By Dmitry Filipoff

For the past week, CIMSEC featured a series of submissions sent in response to our Call for Articles for short notes on what the new U.S. administration can consider to strengthen American naval power, reinforce alliances, and compete effectively against great powers. Authors examined a multitude of issues and offered recommendations for reform. From shipbuilding shortfalls to competing with China, to reinforcing alliances and strengthening logistics, the new administration faces many challenges and opportunities in the maritime domain.

Below are the authors that featured during this series. We thank them for their contributions.

“Prepare the Navy and Marine Corps for Protracted War against China,” by Walker Mills

“There is no reason the U.S. military should expect a conflict with the PRC to be short, or to be won quickly. Rather, history tells us the opposite. Why would we expect the world’s most populous country and the second-largest economy to back down after only the opening salvo of a war it started, even if the opening round went poorly?”

“Restore Wargaming Focus to the Naval War College,” by Captain Robert C. Rubel, USN (ret.)

“The Naval War College was the critical engine that drove the warfighting education of the officer corps that designed, perfected, and fought the fleet that produced victory at sea in World War II. But today, the college has become moribund in terms of its relevance to the emerging warfare environment.”

“U.S. Ground Forces Can Check Chinese Naval Advantage Now,” by Brian Kerg

“While it may take the U.S. years to build a single ship, it can raise, man, and equip ground forces optimized for operations on key maritime terrain at the speed of relevance, raising minimally required forces in under a year. Such forces, once raised, can achieve asymmetric and decisive strategic deterrent effects through permanent deployment to decisive points within the territory of U.S. allies such as Japan and the Philippines, and partners such as Taiwan.”

“The Best of Both Worlds: Educating Future Navy Officers,” by Claude Berube

“The Navy should have one commissioning source – the U.S. Naval Academy. But it should be adapted to benefit from other educational programs and experiences domestically.”

“Fill the Vacuum: Establish a Sustained Naval Presence in the Yellow Sea,” by William Martin

“In recent years, China has increased its aggressive activity in this vital maritime lane, to the detriment of U.S. interests, the security of allies, and the maintenance of a free and open Indo-Pacific. The United States and its allies must increase force presence along this key maritime terrain to disrupt PLA confidence in freely maneuvering through these waters as they conduct operations counter to U.S. interests.”

“Found in Translation: Bolster U.S. Coalition Warfighting by Fixing the Linguist Shortfall,” by Benjamin Van Horrick

“Linguists will serve as an invaluable link in the killchain during wartime. All available assets from across the coalition must be brought to bear to make sense of the environment, prosecute targets, and support maneuver in all forms. Linguists will minimize friction and the fog of war as coalition members shorten the time between sensing and striking a target – no matter what country the capabilities originate from.”

“ESBs for Intermediate Naval Lift in Support of Expeditionary Operations,” by Major Christopher “Pink Sheets” Lowe, USMC

“To increase the capability of the naval expeditionary force to meet the demands across the global maritime commons and in non-permissive maritime environments, the Navy should acquire at least 30 Lewis B Puller (ESB-3)-class Expeditionary Mobile Base ships.”

“A High-Low Naval Portfolio: Maximize Strategic Returns with Balanced Force Design,” by Andrew Tenbusch and Trevor Phillips-Levine

“To remain both cost-effective and globally engaged, the U.S. Navy needs a balanced mix of high-end capital ships and smaller, more economical vessels, even if the latter are inherently less armed and defended. This tradeoff is not only acceptable but strategically beneficial, given the Navy’s role in day-to-day operations.”

“An Investment in the U.S. Navy is an Investment in Prosperity,” by Sam J. Tandgredi

“The U.S. Navy has a purpose that goes beyond warfighting. It is a critical geo-economic instrument that through global naval dominance helps sustain the U.S. dollar as the world reserve currency. An investment in naval dominance is an investment in continued prosperity. Without it our future will be poorer.”

“Refocus on Warfighting To Boost Recruiting and Retention,” by Karl Flynn

“Make America’s youth want to serve by clearly stating our national security imperatives, minimize distractions from core warfighting functions, and eliminate all lowered standards.”

