Guest post for Chinese Military Strategy Week by Eric Gomez

History has shown that emerging great powers and established or declining great powers are likely to fight major wars in order to determine the balance of power in the international system. There is considerable fear that the U.S. and China are heading towards great power conflict. As Christopher Layne argues, there are “several important — and unsettling — parallels between the Anglo-Germany relationship during the run-up to 1914 and the unfolding Sino-American relationship.” The headline-grabbing dispute in the South China Sea offers an excellent example of one of the several flashpoints that could spark a larger conflict between the U.S. and China. But the probability of great power conflict between the U.S. and China can be reduced if the two states can find ways to better manage interactions in flashpoint areas.

The oldest flashpoint, and the area most important for Chinese domestic politics, is the Taiwan Strait. In 1972, the Shanghai Communique stated that the so-called Taiwan question was the most important issue blocking the normalization of relations between the U.S. and China. This question has yet to be solved, mostly because Taiwan has been able to deter attack through a strong indigenous defense capability backed up by American commitment.

The status quo in the Taiwan Strait will be unsustainable as China continues to improve its military capabilities and adopt more aggressive military strategies. If the U.S. wants to avert a war with China in the Taiwan Strait, it must start looking for an alternative to the status quo. Taiwan’s strategy of economic accommodation with China under the Ma Ying-jeou administration has brought about benefits. The U.S. should encourage Taiwan to deepen its military and political accommodation with China. This would be a difficult pill for Taiwan to swallow, but it could offer the most sustainable deterrent to armed conflict in the Taiwan Strait.

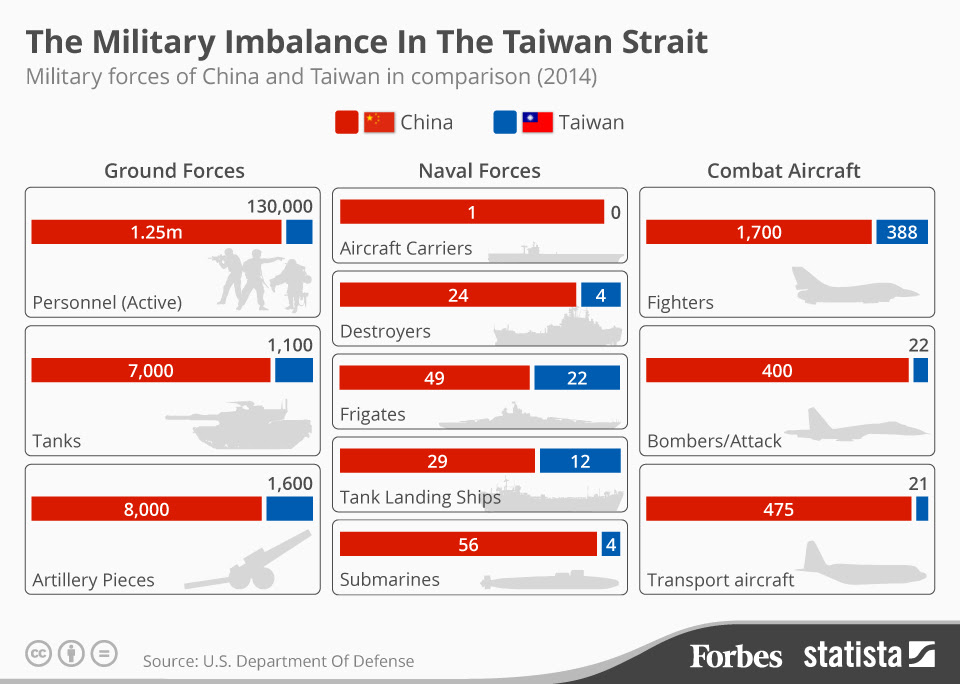

For years, Taiwan’s de facto independence from China has relied on a qualitatively superior, defense-focused military that could prevent the landing of a large Chinese force on the island. The growing power of the Chinese military, especially its naval and missile forces, has begun eroding this qualitative advantage. Indeed, some observers have already concluded that “the days when [Taiwan] forces had a quantitative and qualitative advantage over [China] are over.” Taiwan still possesses a formidable military and could inflict high costs on an attacking Chinese force, but ultimately American intervention would likely be necessary to save Taiwan from a determined Chinese attack.

