By Jeffrey Kline, John Tanalega, Jeffrey Appleget, and Tom Lucas

Introduction

The paper is about synergy. It demonstrates the power of using analytical tools in a logical sequence to generate, develop, and assess new concepts and technologies in warfare. Individually there is nothing new here. Each of the analytical tools described in this paper is thoroughly discussed in academic literature. The use of intelligent experimental design and large scale simulation to advance knowledge in defense and homeland security issues is well describe in Design and Analysis of Experiments by leaders in the Naval Postgraduate School’s Simulation Experiments and Efficient Design (SEED) Center for Data Farming (Sanchez, 2012).1 The power of campaign analysis to gain insight and quantify the value of new technologies and capabilities is covered in the campaign analysis chapter of Wiley’s Encyclopedia of Operations Research and Management Science (Kline, 2010).2 Wargaming’s use to develop concepts for employment of those new technologies and discover possible risks to them are discussed recently in both the Military Operations Research Society’s Phalanx (Appleget, 2015)3 and the journal for Cyber Security and Information Systems Information Analysis Center (Appleget, 2016).4

It is the synergy created by bringing these tools together—linked by officers with tactical experience and educated in the analytical techniques—which this paper addresses. We provide it as an example of military operations research in practice to advance naval force development and fleet combat tactics. We tell this story through the lens of our co-author, LT John Tanagela, USN, and one technology, the Medium Displacement Unmanned Surface Vessel (MDUSV), but provide multiple examples of past work similar in nature. LT Tanagela is a qualified Surface Warfare Officer who chose to attend the Naval Postgraduate School to obtain a master’s degree in Operations Research. We select John’s educational and research experience not for its uniqueness, but instead for its normalcy as a NPS OR student with unrestricted line qualifications. Our other co-authors were John’s combat models instructor, campaign analysis instructor, wargaming instructor, and thesis research advisors. We provide descriptions and results from the analytical courses John leveraged to advance his research in employing a MDUSV and highlights from his thesis. We conclude with brief summaries of other concepts and technologies advanced in this manner.

