Chokepoints and Littorals Topic Week

By Elizabeth White

The Gate of Tears

Many a discussion of the Bab Al Mandeb Strait starts with the translation from the Arabic name (Gate of Tears) as an introduction to the chokepoint’s woes. They are not wrong to do so. The Gate of Tears seems to be a place of permanent melancholy, surrounded by a depressing miasma of conflict, state failure, famine, crime, and now global pandemic. Unfortunately for all concerned, it is also the key trading route between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean.

Pre-COVID-19, the Bab Al Mandeb saw the movement of some 6.2 million barrels per day of crude oil, condensate, and refined petroleum products. As well as oil, the two-mile-wide shipping lanes of the BAM also squeeze in local and international merchant shipping, military vessels, fishing trawlers, and cruise ships. The world cannot afford for the fourth busiest waterway to crumble into lawlessness and cripple a trade system and regional economy already teetering on the edge. Securing this chokepoint is vital to the U.S. and its allies, but they are not the only ones seeking to gain the upper hand in this turbulent patch of ocean.

The challenge of the BAM is not just the volume of merchant and military traffic squeezing through narrow channels. It is also bordered by weaker countries too focused on internal issues to lead collective security. The region is now also grappling with COVID-19 and its effects on every aspect of society, including maritime security. Already in 2020 the BAM has seen a sharp increase in piracy that is almost certainly linked to the pandemic sapping regional attention and resources.

Meanwhile, the existing tangle of competing interests continues to play out. Saudi Arabia’s seemingly intractable conflict with the Iran-backed Houthis in Yemen continues, occasionally spilling out into the Red Sea. China’s first overseas base in Djibouti appears to be under expansion, no doubt to the consternation of the U.S., France, and Japan, each with their own bases in Djibouti. Turkey is quietly building its presence in Yemen, with the backing of both Qatar and Oman. Egypt was already suffering economic woes from the disappointingly low uptake of the expanded Suez Canal. It is now also beset by COVID-19 hammering world trade, and Russia attempting to lure shipping to the alternative Arctic route. With all these complex moving parts, and the increasing desperation of some actors, the risk of a dangerous miscalculation is high.

Somebody needs to guard the gates. With global attention focused on COVID-19 and the security of the BAM increasingly fragile, is now the time to seize the initiative and establish hegemony or collective security in the Red Sea? Some actors may think so. But what would this take, what would it look like, and above all who is going to lead? These are questions that have global repercussions, and the actions of key players such as the U.S. and China could shape global trade for years to come.