“Reconsider Red Sea Risk: Revealing U.S. Navy Air and Missile Defense Capability to China,” by Clay Robinson

“China’s relatively unfettered access to significant quantities of data on U.S. combat engagements, and their ability to glean the capabilities and limitations of critical U.S. Navy air and missile defense capabilities, may represent a far greater boon for them in the long run.”

“Work with Allies to Strengthen Deterrence against China,” by Michael Tkacik

“It is increasingly clear that China has the advantage in a long war, making the current state of deterrence untenable. Therefore, the U.S. must seek partners to increase the costs of Chinese revisionism and augment U.S. capabilities.”

“Build Containerized Missile Ships for Rapid and Affordable Fleet Growth,” by Captain R. Robinson Harris, USN (ret.) and Colonel T.X. Hammes, USMC (ret.)

“There is a solution that is faster and more affordable – purchase used merchant container ships and outfit them with containerized missiles, drones, and other modular capabilities.”

“Balance AUKUS and Amphibious Fleet Readiness,” by Chris Huff

“While a strategic success with long-term benefits, AUKUS has introduced challenges due to increased costs, resource competition, and extended production timelines for Virginia– and Columbia-class submarines. These issues have adversely affected the Navy’s amphibious fleet, undermining the Marine Corps’ ability to maintain readiness and execute its vital global responsibilities.”

“It is Time for a New Maritime Strategy,” by Peter Dombrowski

“An ambitious new maritime strategy will help the Navy raise more resources, generate positive attention from the Office of the Secretary of Defense, and win appropriate congressional guidance to set the Navy on the right course for the coming decade. If the Navy is to meet the pacing threat posed by the PLA Navy, it must rally public support, galvanize Congress, and convince the world that the United States fully remains the world’s premier naval power.”

“Invest in Sustainment Capabilities to Increase Combat Credibility,” by Joseph Mroszczyk

“The new administration must urgently focus its efforts on strengthening the U.S. military’s combat credibility in the Western Pacific through investments in capabilities that enable at-sea and distributed logistics. To deter the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from aggression against Taiwan, the U.S. military must demonstrate it can effectively sustain combat at great distances and across a distributed force.”

“Rebuild Commercial Maritime Might to Restore U.S. Sea Power,” by Commander Ander S. Heiles, USN

“The administration faces an urgent choice – continue America’s narrow focus on naval power or comprehensively rebuild the commercial capability Mahan identified as essential to national power. By restoring the balance between combat and commercial maritime capabilities, the U.S. can secure its position in the era of great power competition.”

“It is Time for a Real Maritime Strategy: Focus on Shipbuilding, Seafaring, and Sway,” by Christopher Costello

“The United States needs a true, comprehensive maritime strategy. It takes the form of an interconnected effort that recognizes that seapower does not flow from naval power alone and the conditions under which the U.S. developed into a great maritime power have shifted. Readjustment is necessary.”

“It is Time to Build Small Warships,” by Shelley Gallup and Ben DiDonato

“Scholars and engineers at the Naval Postgraduate School have developed a bi-modal fleet concept featuring a mix of small sea denial and large sea control vessels to correct this weakness. The key to implementing this strategy is the LMACC, or Lightly Manned Automated Combat Capability.”

“The Specter of Tariffs and the Revival of the U.S. Merchant Marine,” by Ben Massengale

“Imposition of those tariffs could provide a window of opportunity to revive the U.S. Merchant Marine by making foreign vessels less competitive in conducting trade in the U.S. This could be done by granting cargo imported by U.S.-flagged vessels a reduced tariff to not only compensate for the additional cost it takes to operate an American ship, but also making its operations significantly more profitable than its foreign competitors.”

“Develop Strategies to Counter China’s Gray Zone Tactics,” by Roshan Kulatunga

“China’s approach involves a systematic infiltration of various sectors, including technology, academia, media, and even political domains, to gather intelligence and insights into the strategies of possible adversaries. This multifaceted approach allows China to build a nuanced understanding of U.S. capabilities and intentions while subtly undermining them.”

