By Ryan Martinson

A Chinese fishing vessel appears in a sensitive location—near the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea, a South China Sea reef, or just offshore from a U.S. military base. Is it an “ordinary” fishing boat, or is it maritime militia?

This straightforward question seldom yields straightforward answers. China does not publish a roster of maritime militia boats. That would undermine the militia’s key advantages—secrecy and deniability. Nor is it common for Chinese sources to recognize the militia affiliations of individual boats. Analysts can gather clues and make a case that a vessel is likely maritime militia, or not. That process requires painstaking effort, and the results are rarely definitive.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) may have made that process much easier, at least in the most contested parts of the South China Sea—the Spratly Islands. Since 2014, the PRC has built hundreds of large Spratly fishing vessels, collectively called the “Spratly backbone fleet” (南沙骨干船队). As I recently suggested at War on the Rocks, most if not all of these vessels are maritime militia affiliated. This insight can help overcome the perennial challenge of differentiating wayward Chinese fishermen from covert elements of China’s armed forces.

Backbone Boats are Militia Boats

In late 2012, PRC leaders decided to invest heavily in the modernization of China’s marine fishing fleet. Prompted by a proposal made by 27 scholars at the Chinese Academy of Engineering, they implemented a series of policies to help fishing boat owners replace their small, old wooden vessels with larger, steel-hulled craft. These programs provided subsidies to large segments of the Chinese fishing industry. But the most generous support was reserved for a specific class of fisherman: i.e., those licensed to operate in the “Spratly waters,” the 820,000 square kilometers of Chinese-claimed land and sea south of 12 degrees latitude.

The Chinese government, both at the central and local levels, allocated large sums of money to reimburse fishing boat owners willing to build new Spratly boats. Hundreds of Chinese fishing boat owners took them up on this offer. The new boats constituted the “Spratly backbone fleet.”

The PRC was very particular about what kinds of boats it wanted in the new fleet. In a January 2018 interview, the Party Secretary of a Guangxi-based firm named Qiaogang Jianhua Fisheries Company (桥港镇建华渔业公司) acknowledged that while the subsidies were quite large, the new boats had to meet very exacting standards. According to the Secretary, surnamed Zhong, the vessels must be quite large, have powerful engines, and be equipped with advanced refrigeration units, among “many, many” other stipulations. Zhong declared, “The document listing these requirements (批文) is very thick. If you don’t adhere to these stipulations, then there’s no subsidy.”

Aside from controlling what types of boats got built, Beijing likely desired some control over how the new boats got used. If deployed effectively, their actions could, like at Scarborough Shoal in 2012, enable new territorial acquisitions. Conversely, if misused, they could damage China’s reputation and even precipitate a violent clash. When the program began, China already had in place a system for controlling the activities of its fishing boats in contested waters: the maritime militia.

The “maritime militia” (海上民兵) is the saltwater element of China’s national militia. Like the People’s Armed Police and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), it is a component of the country’s armed forces. Most members of the maritime militia have day jobs, often as fishermen. However, their affiliation with the militia means that their vessels can be “requisitioned” (征用) to participate in training activities and conduct missions (service for which they are compensated). Militia members are trained and managed by PLA officers assigned to People’s Armed Forces Departments (PAFDs) in the city, county, or town in which the militiamen reside.

Subsidies for construction of the Spratly backbone fleet have been channeled both to existing members of the maritime militia and unaffiliated fishing boat owners that were willing to take the oath as a condition for the money. Among the first to receive the new boats, members of the Tanmen maritime militia benefited from the first approach. Spratly backbone boats registered to Hainan’s Yangpu Economic Development Zone offer an example of the second.

The Spratly backbone fleet appears to be managed by the coordinated efforts of provincial fisheries authorities and the provincial military system (of which PAFDs are a part). The most compelling support for this thesis comes from a 2017 report by the Guangzhou-based MP Consulting Group, which was hired to audit Guangdong’s Marine and Fisheries Bureau. The resulting 96-page document was subsequently posted on the website of the Guangdong Department of Finance.