Triad of Military Applied Courses

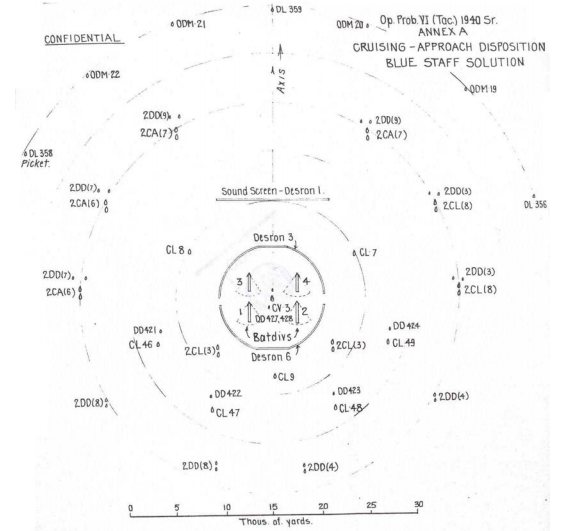

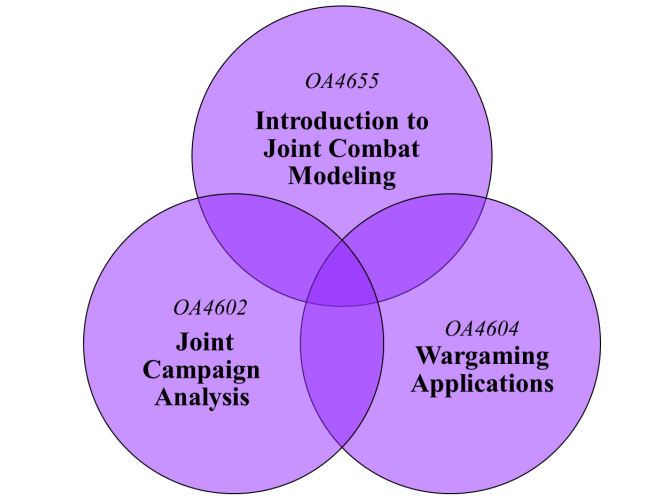

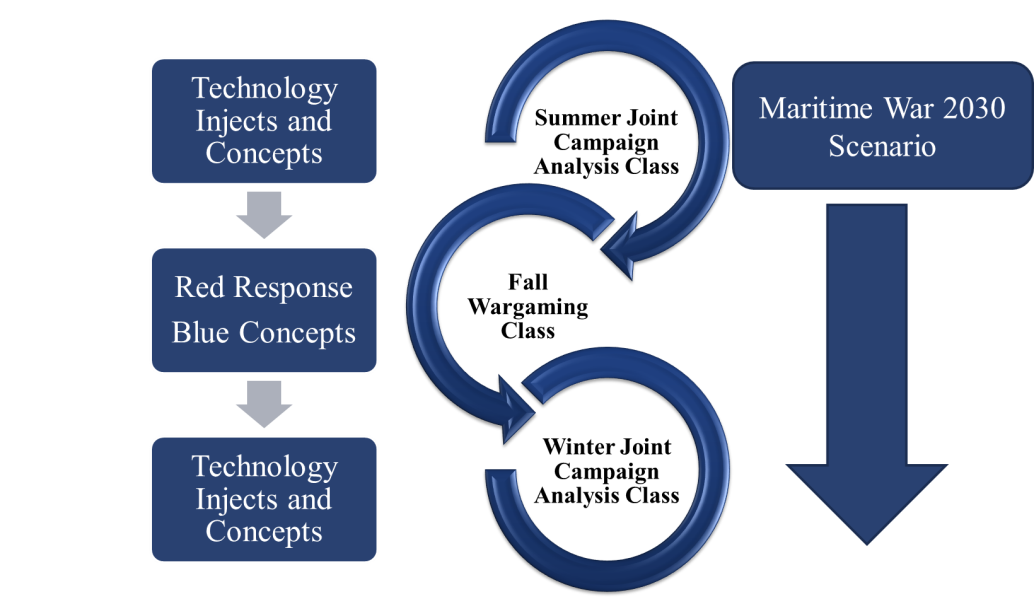

The Naval Postgraduate School’s Operations Research students receive three foundational courses in warfare analysis: the introduction to joint combat modeling course, the joint campaign analysis course, and the wargaming course (See Figure 1). In these applied courses they learn to model combat effects in tactical and operational level conflict, integrate these quantitative techniques in campaign analysis and human decision making, and, as a result, develop and quantitatively assess new concepts, tactics, and technologies.

The joint combat models course introduces traditional force-on-force modeling, including homogeneous and heterogeneous Lanchester equations, Hughes’ salvo equations, and computer-based combat simulations. It provides our officers the experience to integrate uncertainty into these models to allow for sensitivity analysis and design of experiments in exploring new capabilities.

The joint campaign analysis class leverages these new skills and previous course work in simulation, optimization, decision analysis, search theory, and probability theory by challenging our officers to apply them in a campaign-level scenario. During the course they must develop a concept of operation to meet campaign objectives, model that concept to assess risk using appropriate measures for their objective, and assess “new” technical capabilities by comparing them to their baseline concept analytical results. The results are quantitative military assessments of new concepts and technologies, identification of force capability gaps, and risk assessments (See Figure 2).

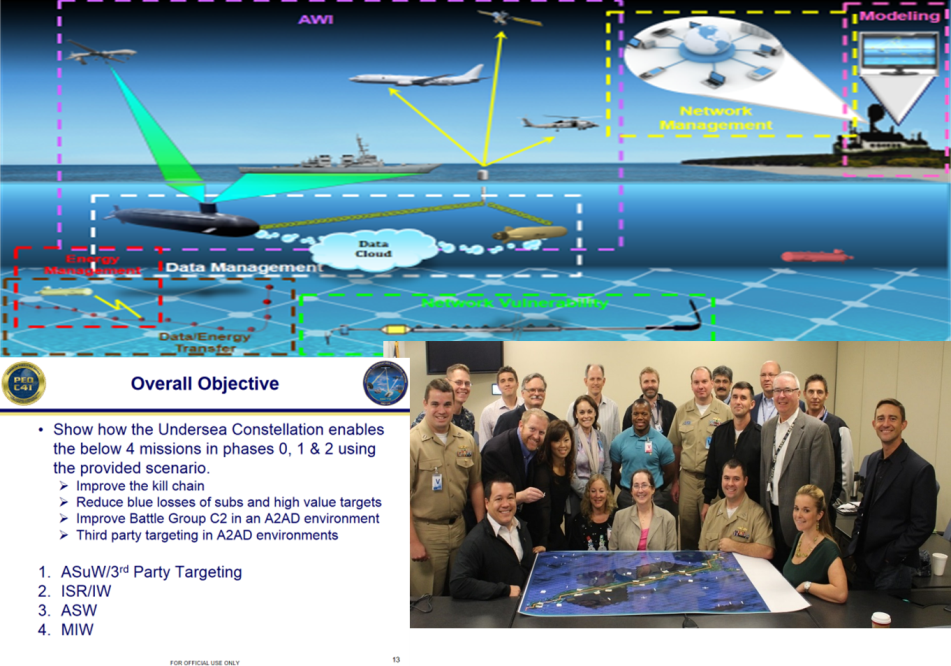

The wargaming class provides an overview of the history, uses, and types of wargaming, but focuses its efforts on teaching officers how to design, develop, execute, analyze, and report on an analytical wargame. After learning the fundamentals, officer-teams are assigned real-world sponsors who provide the objective and the issues they desire to address during a wargame. The officer-teams work with the sponsor through execution of an actual wargame, completing their course work by reporting the wargame’s analysis and results to the sponsor. An example is supporting the Navy’s PEO C4I by assessing the Undersea Constellation concept and technology. (See Figure 3)

