval power (and perhaps to hedge against the U.S. submarine base’s sluggish production increase), Japan’s maritime strategy increased its submarine requirement to 22 submarines in the operational fleet, and the JMSDF raised the “retirement age” of its submarines from 18 to 22 years until annual submarine production rate allowed the fleet size to reach 22. Officers in the JMSDF’s ship repair unit describe maintaining older submarines as “more costly, but not particularly difficult”, implying that if operational needs dictate, they could increase the number of operational submarines without having to increase the production rate.

Another unique aspect to the Japanese submarine industrial base planning is that submarines typically do not go into an extensive mid-life refit like their American counterparts. JMSDF leaders cite that overhauling older vessels can often be unpredictable and lead to schedule growth, as submarines can be in much worse material condition than anticipated. They admit that conducting a mid-life upgrade could save cost in peacetime, but the current system that prioritizes new construction ensures more stability in the submarine industrial base. On the ground level, JMSDF ship repair officers cite that cutting holes into a pressure hull and then replacing major components in already tightly packed submarine is time consuming, and believe that new submarine construction “delivers more submarine sea power per man-hour worked” than conducting a midlife overhaul. They jokingly called this practice similar to the “Shikinen Sengu”, which is a ritual where one of the most revered Shinto shrines in Japan, Ise Shrine, is traditionally torn down and rebuilt every 20 years.

Pillar 3: Consistent Supply of Reserve Submarines

Another benefit of consistent production and early retirement is the ability to keep several reserve submarines in good material condition on reserve prior to final decommissioning and disposal. Typically, when submarines are decommissioned from the operational fleet, they are transferred to the training squadron and then consistently sail to train and qualify sailors prior to assigning them to operational boats. The training submarine fleet not only helps supplying the operational fleet with sailors already equipped with sea time inside a submarine, but also allows boats to be quickly transferred back to the operational fleet whenever new construction and delayed decommissioning cannot meet requirements. While the JMSDF has yet to recommission a training submarine back to active service, it has transferred older destroyers, the JS Asagiri and JS Yamagiri, from the training fleet back to the operational fleet in 2011/2012 to meet increased operational surface vessel demand. It is not unimaginable that the JMSDF would be willing to use its training submarines in a similar manner during a period of surging demand.

Furthermore, when submarines stop sailing with the training squadron, they stay on a reserve status receiving a certain amount of maintenance until they are finally stricken and disposed of. The number of submarines kept in this status is not well known, but parts are typically not salvaged to sustain other boats for a number of years. If submarine demand were to outstrip operationalizing the training submarines, the reserve boats could possibly be put out back to sea after some period in maintenance. Consequently, the combination of operationalizing the training and reserve submarines could give the JMSDF the ability to surge up to four additional operational submarines without accelerating its build schedule, which would constitute an impressive 20% increase in capability from the current fleet of 22 boats.

Conclusion

All in all, Japan sustains an advanced, powerful conventional submarine fleet staffed by dedicated, overworked sailors, and supported by a robust, stable shipbuilding industry. Considering how quickly a shipbuilding industrial base atrophies without consistent inflow of new construction orders, the Japanese method of consistent production and fleet size control through early decommissioning may prove to be a viable template that even the U.S. Navy can incorporate into its long-term naval shipbuilding plan.

Jeong Soo “Gary” Kim is a Lieutenant in the U.S. Naval Reserves and currently a student at the Lauder Institute at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania earning an MBA and MA in East Asian studies. He previously served with the Seabees of Naval Mobile Construction Battalion 5, and with NAVFAC Far East in Sasebo, Japan. He graduated from Columbia University with a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering and a minor in history.

The author would like to give special thanks to LCDR Hiroshi Kishida of the JMSDF’s Sasebo Ship Repair Facility, and various junior officers serving in Sasebo-based ships for assisting with the research for this article.

References

Dominguez, Gabriel. “Recruitment Issues Undermining Japan’s Military Buildup.” The Japan Times, The Japan Times, 2 Jan. 2023, www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/01/02/national/japan-sdf-recruitment-problems/.

Kevork, Chris. “The Revitalization of Japan’s Submarine Industry, From Defeat to Oyashio.” NIDS Journal of Defense and Security, 14, Dec. 2013, 14 Dec. 2013, pp. 71–92.

Ogasawara, Rie. “Observing the Horrible State of JSDF Military Housing through Photos.” ダイヤモンド・オンライン, 27 Sept. 2022, diamond.jp/articles/-/310137?page=2.

Takahashi, Kosuke. “Japan Launches Fourth Taigei-Class Submarine for JMSDF.” Naval News, 17 Oct. 2023, www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2023/10/japan-launches-fourth-taigei-class-submarine-for-jmsdf/.

일본 신형잠수함 타이게이(大鯨)함 진수의 의미 (Implications of the JMSDF’s New Taigei Class of Submarines), Korea Institute for Maritime Strategy, 11 Dec. 2020, kims.or.kr/issubrief/kims-periscope/peri217/.

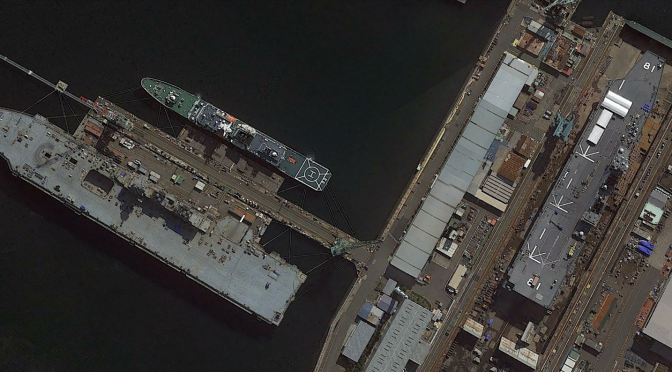

Featured Image: Launch Ceremony of SS Taigei. (Japanese Ministry of Defense photo)