By Ching Chang

Last November, after an augmented meeting on reformed policies hosted by the Central Military Commission in Beijing, the longtime prepared and formulated reform of the People’s Liberation Army was eventually activated. This Meeting was assembled on November 24, 2015, and attended by all the major senior cadres of the defense establishment and various services.

Many features of the coming national defense and military reform were disclosed through the defense spokesmen system right after the meeting. Given the length of the meeting and the scale of participants, it is believed that directives of the reform were already settled by high authorities. No substantial discussion likely took place in this significant gathering of defense elites. Flag officers and commanding generals are only told the predetermined implementation plan. Somehow this reform may seemingly be like the traditional saying, “Theirs not to reason why. Theirs but to do and die.”

Later at the end of 2015, the Central Military Commission of the People’s Republic of China released a guideline known as “The Opinions of the Central Military Commission on Deepening the National Defense and Military Reform” (中央軍委關於深化國防與軍隊改革的意見), which provided more detail information about items of the inevitable restructuring process. Many political commentators and military observers put their efforts on features subsequently announced by the Chinese military including establishing new units, redefining AORs (Areas of Responsibility) and name list of the freshly appointed military leadership.

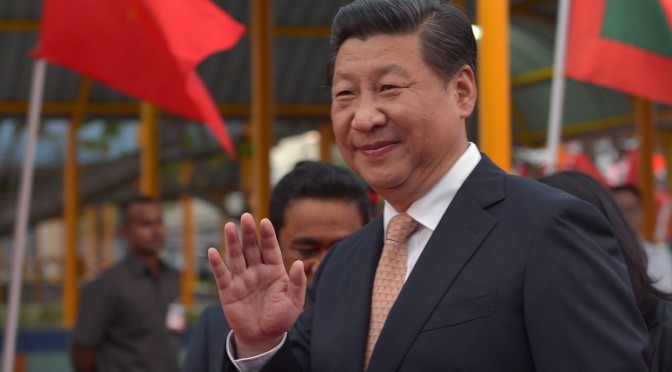

Indeed, grasping the progress of the reorganization can be very helpful to acquire information about many features but it is less productive for us to understand the logic behind the reform process. Understanding the nature of the PRC’s national defense and military reform is more valuable to access the thinking behind the decision making modus operandi of the People’s Liberation Army leadership or even their political masters. By reviewing the history of the military reform planning process started right after Mr. Xi Jinping inaugurated the Chairman of the Central Military Commission until now and the contents of the associated policy documents, we may conclude key attributes regarding the nature of the PRC’s national defense and military reform.

First, this reform is parallel to the tempo of Chinese society by its essence. It is only a part of the overall reform in Xi’s political engineering blueprint. All the issues noted in this deepening national defense and military reform process not only reflect demands from the external strategic environment but also attempt to satisfy the expectations originating from the People’s Liberation Army elites.

Why may it take more than two years to formulate a guideline for substantiating the military reform? The answer is simple and straightforward. The defense and military reform itself does not act alone. There are many factors associated with other governing mechanisms in Chinese society. The military reform is only a segment of the overall reform endeavor advocated by the Chinese Communist Party. As the defense authority would like to proceed with its reform efforts, it is necessary for them to acquire mature social prerequisites and suitable political conditions.

The overall reform policy was actually settled by the Third Plenary Session of the Eighteenth Chinese Communist Party Central Committee. On November 12, 2013, a policy document known as “The Decision on Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reforms” (中共中央關於全面深化改革若干重大問題的決定) was approved by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. In the document containing sixteen chapters, Chapter Fifteen includes Point 55 to 57 which present the following directives:

Chapter XV—National defense and military reform

The People’s Liberation Army must be loyal to the Chinese Communist Party, be able to win and be persistent with its good traditions.

- Deepen the reform of the military’s composition and functions. Improve the combined combat command systems of the Central Military Commission and military commands. Push forward reform of training and logistics for joint combat operations. Optimize the structure and command mechanism of the Armed Police Force. Adjust the personnel composition of the military and reduce non-combatant departments and staff members.

- Boost the adjustment of military policies and mechanisms. A modern personnel system for officers will gradually take shape with the establishment of an all-volunteer officer system as the initial step. Improve management of military expenditures.

- Boost coordinated development of military and civilian industries. Reform the development, production and procurement of weapons. Encourage private businesses to invest in the development and repair sectors of military products.

Given the complexity and the structure of this policy document, this is why it took such a long period of time after Xi was elected to chair the Central Military Commission and declare his intention of military reform in the first Central Military Commission Standing Committee Meeting. Further. The People’s Liberation Army needs resources granted by the whole of society to support its own reform. Chinese society must accommodate decommissioned manpower released by the military during this reform process. The military reform is therefore a segment in the larger social and political reform project. How can you put your eyes only on a single branch but ignore the whole tree?

