By Tuan N. Pham

Part 1 of this two-part series outlined a conceptual framework for characterizing the dynamics that contribute to instability and stability in the space domain. It made the case that instability arises when there is a real or perceived lack of order and security with the worst possible outcome being the “Thucydides Trap” – a rising power opposes a dominant power leading to a great power competition for space preeminence. On the flip side, it also made the case that stability arises when there is a real or perceived sense of order and security with the best possible outcome being the universal acceptance that “space is big enough for everyone and it is in everyone’s best interest to keep it free for exploration and use by all.” With this backdrop, Part 2 will focus on the ways and means the United States can employ to reduce instability and reinforce stability in the space domain while maintaining space preeminence into the 21st century.

U.S. Space Stability Challenges

Preeminence Puzzle. As the guarantor of the global economy and provider of security, stability, and leadership because of its powerful military and vast network of allies and partners, the United States delivers global public goods that others cannot. A case in point is the current volatility of the South China Sea. Without the stabilizing presence of the U.S. Navy operating on the high seas there, Chinese assertiveness and unilateralism could destabilize the region, damaging both regional and global commerce and possibly leading to an unwanted conflict. Thus, there is a strong need going forward for a comparable guarantor of the freedom of space (a net provider of space security) to ensure the free flow of space commerce, a leadership role that calls out to the United States, supported by allies and partners, to fill.

Just as maritime preeminence is necessary to guarantee the freedom of the seas, so too is space preeminence needed to guarantee the freedom of space. By committing to space preeminence, America will better protect its critical strengths in space; enhance its space deterrence posture by being able to impose larger costs, deny greater benefits, and encourage more restraint; prolong its terrestrial preeminence; and reverse the growing perception of American decline.

Decline is a deliberate choice, not an inevitable reality. Having complementary policies and strategies in contested domains fosters unity of effort, optimizes resource allocation, sends a strong deterrent message to potential adversaries, and reassures allies and partners. To do otherwise invites strategic misalignment and miscommunication and encourages potential competitors to further advance their counter-balancing efforts. Put simply, if the United States does not preserve its current strategic advantages in space, a rising power like China may gradually eclipse America as the preeminent power in space which will have cascading strategic ramifications on earth.

This greater role will demand more analysis and planning to address the anticipated challenges of domestic fiscal constraints; emerging and resurgent space powers; potentially destabilizing space competition; escalation control; and establishing and maintaining partnerships for collective space security through risk sharing and burden sharing – similar to the challenges now facing the U.S. rebalance to the Indo-Asia-Pacific. The puzzle for American policymakers is whether it may be more cost-effective to invest now and maintain the current strategic advantage in space or pay more later to make up for diminished space capabilities and capacities while accepting greater strategic risk in the interim.

Domain Dilemma. America fundamentally has two space deterrent and response options – (1) threaten to respond in the same domain; (2) threaten cross-domain retaliation to underwrite the deterrence of attacks on U.S. space capabilities. The former represents a vertical escalation if the response is disproportionate to the attack, and possibly “some” horizontal escalation depending on the target sets. This could result in large amounts of space debris and the resetting of international norms of behavior by legitimizing space attacks. The latter option represents a vertical escalation if the response is “perceived” as disproportionate to the attack, and horizontal escalation respective to the other domains. Nonetheless, the scope, nature, and degree of action must ultimately strike the delicate balance between the need to demonstrate the willingness to escalate and the imperative to not provoke further escalation in order to maintain space stability. The dilemma for the United States is where, when, and how best to deter; and if deterrence fails, where, when, and how best to respond.

Reliance/Resilience Riddle. Enhancing and securing space-enabled information services (SEIS) is now essential to U.S. national security, a daunting task considering that space has become more and more “congested, contested, and competitive” and less permissive for the United States. Therefore, the current strategic guidance – 2010 National Space Policy (NSP), 2011 National Security Space Strategy (NSSS), and 2012 DoD Space Policy (DSP) – directs the U.S. government to reduce the nation’s disproportionate reliance on space capabilities and the vulnerability of its high-value space assets through partnerships and resiliency, respectively. The riddle for America is how best to manage the dichotomy between reliance and vulnerability through resilience.

