By Mie Augier and Major Sean F. X. Barrett

This is the first of what we hope will be several conversations with General Anthony Zinni, USMC (ret.) about leadership, strategy, learning, and the art and science of warfighting. General Anthony Zinni served 39 years as a U.S. Marine and retired as Commander–in–Chief, U.S. Central Command, in 2000.

In this installment, General Zinni discusses themes in his “Combat Concepts” lecture, his recently completed doctoral dissertation, his time at the CNO’s Strategic Studies Group, and the state of strategic thinking.

Were you influenced by any particular interests, books, or mentors?

Zinni: First, on people, General Al Gray was probably the biggest influence on me. I’ve known him since I was a captain. He had a set of people. He mentored us and sought us out all the time. He was unusual to us junior officers. He was willing to talk about things we were interested in—tactics, leadership, and those kinds of things. It was hard to find senior officers who really had that kind of connection. Plus, his personality was such that he drew people to him. He seemed to understand what we were going through, what we were thinking. You must remember we had come back from a couple of tours in Vietnam, so our first decade in the Marine Corps was formed by Vietnam. Of course, he was there, too—more senior, but he really understood what we saw and our reaction it.

Lieutenant General Mick Trainor was my battalion commander. He had a reputation in the Marine Corps for being a highly intelligent officer, and he was someone who really understood warfare, especially in Vietnam. He was another mentor—I have had several, most of them later made general officer—so I was a pretty good chooser of mentors [laughs].

In terms of books, I read a lot, but I don’t have a particular way of listing them. I talk with Lieutenant General Paul K. Van Riper about this a lot. He really focuses on specific books, and I don’t. I read a lot of books. I always get taken aback when junior officers ask me, “Can you give me a reading list or a list of recommended books?” I say, “You should read all the books you can get ahold of, and then sort out what you think are the important books.” Usually, they get onto doing that. But it’s also a lazy way of saying, ‘I don’t always remember what I’ve read in all these books’—I gather it in and hopefully integrate it.

One of the big themes in your well-known “Combat Concepts” talk is the need to extend maneuver thinking beyond warfighting concepts to application. For you, General Gray, and others, it seems this wasn’t a contrast. Maneuver warfare was a way of thinking and a practice at the same time.

Zinni: Yes, I would say it’s a way of thinking. It is more a way of how you form concepts about operational art. However, what I felt was lacking in some discussions was going to the next step—to application, to practice. People who didn’t want to take that step bothered me. Execution is just as hard as conceptualizing. John Boyd talked about that. He took the concepts and talked about applications. He was the maneuverist who tried to bring in some form of application. Of course, General Gray was that way, too. He was always interested in application. He asked us all the time, “How would you translate that into action, or into application?” He always wanted to take it to the next step, but it was rare to find people who thought conceptually like that—and then extra rare to find people who tried to translate it into application.

Regarding your experience in Vietnam, it seems like, for you and your peers, it was a very formative part of your career. It became critical for what drove you and others to embrace education, self-study, learning, and some more maverick ways of thinking since it was obvious the things we were doing needed to change. How can we foster that kind of maverick thinking in our organizations today? How well do you think we are doing?

Zinni: Well, from my experience, it must start at the top. You need license to be a maverick. That is how most effective change comes about. In my dissertation, I looked at our senior military leadership during World War II. If you look at George Marshall, Earnest King, or Hap Arnold, they were not necessarily mavericks, but they believed in the freedom to innovate. They believed in cultivating thinkers and mavericks that acted and thought differently. They protected the Nimitzs, the MacArthurs, and the Stillwells—all the guys in the Pacific at that time that I looked at. These were majorly flawed people. Nimitz ran a ship aground when he was a young officer! MacArthur had a checkered past, was not very well liked in the Army, and his actions in the Philippines were disastrous. Stillwell was a character nobody liked to be around. But Marshall and King saw in them what was needed for that war. They had rebel spirits. Marshall and King recognized the war would be different, so they sought out the innovators, the thinkers, and that sort of cascaded down.