Passing Lessons and Students along

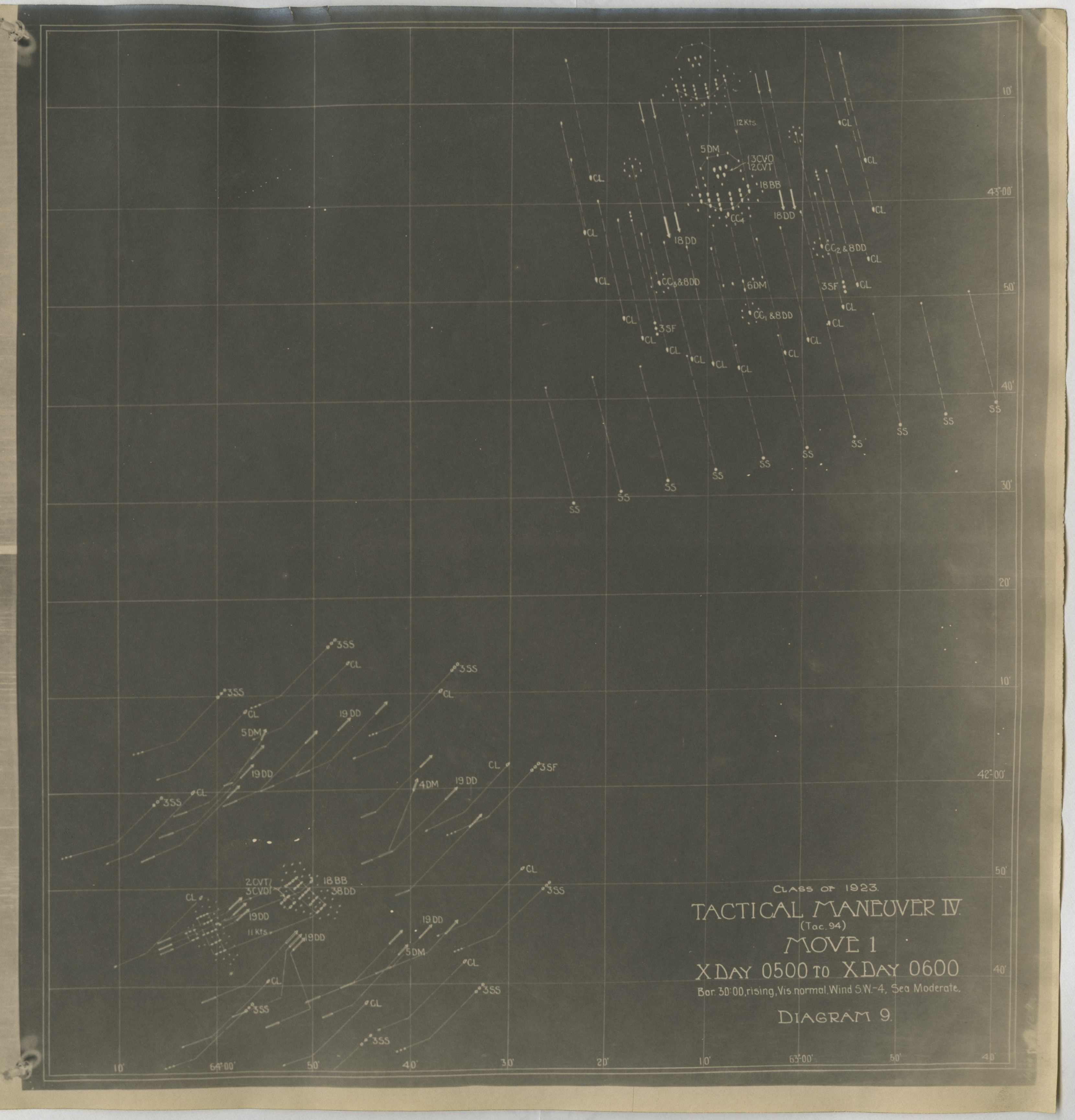

As the NPS operations research students proceed from one course to another in the triad above—where they are joined by Joint Operational Logistics students, Systems Engineering Analysis students, Defense Analysis students, and Undersea Warfare students—there is an opportunity to carry lessons from on course into another, and gain further insight into those concepts and technologies. The teaching faculty work closely to ensure that happens by design. NPS Warfare Analysis faculty and researchers use these courses synergistically to provide insights to real-world sponsors in advancing their concepts, assessing new technologies proposed by DoD labs and industry, and developing new tactics—all the while enhancing our officer-students’ educational experience and sharpening their combat skills. For example, after learning to model a war at sea strike using salvo equations in the joint combat modeling course, the officers are challenged to develop a maritime concept of employment using distributed forces in the joint campaign analysis class, and assess that concept using the salvo equations and simulation. That concept is passed to the wargaming class (usually the same students) to better understand Blue’s decisions in employing distributed forces and Red’s potential reactions. Common scenarios are used between classes with similar forces structures (See Figure 4).

The results of these capstone classroom efforts are a series of analytical and wargaming briefings, reports, and papers frequently shared with DoD and service organizations. In addition, the work informs other NPS research occurring in unmanned systems, networks, and command and control. Most impactful, however, is when officers are inspired to take a much more detailed look at new capabilities as their thesis research, using the insights gathered from their capstone course work as a foundation to build upon.

