By Scott A. Humr

Winning on the future battlefield will undoubtedly require an organizational culture that promotes human trust in artificial intelligent systems. Research within and outside of the US military has already shown that organizational culture has an impact on technology acceptance, let alone, trust. However, Dawn Meyerriecks, Deputy Director for CIA technology development, remarked in a November 2020 report by the Congressional Research Service that senior leaders may be unwilling, “to accept AI-generated analysis.” The Deputy Director goes on to state that, “the defense establishment’s risk-averse culture may pose greater challenges to future competitiveness than the pace of adversary technology development.” More emphatically, Dr. Adam Grant, a Wharton professor and well-known author, called the Department of Defense’s culture, “a threat to national security.” In light of those remarks, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, General David H. Berger, stated at a gathering of the National Defense Industrial Association that, “The same way a squad leader trusts his or her Marine, they have to trust his or her machine.” The points of view in the aforementioned quotes raise an important question: Do Service cultures influence how its military personnel trust AI systems?

While much has been written about the need for explainable AI (XAI) and need for increasing trust between the operator and AI tools, the research literature is sparse on how military organizational culture influences the trust personnel place in AI imbued technologies. If culture holds sway over how service personnel may employ AI within a military context, culture then becomes an antecedent for developing trust and subsequent use of AI technologies. As the Marine Corps’s latest publication on competing states, “culture will have an impact on many aspects of competition, including decision making and how information is perceived.” If true, military personnel will view information provided by AI agents through the lens of their Service cultures as well.

Our naval culture must appropriately adapt to the changing realities of the new Cognitive Age. The Sea Services must therefore evolve their Service cultures to promote the types of behaviors and attitudes that fully leverage the benefits of these advanced applications. To compete effectively with AI technologies over the next decade, the Sea Services must first understand their organizational cultures, implement necessary cultural changes, and promote double-loop learning to support beneficial cultural adaptations.

Technology and Culture Nexus

Understanding the latest AI applications and naval culture requires an environment where experienced personnel and technologies are brought together through experimentation to better understand trust in AI systems. Fortunately, the Sea Service’s preeminent education and research institution, the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS), provides the perfect link between experienced educators and students who come together to advance future naval concepts. The large population of experienced mid-grade naval service officers at NPS provides an ideal place to help understand Sea Service culture while exploring the benefits and limitations of AI systems.

Not surprisingly, NPS student research has investigated trust in AI, technology acceptance, and culture. Previous NPS research has explored trust through interactive Machine Learning (iML) in virtual environments for understanding Navy cultural and individual barriers to technology adoption. These and other studies have brought important insights on the intersection of people and technologies.