In their report, MP consultants assessed the Bureau’s success at achieving the seven goals established for 2016. Most were domestic regulatory functions, irrelevant to this story. However, the Bureau’s seventh goal set out the organization’s mission to help protect China’s “rights” in disputed maritime space in the South China Sea. MP consultants generally gave favorable marks on this account, listing eight noteworthy achievements. These included the Bureau’s role in “promoting the construction of maritime militia forces.” Specifically, the Bureau spent 2016 clarifying the division of responsibilities between it and the provincial military district with respect to the “construction, daily operation, combat readiness training, and other relevant tasks” of the Spratly backbone fleet. This statement indicates that the Guangdong elements of the Spratly backbone fleet—and, by extension, those backbone vessels based in Guangxi and Hainan provinces—are organized into militia units jointly managed by the provincial military district and the provincial Marine and Fisheries Bureau.

Other evidence supports the hypothesis that “backbone” boats are militia boats. In August 2020, for instance, the Jiangmen City branch of the Bank of Guangzhou released a summary of its contributions to the local economy. Among these, the branch cited a 97 million RMB loan it provided to an unnamed “top tier fishing company” to build 11 Spratly backbone boats. The bank unwittingly revealed that these new fishing vessels also had “militia functions” (民兵用船功能).

A generic employment contract for crew members embarking on Spratly backbone boats offers additional evidence. The contract—which was uploaded to a Baidu document sharing platform in February 2019—outlines terms for employment at the Shanwei City Cheng District Haibao Fisheries Professional Cooperative (汕尾市城区海宝渔业专业合作社). While little is known about this cooperative, its members are clearly active in the Spratlys. Indeed, its operations manager, Mr. Zhang Jiancheng (张建成), serves as the General Secretary of the Shanwei Spratly Fishing Association (汕尾市南沙捕捞协会).

The Haibao Fisheries contract makes clear that its backbone boats are militia boats, without actually using the words “maritime militia.” It contains a section on “rights protection requisitioning” (维权征用), i.e., removing the boat from production so that it can serve state functions in disputed maritime space. According to Article 2 in that section, if required for “national defense,” the fishing vessel and its crew must “participate in training activities and rights protection tasks, and support military operations.” Article 2 also indicates that crew members must comply with arrangements made by the fishing cooperative and “obey the command of the military” and other government authorities. Article 4 states that if and when the fishing vessel is requisitioned, the boat and its crew must “obey the command of the state,” operating in the manner required, mooring in the determined location, and “completing the operational tasks according to the specific requirements.”

Section 6 outlines the rules governing crew behavior, both ashore and at sea. For example, crew members must not gamble, solicit prostitutes, or visit strip clubs while in port (Article 6). The rules also include content specific to the vessel’s militia functions. Article 7 proscribes taking photos and “divulging the secrets of the boat.” Without the permission of the captain, crew members cannot bring outsiders aboard the boat to view its “design structure and internal setup” (设计构造和内部设置).

Implications

In this article, I have argued that most if not all Spratly backbone boats are militia boats. They may actually catch fish, but their militia affiliation makes them available for state and military tasking. If this conclusion is correct, it offers useful new ways to identify Chinese maritime militia forces operating in the Spratly waters. While the PRC does not publish lists of active maritime militia boats, it does share information about which boats belong to the Spratly backbone fishing fleet. This can serve as an indicator of militia status.

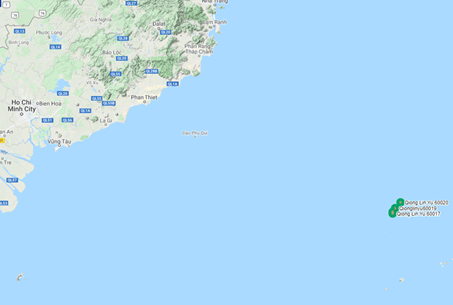

How might this work in practice? At the time of this writing, a team of four Chinese fishing boats is operating illegally within 200 nautical miles of Vietnam’s coast, i.e., within the country’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). The four vessels are named Qionglinyu 60017, 60018, 60019, and 60020, respectively, indicating they are registered to Hainan’s Lingao county (临高县). Vietnamese maritime law enforcement authorities could evict them, but before doing so they might ask, are they maritime militia?