The top leadership out in the theater began to move the traditionalist thinkers aside. They did not take an axe to, or fire, everyone. Rather, they moved them into positions where they couldn’t influence or affect the process of change. The first fleet commander at the Guadalcanal landing was an old school guy who didn’t get it, so Nimitz moved him out and brought in Halsey to lead the fleet. That basically saved the day at Guadalcanal.

You can go down this concept of innovate, test, adapt, and adopt. This goes all the way down the ranks to squadron officers figuring out new formations, new patterns to fly. It gets diffused in the organization where it breaks down resistance. It is not kept as something separate, which is a problem we have today and what causes most organizations to fail. Your whole organization must feel part of the team and involved in change. Isolating a special section of super innovators in an organization fails 95 percent of the time in the corporate world. Everybody resents them.

In your dissertation, you mention the importance of seeing things in a strategic or visionary way. Why has there been a decline in national-level strategy and strategic thinking?

Zinni: Well, I think there were flashes of strategic thinking of some quality, maybe with George Washington, but that was more operational. Then, I think the next time you see it is Grant as a commander. Lincoln knew he needed a strategy but didn’t know how to develop one until he found Grant. But that was a moment. The next time you see it is with Roosevelt because as soon as Pearl Harbor was attacked, he called in Marshall and said, “We need a strategy.” He started to give the principles of a strategy: we will become the arsenal of democracy. What that meant is we will go to our strengths, which was our industrial base, and we will out-produce the enemy. We were producing more tanks in a month than the Germans could produce in a year at the height of their industrial capability. In 3.5 years, we built 90 carriers. He also said we must get our act together with our allies. He went to the UK, formed the Combined Chiefs of Staff, and said it is Europe first. These are strategic principles.

Marshall, who thought and acted strategically, started putting these things together. On the Navy side, they were thinking strategically in terms of the Pacific, but in the Atlantic, it was more of a support role. Certainly, Hap Arnold and strategic bombing was also being thought about. You see strategy in wartime. The greatest time of U.S. strategic thinking came from 1944 to 1950. Truman was President; Marshall was Secretary of State and then Defense. You have people like Vandenberg who worked with them across political differences. If you look at that period, we were stabilizing the world economy, we created NATO, we passed the 1947 National Security Act. All these things were happening, and we were developing the ideas of deterrence. That carried us through the Cold War. There were moments when it lessened, like during the Vietnam War, where we had no strategy, and Korea was not much better. But the overall grand strategy was solid in terms of how we were dealing with the peer threat.

You began to see it wane, and when the Cold War ended, it totally ended our strategic thinking. When George H. W. Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev talked about a peace dividend and a new world order, every reporter asked them, “What does that mean? How do you build a new world order? What is this peace dividend?” They never provided an answer. Bush got so frustrated he said, “Oh, you mean the vision thing”—the vision being a key element to strategic thinking. One needs a vision, but he couldn’t be bothered by it. Subsequent presidents also dismissed it. Obama, for example, said something like, “I don’t need any Kennans,” when he got pressed by a reporter.

What the heck is your strategy if you don’t have a vision? We totally lost the ability at the senior leadership level in America to provide, at the very least, strategic principles and underpinnings. Instead, we went off and launched conflicts in places like Afghanistan and Iraq with no idea of what we were trying to do. I blame the uniformed military for a lot of this because it is their job to ask those questions. I had retired, and I was asked by a subsequent commander at CENTCOM to come to his headquarters and talk. I talked to him at length. He was frustrated. He said, “You know what, I don’t know what I am supposed to do. I have no idea what I am supposed to do.” He had a war going on in Afghanistan and Iraq, and he has no idea what the political objectives are, what the desired end state is, how it ends.

If a lack of national-level strategy makes it difficult for our organizations to do anything strategic, how do we get better at it again?

