By Zachary Abuza, PhD

Security in Sabah

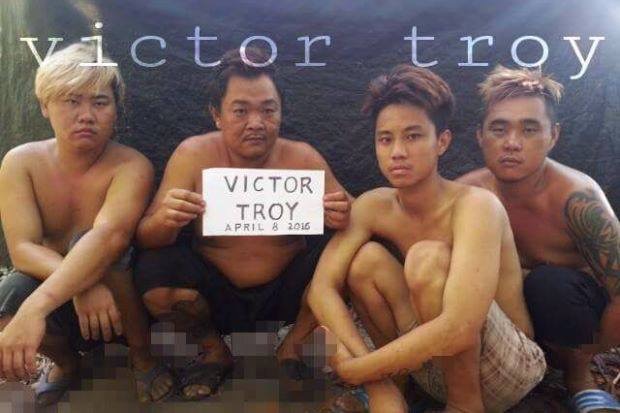

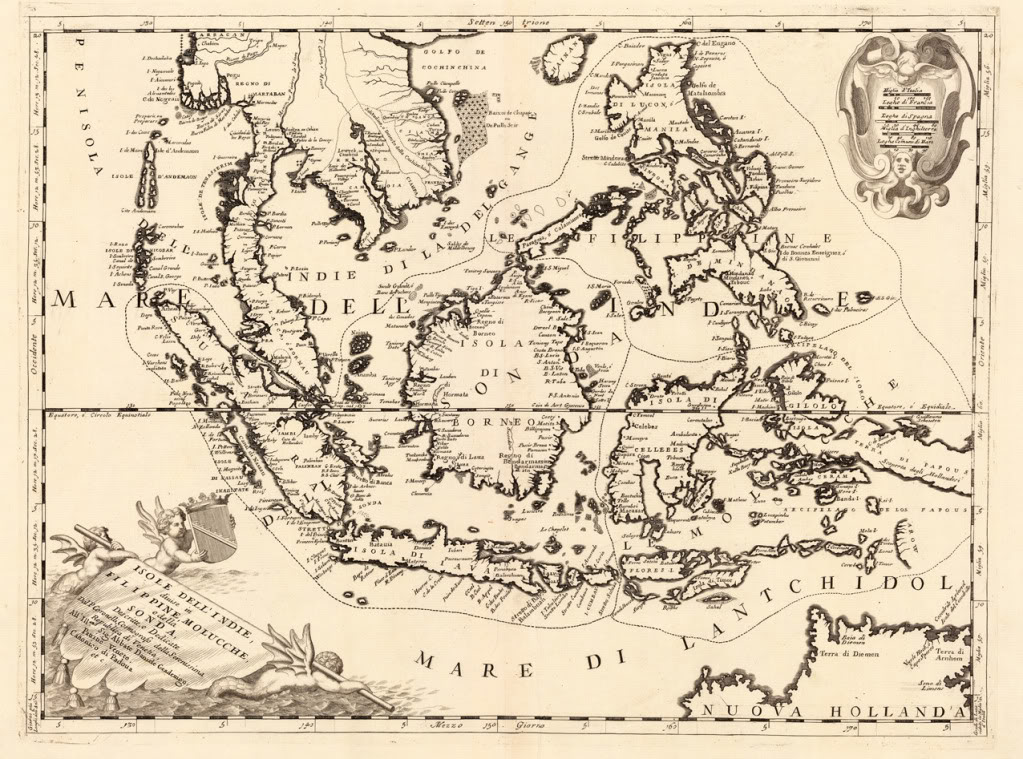

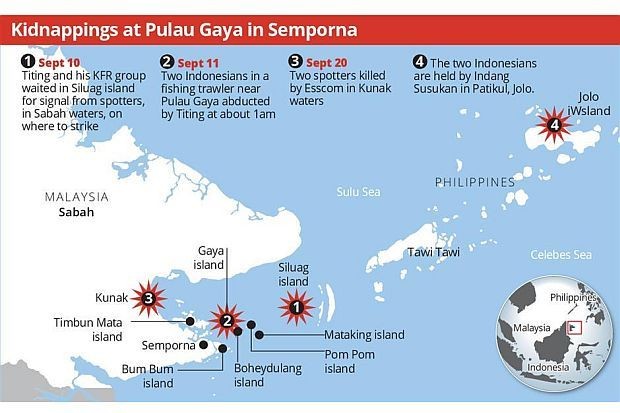

In 2013, a group of several hundred armed militants from the southern Philippines landed in the Sabahan city of Lahud Datu in an attempt to retake the land in the name of the Sultan of Sulu. 10 security force personnel and 6 civilians were killed. 45 militants were killed, 30 were captured and nine were sentenced to death. Since then, the eastern Sabah State of Malaysia has witnessed a series of armed incursions, kidnapping for ransom, one of which led to the decapitation of a Malaysian policeman. Additionally, from March 2016 to April 2017, a spate of maritime kidnappings threatened regional trade. According to open source data, 70 seamen from six countries were taken in 19 separate incidents.1 Five were killed during the attacks, while others died while in captivity. By the fall of 2016, pirates were attacking large ocean going vessels, including Korean and Vietnamese vessels, while a Japanese ship took evasive action.

This forced the establishment of trilateral maritime patrols involving the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia. While that led to a sharp decline in maritime incidents, they recommenced in 2018 and again in June 2019. Gunmen kidnapped 10 Malaysian fishermen, though they were soon released. Since 2017, Malaysian police have arrested 39 members of the Abu Sayyaf (ASG), a jihadist group, including two in 