China’s Defense & Foreign Policy Week

By David Scott

Chinese maritime strategy for the Indian Ocean reflects a couple of simple inter-related planks; espousal of a “two ocean” navy and espousal of the Maritime Silk Road. 2017 has witnessed important consolidation of each maritime plank. Each plank can be looked at in turn.

“Two Ocean” Navy

In expanding naval operations from the South China Sea and Western Pacific into the Indian Ocean, China is pursuing a “two-ocean” (战略, liang ge haiyang) strategy. This is the manifestation of China’s new strategy of “far-seas operations” (远海作战, yuanhai zuozhan) endorsed since the mid-2000s, to be achieved through deployment and berthing facilities across the Indo-Pacific, in part to meet energy security imperatives and thereby achieve “far seas protection” (远海护卫, yuanhai huwei) and power projection by the Chinese Navy. This shift from “near sea” to “far sea” is the decisive transformation in Chinese maritime thinking; “China’s naval force posturing stems from a doctrinal shift to ocean-centric strategic thinking and is indicative of the larger game plan of having a permanent naval presence in the Indian Ocean.”1 This naval force posture has brought Chinese naval operations into the eastern and then western quadrants of the Indian Ocean on an unprecedented scale in 2017.

In the eastern quadrant of the Indian Ocean, February 2017 witnessed the Chinese cruise missile destroyers Haikou and Changsha conducting live-fire anti-piracy and combat drills to test combat readiness. Rising numbers of Chinese surface ship and submarine sightings in the eastern quadrant of the Indian Ocean were particularly picked up in India during summer, a sensitive period of land confrontation at Doklam – e.g. Times of India, ‘Amid Border stand-off, Chinese ships on the prowl in Indian Ocean,’ July 4; Hindustan Times, ‘From submarines to warships: How Chinese navy is expanding its footprint in Indian Ocean’, July 5. This Chinese presence included Chinese surveillance vessels dispatched to monitor the trilateral Malabar exercise being carried out in the Bay of Bengal between the Indian, U.S., and Japanese navies, which represents a degree of tacit maritime balancing against China. Chinese rationale was expressed earlier in August by the Deputy Chief of General Office of China’s South Sea Fleet, Capt. Liang Tianjun, who said that “China and India can make joint contributions to the safety and security of the Indian Ocean,” but that China would also not “be obstructed by other countries.” India is increasingly sensitive to this presence (Times of India, ‘Chinese navy eyes Indian Ocean as part of PLAs plan to extend its reach,’ 11 August) in what India considers to be its own strategic backyard and to a degree India’s ocean for it to be accorded pre-eminence. In contrast, China’s growing maritime presence in the Indian Ocean lends maritime encirclement to match land encirclement of India.

In the western quadrant of the Indian Ocean, another first for Chinese deployment capability was in August when a Chinese naval formation consisting of the destroyer Changchun, guided-missile frigate Jingzhou, and the supply vessel Chaohu conducted a live-fire drill in the waters of the western Indian Ocean. The reason given for the unprecedented live fire drill was to test carrying out strikes against “enemy” (Xinhua, August 25) surface ships. The “enemy” was not specified, but the obvious rival in sight was the Indian Navy, which was why the South China Morning Post (August 26) suggested the drill as “a warning shot to India.” Elsewhere in the Chinese state media, Indian concerns were brushed off (Global Times, ‘India should get used to China’s military drills,’ August 27). Finally in a further development of Chinese power projection, in September a “logistics facility” (a de facto naval base) for China was opened up at Djibouti in September, complete with military exercises carried out by Chinese marines.

The Maritime Silk Road

At the 19th Party Congress held in October 2017, the Congress formally wrote into the Party Constitution the need to “pursue the Belt and Road Initiative.” The “Road” refers to the Maritime Silk Road (MSR) initiative pushed by China since 2013, with the “Belt” referring to the overland land route across Eurasia. The MSR is a maritime project of the first order, involving geo-economic and geopolitical outcomes in which Chinese maritime interests and power considerations are significant. May 2017 saw the high-level Belt and Road Forum held in Beijing, focusing on the maritime and overland Silk Road projects. A swath of 11 Indian Ocean countries participating in the MSR were officially represented, including Australia, Bangladesh, Indonesia (President), Iran, Kenya (President), Malaysia (Prime Minister), the Maldives, Myanmar, Pakistan (Prime Minister), Singapore, and Sri Lanka (Prime Minister).