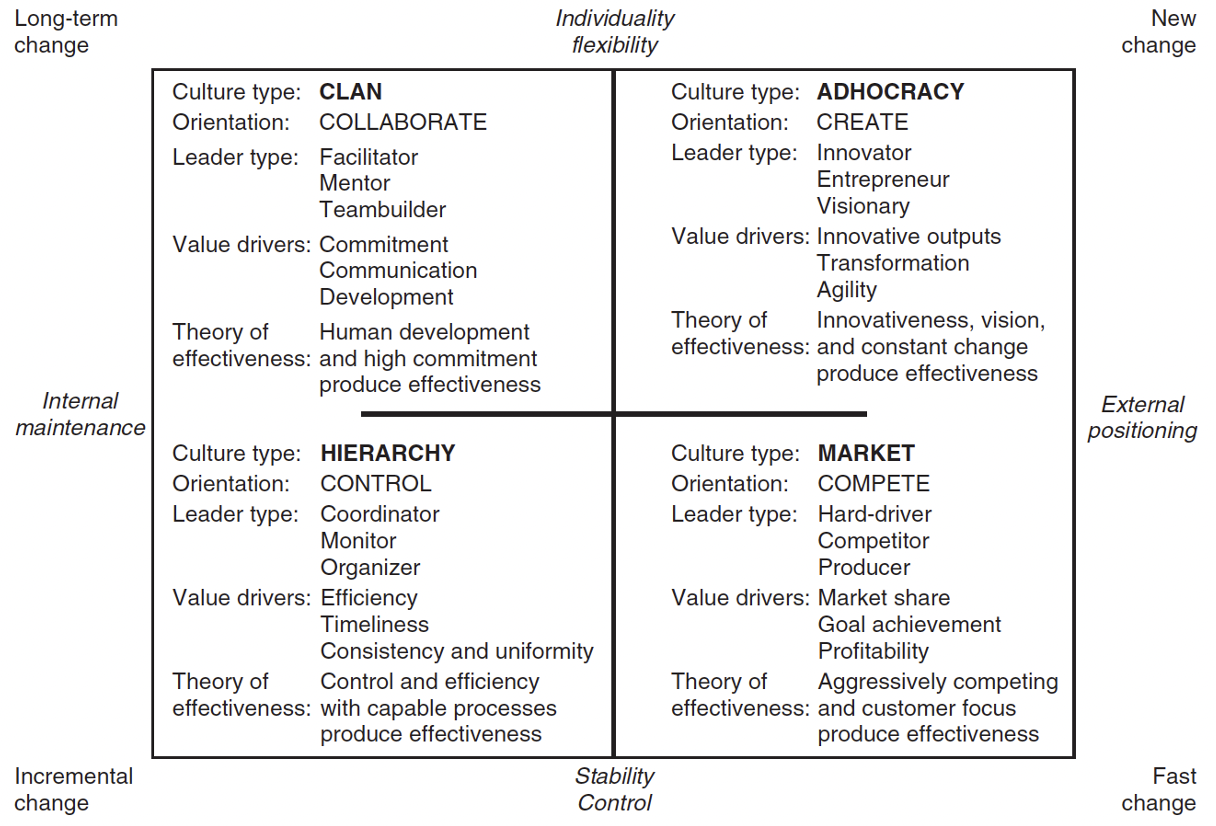

One important aspect of this intersection is culture and how it is measured. For instance, the Competing Values Framework (CVF) has helped researchers understand organizational culture. Paired with additional survey instruments such as E-Trust or the Technology Acceptance Models (TAM), researchers can better understand if particular cultures trust technologies more than other types. CVF is measured across six different organizational dimensions that are summarized by structure and focus. The structure axis ranges from control to flexibility, while focus axis ranges from people to organization, see figure 1.

Figure 1 – The Competing Values Framework – culture, leadership, value from Cameron, Kim S., Robert E. Quinn, Jeff DeGraff, and Anjan V. Thakor. Competing Values Leadership, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2014.

Most organizational cultures contain some measure of each of the four characteristics of the CVF. The adhocracy quadrant of the CVF, for instance, is characterized by innovation, flexibility, and increased speed of solutions. To this point, an NPS student researcher found that Marine Corps organizational culture was characterized as mostly hierarchical. The same researcher found that this particular group of Marine officers also preferred the Marine Corps move from a hierarchical culture towards an adhocracy culture. While the population in the study was by no means representative of the entire Marine Corps, it does generate useful insights for forming initial hypotheses and the need for additional research which explores whether hierarchical cultures impede trust in AI technologies. While closing this gap is important for assessing how a culture may need to adapt, actually changing deeply rooted cultures requires significant introspection and the willingness to change.

The ABCs: Adaptations for a Beneficial Culture

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast,” quipped the revered management guru, Peter Drucker—and for good reason. Strategies that seek to adopt new technologies which may replace or augment human capabilities, must also address culture. Cultural adaptations that require significant changes to behaviors and other deeply entrenched processes will not come easy. Modifications to culture require significant leadership and participation at all levels. Fortunately, organizational theorists have provided ways for understanding culture. One well-known organizational theorist, Edgar Schein, provides a framework for assessing organizational culture. Specifically, culture can be viewed at three different levels which consist of artifacts, espoused values, and underlying assumptions.

The Schein Model provides another important level of analysis for investigating the military organizational culture. In the Schein model, artifacts within militaries would include elements such as dress, formations, doctrine, and other visible attributes. Espoused values are the vision statements, slogans, and codified core values of an organization. Underlying assumptions are the unconscious and unspoken beliefs and thoughts that undergird the culture. Implementing cultural change without addressing underlying assumptions is the equivalent to rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. Therefore, what underlying cultural assumptions could prevent the Sea Services from effectively trusting AI applications?

One of the oldest and most ubiquitous underlying assumptions of how militaries function is the hierarchy. While hierarchy does have beneficial functions for militaries, it may overly inhibit how personnel embrace new technologies and decisions recommended by AI systems. Information, intelligence, and orders within the militaries largely flow along well-defined lines of communication and nodes through the hierarchy. In one meta-analytic review on culture and innovation, researchers found that hierarchical cultures, as defined by CVF, tightly control information distribution. Organizational researchers Christopher McDermott and Gregory Stock stated, “An organization whose culture is characterized by flexibility and spontaneity will most likely be able to deal with uncertainty better than one characterized by control and stability.” While hierarchical structures can help reduce ambiguity and promote stability, they can also be detrimental to innovation. NPS student researchers in 2018, not surprisingly, found that the hierarchical culture in one Navy command had a restraining effect on innovation and technology adoption.

CVF defined adhocracy cultures on the other hand are characterized by innovation and higher tolerances for risk taking. For instance, AI applications could also upend well-defined Military Decision Making Processes (MDMP). MDMP is a classical manifestation of codified processes that supports underlying cultural assumptions on how major decisions are planned and executed. The Sea Services should therefore reevaluate and update its underlying assumptions on decision making processes to better incorporate insights from AI.

In fact, exploring and promoting other forms of organizational design could help empower its personnel to innovate and leverage AI systems more effectively. The late, famous systems thinking researcher, Donella Meadows, aptly stated, “The original purpose of a hierarchy is always to help its originating subsystems do their jobs better.” Therefore, recognizing the benefits, and more importantly the limits of hierarchy, will help leaders properly shape Sea Service culture to appropriately develop trustworthy AI systems. Ensuring change goes beyond a temporary fix, however, requires continually updating the organization’s underlying assumptions. This takes double-loop learning.