2019. Additionally, some of the most important terrorist cells arrested in Malaysia have been in Sabah, a key transit route for foreign fighters entering and leaving the Southern Philippines, including at least three of five suicide bombers since July 2018. All of this points to the fact that Sabah is not only the crux of Malaysia security, but regional security as well.

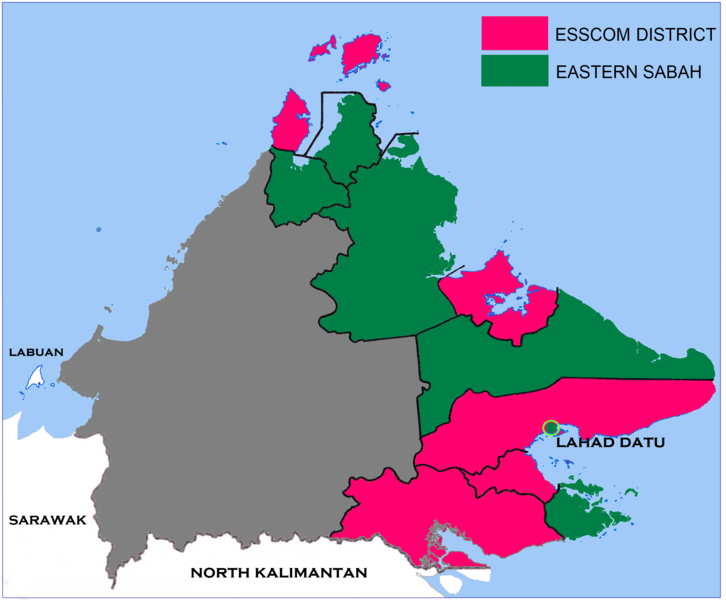

ESSCOM

The Malaysian government established the Eastern Sabah Security Command (ESSCOM) in April 2013 in response to the chaotic and un-coordinated response to the Lahud Datu incursion.

The organization was supposed to be a coordinated and joint operational headquarters for the Malaysian Armed Forces (RMAF), the Royal Malaysian Police (RMP), including the Special Branch which is the lead counterterrorism agency, the maritime police, and the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA). The navy has deployed special forces to the region, and upgraded their fleet of small craft, as well as set up two offshore vessels as operational hubs. The maritime police established two operational bases on coastal islands.

Starting in 2015, Malaysia deployed the first of eight advanced coastal radar stations to give them greater maritime domain awareness (MDA). It was an important step. In 2018, Malaysian officials claimed to have thwarted 10 incursions by ASG militants, and killed nine kidnapping suspects in maritime skirmishes. The only successful maritime kidnapping in 2018, was that of two Indonesian fishermen.