Zinni: That’s a key question, but it is hard to answer because we change administrations every four years. Even if a President gets eight years, his cabinet turns over at least once during his time, so there is no consistency. No one who comes into these offices goes through a strategy course before becoming Secretary of State or Secretary of Defense, or the National Security Advisor. What strategic education or training do they have? The problem is that in the military we build this tremendous planning and thinking construct, and the whole thing—as magnificent as it is—ultimately relies on plugging it into a strategy, a vision, an end state.

The only time I personally saw a moment of strategy was in the 1980s when we had fixed the military, if you will, with the all-volunteer force, and we began to test operational skills. That became a critical point to be promoted and be successful. The military decided to take on at least some of the upper end of operational art and strategy. You had the Maritime Strategy, AirLand Battle, Deep Battle—these at least were high-end, conceptual ways of doing business. I always told people I was at the bottom end of strategy as a combatant commander. I had to have a theater strategy, but I had no delusions that I was preparing grand strategy or anything like that. I was where strategy touched operational art.

I had to have a theater strategy, and I had to have a matching set of applications to go with it. I had no real guidance. I was basically on my own. I read everything that said “strategy” on the cover. My staff piled it up on tables in my office: content from all the other combatant commanders, the National Security Strategy, every country plan in my area of responsibility. I read all the DoD and State Department stuff. It was not very useful. First, very little of it said anything. Then, when you looked at it, even the terminology for the same things was different. Everybody made up his own, and there were so many inconsistencies in what was going on. There were no driving principles, no driving strategic goals and objectives. Nothing drove or directed our processes.

You know, Goldwater-Nichols, most people miss the part that says the President will provide a strategy within the first 150 days of his or her presidency. Then, every year it is to be updated, with the budget, and sent to Congress. I think Goldwater and Nichols tried to elevate the debate about how the resources being provided had to be based on strategic understanding and coherence between the providers in Congress and the executors in the Executive Branch. It never happens that way.

You were involved with the Navy Strategic Studies Group (SSG). How did you get involved with it, and would that be something we could reinvigorate to help nurture and educate strategic thinkers?

Zinni: You know, it started out that way, as a forum to do just that. My group may have been the last one that was truly doing a strategic study. The SSG was originally formed by the Chief of Naval Operations to take a strategic issue and spend a year studying it. Then, come back and answer the question the CNO wanted studied. This later deteriorated, maybe during the group after me, into doing studies on recruiting, manpower, things like that.

We had an interesting one. The Maritime Strategy had been on the street for a while, and the CNO wanted to know if it was getting any reaction from the Soviets. We spent the first half of the year delving into intelligence to see if the Soviet commanders responded to the Maritime Strategy. We spent the second half of the year determining whether they responded in a way that necessitated an update to the Maritime Strategy either to counter their reactions or take advantage of their reactions.

What was eye opening to me was interviewing a defector who was with the GRU. I was going over things we did operationally to see how the Soviets responded to it. He put up with this for an hour or two before he finally started laughing. I asked, “What’s so funny?” He said, “You are going about this the wrong way. Do you understand that you feed the Soviet Army?” Reagan had approved grain sales to Russia after their five-year plan failed and they had big food shortages. This was very controversial in the United States, but Reagan saw this as a benefit to our farmers. He got enough support in Congress to do this, but this guy was telling me, without that, the Soviet Army doesn’t eat! That made us think we might be going about this the wrong way. We were thinking in terms of kinetic exchange, battlefield stuff.