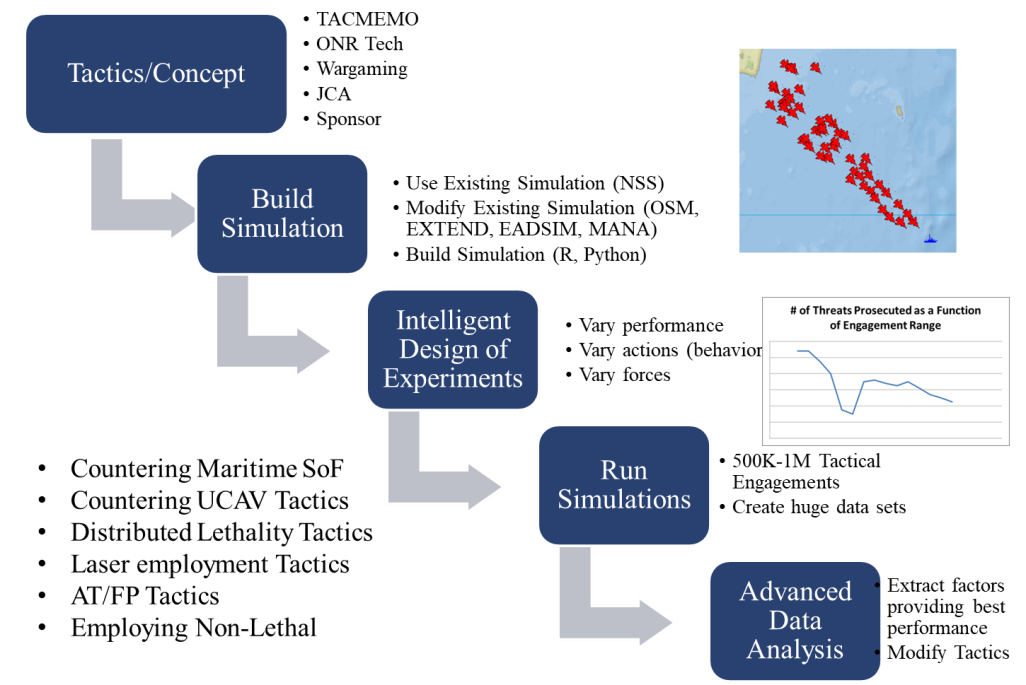

Simulating a Half Million Tactical Engagements

Officers frequently select a new technology explored in their military operations research applied courses to further study in their thesis work. They will draw upon their own operational experience to develop tactics to employ these technologies; work with weapon tactics instructors to refine these tactical situations; identify important variables and parameters within that scenario to further identify needed performance capabilities (range, speed, etc.) and tactical employment (formations, distances, logistics, etc.); build or use an existing simulation to model those tactics; use intelligent experimental design to efficiently explore a range of values for each of identified parameter; execute the experiment—frequently running over a half million tactical engagements; then use advanced data analytics to identify the most important parameters’ values to be successful (See Figure 5.)

These theses’ results are always of great value to warfare and tactics development commands, to resources sponsors, material commands, and defense laboratories developing new technologies. Their insights also inform future capstone course work and NPS technical research. We now turn to our specific example, LT John Tanalega and the Medium Displacement Unmanned Surface Vessel.

The Technology: The Medium Displacement Unmanned Surface Vessel

The Office of Naval Research (ONR) Medium Displacement Unmanned Surface Vessel (MDUSV) program is a self-deployed surface unmanned system capable of on station times of 60-90 days with ranges of 900-10000 nautical miles depending on speed (3-24 knots) and payload (5-20 tones).5 For the NPS warfare analysis group, we provide it the following future mission capabilities. In an antisubmarine warfare (ASW) role, it receives an off-board cue and hand off, then conducts overt trail with active sonar. It can act as an ASW scout in coordination with area ASW assets like the P-8 maritime patrol aircraft or benthic laid sensors in an Undersea Constellation, conducting large acoustic surveillance using passive and/or active bi-static sonar. It can deploy three Mk 54 or six smaller CRAW torpedoes. In its Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) role, it can work with surface ships as an advanced scout employing passive sensors, and in an offensive role, can carry eight RBS-15 surface-to-surface missiles. In its mine warfare role, it can conduct mine sweeping with a MK-104 acoustic sweep body or can deploy a clandestine delivered mine in an offensive mining role. It may also act as a forward environmental survey ship, a platform for operational military deception, a tow for a logistics barge, and special operations equipment delivery.

All MDUSVs in these analyses are augmented by TALON (Towed Airborne lift of naval systems)6, which can carry up to 150 pounds of payload up to 1,500 feet. This payload can be communication relays, radar, electronic jammers (or emitters for decoy operations), or optical sensors.

https://gfycat.com/AlivePitifulIberiannase

ACTUV conducting testing with TALONS (DARPA Video)

The MDUSV equipped with TALON has been introduced in several Joint Campaign Analysis classes and Wargaming classes as technical injects to be assessed. LT Tanalega was given the MDUSV as a technical inject for both these classes.

The Student: LT John Tanalega

Academically talented, John has a typical operational background for a Naval Postgraduate School Operations Research student. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 2011 with a Bachelor of Science degree in English. His initial sea tour was as Auxiliaries and Electrical Officer, and later First Lieutenant, in USS DEWEY (DDG 105). While assigned to DEWEY, he deployed to the Western Pacific, Arabian Gulf, Red Sea, and Eastern Mediterranean. His second division officer tour was as the Fire Control Officer in USS JOHN PAUL JONES (DDG 53), the U.S. Navy’s ballistic missile defense test ship. He attended the Naval Postgraduate School in from 2016 to 2018, where he earned a Master of Science degree in Operations Research and conducted his thesis research in tactical employment of the MDUSV.