But there were a number of shortcomings. Most importantly, Malaysia has little experience in joint operations, let alone inter-agency operations. ESSCOM was faced with an almost insurmountable challenge. It also goes to the highest levels as there is no formal National Security Council-like process.

Even with the nascent inter-agency planning and operational process, rivalries remained problematic. In its first operational year in 2014, it had a budget of RM660 million ($200 million at the time), but there were immediate fights over it. The army still controls the lion’s share of the ESSCOMM budget, despite being a largely maritime and policing issue. Many security analysts, however, noted that the police were the worst when it comes to coordination and inter-agency cooperation. That intransigence has given the army the space to step in. When there is close cooperation within ESSCOMM, it tends to come down to personal relationships, rather than formal coordinating mechanisms and processes. But even operational areas of responsibility between the RMAF, the police and MMEA were not always delineated and de-conflicted.

Budgets remain very tight. Even before the historic victory of the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government, the first opposition government in 61 years, Malaysian defense spending began to fall from its peak in 2015. The $4.5 billion debt that the PH government inherited from the government of Najib Razak from its massive 1MDB fraud case will mean that Malaysian defense spending will continue to fall as the government is predicting large deficits for the next few years. In the past five years, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s military expenditure data set, Malaysia’s defense budget fell from RM16.1 billion to RM14 billion, a 13 percent decline. In dollar terms, in the past five years, Malaysia’s defense budget contracted by 22 percent from $4.1 to $3.2 billion. Malaysia has among the lowest defense expenditure as a percent of government spending, at 4.3 percent. This has declined from 5.5 percent a decade ago. In the past decade, Malaysian defense spending as a percent of GDP was cut in half from 2 to 1 percent. We see this in terms of per capita spending as well. In the past five years, Malaysia’s defense spending has fallen from $160 to $108 per capita, a 32 percent decline.

But the problem isn’t simply budgetary; it is one of priorities. The RMAF budget is dominated by the army, despite the fact that most of the country’s security threats are maritime in nature. The army’s budget is larger than the combined budget of the navy and air force, and it has 80,000 men compared to the navy and air force with only 15,000 each. Moreover, this fiscal austerity is shared across the agencies.

Another issue is the sheer scope of the area to patrol. The coastline of ESSCOMM alone is around 1,400 kilometers, and includes seven districts in eastern Sabah. There have been discussions about expanding it, but to date that has not happened. The ratio of resources to area is just not there. In addition to the geographical scope is the fact that Sabah is home to an estimated 800,000 illegal migrants, most of whom are ethnic Tausigs, the same ethnicity of most of Abu Sayyaf. Those clan and kinship ties have proven invaluable for Abu Sayyaf and other kidnapping syndicates.

Finally, there is the fact that Sabah is treated differently. There is a sense of “internal colonialism,” which is shared by both Sabahans and peninsular Malaysians. RMAF forces from Peninsular Malaysia resist deployment there.

Reforms in the Offing

The news is not all bad. There is an understanding of ESSCOMM’s weaknesses and an acknowledgement that it needs to be fixed. A former Sabah assistant minister, Ramlee Marahaban, from the former ruling UMNO party, provided a solid criticism. For him it was not a need for more resources or personnel, but a shift from army authority to the police and MMEA, with clearer lines of authority:

“The weakness of ESSCOMM, which has been in operation for six years now, is due to the lack of a clear jurisdiction of the agencies involved. Full power should be given to the police and maritime agencies as they have the authority to arrest, investigate, and prosecute. The army can support through asset deployment, including usage of radar. The number of assets and personnel stationed at the Eastern Sabah Security Zone (ESSCOMM) is more than sufficient but the weakness lies in the overlapping of power and duties.”

When the author interviewed senior members of the Pakatan Harapan government, they broadly concurred with this. Though they would not spell out the details of the ESSCOMM

reorganization, they made clear that it would be much more in terms of statutory authorities, chain of command, and procedures, rather than a host of new resources, manpower, or assets. The Minister of Defense Mohamad Mat Sabu announced the government’s intention to re-organize ESSCOMM, on 6 May 2019, which has since been endorsed by the Inspector General of the Police. What is more likely in terms of personnel is changes in command of certain bases or security sectors.