Potential Guardians

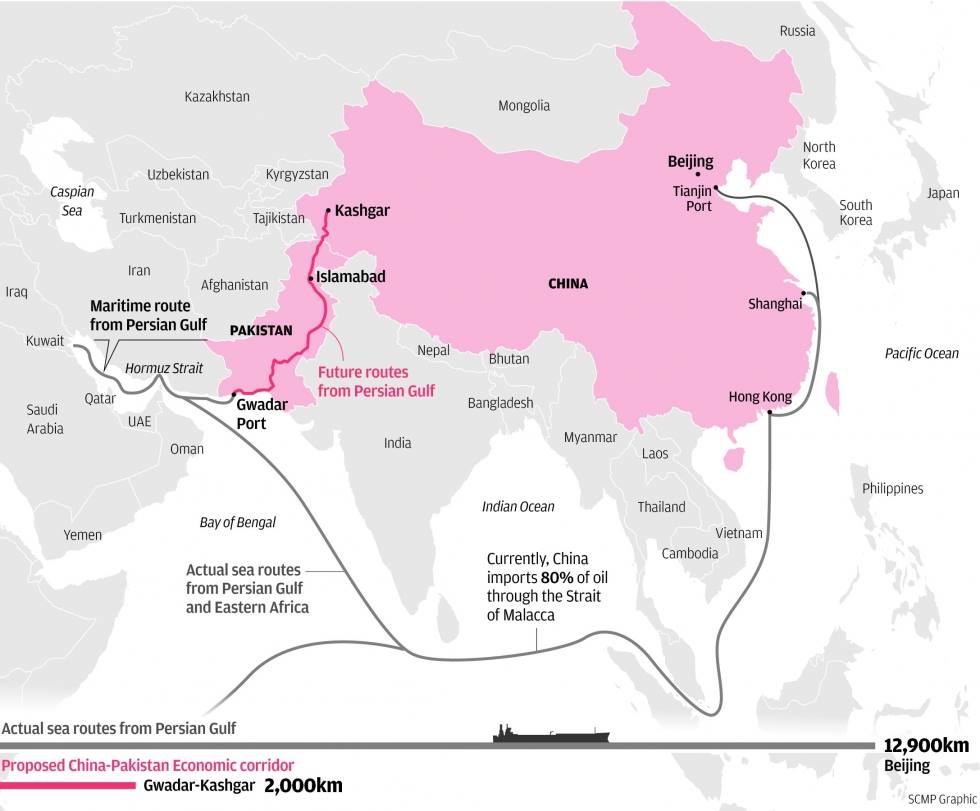

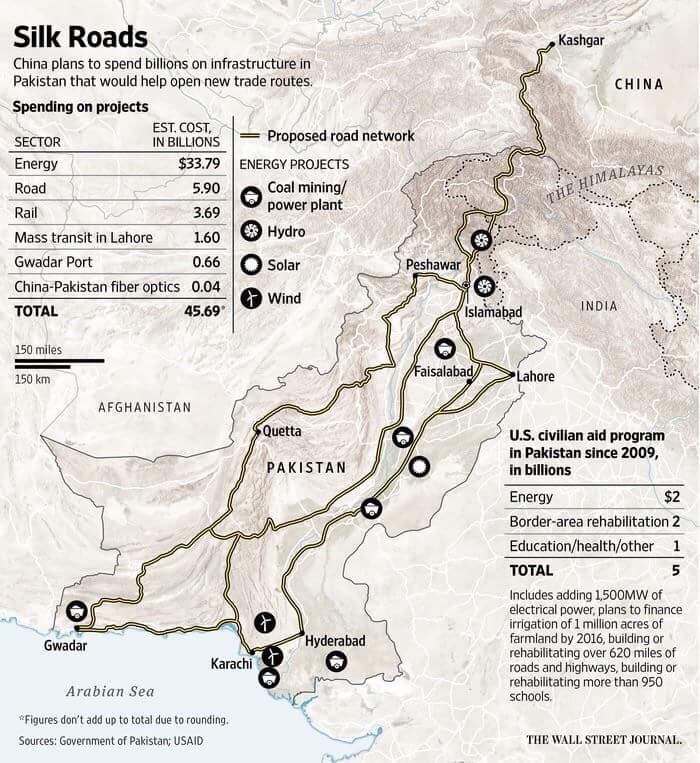

The BAM is only one of three key maritime chokepoints crowded into the Middle East, alongside the Suez Canal and the Straits of Hormuz. The Straits of Hormuz, the chokepoint for nearly all of the Middle East’s oil, is a high priority for many Asian countries in particular. Oil and petroleum products from the Persian Gulf will head east out of the Straits for Asian markets, with no need to head toward the BAM or the Red Sea. And yet, Djibouti is where China chose to place its first overseas base, ostensibly to support its operations to counter piracy in the Gulf of Aden. The move makes more sense when taken in the context of China’s Belt and Road Initiative and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (MSR). Since the announcement of the MSR by Xi Jinping in 2013, China’s investment in African infrastructure has been substantial as it eyes the mineral, oil, and other resource potential on the continent. While it plays the long game in Africa, building its economic and diplomatic investments, China still needs ready access to Middle Eastern oil and vital Indian Ocean trade routes.

All of this explains China’s interest in Djibouti, but what about the BAM itself? Even with its military presence now solidly established nearby, China is not yet getting involved in the rivalries and conflicts around the BAM. This is deliberate; China’s stance of neutrality means it can continue to cultivate its economic and diplomatic relationships in the Middle East and Africa without alienating one or more partners. Unless Chinese economic or strategic interests are severely threatened, it is doubtful it will take a more overt role in attempting to resolve the underlying causes of regional conflict around the BAM. Even if it were willing to do so, the People’s Liberation Army Navy does not have a history of playing well with others. It recently declined a similar opportunity in the Straits of Hormuz, and it is doubtful it would be able to lead its own coalition any time soon. Most countries are already committed to longstanding partnerships of their own that are not worth breaking for such a venture. If China wanted to secure the BAM via naval control, it would likely have to go it alone, a gargantuan effort with questionable returns.

One of the more plausible naval coalitions that could achieve control of the BAM would be the U.S.-led Combined Maritime Force (CMF). Although it technically already covers the BAM and the Red Sea, traditionally the CMF is more focused on the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Aden. Nevertheless, the CMF has the flexibility, skills, and credibility to take on a greater role in the BAM. But should it?