Insights from the Joint Campaign Analysis classes, the Wargaming Classes, and other NPS research

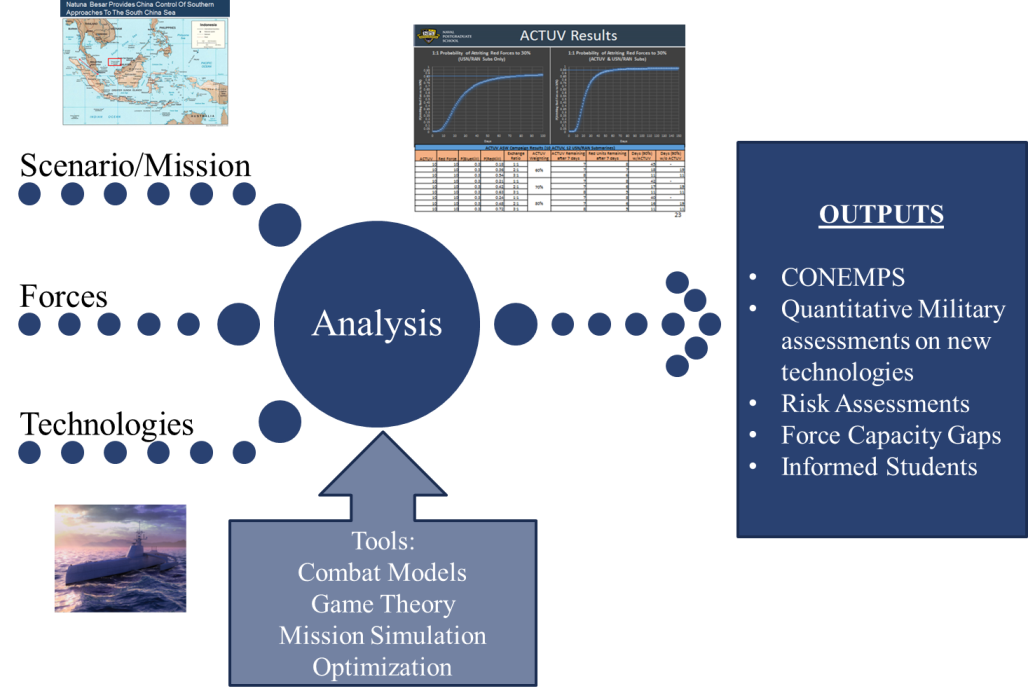

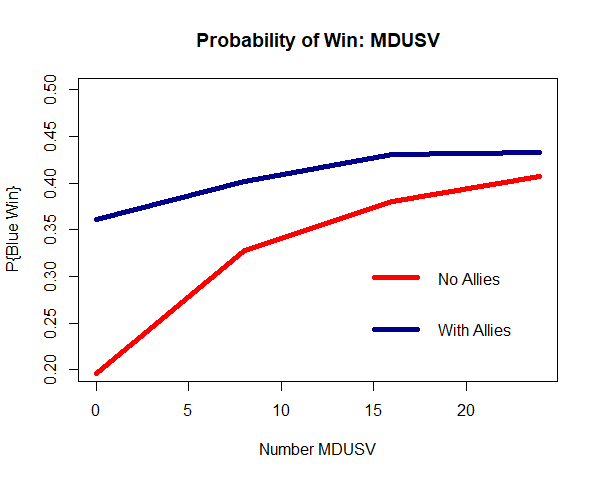

As mentioned, the MDUSV with TALON was introduced to a series of Joint Campaign Analysis classes and several NPS wargames. Officer-students have employed it in a variety of missions, from active operational deception to logistics delivery to riverine patrol. Its strongest characteristics are on-station time over unmanned aerial systems, sensor payload capacity over all other unmanned systems, and speed over unmanned underwater systems. Its limitations include vulnerability to attack (it has no active defense), which is mitigated by a low radar cross section making it difficult to target and/or acquire. Our analytical and wargaming teams have found their value forward in offensive naval formations and in defense screening formations (Figure 5). Employing a single or pair of MDUSV with a P-8 maritime patrol aircraft in an area ASW environment is also valuable. (Figure 6). Figure 5: The graph shows the probability of successfully finding and engaging an adversary’s amphibious task force in a South China Sea scenario with a traditional U.S. Surface Action Group (SAG) with and without allied ship support. As MDUSVs are added to the SAG, the probability of mission success is increased. The MDUSV are contributing to the ISR and targeting capabilities of the SAG. This analysis was produced using combat modeling by a Joint Campaign Analysis class team.

Figure 5: The graph shows the probability of successfully finding and engaging an adversary’s amphibious task force in a South China Sea scenario with a traditional U.S. Surface Action Group (SAG) with and without allied ship support. As MDUSVs are added to the SAG, the probability of mission success is increased. The MDUSV are contributing to the ISR and targeting capabilities of the SAG. This analysis was produced using combat modeling by a Joint Campaign Analysis class team.

