By Bret Perry

If you’re in the Navy or elsewhere in the defense space, Larry Bond most likely influenced your pursuits.

Whether you’ve poured over one of his explosive techno-thrillers co-authored with Chris Carlson or spent hours trying to break the GUIK gap in their classic Harpoon war game, Bond and Carlson have most likely fed your intellectual interest in defense issues while keeping you entertained.

Larry Bond and Chris Carlson joined me to discuss a wide range of topics, including their recently published Red Phoenix Burning (reviewed by CIMSEC here), the growth of the techno-thriller, war gaming, distributed lethality, and their favorite books.

BP: You wrote Red Phoenix, your second book after co-writing Red Storm Rising with Tom Clancy, nearly 25 years ago. What drew you back to the same fictional universe and Korean conflict with Red Phoenix Burning?

In the 1980s, the threat was all about the DPRK, with one of the largest armies in the world, invading the south. They’d done it once, and would certainly do it again if they thought they could get away with it. But since then, the North has suffered terribly under the Kims. It may be that any closed society, so utterly corrupt, will eventually weaken and fail, and that’s a much more likely scenario these days. Red Phoenix Burning isn’t about an invasion of the south, but a collapse of the north, creating a humanitarian crisis as frightening as a military one.

In Red Phoenix, besides some of the special forces raids, much of the air and ground combat seemed conventional? How is Red Phoenix Burning different? What drove these decisions?

The battle scenes in Red Phoenix were keyed to what most people call a “conventional” war: WW II with better weapons. There are actually very few pitched battle scenes in Red Phoenix Burning; much of the fighting happens off-page. It’s the consequences of those battles, especially the fighting in Pyongyang, that forces the characters to act.

You’ve written/co-written quite a few techno-thrillers featuring large conventional conflicts in Central Europe, Eastern Europe, South Africa, the Korean Peninsula, and more. What drove you to write about the Korean Peninsula, especially after you have already done so once?

My co-author Chris Carlson has discussed this scenario with South Korean intelligence officials, and it’s one of their biggest concerns. We liked the characters in Red Phoenix, but really never planned a sequel back then, because who would want to read about a third invasion? But what about something as unexpected as a coup that leads to a North Korean civil war?

Your readers often praise you for the extensive research that goes into your books. As you’ve already written about a Korean conflict 25 years ago with Red Phoenix, in terms of the tactical and strategic security threats, what are some of the most significant changes you have observed?

The more we learn about North Korea and the regime that rules the country, the more it sounds like an organized crime family, and less like a government. In Red Phoenix we depicted the regime as a Stalinist dictatorship, but still a recognizable government. Revelations about institutional counterfeiting and drug manufacturing, as well as arms smuggling and money laundering, show that the regime will go to any length to get foreign exchange, which flows not to the citizens, but to the top leadership. And, of course, the big new strategic threat is North Korea’s nuclear weapons capability. Although it is still nascent, any nuclear capability changes the very nature of a conflict in the region significantly.

What’s been the reaction out of South Korea, and DPRK, to your past work and what do you expect from Red Phoenix Burning?

We’ve never heard from any Koreans about the story, but I’ve personally spoken to a lot of U.S. service members who tell me the book was almost required reading for American military in the theater. They’re polite enough to avoid mentioning whether it’s for comic relief, but they’re reading it.

In Red Phoenix, the North Korean regime did not possess nuclear weapons. However, as Red Phoenix Burning takes place in the modern day with the North Korean regime maintaining a small arsenal of nuclear weapons, how does this impact the conflict in the novel—without giving away too many spoilers.

The North’s possession of nuclear weapons is a complete game changer, as it is in any conflict. The fact that there are so few, of questionable reliability, and with primitive delivery systems, doesn’t change the basic fact that they can cause untold casualties. Indeed, because they have so little military utility, they would probably be used as terror weapons. The North Koreans also have a lot of chemical weapons, which can be almost as horrible, and the regime is irresponsible enough to use them.

You’ve been authoring techno-thrillers for a very long time, Tom Clancy called Larry the “new ace” of the techno-thriller genre. What are your opinions on how the genre has evolved from its origins now that information is widely available and civilian technology outstrips military innovation? Where do you think it will go?

Information is much easier to find now, not just about weapons, but settings, organization, all kinds of useful stuff. This can mean a lot more detail, which is not necessarily a good thing. It can provide more depth, or even a plot angle that you might not have known about before. It’s a given that people reading military thrillers enjoy the action and the hardware, but you have to provide a solid story, with realistic characters, or it’s just bullets whizzing back and forth to no purpose.

We’ve seen a recent trend in which defense analysts and thinkers have explored how fiction can better inform real-world debates on national security issues. What role do you think fiction plays in this discussion? What are its strengths and limits?