My answer: “very likely.” A quick sifting of open-source materials reveals they are all backbone boats. This information appears in a March 2020 open letter posted on the website “Message Board for Leaders” (领导留言板). In it, the boat owners entreat PRC officials to restore fuel subsidies and other rewards for operating in “specially-designated waters” in 2018. Likely amounting to hundreds of thousands of RMB, the subsidies were withheld as punishment for operating in the Spratlys without the required licenses. To elicit special consideration, they emphasized that their four vessels were Spratly backbone boats. (Their ploy ultimately failed, as the Lingao County Bureau of Agriculture responded to their letter with a firm but polite refusal to change their decision.)

Southeast Asian countries can and should compile lists of known Spratly backbone boats. They can start with local newspapers, which are a great source for such information. In December 2016, for example, Zhanjiang Daily published an article about the launching of the city’s first Spratly backbone trawlers: the 48-meter (577 ton) Yuemayu 60222 and 60333. Registered to the city’s Mazhang District, the craft are owned by Zhanjiang Xixiang Fisheries (湛江喜翔渔业有限公司). With these clues in hand, one can then try to learn the identities of the company’s two other Spratly backbone boats, then still under construction.

The websites of Chinese shipbuilding companies are another useful source of information. Those with contracts to build backbone boats often issue news releases when these vessels are launched or delivered. In October 2017, for instance, the Fujian-based Lixin Ship Engineering Company launched five very large Spratly backbone trawlers built for a Guangdong fishing company, Maoming City Desheng Fisheries Limited. The five boats were delivered two months later. They included Yuedianyu 42881, 42882, 42883, 42885, and 42886. The boats were 63.6 meters in length and had the large (1244kW) engines typical of the backbone fleet. Of note, Desheng Fisheries is the same company that owns Yuemaobinyu 42881, 42882, 42883, 42885, and 42886, all spotted moored at Whitsun Reef in March. Indeed, they may be the very same boats (their names having been slightly altered in the years since they were built).

Provincial and municipal governments may be the most valuable sources of all. In November 2020, the Guangdong Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Affairs released information about the province’s Spratly (“NS,” for nansha) fishing license quota for 2021. The document indicated that 255 Guangdong boats would receive Spratly fishing licenses this year, among which 185 would go to backbone boats and 70 would go to “ordinary boats” (普通渔船). The Bureau attached an Excel spreadsheet listing the chosen vessels. The document omitted Table 1, containing the list of backbone boats. But it did include Table 2, listing the 70 “ordinary” fishing boats. Since only two types of Guangdong boats operate in the Spratlys—i.e., ordinary and backbone—any Guangdong boat there and not found in Table 2 must be a backbone bone, and therefore presumed militia.

These data help shed light on recent events. In March and April 2021, the Philippine Coast Guard released photos of Chinese fishing boats loitering at Whitsun Reef. Thanks to the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI), we know the identities of 23 of them.

Both AMTI and the Philippines Coast Guard classified them as “militia.” They are right. All are from Guangdong. All are absent from Table 2. And that makes them no “ordinary” boats.

Ryan D. Martinson is a researcher in the China Maritime Studies Institute at the Naval War College. He holds a master’s degree from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University and a bachelor’s of science from Union College. Martinson has also studied at Fudan University, the Beijing Language and Culture University, and the Hopkins-Nanjing Center.

Featured Image: In this photo provided by the National Task Force-West Philippine Sea, Chinese vessels are moored at Whitsun Reef, South China Sea on March 27, 2021. (Philippine government photo)

This piece is a good step in the right direction in that it focuses on data and refrains from unsupported definitive conclusions. But as the author acknowledges at the beginning, the answers to simple questions regarding maritime militia—like ‘is this one?’– are “rarely definitive”. Indeed his summary of his meticulous research raises as many questions as it answers.