Offensive Counter-Space (OCS) Conundrum. Space warfare is intrinsically offense-inclined due to the uncertainty, vulnerability, predictability, and fragility of space assets; and ever-increasing OCS capabilities to deceive, disrupt, deny, degrade, or destroy space systems. The latter can be destabilizing (warfighting capability) or stabilizing (deterrence) depending on one’s perspective. Hence, the conundrum for the United States is not whether or not to possess OCS capabilities – but how best to use them to deter and retaliate if deterrence fails; what type, how much, and to what extent should they be publicly disclosed; and how to leverage the existing international legal framework and accepted norms of behavior to manage them without constraining or hindering one’s own freedom of action.

Moreover, OCS capabilities continue to grow in number and sophistication driven by the “offense-offense” and “defense-offense” competition spirals influencing military space policies in Washington, Beijing, Moscow, and elsewhere. OCS developments to defeat defensive counter-space (DCS) measures drive further OCS developments for fear of falling behind in offensive capabilities and encouraging a first strike by an adversary, while DCS developments to mitigate OCS measures further drive OCS developments to remain viable as deterrent and offensive tools.

Refining Military Space Capability

Develop Cross-Domain Deterrence Options. Deterrence across the interconnected domains may offer the best opportunity to deter attacks on U.S. space capabilities, and if deterrence fails, retaliate across domains to deter further attacks. Prudence then suggests the need for some level of active planning prior to the onset of increased tensions and hostilities. American policymakers and defense planners should have on hand a broad set of potential cross-domain responses to the threats of space attack or the space attack itself. The responses should be organized by the levels of force application, provocation, and risk; dynamic enough to accommodate the ever-changing strategic, operational, and tactical conditions; and part of a larger menu of policy options to better manage tensions and escalation during pre-hostilities and identify off-ramps during hostilities. On balance, the decision on whether or not, when, and how to implement these responses should be viewed through the lens of cost and risk imposition, proportionality, strategic policy coherence, and desired outcome.

Continue to Increase Resiliency. Strengthening the resiliency of the U.S. national security space architecture may offset the offensive inclination of space warfare by lessening the vulnerability and fragility of space assets, assuring retaliatory capabilities, and denying benefits of OCS operations.

Building up space protection capabilities will decrease the vulnerability and fragility of high-value space assets by presenting more targets (disaggregated space operations, micro-satellites), hiding targets (signature reduction), maneuvering targets (dynamic orbital profiles for unpredictability and threat avoidance), hardening targets (strengthened space assets and networks against kinetic and non-kinetic attacks), and complicating targets (hosted payloads on commercial, civil, and allied or partnered nations satellites).

Mission assurance can be sustained by responsive launch capabilities (launch-on-demand services for rapid reconstitution of degraded or lost space capabilities), Operationally Responsive Space (ORS) program (mass production of microsatellites in a short period of time), and “sleeper” orbiting satellites (standby spares that will activate when needed).

Mission continuity in a degraded, disrupted, or denied space environment can be ensured by the following measures: developing standard operating procedures for continuity of operations; hosting some SEIS in commercial, civil, and allied or partnered space systems as part of a surge in space capability and as a measure of redundancy; building and sustaining alternative terrestrial-based systems to reduce SEIS reliance – chip-scale combinatorial atomic navigator for precision, navigation, and timing services; high-altitude long-endurance unmanned aerial systems for persistent ISR; and fiber-optic cabling and terrestrial radio and microwave communications devices for secured C2.

Continue to Invest in OCS Capabilities. The heart of the matter remains what type of OCS capabilities (reversible, irreversible, or both) and how much. Regarding the latter, some argue none or limited quantities are required while others call for robust OCS capabilities. Whatever the right answer may be, it is difficult to see how one can deter or retaliate if deterrence fails without “some” OCS capabilities, especially considering that potential competitors like China and Russia are actively developing their own OCS capabilities to challenge U.S. space preeminence, and by extension, terrestrial preeminence.