Having read a fair number of security papers and monographs, presenting information as a fictional scenario can engage the reader’s interest and improve comprehension, as well as getting your idea to a wider audience. The use of fiction to present a military-related argument goes way back. While General Sir John Hackett’s the Third World War (1979) was a recent example, there were books written in the 1920s (Bywater’s The Great Pacific War, 1929) and well before World War I (The Battle of Dorking, Chesney, 1871) that described a major conflict between nations. All these authors had things to say about the military, and used fiction as a way to share their thoughts. When an author puts together a plot, he/she pretty much knows what happens and when. Since we have a pre-established ending in mind, some of our assumptions and plot twists seem brilliant to some readers, but contrived to others. But it is the discussion on these points that has the potential of producing the greatest fruit, as it forces the investigation of alternative possibilities.

Following off of the previous question, it was recently revealed that Ronald Reagan advised Margaret Thatcher to read Red Storm Rising, which you coauthored with Tom Clancy. When you first learned of this, what was your reaction?

I hadn’t heard about that before. I hope it’s true. The most interesting story I heard about the influence of RSR was that the Icelandic government renegotiated its treaty with NATO. The old one was cumbersome, with even the smallest change to NATO’s forces (e.g., reinforcements) requiring approval by the Foreign Minster. Also, the Naval War College asked for my write ups of the wargames we played to research Dance of the Vampires, a chapter in the book.

One characteristic that separates your work from others is how you account for a wide range of factors, not just limited to military ones, but also political and economic aspects. Can you describe how you go about accounting for all of these factors and storyboarding?

We both feel that factors like politics and economics are what drive and provide the goals to military actions. While you can write very good fiction about the guy in the foxhole, we want to show the higher-level decisions (and mistakes) that give readers the big picture. As we plot out the book, we stop at each dramatic beat and ask ourselves how each player would react, and indeed, do any new players need to appear.

All of this requires that we read a lot on the countries of interest in a particular novel we’re working on. It’s not uncommon to find us pouring over books, think tank articles, professional journals, or talking to academics about aspects of our plot. The trick is to provide the reader enough background to show how politics, economics, and war are related, but not so much that we get into the weeds with detail—especially as many of these details are hotly debated within government and academic circles.

You have an extensive history of co-writing books. As they entail large, complex geopolitical and military subjects, can you explain how the cooperative process works? Any working tips for creative partnerships?

Co-writing definitely takes more effort than solo writing. I like it because there’s someone to bounce ideas off of, and to go “Auugh” with when you’re behind schedule. We’re systematic, first creating a treatment that the publisher signs off before we get a green light. That gets turned into a chapter-by-chapter “blocking.” Since we’re keeping track of multiple plot threads, often in different parts of the world, it’s mandatory if you don’t want to tangle up in each other’s prose. After the blocking is finished, we can take alternate chapters and start gluing words together. We then review each other’s work, hash out any differences, and move on. And, no, it doesn’t constrain the creative juices between us. We’ve both surprised the other by a slight plot twist that emphasizes a character trait in one of our heroes, or even a villain. Character growth is something we really try to deliver in our writing.

How has your research process changed from Red Phoenix to Red Phoenix Rising?

The Internet is the most obvious change, and is good not only for looking up military details, but grammatical rules. I didn’t sleep through my 7th grade English class, but being able to quickly look up the proper way to use a semicolon, or how to spell “Kyrgyzstan” is a definite help. Equally powerful is Google Earth. Being able to look at satellite imagery of the terrain you’re writing about is a great aid. Especially as hand-held photos of specific objects, buildings, streets, parks, etc, are keyed to the area you’re looking at. It’s very true that a picture is worth a thousand words.

The bottom line is don’t make things up unless you have no other choice. Accurate descriptions resonate with readers, and this helps them to become more involved with the story. Bond’s first law of research is that it’s easier to describe the real world than it is to make something up, and then have to keep it straight in your mind.

As the creators of the Harpoon series, you both have extensive wargaming experience as well. What role does this play in your fictional writing?

A good wargame tries to tell a story, usually about a specific historical event, but it is still a story. After board games and miniatures on a terrain board, something called “role playing” appeared in the 1970s. Most of the players assume fictional identities in some fantasy motif, be it an elf, mage, or whatever, but one player, the referee, tells the others the setting and what they see and hear. The players describe their actions to “the ref” who adjudicates their actions and describes the results. It’s interactive storytelling, with a heavy dose of improvisation thrown in. It’s great practice. Other things that wargaming has provided is a general sense of history and the military’s role, and also the wide range of results that are possible from replays of a single battle.

For the two of us in particular, designing wargames help us understand the basics of how some military piece of equipment works as part of a larger force. We also know where some of the skeletons are buried, like why a system didn’t work as advertised, and we can pull them out of the closet when we need a neat twist in the plot.

There has been a fair amount of recent commentary on some of the challenges with wargaming, and where it should go. What are your opinions on this?

Commercial wargaming is a recreational activity, and fashions come and go in any industry. There’s a constant demand for innovative products, which can create not just new games but entire new genres. Miniatures games go back well before H.G. Wells’ book Little Wars, and board games to Kriegspiel in the 1870s, but in recent times we’ve added role-playing, computer games, collectible card games, and LARPing. Grabbing the players’ interest (and his dollar) will be a constant struggle.