On 20 June 2017, China unveiled a White Paper entitled Vision for Maritime Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative. This vision document was prepared by China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the State Oceanic Administration (SOA). It was classic win-win “pragmatic cooperation” involving “shelving differences and building consensus. We call for efforts to uphold the existing international ocean order.” This ignored China’s refusal to allow UNCLOS tribunal adjudication over its claims in the South China Sea.

The MSR presents a vision of interlinked ports and nodal points going across the Indian Ocean. The significance of the MSR is that China can expect to be involved in a three-fold fashion. Firstly in infrastructure projects involved in building up the nodal points along these waters that was alluded to in the Vision document by its open aim to “promote the participation of Chinese enterprises in such endeavors” and which could “involve mutual assistance in law enforcement.” Secondly, Chinese merchant shipping is growing greater in numbers, and thirdly, deploying naval power to underpin these commercial interests and shipping.

This pinpointing of ports across the Indian Ocean reproduces the geographical pattern of the so-called String of Pearls framework earlier mooted in 2005 by U.S. analysts as Chinese strategy to establish bases and facilities across the Indian Ocean – a chain going from Sittwe, Chittagong, Hambantota, and Gwadar. China of course consistently denied such a policy, but its drive during the last decade has been to establish a series of port use agreements across the Indian Ocean, now including infrastructure and facilities agreements at Mombassa and Djibouti.

Chinese penetration of ports around the Indian Ocean rim gathered pace during 2017. September saw Myanmar agreeing to a 70 percent stake for the China International Trust Investment Corporation (CITIC) in running the deep water port of Kyauk Pyu. The port is the entry point for the China-Myanmar oil and gas pipeline. CITIC is a state-owned company, and so represents deliberate central government strategy by China. In July Sri Lanka agreed to a similar 70 percent stake for the China Merchant Port Holdings (CMPH) in the Chinese-built port of Hambantota on a 99-year lease. CMPH is another state-owned company, and so again represents deliberate central government strategy by China.