Strengthening Space Governance

Since the elimination of OCS capabilities is unlikely, attention and effort should be placed on managing them instead. The extant international legal framework and accepted norms of behavior offer some ways and means to reduce OCS capabilities to a manageable level, restrict their proliferation, and establish constraints and restraints on their employment. The space powers should review the existing international agreements and legal principles, and determine what additional conventions or provisions are needed. Goals can be to set acceptable limits of OCS capabilities; renounce the first-use of OCS; establish confidence-building measures; and limit the possession of OCS capabilities to select space powers and out of the hands of “pariah” states (North Korea and Iran) and undesirable non-state actors (terrorist, criminal, and business groups).

Space powers should also review and update current treaties and legal principles to govern the changing strategic, operational, and tactical landscapes, particularly those overseeing activities in space, registration of space objects, and space sovereignty. States should negotiate new treaties to manage emerging space challenges like space debris, RF interference, and other space threats. Finally, parties must develop new capabilities and protocols for verifying treaty compliance and enforcement.

The international community should seek to empower the United Nations (UN) governance of space and space activities, particularly in the areas of regulation, arbitration, and collaboration. The UN should consider further defining and codifying the rights and responsibilities of nation-states with respect to their activities in space through a UN Convention on the Law of Space (similar to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea); establishing the International Space Authority (similar to the International Seabed Authority) for the regulation of space-based resources; and forming the International Tribunal for the Law of Space (similar to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea) for arbitration of space-related disputes. Transform the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs into an empowered World Space Council to promote international collaboration in space, manage emerging space challenges, and act as a forum for global contingency planning and preparedness for potential space threats.

Expand Partnerships. The 2010 NSP, 2011 NSSS, and 2012 DSP call for building enduring partnerships with other space-faring nations, civil space organizations, and commercial space entities to share benefits, costs, and risks; strengthen extant alliances through increased cooperation across the various space sectors; spread SEIS reliance to others; and provide greater space deterrence and stability through collective defense. That being said, partnerships also carry with them risks and concerns. Risks include the unpredictability of horizontal escalation (attack on U.S. space assets with hosted payloads involves other parties) and greater potential damages and unintended consequences (more interdependent players and things that can go wrong). Concerns center around autonomy (transparency, response, and responsiveness constrained by other parties), operational security (information sharing, technology transfer, and increased risk of insider threat), legality (intellectual property rights, loss compensation, and sovereignty), and the interoperability of disparate space systems (varying levels of sophistication amongst partners). All things considered, the benefits outweigh the risks, and concerns are manageable in varying degrees.

Partners should build on extant bilateral/multilateral partnerships to complement and supplement U.S. space capabilities. They must leverage emerging opportunities like the Memorandum of Understanding between the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, and Australia for joint space operations and Japan’s plans to develop a military space force by 2019. These partnerships may vary in nature, scope, and extent depending on the strategic and operational imperatives, costs, risks, and domestic legal constraints; and could involve capacity building, information sharing, technology transfer, interoperability, integration, and joint operations.

Partners should promote international collaboration and foster shared reliance on space-enabled capabilities in the fields of scientific exploration (International Space Station, interplanetary probes, and manned space flights), commercial ventures (launch vehicles, micro-satellites, space tourism, and space mining), global positioning system or GPS interoperability (United States, Russia, European Union, and China), shared space situational awareness or SSA (Space Fence and Geosynchronous SSA Program), space-based observations (climate change, weather, and humanitarian assistance/disaster relief), space debris, and asteroid defense.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, space stability occurs when there is universal acceptance that “space is big enough for everyone and it is in everyone’s best interest to keep it free for exploration and use by all.” Moving forward, there is a common interest in safeguarding the collective need for guaranteed freedom of space under the imperative for all space-faring nations to support an international framework that encourages cooperation and manages competition in the space domain.