The Deputy Minister of Defense, Liew Chin Tong, has made maritime security a priority: “[W]e have to realise that Malaysia is a maritime nation and the seas are our lifeline, with many resources coming from the waters, and many strategic water spaces to protect in an increasingly complex security environment.” While he acknowledged that the army’s budget and size was unlikely to change, he was insistent that they would have to broaden the scope of its operations and take on some maritime roles. As he wrote, “The army has to learn to swim.” The army will soon deploy one battalion to train alongside naval special forces in Sabah. Perhaps more importantly, the Army is contemplating a major reorganization, along territorial lines, which would give Sabah greater primacy. But more importantly he prioritized joint operations, and at least pointed to “whole of government” solutions to Malaysian security concerns. These plans will be officially rolled out in the 2019 Defense White Paper, which should be released soon.

While the overall budgetary pressure on the RMAF is large, the budgets allocated for Sabah-deployed forces have not taken such hits. Prime Minister Mahathir Mohammad is not a fan of conventional military spending, which he views as being something that antagonizes China. The Defense White Paper has prioritized non-traditional security threats, including those in Sabah, such as kidnapping for ransom and terrorism, in particular.

The government has a political incentive to improve the security situation in Sabah. The Sabah Heritage Party (Warisan) is a key member of the governing coalition with 8 of 121 parliamentary seats; and the state’s Chief Minister, Datuk Seri Shafie Apdal, heads the party. In the 2018 election, Sabah proved to be a critically important vote bank, and it will remain so. The Sabah government itself is supportive of ESSCOMM. Shafie Apdal said in June 2019, “We welcome whatever changes, whether it is for cost cutting or not, but most important is the effectiveness of ESSCOMM’s role in Sabah.” He previously made it very clear that ESSCOMM is not going away. The local economy in general, and tourism sector in particular, have been very hard hit by the kidnappings. Moreover, the curfews are very unpopular.

The Special Branch also knows how important Sabah is in terms of counterterrorism. This area remains the key logistics hub for getting militants in and out of the southern Philippines. In 2018 alone, Malaysian police arrested 29 foreign fighters in Sabah. This is critical as the southern Philippines remains a key draw for foreign fighters following the loss of the ISIS caliphate in Syria and Iraq, and it is the only place in all of Southeast Asia where militants have any possibility of controlling territory. Militants in the Southern Philippines continue to bill themselves as the leaders of the Islamic State in East Asia.

While Malaysian security forces have publicly stated that they have not seen a revival of JI networks, as is very evident in Indonesia, privately, a number of Malaysian security analysts have told the author this is nonsense, pointing to the resilience of Darul Islam Sabah, which since 2014 has been working with Indonesian JAD and other pro-ISIS groups in the Philippines, but whose ties to traditional JI networks remains deep and enduring. In the ideology of both JI and ISIS is the concept of “Hijrah,” emigrating to join a struggle.

MMEA’s Growing Pains

One of the keys to Sabah’s security is the development of the MMEA, which is lauded for their professionalism and lack of corruption. It was established in 2004. While the police feared losing their maritime police functions, the Navy advocated for it because they didn’t want brown water constabulary functions. The MMEA was originally under the Prime Minister’s Department, though since late 2018 it has been under the Ministry of Home Affairs. To date, it has been headed by a uniformed naval officer, while much of its senior leadership are also naval personnel. But now in its 16th year, it is developing its own leadership from within its ranks.

Like every security agency in Malaysia, its budget remains tight. It is currently constructing three offshore patrol vessels (OPVs) under license from the Netherland’s Damen Group. Japan recently donated two OPVs from its Coast Guard, as it has with the Philippines and Vietnam. The Malaysian Navy transferred two OPVs to them, as well. However, the deployment of smaller fast craft is what remains so important in the Sulu Sea off of Sabah.

