The following article was originally featured by the National Maritime Foundation and is republished with permission. Read it in its original form here.

By Gurpreet S. Khurana

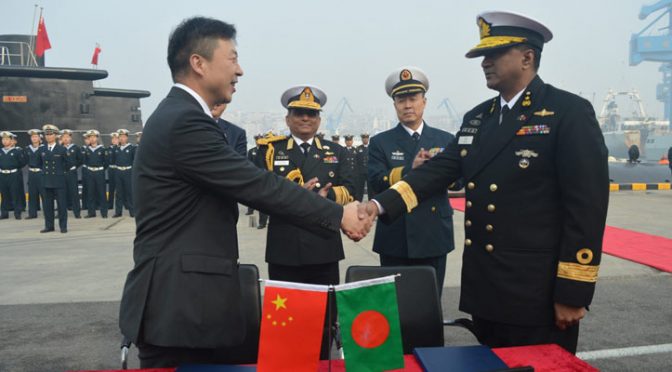

On 14 November 2016, the Bangladesh Navy (BN) took delivery of two old refurbished Chinese Type 035G Ming-class diesel-electric submarines. As part of the US$ 203 million contract signed in 2013, the submarines were handed over to the BN crew during a ceremony at the Liao Nan Shipyard in China’s Dalian city. The submarines are slated to be commissioned as Bangladesh Naval Ships (BNS) Nabajatra and Joyjatra and are expected to arrive in early 2017 at the new Bangladeshi submarine base being constructed near Kutubdia Island.

This may be a rather seminal development with strong ramifications not only for the littoral countries of the Bay of Bengal, but also for the wider Indo-Pacific region. This essay seeks to undertake an assessment of this development in the context of the likely imperatives of Bangladesh, the intentions of China, and its implications with specific reference to the Indian context.

Imperatives for Bangladesh

For any navy, the surface warships and their integral aircraft are capable of being used across the entire spectrum of conflict including for ‘constabulary’ and ‘benign’ missions ranging from counter-piracy to maritime search and rescue (M-SAR). In contrast, submarine forces – due to their inherent stealth characteristics – are optimized for sea-denial during war. Even in peacetime, these underwater platforms are used to undertake highly specialized missions against a military adversary like clandestine surveillance, intelligence-gathering, and Special Forces operations. Hence, it is difficult to fathom why Bangladesh – which does not encounter any conventional maritime-military threat – has inducted submarines into its navy. The maritime disputes between Bangladesh and two of its only maritime neighbors – Myanmar and India – were resolved through international arbitration in 2012 and 2014 respectively. Neither Naypyidaw nor New Delhi have indicated any reservations to the verdict of the international tribunals, nor have any other major outstanding contention with Dhaka.

It is nonetheless well known that the BN has since long aspired for a three-dimensional navy through inclusion of underwater warfare platforms. After Dhaka succeeded in settling its maritime boundary through the highly favorable decisions of the international tribunals, the apex political leadership showered much attention upon the BN as the guardian of the country’s newfound maritime interests. Notably, Bangladesh is seeking an increasing dependence upon sea-based resources for economic prosperity of its rather high density of population. The political nod to acquire submarines may therefore be seen as an incentive for the BN. Besides, it is a low-cost deal to reinforce strategic ties with China, including by taking forward Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s support to President Xi Jinping for its ‘One Belt One Road’ (OBOR) initiative. Hence, the development seems to have been driven by symbolism for Bangladesh, rather than being a result of the navy’s appreciation-based force-planning based on an objective assessment of the projected security environment.

