Where is the U.S. Navy Going To Put Them All?

Part 1: More Drones Please. Lot’s and Lot’s of Them!

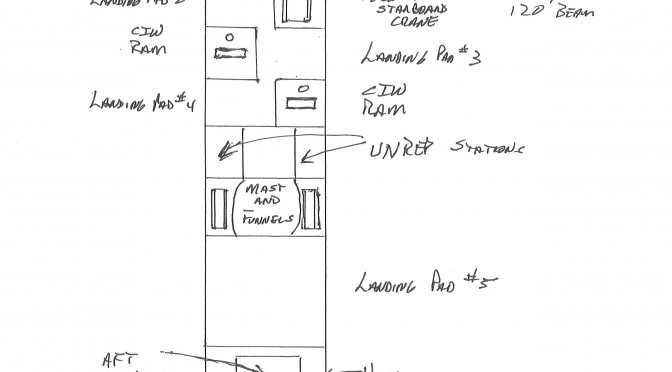

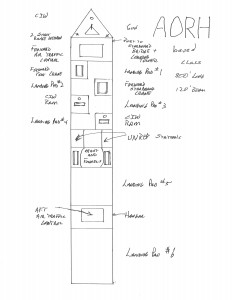

Sketch by Jan Musil. Hand drawn on quarter-inch graph paper. Each square equals twenty by twenty feet.

Recent technological developments have provided the U.S. Navy with major breakthroughs in unmanned carrier landings with the X-47B. A public debate has emerged over which types of drones to acquire and how to employ them. This article suggests a solution to the issue of how to best make use of the new capabilities that unmanned aircraft and closely related developments in UUVs bring to the fleet.

The suggested solution argues for taking a broader look at what all of the new aerial and underwater unmanned vehicles can contribute, particularly enmasse. And how this grouping of new equipment can augment carrier strike groups. In addition, there are significant opportunities to revive ASW hunter killer task forces, expand operational capabilities in the Arctic, supplement our South China Sea and North East Asia presence without using major fleet elements and provide the fleet with a flexible set of assets for daily contingencies.

These sorts of missions provide opportunities for five principal types of drones. Strike, ISR and refueling drones as winged aircraft to fly off fleet platforms, UUVs and the Fire Scout helicopter. So we have five candidates to be built, in quantity, for the fleet. Let’s examine each of the suggestions for what they should be built to accomplish, what sort of weapons or sensors they need to be equipped with and what doctrinal developments for their use with the fleet need to happen.

Strike drone

The current requirements are calling for long range, large payload, and the ability to aerially refuel and are to be combined with stealth construction techniques for the airframe, even if not stealth coated. These size and weight parameters mean this drone will require CATOBAR launching off an aircraft carrier’s flight deck. Which also means it will be supplementing, and to some extent replacing, the F-35C in the air wings for decades to come. The merits of how many strike drones versus F-35Cs, and the level of stealth desired for both, will be an ongoing debate for the foreseeable future.

Given that a strike drone built with these capabilities will be tasked with similar mission requirements to the F-35C, we will assume for now that the weapons and ISR equipment installed will be equivalent, if not exactly the same as the F-35C. This implies that whatever work the U.S. Navy has already done in developing doctrine for use of the long range strike capacity the F-35Cs brings to the fleet should only need to be supplemented with the addition of a strike drone.

It is worth remembering that while these drones are unmanned, since they are CATOBAR they will still require sailors on deck to move, reload and maintain them. Sailors who also need a place to eat, sleep, etc.

And the carriers are already really busy places. However welcome the strike drone winds up being, there is not going to be enough room on the carriers to be add even more equipment. Therefore each drone will be replacing something already there, both physically within the hangar bay and financially within the Navy’s budget.

ISR drone

Most of the current public discussion surrounding an ISR equipped drone is rather hazy about what sort of sensors, range and weapons, if any, are wanted. However, the philosophical debate over mission profile, including a much smaller size, localized range requirement and the presumed emphasis on ISR tasks is revealing. The key points to concentrate on for such a drone are the suggested set of missions to be conducted by an arc of ISR drones around a selected location, sensor and networking capabilities, range and durability requirements and a limited weapons payload.

The traditional use of aerial search capabilities onboard a carrier task force was over the horizon, well over the horizon thank you very much, locating of the opponents surface assets. Over the years the extended ranges of aircraft and the development of airborne ASW assets changed the nature of the search and locate mission and the assets being used to conduct it. Adding space based surveillance changed things once more. The coming improvements in networking and data processing capabilities inside a task force, a steadily rising need for over the horizon targeting information coupled with the need to function within an increasingly hostile A2AD environment has once more altered the requirements of the search and locate mission. Search and locate essentially has become search, locate, network and target.