Double-loop Learning

Double-loop learning is by no means a new concept. First conceptualized by Chris Argyris and Donald Schön in 1974, double-loop learning is the process of updating one’s underlying assumptions. While many organizations can often survive through regular use of single-loop learning, they will not thrive. Unquestioned organizational wisdom can perpetuate poor solutions. Such cookie-cutter solutions often fail to adequately address new problems and are discovered to no longer work. Rather than question the supporting underlying assumptions, organizations will instead double-down on tried-and-true methods only to fail again, thus neglecting deeper introspection.

Such failures should instead provide pause to allow uninhibited, candid feedback to surface from the deck-plate all the way up the chain of command. This feedback, however, is often rare and typically muted, thus becoming ineffectual to the people who need to hear it the most. Such problems are further exacerbated by endemic personnel rotation policies combined with feedback delays that rarely hold the original decision makers accountable for their actions (or inactions).

Implementation and trust of AI systems will take double-loop learning to change the underlying cultural assumptions which inhibit progress. Yet, this can be accomplished in several ways which go against the normative behaviors of entrenched cultures. Generals, Admirals, and Senior Executive Service (SES) leaders should create their own focus groups of diverse junior officers, enlisted personnel, and civilians to solicit unfiltered feedback on programs, technologies, and most importantly, organizational culture inhibitors which hold back AI adoption and trust. Membership and units could be anonymized in order to shield junior personnel from reprisals while promoting the unfiltered candor senior leadership needs to hear in order to change the underlying cultural assumptions. Moreover, direct feedback from the operators using AI technologies would also avoid the layers of bureaucracy which can slow the speed of criticisms back to leadership.

Why is this time different?

Arguably, the naval services have past records of adapting to shifts in technology and pursuing innovations needed to help win future wars. Innovators of their day such as Admiral William Sims developing advanced naval gunnery techniques and the Marine Corps developing and improving amphibious landing capabilities in the long shadow of the Gallipoli campaign reinforce current Service cultural histories. However, many technologies of the last century were evolutionary improvements to what was already accepted technologies and tactics. AI is fundamentally different and is akin to how electricity changed many aspects of society and could fundamentally disrupt how we approach war.

In the early 20th century, the change from steam to electricity did not immediately change manufacturing processes, nor significantly improve productivity. Inefficient processes and machines driven by steam or systems of belts were never reconfigured once they were individually equipped with electric motors. Thus, many benefits of electricity were not realized for some time. Similarly, Sea Service culture will need to make a step change to fully take advantage of AI technologies. If not, the Services will likely experience a “productivity paradox” where large investments in AI do not fully deliver the efficiencies promised.

Today’s militaries are sociotechnical systems and underlying assumptions are its cultural operating system. Attempting to plug AI application into a culture that is not adapted to use it, nor trusts it, is the equivalent of trying to install an Android application on a Windows operating system. In other words, it will not work, or at best, not work as intended. We must, therefore, investigate how naval service cultures may need to appropriately adapt if we want to fully embrace the many advantages these technologies may provide.

Conclusion

In a 2017 report from Chatham House titled, “Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Warfare,” Professor Missy Cummings stated, “There are many reasons for the lack of success in bringing these technologies to maturity, including cost and unforeseen technical issues, but equally problematic are organizational and cultural barriers.” Echoing this point, the former Director of the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (JAIC), Marine Lieutenant General Michael Groen, stated “culture” is the obstacle, not the technology, for developing the Joint All-Domain, Command and Control (JADC2) system, which is supported by AI. Yet, AI/ML technologies have the potential to provide a cognitive-edge that can potentially increase the speed, quality, and effectiveness of decision-making. Trusting the outputs of AI will undoubtedly require significant changes to certain aspects of our collective naval cultures. The Sea Services must take stock of their organizational cultures and apply the necessary cultural adaptations, while fostering double-loop learning in order to promote trust in AI systems.

Today, the Naval Services have a rare opportunity to reap the benefits of a double-loop learning. Through the COVID-19 pandemic, the Sea Services have shown that they can adapt responsively and effectively to dynamic circumstances while fulfilling their assigned missions. The Services have developed more efficient means to leverage technology to allow greater flexibility across the force through remote work and education. If, however, the Services return to the status quo after the pandemic, they will have failed to update many of its outdated underlying assumptions by changing the Service culture.

If we cannot change the culture in light of the last three years, it portends poor prospects for promoting trust in AI for the future. Therefore, we cannot squander these moments. Let it not be said of this generation of Sailors and Marines that we misused this valuable opportunity to make a step-change in our culture for a better approach to future warfighting.

Scott Humr is an active-duty Lieutenant Colonel in the United States Marine Corps. He is currently a PhD candidate at the Naval Postgraduate School as part of the Commandant’s PhD-Technical Program. His research interests include trust in AI, sociotechnical systems, and decision-making in human-machine teams.

Featured Image: An F-35C Lightning aircraft, assigned to Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 125, prepares to launch from the flight deck of the aircraft carrier USS George H. W. Bush (CVN 77) during flight operations. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Brandon Roberson)