Military intervention by the U.S. on the behalf of Taiwan would be met with formidable Chinese resistance. China’s anti-access/area denial strategy complicates the U.S.’s ability to project power in the Taiwan Strait. China’s latest maritime strategy document, released in May of this year, states that China’s navy will start shifting its focus further offshore to include open seas protection missions. Such a shift implies an aspirational capability to keep intervening American forces away from Taiwan. American political leaders have not given up on Taiwan, and the 2015 U.S. National Military Strategy places a premium on reassuring allies of America’s commitments. However, the fact that China’s improving military capabilities will make an American military intervention on behalf of Taiwan more and more costly must not be ignored.

The best option for preventing a war in the Taiwan Strait is deepening the strategy of accommodation that Beijing and Taipei have already started. According to Baohui Zhang, accommodation “relies on expanding common interests, institutionalizing dialogues, promoting security confidence-building and offering assurances to establish mutual trust.” The Ma Ying-jeou administration in Taiwan has tried to use accommodation as a way to lock in the status quo and avoid conflict, but their efforts have been met with more and more popular backlash in Taiwan. China’s military strategy document does acknowledge that “cross-Taiwan Straits relations have sustained a sound momentum of peaceful development, but the root cause of instability has not yet been removed.”

If Taiwan is serious about accommodation as a means of deterring military conflict, then it should cease purchasing military equipment from the U.S. Stopping the arms purchases would send a clear message to Beijing that Taiwan is interested in deeper accommodation. A halt in arms sales would also benefit U.S.-Chinese relations by removing a “major stumbling block for developing bilateral military-to-military ties.” This is certainly a very controversial proposal, and would likely be very difficult to sell to the Taiwanese people, but as I’ve already explained the status quo is becoming more and more untenable.

There are two important things to keep in mind about this proposal which mitigate fears that this is some kind of appeasement to China. First, halting U.S. arms sales does not mean that Taiwan’s self-defense forces would cease to exist. China may be gaining ground on Taiwan militarily, but the pain that Taiwan could inflict on an attacking force is still high. China may be able to defeat Taiwan in a conflict, but the losses its military would take to seize the island would significantly hamper its ability to use its military while it recovers from attacking Taiwan.

Second, there is an easily identifiable off-ramp that can be used by Taiwan if the policy is not successful. Stopping arms purchases is meant to be a way of testing the water. If the Chinese respond positively to the decision by offering greater military cooperation with Taiwan or some form of political concessions then Beijing signals its commitment to the accommodation process. On the other hand, if the Chinese refuse to follow through and meet Taiwan halfway then Beijing signals that it is not actually committed to accommodation. Taiwan would then resume purchasing American weapons with the knowledge that it must find some other way to prevent conflict.

Accommodation by giving up American arms sales is a tough pill for Taiwan to swallow, but it simply does not have many other viable alternatives to preventing conflict. Taiwan could pursue acquiring nuclear weapons, but this would be met by American opposition and would likely trigger a pre-emptive attack by China if the weapons program were discovered. Taiwan could try to avert conflict by increasing military spending to forestall, but this would be difficult to sustain so long as China’s economy and military spending is also growing. Analysts at CSBA have argued for deterrence through protraction, which advocates employing asymmetric guerrilla-style tactics to prevent China from achieving air and sea dominance. This has the highest likelihood of success of the three alternatives mentioned in this paragraph, but it still relies on intervention by outside powers to ultimately save the day.

Taiwan’s military deterrent will not be able to prevent a Chinese attempt to change the status quo by force for much longer. Any conflict in the Taiwan Strait would likely involve a commitment of U.S. forces and could lead to a major war between the U.S. and China. Accommodation could be the best worst option that Taiwan, and the U.S., has for preventing a war with China. Announcing an end to American weapons purchases could bring Taiwan progress on negotiations with China if successful while still providing off-ramps that Taiwan could take if unsuccessful. I admit, the idea of accommodation does have its flaws, and more work needs to be done to flesh out this idea. I hope that this idea of deep accommodation will add to the discussion about the management of the Taiwan Strait issue. The status quo won’t last forever, and a vigorous debate will be needed to arrive at the best possible solution.

Eric Gomez is an independent analyst and recent Master’s graduate of the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University. He is working to develop expertise in regional security issues and U.S. military strategy in East Asia, with a focus on China. He can be reached at gomez.wellesreport@gmail.com.