Tuan N. Pham is widely published in national security affairs. The views expressed are his own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government

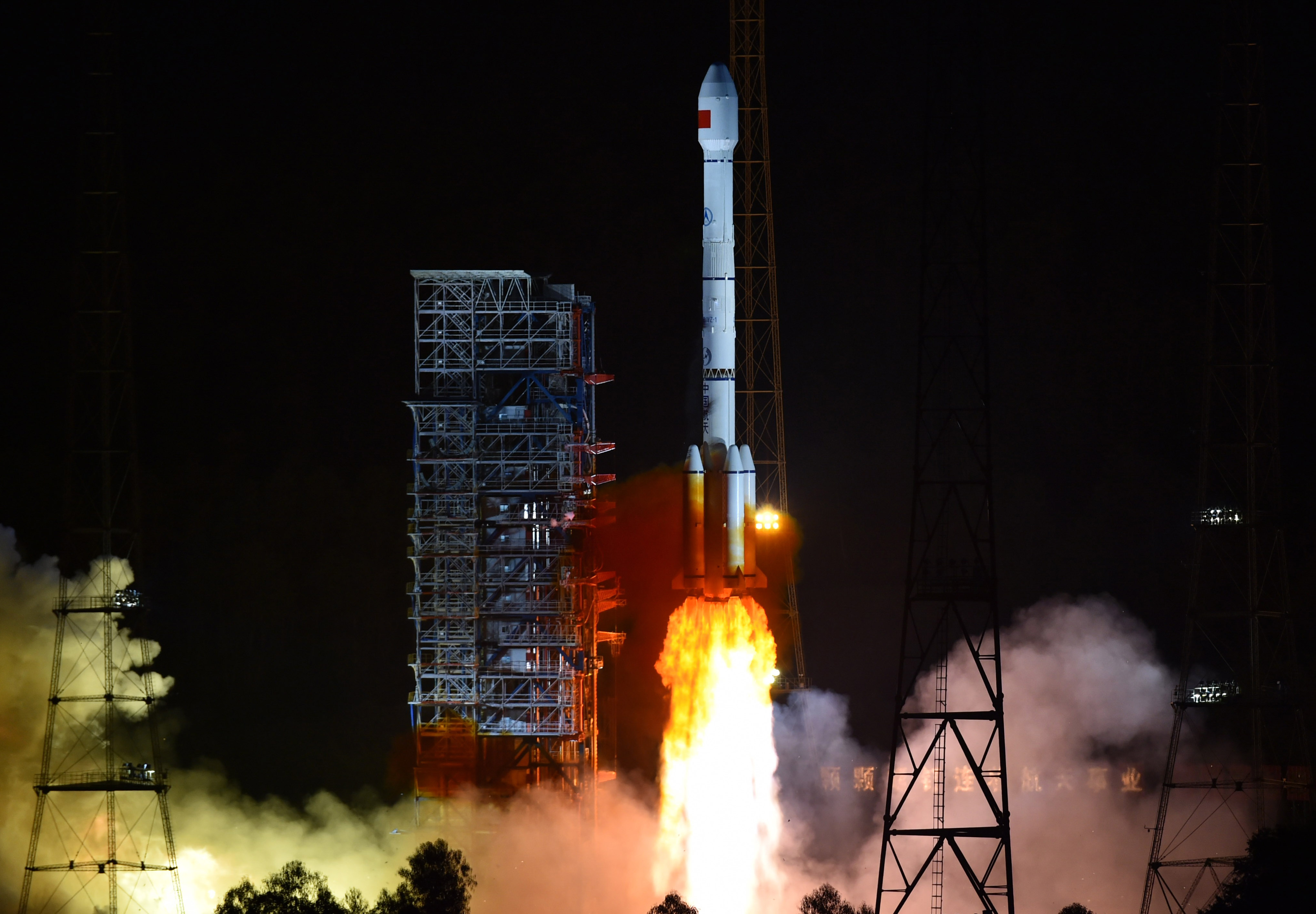

Featured Image: Launch of Russian military satellite (Russian Ministry of Defense)