While Sabah remains very important for MMEA, it has a host of other concerns: the territorial dispute with Indonesia, the Strait of Malacca, and countering Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) gray zone operations in the South China Sea, including defending Petronas oil platforms at Luconia Shoal that have been increasingly harassed by the CCG. The organization also has limitations in its personnel pipeline, as well as sheer budgetary constraints.

Trilateral Maritime Patrols

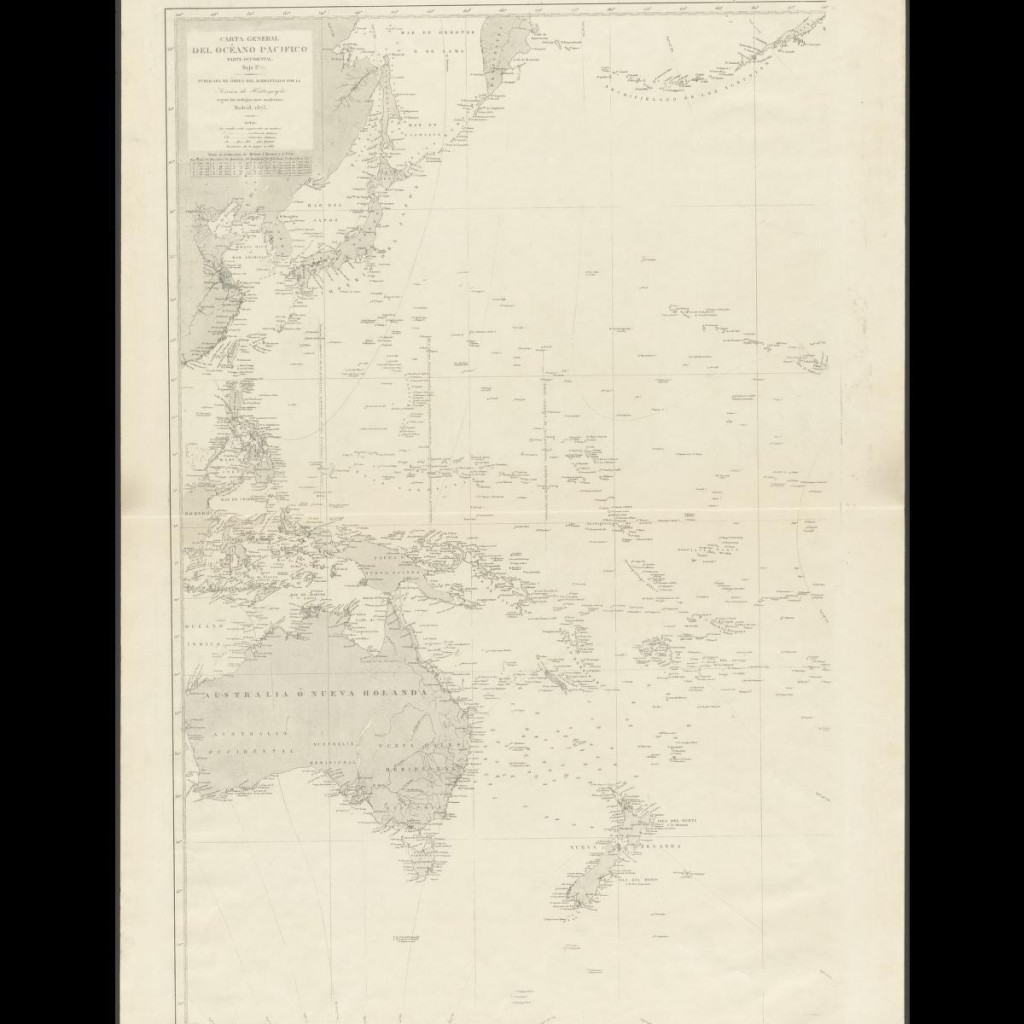

The trilateral maritime patrols that commenced in 2017 are far short of their potential, yet they have worked. The data is very clear: since the patrols began maritime incidents have declined. And while the improved situation is not irreversible, other scholars haver agreed with this assessment. And in addition to naval and coast guard coordination, Malaysia and the Philippines established a maritime policing agreement in 2017. In July 2017, the three states augmented the trilateral maritime agreement, with a trilateral air patrol agreement.