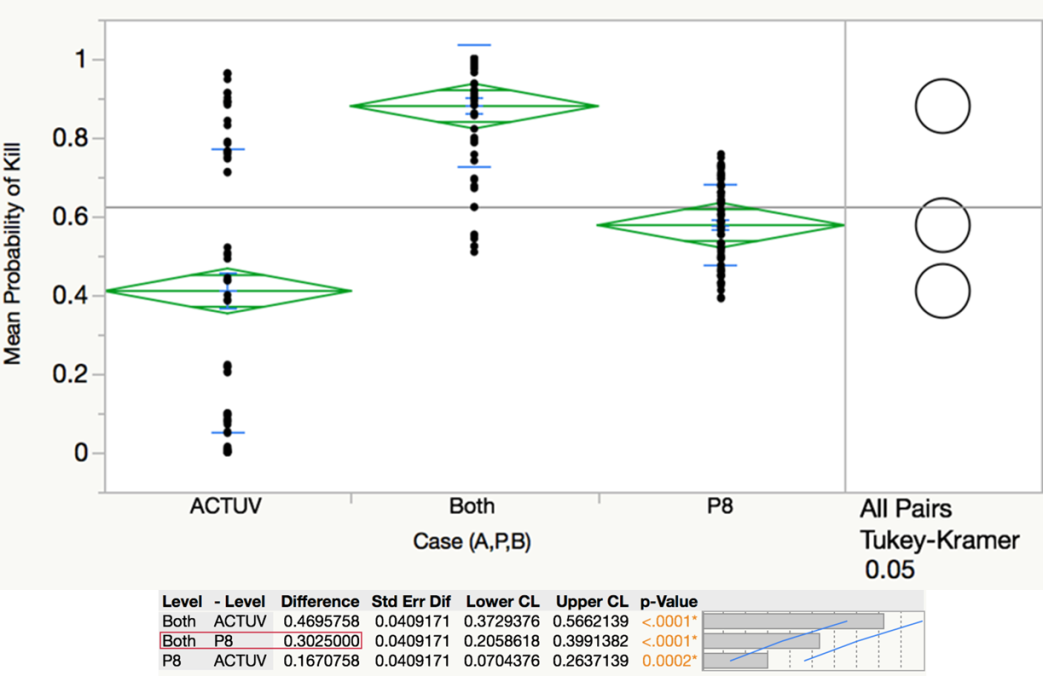

Figure 6: This plot shows the simulation results of an Area ASW engagement between a PLA Navy SSK submarine and the MDUSV alone (labeled ACTUV or Anti-Submarine Warfare Continuous Trail Unmanned Vessel, the original DAPRA program name); the MDUSV with a P-8 (labeled both), and the P-8 alone. The Tukey-Kramer test displays significant improvement with the MDUSV and P-8 work as an unmanned-manned pair.

Unique employment concepts are also developed, such as employing paired MDUSVs working as an active-passive team for both active radar and acoustic search. This information is passed to both sponsors and the NPS combat systems research faculty for engineering analysis.

LT John Tanalega’s Joint Campaign Analysis efforts included analyzing the MDUSV’s contribution to a scouting advantage for Blue forces in a surface-to-surface engagement (see figure 5). While a student in the NPS Wargaming Class, John’s team designed, developed, and executed a classified South China Sea game for United States Fleet Forces Command exploring distributed maritime operations and a force structure that included the MDUSV. Lessons from both classes were then applied to his further research in the MDUSV’s best tactical employment in a surface to surface engagement.

Furthering the study by use of simulation (Problem, Tactical Engagement, and Design of Experiments)

In transitioning MDUSV from technical concept to operational reality, several questions are prominent. First, MDUSV is just what its name implies—a vessel. The specific technologies which will make it effective in the maritime domain are all in various stages of development, and they are too numerous for MDUSV to carry all of them. Therefore, an exploration of which capabilities improve operational effectiveness the most is essential. Second, while superior technology is necessary, alone it is not sufficient. USVs must also be used with effective tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) to make them effective SUW platforms. USVs are entirely new to the U.S. Navy, and no historical data exists for their use in combat. Modeling, simulation, and data farming7 provide an opportunity to explore concepts and systems that, today, are only theories and prototypes.

Computer-based modeling and simulation are an effective means of exploring MDUSV capabilities and tactics. Live experiments at-sea are always important to gather real-world data and provide proofs of concepts. However, they require a mature design. They are prohibitively expensive, and the low number of trials that can be conducted reduces the confidence levels of their conclusions. Computer-based modeling and simulation allows us to run tens of thousands of experiments over a wide range of factors. It is, therefore, better suited for design exploration. Using high-performance computing and special techniques in design of experiments (DoE), such as nearly orthogonal and balanced (NOB) designs, simulation experiments that would have taken months or years with legacy factorial designs can be can be performed in a matter of days. This highly efficient technique provides greater insights that inform and direct live experimentation and requirements development.

To explore the effects of MDUSV on surface warfare, LT Tanalega used the Lightweight Interstitials Toolkit for Mission Engineering using Simulation (LITMUS), developed by the Naval Surface Warfare Center, Dahlgren Division (NSWC DD). LITMUS is an agent-based modeling and simulation tool suited specifically to naval combat. Ships, aircraft, and submarines are built by users and customized with weapons, sensors, and behaviors to mirror the capabilities and actions of real-world combat systems. Using an efficient design of experiments and LITMUS scenario, over 29,000 surface battles were simulated with varied active and passive sensor ranges, MDUSV formations and armament, and emissions control EMCON policies.