“Strengthen America’s Maritime Borders,” by David Ware

“What is concerning today is that the DHS intelligence and enforcement posture for national security purposes, for both large and small vessels, appears to have taken a backseat to focus strictly on immigration concerns. This creates a maritime security opening for adversaries to exploit.”

“Reassess the Navy’s Global Force Posture,” by Francis Crozier

“The Navy must choose its battles more carefully and come to grips with the limited resources it currently has. Repeatedly extending deployments for surface combatants and carriers critical to a war with China will result in long-term consequences for readiness, as exemplified by incidents like the delayed Boxer ARG deployment.”

“Legislate New Fleet Acts for a Generational Investment in Naval Power,” by Jason Lancaster

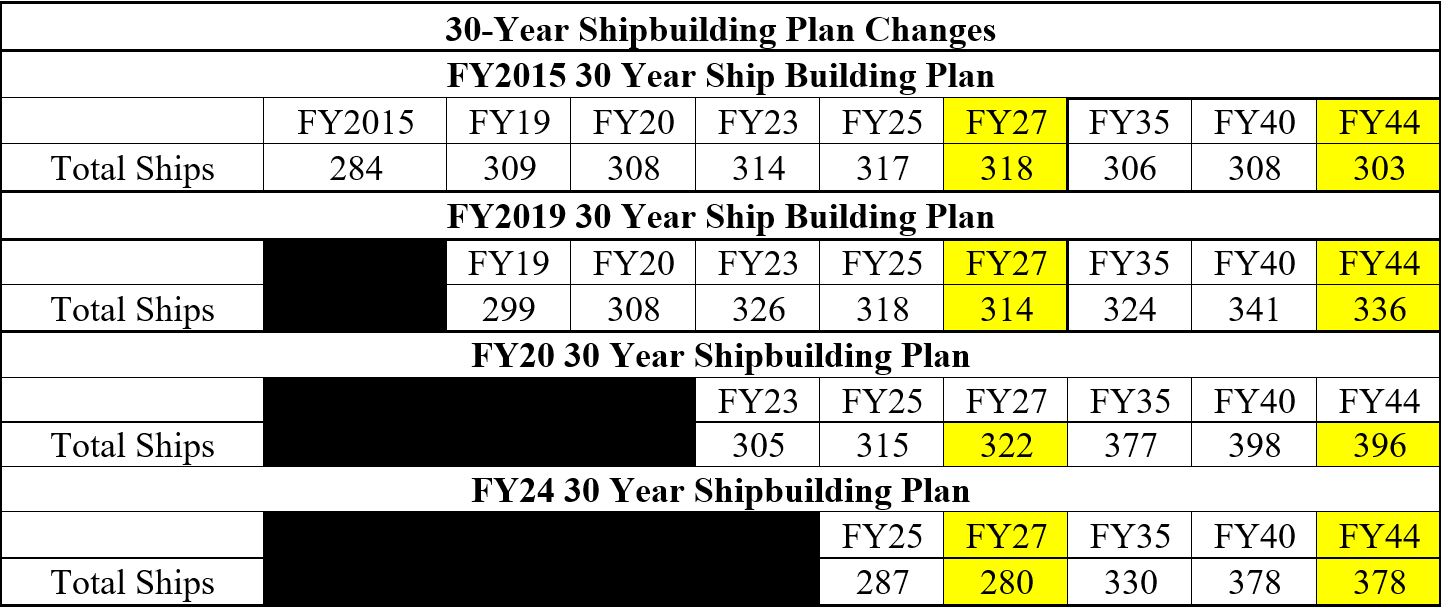

“A fleet act could provide a more viable mechanism for adjusting the Navy’s force structure and making a generational investment in naval power compared to the 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan, which has lost much of its usefulness.”

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. Contact him at [email protected].

Featured Image: Ships and submarines participating in the Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise sail in formation in the waters around the Hawaiian Islands July 27, 2012. (U.S. Navy Photo)