But by focusing limited resources on protecting key channels, they are leaving a lot of open ocean un-patrolled. While that might be fine for countering piracy, maritime kidnappings, and protecting regional shipping it has a downside for illicit smuggling and infiltrating terror suspects in and out of the Philippines.

There is still not a single place where the patrols are coordinated, and there is no fusion center such as what exists in Singapore’s Changi naval base. This coordination problem remains an issue of pride and sovereignty, where every state agrees to it in theory, but as long as they get to run it. But no state has the resources dedicated to make this effective. And they have been unwilling to take funding that Singapore or other outside partners (the United States and Australia) have offered. None of the states want to broaden this to be a multilateral force. Suggestions to shelve the sovereignty issue by basing it in a neutral third party, such as Brunei, have gone nowhere. Nonetheless, the Changi Fusion Centre in Singapore has greatly expanded its monitoring and reporting capabilities. Indeed, more information from the Sulu Sea region is being shared with them by both states as well as the shipping and fishing companies.

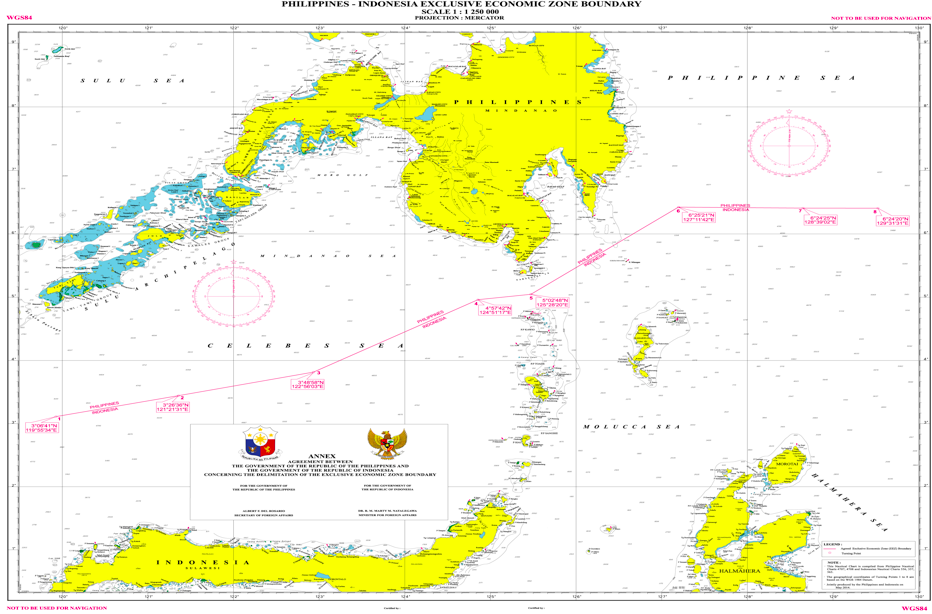

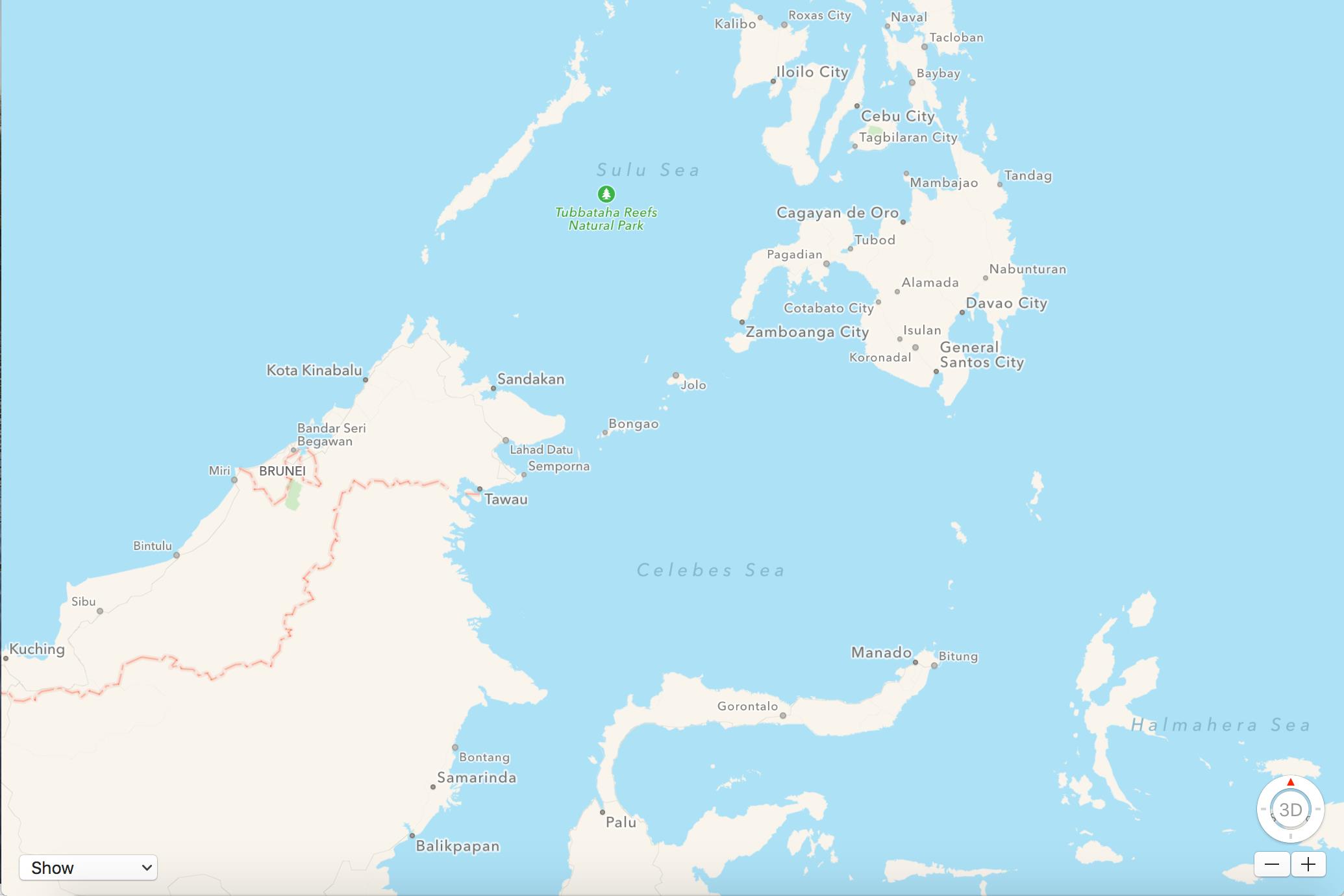

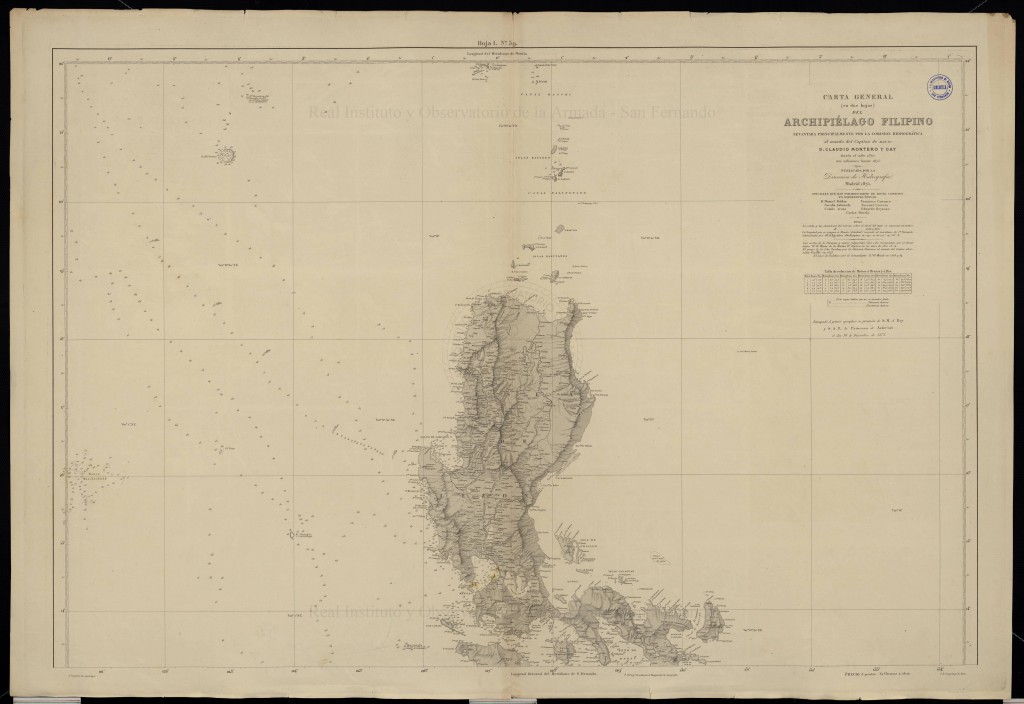

The lack of clear demarcated maritime borders that the author originally assumed would be a major impediment to the trilateral patrols has not borne out. The Philippines and Indonesia demarcated their 1,162 kilometer maritime boundary in the Celebes Sea in 2014, which came into effect in 2019. Malaysia and Indonesia still do not have a maritime border between Sabah and East Kalimantan, though there have not been any major flareups in the past few years. Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte reiterated his country’s claim to Sabah (still on the books, but long shelved) in 2016.2 The Malaysian government refused to discuss the issue with the Philippines, and maritime cooperation has continued.

It is a mere 15 minutes by fast boat between Lahud Datu and Tawi Tawi, so a clearly demarcated border, at least a de facto one, is important. At the very least, the countries have not let ongoing legal disputes interfere with maritime policing operations. Indeed, Indonesia and Malaysia were able to wrest the right of hot pursuit, a major concession, from the Philippines, after threatening unilateral military action.

The Malaysian security forces have maintained a very active defense posture on the water. They have not been shy about using force, and in 2018 thwarted ten attempted incursions, and killed nine suspected kidnappers, including four in a well-publicized incident in April.

No doubt, each country has increased their maritime capabilities, but they are still dwarfed by their land-based counterparts. In all three nations the army’s budget remains larger than the navy and air force’s combined. Indonesia’s attempts to stand up their Coast Guard continues to fall short. None of the three countries has maritime capabilities in proportion with their security needs or coastlines. And yet, even a small degree of coordinated patrols and additional resources has been a relatively effective deterrent.

Conclusion

No Malaysian security official that the author interviewed saw any significant improvements in the security situation in the Southern Philippines, and especially throughout Sulu and Tawi Tawi. Despite bilateral pledges of cooperation in counterterrorism, they expect incursions, maritime kidnappings and ship-jackings to continue. And since they have little confidence in Philippine authorities, they know that the onus was on them to enhance security and deter incursions.

And yet, there is real concern that this over time will be a money pit that Malaysia simply cannot afford. As one Malaysian security analyst put it: “They don’t have an endgame [in Sabah]. Tell me how this ends?”

Zachary Abuza, PhD, is a Professor at the National War College where he specializes in Southeast Asian security issues. The views expressed here are his own, and not the views of the Department of Defense or National War College. Follow him on Twitter@ZachAbuza.

Endnotes

1. The author maintains an open-source data set on southern Philippine security incidents by non-state actors. As it is based on media reporting, it tends to be conservative, as many incidents do not get reported on.

2. The Philippines claims that Sabah was patent of the Sultanate of Sulu, which leased the land to the North Borneo Company, a British royal concession in 1878. The British claim that the land was ceded. In 1963, Sabahans voted in a referendum to join Malaya (along with Singapore and Sarawak), creating Malaysia. The Philippines has maintained the claim, though it has largely been dormant, until President Duterte’s 2016 statement.

Featured Image: Philippine government soldiers fighting the Maute group watch a helicopter attack (not pictured) as they take a break inside a military camp in Marawi City, southern Philippines May 30, 2017. (REUTERS/Erik De Castro)