Although much attention has been directed toward the uncertain fate of the Mistral-class amphibious assault ships that were being built in Saint-Nazaire, France for export to Russia, there has been considerably less reporting on Brazil’s quiet naval expansion. The Brazilian Navy has frequently been dubbed a ‘green-water’ force to distinguish it from conventional ‘blue-water’ or ‘brown-water’ navies. Whereas a blue-water navy is concerned with operations on the high seas and engaging in far-ranging expeditions, brown-water navies are geared toward patrolling the shallow waters of the coastline or riverine warfare. Green-water navies, however, mix both capabilities, focusing mainly on securing a country’s littorals but also retaining the ability to venture out into the deep waters of the oceans.

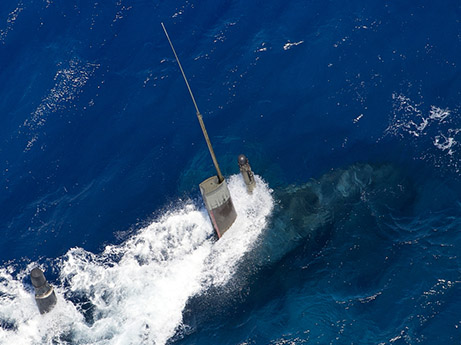

For several decades, this green-water label has been accurate to the Brazilian Navy. Although possessing a vast array of inland patrol ships and river troop transports to exert sovereignty over Brazil’s many rivers and drainage basins, the Brazilian Navy also boasts the BNS Sao Paulo, a Clemenceau-class aircraft carrier purchased from France in 2000. But there has recently been a shift in Brazil’s maritime priorities, suggesting that it may soon be more accurate to regard the Brazilian Navy as a blue-water force with some lingering vestiges of brown-water capabilities. Begun under Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, President of Brazil from 2003 until 2011, and intensified under the Dilma Rouseff’s current government, Brazil has been on a shopping spree for military hardware. Although this has included procuring 36 Gripen NG multirole fighter aircraft from Saab for use by the Brazilian Air Force, much of the recent contracts have pertained to the purchase of vessels intended to modernize the Brazilian Navy. Brazil’s five Type 209 diesel-electric attack submarines, acquired from Howaldtswerke-Deutsche Werft, will be joined by four Scorpène-class diesel-electric attack submarines to be built domestically with completion of the first vessel expected in 2017.

In March 2013, Brazil’s President Dilma Rousseff inaugurated a domestic shipyard at which Brazil’s first nuclear-powered submarine – the fittingly named BNS Alvaro Alberto – will be built with French support. Delivery of the completed vessel is not expected until 2025 but the success of the project would bring Brazil into a very small club of countries with operational nuclear-powered submarines: the United States, United Kingdom, France, Russia, India, and China.

The Barroso-class corvette commissioned in late 2008 also seems to have inspired a new series of ships for the Brazilian Navy. The domestic shipbuilder Arsenal de Marinha do Rio de Janeiro has been contracted to build four vessels based on the design of the Barroso-class but with “stealth capabilities” and which will possess both anti-ship and anti-air armaments. Delivery of the first of these new stealth corvettes is expected in 2019 and as such many specific details about the design are currently unknown. Furthermore, delivery of two new Macaé-class offshore patrol vessels is expected in 2015, while an additional two will be delivered in 2016-2017, bringing Brazil’s fleet of these patrol vessels to seven in total.

But why is there this rapid buildup in maritime forces for Brazil? To some degree, these new procurement projects are intended to offset the Brazilian Navy’s diminished capabilities following the retirement of 21 vessels between 1996 and 2005. This would not explain the focus on vessels with longer-range expeditionary capabilities, though. Some observers may attribute the acquisition of ships with capabilities clearly not intended for the patrol of inland waterways, such as the new “stealth-capable” Barroso-class corvettes, to the threat posed by Guinea-Bissau’s instability. That Lusophone West African country, which has been dubbed a “narco-state”, has been a major hub in the international drug trade; Colombian cocaine often makes its way to Guinea-Bissau from the Brazilian coast, only to then be exported onward to Europe. But President José Mário Vaz, who was elected by a decisive margin to lead Guinea-Bissau in May 2014, has quickly moved to crackdown on corruption in the Bissau-Guinean military and seems set to make counter-trafficking a priority during his term in office. Even if Brazilian policymakers believe it may be necessary to exert a stronger presence in the South Atlantic to discourage narcotics trafficking, a nuclear-powered attack submarine is not at all the right tool for the task.

