Congratulations, Singapore! In 2020, the city-state will operate the Indo-Pacific’s most advanced, non-nuclear-powered submarines. For China, these submarines present a challenge, however for Germany the deal provides the potential for greater security policy access to maritime Asia.

Type 218

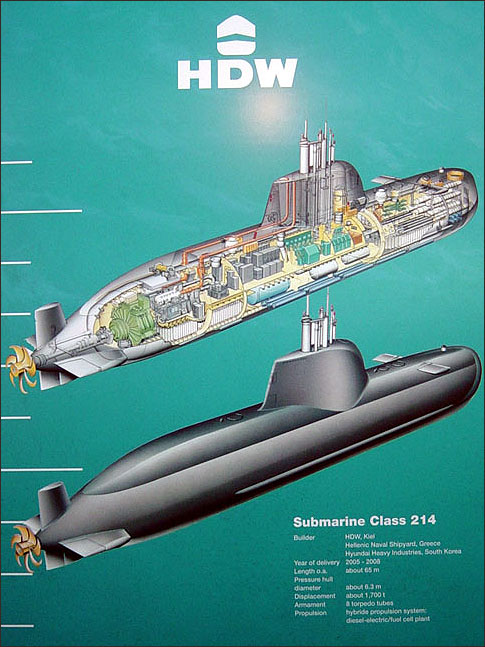

In early December, German shipbuilder Thyssen announced that Singapore’s navy had contracted two Type 218SG U-boats, a variety previously unknown. While the Type 216 concept has been in public discussion Type 218 had not. As it seems, Type 218SG is an improved version of Type 214, adjusted to Singapore’s specific needs, thus the “SG” suffix. Given its size and operational profile, Type 214/218SG subs are very well suited for operations in coastal waters, such as those around Singapore. Thyssen’s offered Type 216 concept is would have been too large.

Thanks to the air-independent propulsion (AIP) fuel cells the U-boat operates almost noiselessly like a nuclear-powered submarine, but without the heat signature caused by the reactor. In consequence, by 2020, Singapore will receive the most advanced non-nuclear-powered submarines in the Indo-Pacific.

Why Singapore Needs U-boats

Lately, international attention has largely been on aircraft carriers and, through China’s ADIZ, with air forces. However, Asia’s arms race takes pace underwater as much as it does on the surface. China is expanding its fleet of nuclear and conventionally powered attack submarines in quality and quantity and the U.S. will commission even more new Virginia-class nuclear subs.

Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, Indonesia, Australia, the Philippines, and Pakistan all maintain programs to start, modernize, or expand their submarine fleets. South Korea has already been a customer of Germany’s submarines. Especially small countries, who are missing the resources and capacities for large expeditionary fleets, will respond to China’s increasing capabilities by expanding of their submarine forces.

The U.S. and Britain will favor ally Singapore’s procurement of top-of-the-line German U-boats, but the purchase will certainly not please China’s navy. All Chinese warships underway to the Indian Ocean by the far-most economic route have to pass the shallow waters around Singapore, thereby coming in range of the barely detectable 218s.

The purchase of a German product also helps keep Singapore’s fleet interoperable with Western navies. For the West this is advantageous in the event that continued Chinese “assertiveness,” spurs the formation of new coalitions in Southeast Asia. Japan is already pursuing that track. Given China’s desire to establish an ADIZ in the South China Sea, at least one aircraft carrier would have to transit to the south of the South China Sea to enforce it. China’s fighter jets lack the range to launch from the mainland and aerial refueling capabilities are too immature. Thus, Singapore’s Type 218s would pose a serious challenge to any Chinese carrier task force.

How far China has advanced in sonar techniques and submarine detection is hard to say. If German Type 212s can make their way through the anti-sub-defense of a U.S. aircraft carrier, the even more advanced 218s should have no major difficulty embarrassing the Chinese navy.

Yet just two 218s will not be enough because Singapore’s navy also has an Endurance-class LPD and surface warships to protect. One rule applies to warships as well as submarines: one at sea, one in the yard, and one developing its readiness. Of course, the Singaporeans know that. Thus, given a successful program development, we will likely see an order of a second tranche.

Strategic Value for Germany

The announced deal is also a win for Germany. Besides the good deal for the German defense industry, the secured jobs, and the revenue, the deal’s strategic value must also be examined. By purchasing amphibious landing ships, new frigates and the F-35, Singapore, with its central geo-strategic location, is on the way to become a military powerhouse. It is therefore in the interests of a maritime trade-dependent nation like Germany, to have good relations with Singapore, as it inhabits one of the world’s most important ports.

Germany has not yet had any maritime security access east of the Malacca Strait in Southeast Asia. Even its role in the Indian Ocean has remained unusually limited. With the further pace-taking maritime arms-race in Southeast Asia, Germany now has a bright foot in the door. In addition, Singapore will become dependent after 2020 on German spare part deliveries.

It should be noted that a submarine deal with South Korea, to this day, has not produced any immediate strategic value or results in practical security policy. Through two customers instead of one that could change, especially as Germany pursues additional export deals in the region.

In addition to the potential for these lucrative arcontracts, Germany has an interest in a stable, peaceful maritime arc running from Singapore and Vladivostok. China’s re-armament, coupled with a more assertive military doctrine, and its aggressive enforcement ensures the opposite. Since one can doubt U.S. resolve thanks to the Obama Administration and the federal budget, the countries of the region must be able to balance China’s rise, at least partially, by themselves. Therefore, German-built subs can surely do their share.

Felix Seidler is a fellow at the Institute for Security Policy, University of Kiel, Germany, and runs the site Seidlers-Sicherheitspolitik.net (Seidler’s Security Policy).

Follow Felix on Twitter: @SeidersSiPo