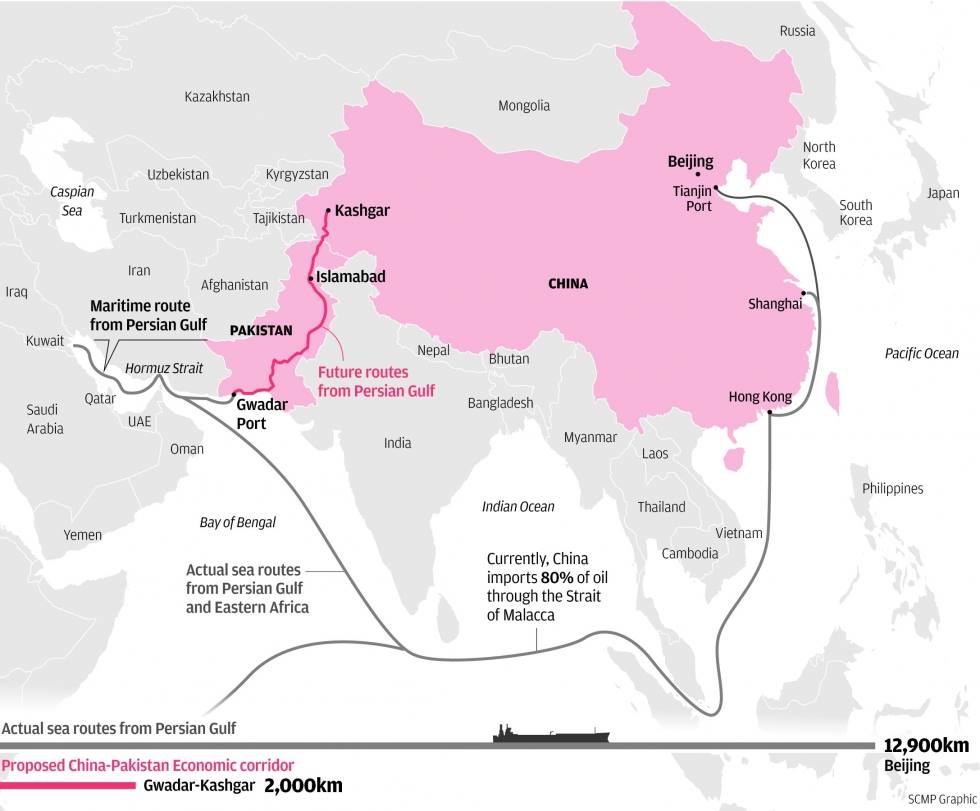

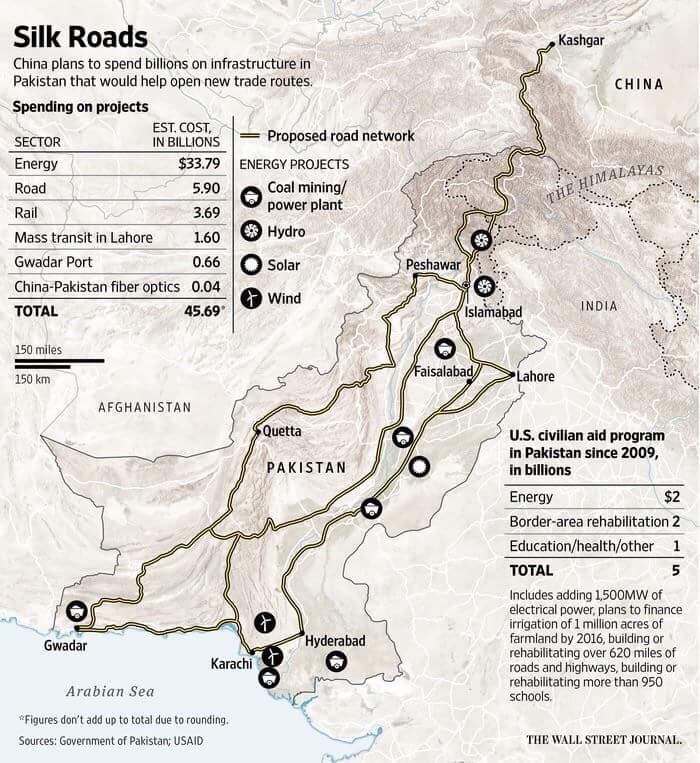

Gwadar, nestled on the Pakistan coast facing the Arabian Sea, has been a particularly useful “pearl” for China. Built with Chinese finance, it was significant that its management was taken over by the China Overseas Port Holding Company (COPHC) for a 40 year period in April 2017. This is deliberate strategy on the part of the Chinese government, given that COPHC is another state-run entity. The Chinese Navy has started using Gwadar as a regular berthing facility, in effect a naval base established for the next 40 years. Gwadar is also strategically significant for China given its role as the link between maritime trade (i.e. energy supplies from the Middle East) and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor which is set to improve infrastructure links between Pakistan and China.

From a strategic point of view, China’s use (and control?) of Gwadar and Kyauk Pyu will enable China to address its present vulnerability, the so-called Malacca Dilemma, whereby Chinese energy imports coming across the eastern Indian Ocean into the Strait of Malacca, could be cut either by the U.S. Navy or the Indian Navy.

It is significant that although India has been invited to join the Maritime Silk Road (MSR) initiative, India has avoided participation. Its absence at the Belt and Road Forum held in Beijing in May 2017 was conspicuous. The official explanation for this Indian boycott was China’s linking of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (which goes through Kashmir, a province in dispute between India and Pakistan) to the MSR initiative. In practice, India is extremely wary of the whole MSR initiative. Geographically, the MSR initiative surrounds India, and geopolitically Indian perception tends to be that it is but another Chinese way to encircle India. China of course denies any such encirclement strategy, but then it would deny such a policy anyhow.

The geo-economics of the Maritime Silk Road present China with interests to gain, maintain, and defend if need be. How can China defend such interests? Ultimately, through the Chinese Navy.

A More Powerful Navy

Chinese maritime strategy (a “two ocean” navy) is not likely to change, what will change is China’s ability to deploy more powerful assets into the Indian Ocean. This was evident at the 19th Party Congress. The formal Resolution approving Xi Jinping’s Report of the 18th Central Committee included his call to “build a powerful and modernized […] navy.” 2017 has seen Chinese naval capabilities accelerating in various first-time events.