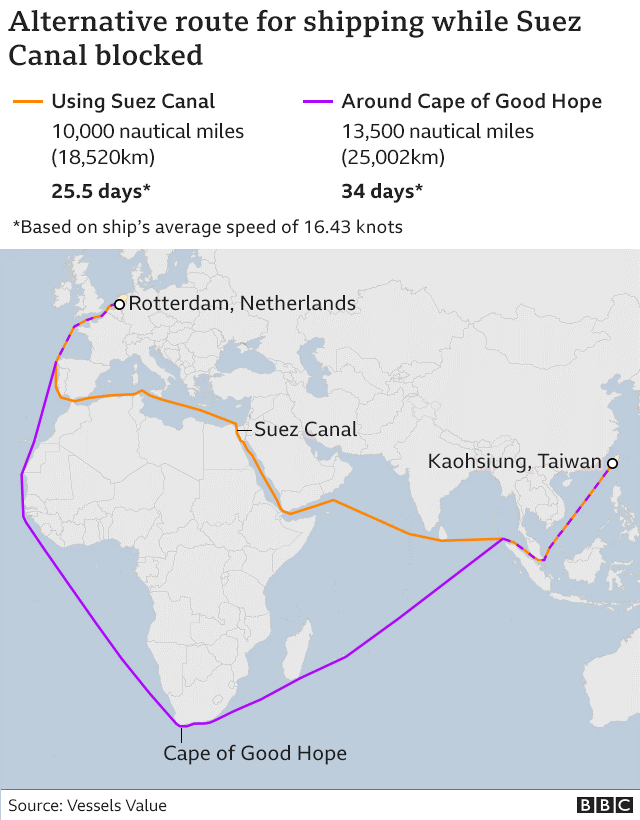

What if we cut off outside resources? How dependent is the Soviet Union on outside resources? We looked at dependencies—this was one, but also other dependencies on raw materials and food stuffs. Then we looked at a broader maritime strategy. We could blockade the Pacific ports of the Soviets. Cutting off supply and resupply of critical elements was of greater strategic advantage than what we were thinking about doing kinetically on their maritime flanks. These were the kinds of issues we were thinking of in the SSG.

We are just not very good at strategy anymore. Back when we had a decent approach to it, during Desert Storm/Desert Shield, we at least had some idea strategically. We did not want to make Iraq the 51st state; we didn’t want to own it. We wanted to stamp out Saddam, then go to containment, and do it in a way that we didn’t end up with a broken Iraq on our back. Brent Scowcroft understood the limits of the military there. He was an Air Force two-star, and you had James Baker as the Secretary of State, who was a former Marine officer, and also a decent strategic thinker. And, of course, you had Colin Powell as the Chairman, who had a lot of influence within the administration, above just being the Chairman.

They crafted the strategy to not go to Baghdad, and then the containment strategy after that, which we were able to define and refine down to just 23,000 troops, on any given day, containing Iraq. Less than the number reporting to the Pentagon every day. The effort was to avoid making those 23,000 waste their time, so we created live fire ranges out in Kuwait so they could get trained. We tried to create an environment with our allies for joint training that made the containment more than sitting around somewhere.

There was a flickering of some strategic thinking in there, but again, what you saw was a 4-star general, General Powell, who had a lot of influence in the government, and a National Security Adviser who was a retired Air Force general. They understood what the limitations were. But it was controversial. There were many politicians who thought we should have gone to Baghdad even though we would have been handed a mess, but at least back then, we had overwhelming force, which was a tenant of what Powell advocated. By overwhelming force, Powell didn’t just mean military force. He meant bringing in allies, making sure the international community is behind you, getting that UN resolution, because you want to have the overwhelming moral force, not just the military force. But they, and that kind of strategic thinking, got discarded and pushed aside.

Regarding the 1980s Maritime Strategy, what can we do now to get back to that kind of approach?

Zinni: I really think it is time to think about a Maritime Strategy, much the way we framed it back in the 80s. In the 80s, there were several motivations for doing it. We weren’t that far out from Vietnam. The concentration in the 70s was on rehabilitating the services from the effects of Vietnam, building the all-volunteer military, and creating more education opportunities in the military. When we hit the 80s, it opened up for the next step, which was sort of a renaissance, and we began looking at operational art.