From our own personal experiences, wargaming has a fantastic training and education capability. We’ve watched more “light bulbs” go on when players start to understand and appreciate a particular historical situation. A good game brings history to life and is far more instructive than just reading a dusty textbook about a particular battle. Wargaming, done properly, can be very useful for basic familiarization, looking at alternative courses of action, even analysis. The concept of wargaming is currently on the upswing, but we’ll have to see if this new appreciation is a true change in perception, or just a fad.

Recently, we have seen countries leverage irregular maritime forces and other unconventional methods. From a wargaming perspective, can you describe how you account for these different challenges?

They’re difficult to model in a conventional “force-on-force” game. Usually, one patrol craft plus one narco-boat equals one drug haul. The trick when there’s little random chance in the encounter itself is to model some other part of the process: investigation or detection, for example. The designer has to have a clear picture of the game’s goal. Is it simply to understand the narcotics problem? Or are they evaluating alternative strategies for enforcement?

Due to this maritime security forum and the fact that you both have Navy backgrounds, I have to insert a Navy question here. In terms of future procurements, operating concepts, doctrine, etc., what excites you about the future? Railguns? Lasers? Distributed lethality? Why?

Unfortunately, railguns and lasers are still more science fiction than fact. I equate the first “operational ” laser aboard USS Ponce with the first aircraft flight from a warship by Eugene Ely in 1911. The nature of lasers and railguns will prevent them from replacing other major weapons systems for a long time, if ever. Missiles, as useful as they are, never completely replaced guns. For example, railguns have tremendous speed, but you actually have to hit the thing you’re shooting at. They don’t have proximity fuzes the way gun projectiles do. Minor angular errors in aiming become miss distances that increase with range. Small guns deal with this issue by keeping the range short and using rapid fire, but is that what railguns are supposed to be doing? We don’t think so, given the barrel life issues railguns have to overcome.

Also militarily effective railguns and lasers require huge amounts of power, something that is still under-appreciated in ship design. It’s going to take some time, and a lot of money, to solve both the system and ship-based issues before these new systems are widely deployed.

Distributed lethality is an interesting idea, but most of the articles sound a lot like a Dilbert cartoon with too many buzzwords. The Soviet Navy first implemented a crude capability back in the early-1970s, which has since matured to the third generation “Mineral” system. The Chinese Navy purchased, reversed engineered, and fitted Mineral on many of their surface combatants (Type 054A FFGs, Type 052C and 052D DDGs). Despite the favorable press given the long-range Tomahawk shot, or the recent SM-6 anti-surface mode demonstration, there is still no discussion on how these weapons are to be targeted. There appears to be an unspoken assumption that the information will just be there when needed—not the best of assumptions. The real drivers these days are stealth and electronic warfare. Both relate to finding the enemy, or preventing him from finding you, which is still the most important part of a fight at sea.

Since asking what your all-time favorite books are is too hard of a question, what are some of your current favorite books?

Larry: I’ve read couple of really good general naval history books lately. The Second Pearl Harbor, by Gene Salecher tells about a little-known fire and explosion aboard navy sips preparing for the invasion of Saipan. Combat Loaded is the story of a single amphibious assault ship, USS Tate, from her commissioning through and after WW II. Both were fun reads. I gave both good reviews in the October issue of ATG’s newsletter, The Naval SITREP.

Chris: I’m a huge fan of technical histories, and have just about everything written by Dr. Norman Friedman, although a recent book, Fighting the Great War at Sea: Strategy, Tactics and Technology, is my current favorite—but that will probably change when I start reading his new British battleship book. I also enjoy good general naval histories as well. And although Arthur Marder has come under attack by contemporary revisionist historians, his five-volume set, From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow, on naval warfare during WWI is still one of the best histories out there and fortunately, now back in print through the U.S. Naval Institute.

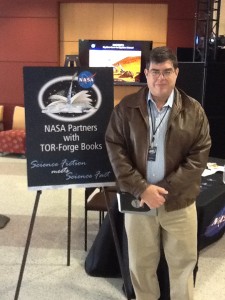

Larry Bond and Chris Carlson are the bestselling authors of the Jerry Mitchell series, Lash-Up, and now Red Phoenix Burning. Larry and Chris are the lead designers of the Admiralty Trilogy wargame system, that includes the long time classic—Harpoon modern naval miniature game. Both Larry and Chris are former U.S. Navy officers.

Bret Perry is a graduate of the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. The comments and questions above are those of the author alone and are presented in his personal capacity. They do not necessarily reflect those of any organization.

The author would like to express his thanks to August Cole for his assistance with this interview.

Featured Image Credit: Battlefield 4 Concept Art Team Robert Sammelin, Mattan Häggström, Eric Persson, Henrik Sahlström, Sigurd Fernström, Electronic Arts.