Rather, it seems most likely that there are two principal factors motivating Brazil’s naval procurement projects. With regard to BNS Alvaro Alberto and the potential acquisition of a second aircraft carrier, Brazil craves the prestige of at least appearing to be the leading maritime power in the Southern Hemisphere. Participation in major international maritime exercises, such as the IBSAMAR series conducted jointly with Indian and South African forces, are intended to promote a view of Brazil as a power that ought to be respected and consulted, particularly as Brazilian policymakers continue to pursue a permanent seat for their country on the United Nations Security Council. More importantly, however, the shipbuilding projects on which Brazil has embarked are intended to build up domestic industry and contribute to economic growth.

Brazil is already attracting considerable interest as a shipbuilder. In September 2014, the Angolan Navy placed an order for seven Macaé-class offshore patrol vessels, with four to be built at Brazilian shipyards. Over the past several years, Brazil has exported various vessels and equipment for use by the Namibian Navy. Equatorial Guinea has expressed its intent to acquire a Barroso-class corvette from Brazil for counter-piracy purposes. The A-29 Super Tucano, a turboprop aircraft intended for close air support and aerial reconnaissance, is produced by Brazilian manufacturer Embraer and has been exported for use in roughly a dozen national air forces. If Brazilian industry is successful in producing submarines and stealth corvettes, demand for Brazilian military hardware will only grow, generating impressive revenue and creating many jobs.

Of concern, however, are Brazil’s long-term intentions with regard to the construction of BNS Alvaro Alberto. There are few navies in the world with the infrastructure and know-how necessary to successfully operate one or more aircraft carriers; after all, the club of those countries with aircraft carriers in service is limited to just nine. But the export of nuclear-powered attack submarines would undermine the international community’s non-proliferation treaty and could potentially harm international peace and stability. The Islamic Republic of Iran has been rumored to occasionally entertain plans to obtain a nuclear-powered submarine, while the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea has allegedly expressed a private interest in obtaining Soviet-era nuclear-powered submarines from the Russian Federation. This is not to say that Brazilian authorities would consider exporting such vessels to Iran, North Korea or other such regimes, but there is certainly a market for future submarines modelled on BNS Alvaro Alberto. It will be necessary to keep a very close eye on the Brazilian shipbuilding and nuclear industries in the 2030s, especially as domestic demand for this class of vessel is satisfied.

To obtain a deeper understanding of Brazil’s long-term strategic goals and to perhaps exert some degree of influence over Brazilian arms exports, it would be advisable for NATO to seek a partnership with the country. In August 2013, a partnership was established between NATO and Colombia, demonstrating that the Alliance certainly is interested in security affairs in the South Atlantic. Brazil could also contribute much know-how to NATO members, especially as the Alliance attempts to find its place post-Afghanistan. Clearly, there is much work to be done in the area of trust-building if such a partnership is to be found prior to the expected completion of BNS Alvaro Alberto: as Colombian officials visited with NATO counterparts to discuss the partnership, Brazilian policymakers were among those Latin American figures who condemned Colombia for the initiative.

Partnering with Brazil will be very challenging diplomatically, but it is an effort that must be made. This rising power will soon find itself with a blue-water navy and, as such, military vessels flying the Brazilian ensign will become an increasingly frequent sight in the South Atlantic.

Paul Pryce is a Junior Research Fellow at the Atlantic Council of Canada. This article can be found in its original form at Offiziere.ch.

Natalie Sambhi

Natalie Sambhi