Say the CMF expanded its activities, secured access to land and littoral areas in Eritrea and Yemen, and actively patrolled the BAM, protecting from threats such as piracy, terrorist attack, or spillover from local conflicts. Depending on how muscular the approach was, such an act could backfire terribly. Fragile Yemen could splinter further, and the move could provide the green light to Houthis looking to aggressively assert their dominance in their own waters. Turkey may take advantage of the chaos to entrench itself further in the region, and while President Erdogan is experienced at working in a complex conflict zone, he is not known for his subtlety in combat. Saudi Arabia would potentially support the U.S., but that support could rapidly fade if it opened it up to further Yemeni attack at a time when it is trying to find a way to back out of its disastrous Yemeni campaign and still save face. Eritrea, Djibouti and other weaker regional states may not have the wherewithal to do much either way, but perceived threats to their sovereignty from U.S.-led military actions in the region could push them further into China’s arms.

Further Options

So what is the answer to securing the BAM? The activities that have worked in the past, such as the suppression of piracy off the Horn of Africa, relied on an overt international naval presence; a big grey ship on the horizon tended to result in a sudden change of plans by would-be pirates. Being able to point to tangible actions with a visible result makes naval intervention a tempting response to further issues around the BAM. Such actions will not be a panacea, nor will their effects last if the navies subsequently withdraw without continued regional capacity-building efforts. But that does not mean a strong naval presence by the U.S. and its partners is pointless. From its first major base beyond its own waters, China will be looking at the lessons learned in the Middle East Region about how Western forces react in volatile situations. Other actors will also be looking at how much of a role the U.S. and its partners take in the BAM, and adjusting their actions accordingly. And Iran does not need a further excuse to fuel regional instability, particularly with Qassem Soleimani no longer acting as a brake on some of the more exuberant parts of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps.

An increased – and increasingly visible – presence by the U.S. and its partners is warranted, leveraging existing partnerships and working with new and inexperienced partners. Activities such as passing exercises, boarding practice, and sailing in company help build regional capability and confidence (or at least keep some of the less professional navies out of trouble). A similar approach is used in the Persian Gulf via the CMF’s Combined Task Force (CTF) 152, but this does not necessarily make it a suitable blueprint. Led by local states for most of the past 10 years, CTF 152 is tasked with regional maritime cooperation between Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. The fairly straightforward tasks, focused on a mutual enemy (illicit non-state actors), provide a sandpit that regional countries can use to build trust and skills. But trying to get the countries of the Gulf to play together nicely is hard enough; expecting Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Eritrea, Djibouti, and Somalia to cooperate in providing regional maritime security (in the unlikely event they all had the resources to do so) is a fantasy.

Instead, a U.S. coalition should take the lead in a more overt naval presence. While China has pursued a carefully crafted and long-term military engagement in Africa (including sales of increasingly sophisticated military equipment), U.S. and like-minded military engagement with the countries surrounding the BAM has been patchy at best. But a stronger U.S.-led presence must be in the context of equally overt diplomatic and economic engagement that builds regional trust, not suspicion. It would be easy otherwise for such efforts to be misinterpreted as neo-colonialism. This risk can be countered, but it requires a concerted diplomatic effort and buy-in from regional states.

In counter-piracy this has come through activities such as the Shared Awareness and Deconfliction (SHADE) initiative and the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (ReCAAP). These could prove good models for coordinating and supporting naval activity focused on securing the BAM from a range of threats. Whatever takes place, any military activities in the BAM must use existing international norms and laws, reinforcing their validity and acceptance. To shun such norms only gives countries like China more incentive to disregard them elsewhere, such as in the South China Sea, and to continue a dangerous influx of high-tech weaponry in an already volatile region.

Conclusion

The security situation in the BAM does not look like it will be resolved any time soon; indeed, with the multiplying effects of pandemic, economic collapse and plunging oil prices, it is likely to get worse. International naval control of the BAM is possible, but only in coordination with regional states, with diplomatic and economic investment, and respect for international maritime law. Balancing these moving parts will take determination; but the rewards of shaping and influencing the regional approach to the BAM for years to come make it a price that may well be worth paying.

Elizabeth White is a former Australian Defense official. The opinions expressed here are her own.

Featured Image: On May 26, 2002, the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) captured this image of sun glint in the Red Sea, between Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. (Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Land Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC)

influence of emerging naval platforms and technologies in the geostrategic contours of the Indo-Pacific region. It identifies relevant historical precedents, forming the basis for various maritime development and security related projects in the region.

influence of emerging naval platforms and technologies in the geostrategic contours of the Indo-Pacific region. It identifies relevant historical precedents, forming the basis for various maritime development and security related projects in the region.