To compare battle results, LT Tanalega used the probability of a surface force being first to fire a salvo of missiles against an adversary as a measure of effectiveness. This choice is motivated by the maxim of naval combat in the missile era to “fire effectively first,” and indicates a clear advantage in offensive tactics.8

Simulation Results (Unclassified)

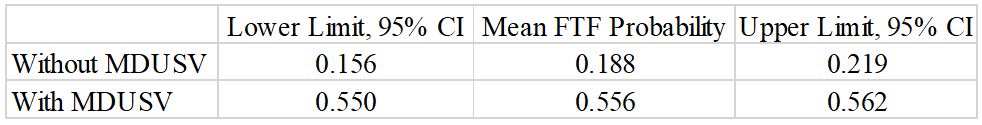

Analysis of the simulation output shows that a traditional Blue force combating a very capable Red force in its home waters has 19 percent probability of meeting first-to-fire criteria (See Table 1). Blue surface forces equipped with MDUSV are nearly three times as likely to be first-to-fire. Analysis also found the increase in performance is due primarily to the extended sensor range afforded by the TALONS platform on scouting MDUSV. Based on the presence of MDUSV alone, Blue improves its probability of being first-to-fire by a factor of nearly three (from 19 percent to 56 percent), as shown in Table 1. Though a SAG will likely have helicopters embarked, it is important to note that helicopters are more limited in endurance. Further, the use of a helicopter in Phase II of a conflict poses exceptional risk to human pilots, especially if the enemy is equipped with capable air defense systems. We therefore modeled “worst case” without an airborne helo during the engagements. Given the long endurance of MDUSV and its autonomous nature, MDUSV represents a worthwhile investment for the surface force. When numerically disadvantaged and fighting in dangerous waters, MDUSV levels the odds for Blue.

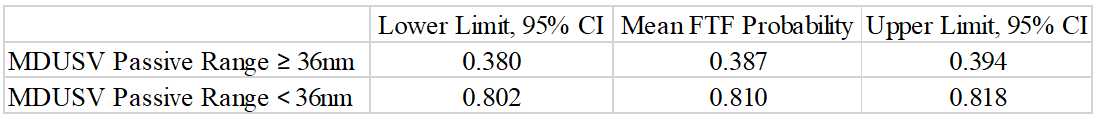

Advanced partition tree analysis of the data noted a breakpoint at an MDUSV passive sensor range of 36nm. With this range or greater, Blue was first-to-fire in 81% of the design replications (Table 2). Using the mathematical horizontal slant range formula to approximate visual horizon, this equates to a tether height of approximately 1020 feet. Given the current 150-pound weight limit for a TALONS payload, a passive electro-optical sensor may be more feasible than an active radar. Placing a high power radar, with power amplification, transmission, and signals processing in a TALONS mission package may not be feasible in the near term. Further study, from an electrical engineering and systems engineering perspective, is required.

While arming MDUSV provides a marginal increase in first-to-fire performance with EMCON policies 1 and 2, it has a small negative effect with EMCON policy 3. Ultimately, first-to-fire in each replication is driven by scouting—who saw whom and fired first. Since detecting the enemy is a necessary condition to shooting him, providing MDUSV with over the horizon sensor capabilities should be the first concern. This will allow the missile shooters of the surface and air forces to employ their weapons without emitting with their own sensors.

Furthering the Study by Use of Wargaming

The Fleet Design Wargame consisted of three separate gameplay sessions. During each session, the BLUE Team received a different order of battle. During gameplay, the study team observed the players’ decisions to organize and maneuver their forces, as well as the rationale behind those decisions. After two to three turns of gameplay, a member of the study team facilitated a seminar in which all players discussed the game results. Each team, BLUE and RED, had a leader playing as the “Task Force Commander,” and a supporting staff. The Blue Team consisted of three SWOs, a Navy pilot, an Air Force pilot, a Navy cryptologic warfare officer, two human resources officers, and a supply officer. The RED team consisted of three SWOs, one Marine NFO, one Navy cryptologic warfare officer, two Naval intelligence officers, and two supply officers. Search was adjudicated using probability tables and dice. Combat actions are being analyzed using combat models, such as a stochastic implementation of the salvo model.

Wargaming Results (unclassified)

The game demonstrated the combat potential that networked platforms, sensors, and weapons provide. Long endurance systems, such as the MQ-4C Triton and the Medium Displacement Unmanned Surface Vehicle (MDUSV) can be the eyes and ears of missile platforms like destroyers. The game also showed that with its range alone, an ASuW-capable Maritime Strike Tomahawk provides BLUE forces with greater flexibility when stationing units. On the other hand, unmanned systems also provide RED with a wider range of options to escalate and test U.S. resolve during phase 1. The study team also found that expeditionary warfare can have a double effect on the sea control fight. The presence of an LHA is a “double threat” to the enemy, acting as both an F-35B platform, and as a means of landing Marines.

Further Research Work on the MDUSV

Future research is required to optimize MDUSV design and to better characterize the human element of MDUSV employment and coordination. While TALONS provides a unique elevated sensor platform, a 150-pound maximum payload will be a considerable constraint. Passive sensors, such as EO/IR, may be mounted on the TALONS platform, but the weight required to house a high-performance radar will be a higher hurdle to overcome. Though this can be mitigated by changing the parasail design to increase lift, this will require more in-depth study of the engineering trade-offs. Also, the process will have to be automated. TALONS testing to-date has involved members of the test team deploying and recovering it.

Though this study was performed with software-driven automata, the tactical decisions leading-up to the placement of MDUSV will be made by humans. The long endurance of MDUSV makes it an ideal platform for deception. Tactical and operational level wargaming may yield insight into the affect that adding MDUSV will have on human decision-making.