One indicator of capability advancement was the unveiling in June at Shanghai of the Type 055 destroyer, the Chinese Navy’s first 10,000-ton domestically designed and domestically-built surface combatant. The Chinese official state media (Xinhua, June 28) considered this “a milestone in improving the nation’s Navy armament system and building a strong and modern Navy.” The Type 055 is the first of China’s new generation destroyers. It is equipped with China’s latest mission systems and a dual-band radar system.

So far aircraft carrier power has not been deployed by China into the Indian Ocean. China has converted one ex-Soviet carrier, the Varyag and inducted it into the navy in 2012 as the Liaoning. But China is already deploying “toward” the Indian Ocean where in January 2017 the Liaoning led a warship flotilla into the South China Sea, including drills with advanced J-15 aircraft. This was the first Chinese aircraft carrier deployment into the South China Sea, and constituted a clear policy to project maritime power. This projection was partly in terms of demonstrating clear superiority over local rival claimants in the South China Sea, and partly to begin matching U.S. aircraft carrier deployments into waters that China claims as its own, but which the U.S. claims as international waters in which it could undertake Freedom of Navigation Exercises.

A crucial development for China’s aircraft carrier power projection capability is the acceleration during 2017 of China’s own indigenous construction of aircraft carriers. This will deliver modern large aircraft carrier capability, and enable ongoing deployment into the Indian Ocean. China’s first home-grown aircraft carrier Type 001A, probably to be named the Shandong, was launched in April 2017 at Shanghai, with mooring exercises carried out in October at Dalian. Consequently, this new aircraft carrier is likely to join the Chinese Navy by late 2018, up to two years earlier than initially expected, and is expected to feature an electromagnetic launch system. It is expected to be stationed with the South China Sea Fleet, thereby earmarked for regular deployment into the South China Sea and Indian Ocean. This marks a key acceleration of China’s effort to build up a blue-water navy to secure the country’s key maritime trade routes and to challenge the U.S.’s dominant position in the Asia-Pacific region, especially in the South China Sea as well as India’s position in the Indian Ocean.

Countervailing Responses

The very success of China’s Indian Ocean strategy has created countervailing moves. In reaction to China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative, India has pushed its own Mausam and Cotton Route projects for Indian Ocean cooperation, neither of which involve China; and alongside Japan has also started espousing the Africa-Asia Growth Corridor (AAGC), which again does not involve China. U.S. espousal of the Indo-Pacific Economic Corridor (IPEC) connecting South Asia to Southeast Asia is also being linked up to the Indian and Japanese proposals. With regard to China’s “two-ocean” naval strategy, the more it has deployed into the Indian Ocean, the more India has moved towards trilateral security cooperation with the U.S. and Japan. Australia beckons as well in this regional reaction to China, as witnessed in the revival of “Quad” discussions between Australian, Indian, Japanese, and U.S. officials in 12 November 2017. This countervailing security development includes trilateral MALABAR exercises between the Indian, Japanese, and U.S. navies, in which their exercises in the Bay of Bengal in July 2017 showed a move of venues (and focus of concern about China) from the Western Pacific into the Indian Ocean, and with Australia likely to join the MALABAR format within this “Quad” development. China has become a victim of its own maritime success in the Indian Ocean, thereby illustrating the axiom that “To every action there is an equal and opposed reaction” – which points to tacit balancing in other words.

David Scott is an independent analyst on Indo-Pacific international relations and maritime geopolitics, a prolific writer and a regular ongoing presenter at the NATO Defence College in Rome since 2006 and the Baltic Defence College in Tallinn since 2017. He can be contacted at davidscott366@outlook.com.

References

1. Kupakar, “China’s naval base(s) in the Indian Ocean—signs of a maritime Grand Strategy?,” Journal of Strategic Anaysis, 41.3, 2017

Featured Image: Pakistan’s Chief of the Naval Staff Admiral Zakaullah visits Chinese ship on visit to Pakistan for participating in Multinational Exercise AMAN-17 in Karachi, Pakistan, on Feb. 12, 2017. (China.org.cn)

influence of emerging naval platforms and technologies in the geostrategic contours of the Indo-Pacific region. It identifies relevant historical precedents, forming the basis for various maritime development and security related projects in the region.

influence of emerging naval platforms and technologies in the geostrategic contours of the Indo-Pacific region. It identifies relevant historical precedents, forming the basis for various maritime development and security related projects in the region.