Second, the military reform in the PRC once again reaffirmed the Chinese Communist Party’s leadership over the People’s Liberation Army. Although many features exposed by the reform themselves are seemingly promoting the military professionalism, nevertheless, according to the decision-making procedures, the political masters of the military still hold a tight grip on the armed forces in China as always addressed by the tradition known as “the party commands the gun.”

As already mentioned, Mr. Xi has clearly blown the trumpet of military reform right after taking the power of military command in the First Plenary Session of the Eighteenth Chinese Communist Party Central Committee. No key decision had been made nor was clear policy declared on military reform until the eventual policy of a comprehensive social and political reform project was settled by the Chinese Communist Party in its Third Plenary Session of the Eighteenth Central Committee occurring 9–12 November 2013.

The Leading Group for the National Defence and Military Reform of the Central Military Commission (中央軍委深化國防與軍隊改革領導小組) was immediately organized and personally chaired by Mr. Xi, the Chairman of the Central Military Commission, and held its first meeting in early 2014. The second meeting of this leading group was held on January 17, 2015. At the moment, it was known that the military had already successfully coordinated with other government departments and local governments to support their reform tasks through party arbitration mechanisms. Expected resistance within the military was also eliminated by these external sponsorships. It vividly indicates the role played by the communist party within the reform process.

The Proposal of Deepening National Defense and Military Reform Overall Plan (深化國防與軍隊改革總體方案建議) eventually completed drafting in the third meeting of the Leading Group for National Defence and Military Reform of the Central Military Commission on July 14, 2015. It is essential to note that this proposal still needs to be reviewed by the Central Military Commission Standing Committee by July 22 even though both mechanisms are chaired by Mr. Xi. Finally, the proposal was approved by the Political Standing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, again chaired by Mr. Xi, later on July 29.

After the political decision was made by the party decision-making mechanism, the Central Military Commission Standing Committee in its routine meeting on October 16 started to inspect the Implementation Plan for Administration and Command Structure Reform (領導指揮體制改革實施方案) submitted by the Leading Group for National Defence and Military Reform of the Central Military Commission according to the party-approved proposal. All features of the PRC’s military reform presented to the public was actually settled by this implementation plan, not from any discussion in the augmented meeting assembled on November 24, 2015. In this decision process proceeding between party and military decision making system, even these mechanisms are basically chaired by Xi. There is no doubt the Chinese Communist Party is still effectively exercising its leadership over the People’s Liberation Army. Regardless of the military professionalism indicated by the features shown in the military reform, the party is still the boss of these military professionals.

Last but not the least, the transparency of the military reform is unquestionably significant. There is a general trend of accusing the transparency of Chinese policies or actions in the community of Chinese observers. Rarely do Chinese experts ever thoroughly read these documents openly released by the communist authorities before criticizing transparency. As noted in this article, dates of decision making meetings and documents of reform policies are essentially quite transparent. At least in two documents already mentioned, the Decision on Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reforms and the Opinions of the Central Military Commission on Deepening the National Defense and Military Reform, are openly available. All features attracting media concern are already listed by these two documents.

This military reform may affect the careers and families of many military personnel. It may also undermine interests of defense industries and local economies. Social engineering of this scale cannot be totally concealed. Three hundred thousand military personnel will be decommissioned by this reform. Many units will be eliminated and their assets need to be disposed of. It is impossible to shut the door and engage with the reform only by the military itself. Can Chinese military experts know the right sources to understand the nature of the People’s Liberation Army’s reform?

The content of these two documents not only address the tasks that need to be done but also consequences that should be actively prevented. This position is considerably pragmatic. Many possible corruptive actions are warned of. To some extent, no intention to ignore the dark side of the human nature that possibly fishing in the trouble water is also evidently presented by the texts of the policy document. These possibly embarrassing issues can be noted by texts with no preservation. The degree of transparency should be undeniable.

However, it is necessary to remember that the title of the Opinions of the Central Military Commission on Deepening the National Defense and Military Reform implies that there are still many uncertainties existing within the future reform process. According to Article Nine of the Procedures for Handling Official Documents in the Administrative Departments of the Government for the PRC, the definition of a document with the title of “opinion” is “An opinion shall be given when providing opinion over important issues and the solutions thereof.” Unlike “decision” its definition is “A decision shall be given in the following situation: deciding on important issues or actions, granting citations to relevant work units and personnel, changing or cancelling inappropriate decisions made by sub-branches.” Are the solutions of all the PRC’s military reform tasks completely settled? Obviously not! Otherwise, the document would be titled with “decision,” not “opinion.”

The features of the military reform involve much information to analyze, but to understand the nature of the People’s Liberation Army reform is the essential foundation to solve this game of jigsaw. Without knowing the fundamental characteristics of this reorganization process, we may only act like a dog chasing its own tail with no result at all.

Chang Ching is a Research Fellow with the Society for Strategic Studies, Republic of China. The views expressed in this article are his own.