China’s Intentions

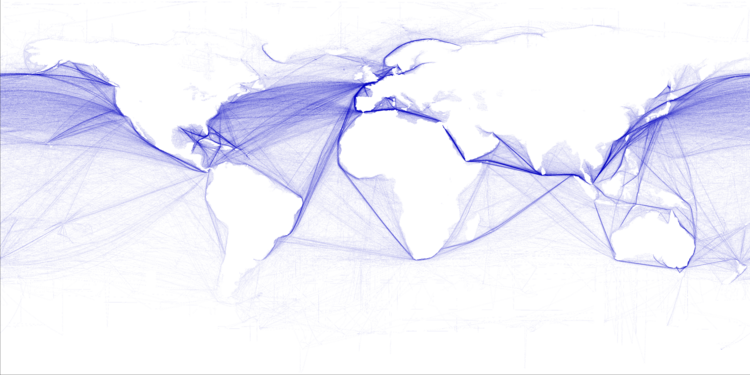

As in case of other defense hardware exports, Beijing’s overarching intent behind the sale of submarines would be to go beyond strengthening political ties with Dhaka, to bring about its ‘strategic dependence’ upon China. The long-term submarine training and maintenance needs of the BN would also enable China’s military presence in the Bay of Bengal, and enable it to collate sensitive data for PLA Navy submarine operations in the future. This area is becoming increasingly important as the transit route for China’s strategic crude-oil and gas imports, and bears the origin of China’s oil pipeline across Myanmar. Strategic presence in the area is also critically necessary for Beijing to supplement the strategic and geopolitical dimension of its Maritime Silk Road (MSR) plans.

Further, by selling the two old (though upgraded) Ming-class submarines – which were commissioned in early 1990s and presently at the end of their service life with the PLA Navy – Beijing has assiduously generated useful revenue out of hardware, which would have only ‘scrap value’ in a few years. As per an established practice in China, a significant proportion of the revenue would go to PLA Navy since the submarines were sourced from its inventory.

Implications

The sale of Chinese submarines to Bangladesh bears significant ramifications for the Indo-Pacific region. Lately, apprehensions are being increasingly expressed over the rapidly increasing number of submarines being operated by regional countries. An addition of a submarine-operating country would not only multiply the complexity of water-space management – particularly due to the confidentiality associated with the deployments of such stealth platforms – but could also lead other countries to follow suit. The development also strengthens the imperative for Indian Ocean navies to institute a mechanism for de-conflicting unintended naval encounters at sea through the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS), which ironically, is presently being chaired by Bangladesh.

The submarine sale to Bangladesh has come at a rather inopportune time for the countries of the Bay of Bengal. With the two major maritime disputes having been resolved, the sub-region was looking forward to enhanced maritime cooperation in various sectors like trade connectivity, blue economy, and maritime safety and security, including through the revitalisation of the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC). The BN’s acquisition of submarines could lead to littoral countries reassessing their maritime security strategies and adopting a cautious approach to maritime cooperation.

In the Indian context, New Delhi has little reason to be threatened by Dhaka’s newly-acquired sea-denial capability. Nonetheless, Beijing’s likely intent needs to be factored in its national security calculus, particularly considering the imminence of China’s military-strategic presence in close proximity to India’s naval bases, including its nuclear submarine bastion. Evidently, India’s foreign policy vis-á-vis Bangladesh needs to be recalibrated. At the national-strategic level, India possesses insufficient financial and defence-industrial wherewithal to offset China’s overwhelming influence upon Bangladesh, but there is no dearth of other leverages. In such circumstances, New Delhi may need to graduate from its long-standing policy of ‘appeasing’ Dhaka to a ‘carrot and stick’ policy.

Captain Gurpreet S Khurana, PhD, is Executive Director at National Maritime Foundation (NMF), New Delhi. The views expressed are his own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the NMF, the Indian Navy, or the Government of India. He can be reached at [email protected].

Featured Image: Handover ceremony of two ex-PLA Navy Type 035 submarines to the Bangladesh Navy. (banglanews24.com)

influence of emerging naval platforms and technologies in the geostrategic contours of the Indo-Pacific region. It identifies relevant historical precedents, forming the basis for various maritime development and security related projects in the region.

influence of emerging naval platforms and technologies in the geostrategic contours of the Indo-Pacific region. It identifies relevant historical precedents, forming the basis for various maritime development and security related projects in the region.