You saw maneuver warfare, AirLand Battle, and the Maritime Strategy in the 80s. The Navy and Marine Corps came together and thought about a lot of questions pertaining to possible conflict with the Soviet Union, and people wanted to become more creative about how we would engage in such an operation. The Navy and Marine Corps said, “OK, how do we play in that? We are not central front forces. Is there a role on the flanks?” This opened and challenged thinking. Traditional thinking, for example, is you never take a carrier close into the shore. Well, we ended up proposing that carriers go into the fjords in Norway. We looked at seizing areas in the Mediterranean and the Baltic and then pressuring the flanks of any Soviet effort in the central region.

What we looked at in the SSG was very insightful because those were things we hadn’t thought about at the strategic level. The SSG, unfortunately, fell off. Its high-water mark was in the 80s. By the time the 90s came around, the SSG wasn’t doing anything strategic. They became an administrative analysis group, rather than a strategic thinking group. It lost its strategic nature, and with the collapse of the Soviet Union, we went into a pause in our strategic thinking overall.

How do we make sure we develop people who are asking the right questions and not falling victim to biases and projecting what we want to believe, or what we want to believe is happening in other countries?

Zinni: It’s a great question, and I go back to people like George Marshall, who had the same question. What Marshall did—and General Gray was like this, too—Marshall wanted to know who his senior leaders, mid-range leaders, and maybe even some of his junior leaders were. Marshall spent a lot of time talking with his leadership, trying to understand who they were. There were always rumors about Marshall having a little black book about the leaders he thought were the best or had something. People later realized he never really had a black book, but he had a black book in his mind.

When World War II started, he immediately knew who he had to move out and who he wanted to move in. The people he identified early on as promising were put in at the division, corps, and field Army levels, and they were remarkably good. He then started to form these groups where he encouraged them to come together afterhours to discuss the art of war, operational art, and the profession of arms. He wanted this dialogue to continue amongst these groups that he established. General Gray and Lieutenant General Trainor did the same thing. Within these groups, they could begin to see who the thinkers were.

You must not only go after the thinkers, however, but also those who can lead, execute, and apply. You must marry the two together. There is a place for people who can only do the conceptual, but you are really looking for the future leaders who can tie the conceptual to the application. Our senior leadership needs to do what Marshall did and try to personally discover these people and identify them, and not just believe the system can do it on its own.

Read Part Two here.

General Anthony Zinni served 39 years as a U.S. Marine and retired as Commander–in–Chief, U.S. Central Command, a position he held from August 1997 to September 2000. After retiring, General Zinni served as U.S. special envoy to Israel and the Palestinian Authority (2001-2003) and U.S. special envoy to Qatar (2017-2019). General Zinni has held numerous academic positions, including the Stanley Chair in Ethics at the Virginia Military Institute, the Nimitz Chair at the University of California, Berkeley, the Hofheimer Chair at the Joint Forces Staff College, the Sanford Distinguished Lecturer in Residence at Duke University, and the Harriman Professorship of Government at the Reves Center for International Studies at the College of William and Mary. General Zinni is the author of several books, including Before the First Shots Are Fired, Leading the Charge, The Battle for Peace, and Battle Ready. He has also had a distinguished business career, serving as Chairman of the Board at BAE Systems Inc., a member of the board and later executive vice president at DynCorp International, and President of International Operations for M.I.C. Industries, Inc.

Dr. Mie Augier is Professor in the Graduate School of Defense Management, and Defense Analysis Department, at NPS. She is a founding member of NWSI and is interested in strategy, organizations, leadership, innovation, and how to educate strategic thinkers and learning leaders.

Major Sean F. X. Barrett, PhD is a Marine intelligence officer currently serving as the Operations Officer for 1st Radio Battalion.

Featured Image: Sgt. William J. Puckett, an assault amphibious crew chief with Alpha Company, 2nd Assault Amphibian Battalion, 2nd Marine Division, watches from the turret of his AAV as Marines with his unit conduct a Gator Square after disembarking from the USS Whidbey Island off the coast of Camp Lejeune, N.C., Sept. 10, 2014. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Lance Cpl. Justin Updegraff / Released)