CIMSEC Topic Weeks have always been an excellent way to engage our community of defense and foreign policy professionals and academics to highlight issues that deserve greater attention. CIMSEC’s upcoming topic weeks will be listed well in advance in this post to give our prospective authors more lead time to develop their ideas and contribute superb publications. Expect subsequent announcements at the beginning of each month listing specific dates and deadlines for individual topic weeks.

Note: The schedule has been amended to accommodate the Distributed Lethality topic week in February.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

January: The Littoral Arena

Submissions due by Thursday, January 21.

Topic Week runs from Monday, January 25 to Sunday, January 31.

The littorals only constitute around 15 percent of the world’s oceanic expanse, yet 60 percent of the world’s urbanized populations are located within sixty miles of the coast, including 80 percent of the world’s capitals. The U.S. Navy has only recently drawn attention to the littoral domain after decades of emphasizing blue water sea control. What are the unique warfighting challenges posed by the littorals? What capabilities and operating concepts best enable power projection in this complex environment? Can navies optimized for blue water operations effectively translate their experience into the littorals?

February: Distributed Lethality

Submissions due by Sunday February 21

Topic Week runs from February 22-February 28.

The Distributed Lethality Task Force partnered with CIMSEC to launch a topic week exploring the concept and outlined various lines of inquiry the task force is interested in pursuing. Distributed Lethality is an initiative launched by Navy leadership to explore the warfighting benefits offered by dispersing surface combatants, employing them in new roles, and adding more firepower across the fleet.

March: Naval Humanitarian Assistance/Disaster Relief (HA/DR)

Time and time again, naval forces have performed admirably as first responders to devastating natural disasters. Naval forces can rapidly maneuver to disaster struck areas and facilitate the transfer of millions of pounds of critical supplies in a matter of weeks. The Asia-Pacific is especially prone, with over half a million lives lost and $500 billion in damages incurred within the last decade due to natural disasters. Can HA/DR operations refine warfighting skills? What are the political challenges and benefits of deploying naval forces in support of humanitarian operations? Could demand for naval aid increase as sea levels risen and climate change progresses?

April: Sino-Indo Strategic Rivalry

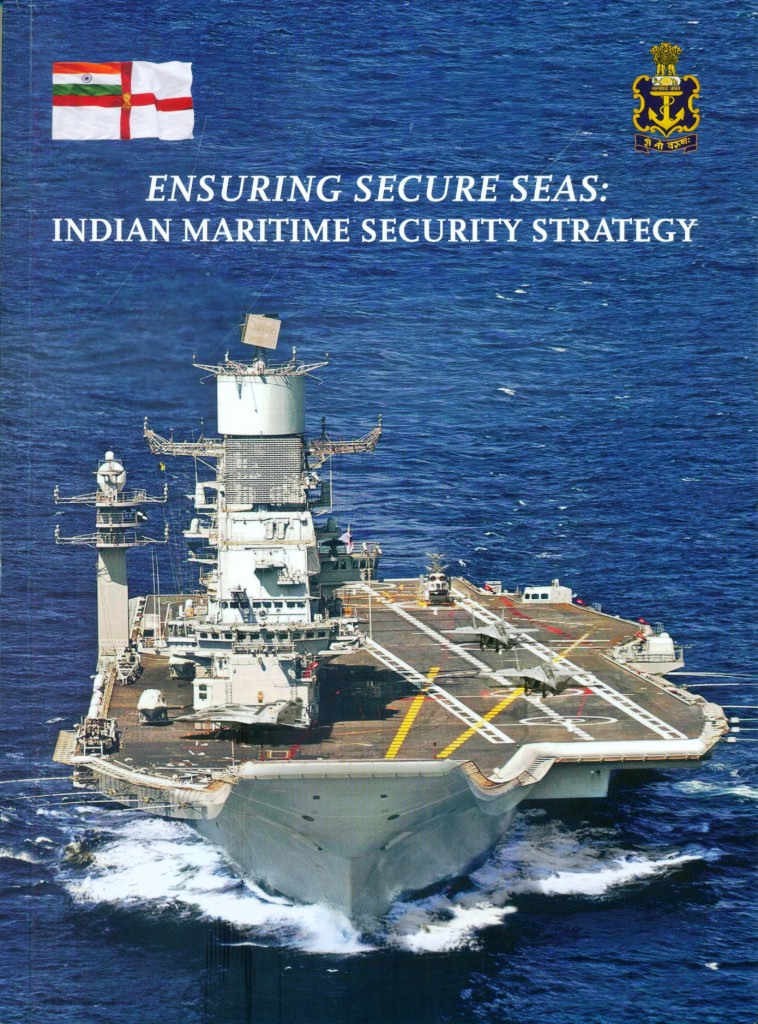

Much has been made of great power competition in the Asia-Pacific, with the U.S. and China considered the main actors, but India is a powerhouse in the making. India’s rapidly growing economy and modernizing armed forces ensures its relevance in the Asia-Pacific. Prime Minister Modi aligned India with U.S. policy towards South China Sea maritime disputes with a joint statement stating “We affirm the importance of safeguarding maritime security and ensuring freedom of navigation and over flight throughout the region…” Additionally, the Indian peninsula juts 1000 km into the Indian ocean, providing India’s carrier equipped navy superb positioning to affect sea lines of communication flowing towards the straits of Malacca. How might this strategic rivalry evolve, and is there precedent and potential for conflict?

Authors can send get in touch with the editorial team and send their submissions to Nextwar@cimsec.org. Topic weeks are competitive and not all submissions may be accepted, so we encourage thoroughly researched contributions. CIMSEC topic weeks are our opportunity to make our mark as a community on the big discussions, and we look forward to promoting your insights.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. Follow us @CIMSEC.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]