Guest article by Brian Scopa, USN.

“Once is happenstance. Twice is coincidence. Three times, it’s enemy action.”

-Ian Fleming

M looking for W? W looking for M? PRC looking for Intel?

The revelation that the Office of Personnel Management has been hacked, allegedly by the Chinese, has profound implications for the safeguarding of classified US information. Beyond the typical identity theft problems associated with any breach of Personally Identifiable Information (PII) from a government or private database, the fact that the data on 4.1 million military and government personnel contained information on their security clearances is extremely grave. This is not only an egregious breach of individual privacy, but when combined with two other hacks of private websites make for a counterintelligence nightmare.

Allowing ourselves to go briefly down the conspiracy theory rabbit hole, two additional hacks of private websites are worth considering in conjunction with the OPM hack:

“LinkedIn Security professionals suspected that the business-focused social network LinkedIn suffered a major breach of its password database. Recently, a file containing 6.5 million unique hashed passwords appeared in an online forum based in Russia. More than 200,000 of these passwords have reportedly been cracked so far.”

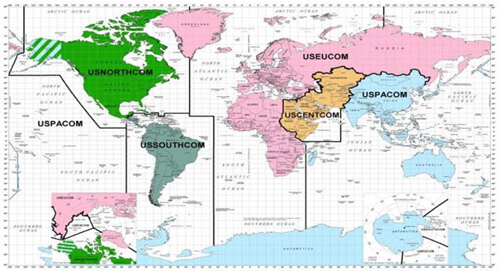

The consensual aggregation of personal and employment information online has greatly simplified the task of finding targets for intelligence gathering. The technology that makes finding a project manager with an MBA and five years of experience fast and convenient also makes it easy to track down missile and radar engineers on LinkedIn. The publicly available information on LinkedIn is a trove of intelligence in itself regarding military, government, and contract employees that work in defense related industries. Having the private email addresses and passwords of LinkedIn members has staggering spearfishing implications ala STUXNET.

Adult Friend Finder (AFF) in May 2015

“Andrew Auernheimer, a controversial computer hacker who looked through the files, used Twitter to publicly identify Adult FriendFinder customers, including a Washington police academy commander, an FAA employee, a California state tax worker and a naval intelligence officer who supposedly tried to cheat on his wife.” (emphasis mine)

Catching Flies

Developing intelligence sources costs time, money, and effort, regardless of the method employed, and intelligence agencies are constantly searching for ways to more efficiently target and recruit intelligence sources. The OPM and LinkedIn hack simplify the targeting, but it’s the AFF hack that helps with recruitment.

One of the most useful tools intelligence agencies have for recruiting sources is blackmail, and a ‘Honey Trap’ is the practice of luring a potential intelligence source into a compromising position with a romantic partner that’s working for an intelligence agency, and either gaining their cooperation in the name of love, or blackmailing the source into compliance.

The Chinese are apparently particularly fond of this specific type of intelligence gathering operation:

“MI5 is worried about sex. In a 14-page document distributed last year to hundreds of British banks, businesses, and financial institutions, titled “The Threat from Chinese Espionage,” the famed British security service described a wide-ranging Chinese effort to blackmail Western businesspeople over sexual relationships.”

The AFF hack is probably the first Massive Multiplayer Online Honey Trap (MMOHT). Even better for foreign intelligence agencies (FIAs), it was self-baiting and required zero investment of resources.

How bad is it?

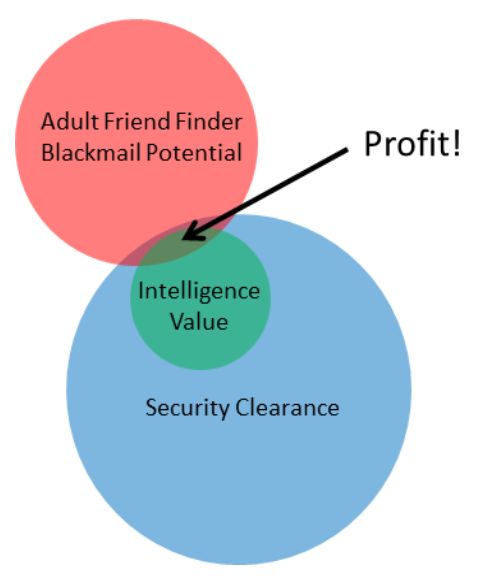

Perverting the Drake Equation for this exercise, we can conduct a thought experiment about the number of potential intelligence sources created by the confluence of the three hacks mentioned above, expressed mathematically as P = O * W * N * Y, where:

P = Total number of useful possible US government employee intelligence sources that could be exploited.

O = All government employees with security clearances whose personally identifiable information has been compromised, reported to be 4.1 million.

W = Fraction of O that are AFF members. This number has not been made public by the DoD, if it’s known, but the reported number of member profiles compromised was 3.5 million.

N = Fraction of W that desperately want their activities on AFF to remain undisclosed and could be effectively blackmailed. Not everyone will be embarrassed by their activities on AFF.

Y = Fraction of O that has been or is currently employed in a position that a FIA would find useful to turn into a source of intelligence.

Since I don’t have any insight into the any of the variables with the exception of O, I won’t speculate on what P might be, but I have no doubt that it’s an actionable, non-zero number that FIAs must be rushing to exploit.

Lessons Re-identified, Still Unlearned

Any information that’s online can be accessed online- full stop. We should all assume that any device connected to the public internet is hackable, and act accordingly. While there are many good precautions and security features that individuals, companies, institutions, and governments can take to better protect online dealings and information, such as two-factor authentication, tokens, and salted password hashing, it has been demonstrated time and again that the advantage in the cyber security arms race is with the attacker. You cannot count on technical means alone to protect your information. If individuals with security clearances have used the internet to facilitate behavior that the knowledge of by a third party could lead to blackmail, the individuals should assume the information will be made public.

Security through obscurity is always a loser, but anonymity is still worthwhile. The critical information that makes blackmail possible in this instance is being able to identify government employees that were also members of AFF. If AFF members had taken care to remain anonymous by making their member profiles non-attributional, using email addresses and phone numbers not otherwise linked to them, using non-identifiable pictures, and keeping locations ambiguous, they may yet have some measure of protection from identification.

What’s next?

This is only the beginning of this particular saga. In the coming months I have no doubt we’ll hear about the hacks of other popular dating, hook-up, and porn sites. The hacking itself has probably already happened; it’ll just take time for the discoveries to be made.

The news is grim, but there is opportunity here. While FIA see openings, our own counterintelligence organizations have an unprecedented opportunity to identify potential targets before they can be contacted by FIAs and possibly prepare them to act as double-agents, turning the honey traps on the attackers. If nothing else, the act of sharing the blackmail information with the security services helps to inoculate the individuals against blackmail, since it’s typically (but not always) the fear of disclosure that makes the information useful, not the specific behavior that’s problematic.

In any case, it’s time for a DoD-wide effort to review the list of AFF members and check it against current and past employees with security clearances. Then, command security officers can start having the difficult, closed-door conversations necessary to learn the scope of the possible vulnerability. Doing so will limit the damage from this hack, and it’ll be a useful exercise in preparing for the next episode.

Which has already happened.