If the purpose of China’s maritime militia is to enforce the government’s its maritime or territorial claims why must “Spratly backbone boats’ “be equipped with advanced refrigeration units?” That seems to confirm that they are dual purpose boats. He also finds that “most members of the maritime militia have day jobs, often as fisherman.”

These findings seem to confirm that it is difficult to tell from its appearance whether a particular boat is maritime militia—at any given time. Yet the author concludes that “all Spratly backbone boats are militia boats.” I would suggest that they may all be ‘potential’ maritime militia.

A conclusion I draw from his analysis is that many of China’s fishing boats can be used for state tasks. Thus they are maritime militia—or acting as such– when they are engaged in tasks ordered by the state. And when they are not, they are ordinary fishing boats. Without a public declaration thereof, the evidence is only circumstantial. Moreover, whether a particular Chinese fishing boat is acting as maritime militia is in the eye of the beholder. For example, the fishing boats moored at Whitsun Reef were not breaking any laws. https://www.lawfareblog.com/whitsun-reef-incident-and-law-sea It is not clear why they were there in such great numbers. China claimed they were avoiding bad weather. That could mean the present or expected/predicted. Without first hand information, it cannot be proven this is not the reason they were there. Moreover when they move from one China-claimed territorial sea to another, they are exercising freedom of navigation.

The author rightly uses conditional language throughout. But he also introduced a new fuzzy phrase “maritime militia affiliated,” as in “most if not all of these vessels are maritime militia affiliated.” That may be – but again – it depends on what they are doing or perceived by China’s critics to be doing at any given time to conclusively identify them as acting as maritime militia.

Also if China uses most of its fishing boats and crew as militia, why did it punish some for operating in the Spratlys without the required licenses. And why did it punish some fishing boats for illegal fishing by withholding subsides? This information undermines the author’s contention that all or most of them are maritime militia affiliated..

Similarly, why does China differentiate between “backbone boats and ordinary boats” in the granting of licenses. One possible conclusion is that not all Chinese fishing boats operating in the Spratlys are maritime militia operating as maritime militia. The problem is demonstrated by his conclusion that 23 of some 220 boats are definitely maritime militia.

So does that mean the other near 200 boats are not and will not act as such?

Researchers have a long way to go to prove that at any given time a Chinese fishing boat is operating on behalf of the state and is thus acting as maritime militia regardless of whether its construction was subsidized for that purpose.

Mark J. Valencia

Adjunct Senior Scholar

National Institute for South China Sea Studies

Haikou, China

Any militia must have discipline. Fishing without a license would hazard the unity of the entire fishing fleet in its main task: feeding China. Perhaps some militia boat owners began “feeling their oats” and tried to game the system a little. They had their hands dlapped, which sent a message to all fishing boats, not jusy militia ones. Yes- they are fishermen. Yes – they are militia. As we used to say in Canada: ” Twice the citizen”.

The Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations states, “International law defines a warship as a ship belonging to the armed forces of a nation bearing the external markings distinguishing the

character and nationality of such ships, under the command of an officer duly commissioned by the government of that nation and whose name appears in the appropriate service list of officers, and manned by a crew which is under regular armed forces discipline.”

Warships can exercise sovereign immunity, but are also restricted from carrying out certain activities in waters belonging to other countries; some of these activities could be construed as acts of war, due to the vessel’s status as a warship.

The apparent value of a dual-purpose fishing fleet/maritime militia appears to be that vessels can gain legal access to certain waters, while then carrying out (or being ready to carry out) activities typically restricted to government or military vessels, such as gathering intelligence or kinetically gaining/defending portions of the sea (to include damaging/sinking other vessels or harming/killing people).

It seems useful to know whether a given fishing boat also has a trained and equipped paramilitary crew aboard, and whether they might engage in paramilitary-type activities in another country’s waters/EEZ in addition to their fishing “day jobs.” Legally, it seems the vessel’s official status (civilian or military) would be judged according to its compliance with warship definitions in international law, at the time of any disputed activity. That being said, China has not abided by UNCLOS decisions it disagrees with, nor has the international community taken kinetic measures to enforce those decisions.