As this study was the first SUW simulation of a man-machine teamed force, the scope of the agents explored was purposefully limited. To add to the realism of the experiment, and to explore future tactics, the addition of helicopters and other scout aircraft to the scenario may yield further insight into the design requirements and tactical employment of MDUSV.

MDUSVs in this study were homogenously equipped and shared the same EMCON policy. However, if each MDUSV is given only one capability, such as a particular sensor type or a weapon, their strengths may offset their weaknesses. Grouping several MDUSVs with different mission load-outs may be an alternative to sending a manned multi-mission ship like a DDG. It may also prove to be more resilient to battle damage, as the loss of a single MDUSV would mean the loss of an individual mission, while the mission-kill of a DDG would result in a loss of all combat capability. Further simulation and analysis with LITMUS may yield insights into this trade-off.

Other Examples

Although we have highlighted LT Tanalega’s recent research to demonstrate how the NPS Warfare Analysis group integrates officer’s tactical experience, classroom work, and more detailed research to provide insights in new technologies, tactics, and operational concepts, many other examples can be mentioned. These include tactics to defeat swarms of unmanned combat aerial vehicles, best use of lasers aboard ships, developing tactics to counter maritime special operations insertion, employing expeditionary basing in contested environments, exploration in distributed logistics, best convoy screening tactics against missile-capable submarines, and use of sea bed sensors and systems. Analytical red teaming is also used for sponsors wishing to better understand the resilience and vulnerability of their new systems—employed in the same classes mentioned in this paper. These results are shared with DoD and Navy sponsors interested in getting robust and quantitative assessments of the strengths and weaknesses of their systems.

Although the NPS Warfare Analysis group is pleased to make real-world contributions as part of our students’ education experience, our greatest satisfaction comes from observing the junior officer’s military professional growth that accompanies the application of their newly learned analytical skills. To model and analyze an engagement, a thorough understanding of the tactical factors and performance parameters is necessary. By the end of our students’ experience, they have gained expertise in that mission and in operations analysis—a perfect blend to contribute to our nation’s future force architecture and design.

CAPT Jeff Kline, USN (ret.) is a Professor of Practice in Military Operations Research at the Naval Postgraduate School. He holds the OPNAV N9I Chair of Systems Engineering Analysis and teaches Joint Campaign Analysis, Systems Analysis, and Risk Assessment. jekline@nps.edu

Dr. Jeff Appleget is a retired Army Colonel who served as an Artilleryman and Operations Research analyst in his 30-year Army career. He teaches the Wargaming Analysis, Combat Modeling, and Advanced Wargaming Applications courses. Jeff directs the activities of the NPS Wargaming Activity Hub. He is the Joint Warfare Analysis Center (JWAC) Chair of Applied Operations Research at NPS. jaappleg@nps.edu

Dr. Tom Lucas is a Professor in the Operations Research Department at the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS), joining the Department in 1998. Previously, he worked as a statistician and project leader for six years at RAND and as a systems engineer for 11 years at Hughes Aircraft Company. Dr. Lucas is the Co-Director of the NPS Simulation, Experiments, and Efficient Design (SEED) Center and has advised over 100 graduate theses using simulation and efficient experimental design to explore a variety of tactical and technical topcs. twlucas@nps.edu

LT John F. Tanalega is a Navy Surface Warfare Officer from North Las Vegas, Nevada and is a 2011 graduate of the United States Naval Academy His first operational tour was as Auxiliaries and Electrical Officer, and later as First Lieutenant, in USS DEWEY (DDG 105). He next served as Fire Control Officer in USS JOHN PAUL JONES (DDG 53). As an operations analysis student at the Naval Postgraduate School, his research focused on combat modeling, campaign analysis, and analytic wargaming. After graduating from NPS, he reported to the Surface Warfare Officer School (SWOS) in Newport, Rhode Island, in preparation for his next at-sea assignment.

References

1. Sanchez, S.M., T.W. Lucas, P.J. Sanchez, C.J. Nannini, and H. Wong, “Designs for Large-Scale Simulation Experiments with Applications to Defense and Homeland Security,” Design and Analysis of Experiments, volume III, by Hinckleman (ed.), Wiley, 2012, pp. 413-441

2. Kline, J., Hughes, W., and Otte, D., 2010, “Campaign Analysis: An Introductory Review,” Wiley Encyclopedia of Operations Research and Management Science, ed Cochran, J. John Wiley & Sons, Inc

3. Appleget, J., Cameron, F., “Analytical Wargaming on the Rise,” Phalanx, Military Operations Research Society, March 2015, pp 28-32

4. Appleget, J., Cameron, F., Burks, R., and Kline, J., “Wargaming at the Naval Postgraduate School,” CSIAC Journal, Vol 4, No 3, November 2016 pp 18- 23

5. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has demonstrated a prototype “Sea Hunter”. Information may be found at https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2018-01-30a

6. For more information on the TALON visit https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BWEoV88PtTY

7. See Sanchez, ibid.

8. Hughes, W.P., Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat, 2nd ed, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 2000.

9. Wagner D.H., Mylander, W.C., Sanders, T.J., Naval Operations Analysis, 3rd ed, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 1999, pp 109-110.

Featured Image: The Medium Displacement Unmanned Surface Vehicle (MDUSV) (DARPA photo)