Being able to fund as well as field large numbers of anything almost always means keeping it smaller, and deleting anything not strictly needed beyond occasional use is an excellent way to accomplish this. For the ISR drone, not arming it with anything beyond strictly self-defense weapons is an excellent way to keep size and costs down. Since the primary missions of the ISR drone will be the new search, locate, network and target paradigm, concentrating funding on those capabilities is an excellent way to limit both development and operating costs.

Particularly since putting a large number of the drones, each capable of at least 24-30 hours on station, supplemented by refueling, in an arc around a task force in the direction(s) of highest concern means that the SuperHornets of the fleet can largely be freed from the loiter and defend mission and return to being hunters.

Since I am assuming the railgun will also be joining the fleet in large numbers some discussion about the range of the search, locate, network and target arc suggested above as it relates to the railgun is in order. The publicly disclosed range of the railgun is 65 miles, so an arc of ISR drones needs to be farther out from the task force than that, quite some way beyond that to provide time to effectively network location and target data developed back to the shooters. In the anticipated A2AD environment the primary threat is very likely to be a missile, mostly subsonic but the potential for at least some of them being hypersonic exists. Therefore, the incoming missiles or aircraft will need to be located, networked information sent to the surface assets armed with railguns and the targeting information processed quickly enough that the bars of steel launched as a result will be waiting for the incoming missile at 65 miles. Precisely how far out beyond the railguns effective range the arc of ISR drones will need to be will almost certainly vary by circumstance and the nature of the opponent’s weaponry. Nevertheless, whether subsonic or hypersonic, missiles move rapidly and this means an effective arc of ISR drones will have to be a long distance out from the task force. The farther out the arc is, a higher number of drones will be needed to provide adequate coverage.

This implies a need for a minimum of 6-8 ISR drones on station, 24/7, in all kinds of weather. Since there are inevitable maintenance problems cutting into availability time, this implies a task force will need take twice that number to sea with it. Particularly if a second arc of two or three ISR drones is maintained just over the horizon, or simply overhead. This inner group can also provide local networking abilities for the ASW assets of the task force. Having at least one ISR drone close in to provide a rapid relay of information around the task force by its sub hunters should also be planned for as a doctrinal necessity.

This arc of ISR drones is a wonderful new capability to have, but…., but fifteen drones are not going to fit on a CVN. Not when an essentially equivalent number of something else needs to be removed to make room for the newcomers. Our carriers are packed as it is with needed airframes and trading out fifteen of them from the existing air wing is not going to happen.

Nor is there room elsewhere in the fleet. The CCGs and DDGs have limited space on their helo decks, but even if the new ISR drone were equipped with the modified VTOL engine from the Osprey program, there still wouldn’t be space for more than a few of them. Once more, it is a case of needing to take something out of the fleet to put the new capability in.

This means we have to build a new class, or classes, of ships to operate and house the quantities of drones desired, including operating space, hanger and maintenance space and sailor’s living spaces.

Refueling drone

A drone primarily dedicated to the refueling mission takes on another of the un-glamorous, but unending tasks involved in operating a task force. Instead of the proposed return of the S-3 Vikings as tankers, a somewhat larger drone can be designed from scratch to be a flying gas station with long range and loitering times, presumably with vastly more fuel aboard and built to only occasionally load weapons or sensors under the wings. It could have ISR capabilities or ASW weapons slung under the wings as distinctly secondary design characteristics. In understanding when to use manned versus unmanned systems obviously any extra weight and space gained by losing a cockpit allows for more fuel carried, longer loitering times and extra range. These advantages need to be balanced against the occasional need for a pilot’s skills on scene.

UUVs

As for the UUVs in development, much has been made of their ability to dive deeply and search for things as well as their ability to autonomously operate far out in front of a task force, including the possibility of submarine launched missions. While interesting a more incremental use of the roughly six feet long torpedo shaped UUV currently in use for deep diving missions might be more appropriate.

While we wait on further research developments to establish ways to effectively utilize a long range, long duration UUV reconnaissance drone, a more mundane use of what we have right now can readily be used for ASW purposes. We could equip a six-foot UUV with the sensors already in use for ASW purposes and cradle it in open sided buoy in order to hoist the UUV in and out of the water. This buoy could be used over the side, or far more usefully, launched and recovered by helicopter. Wave and say hello Fire Scouts.

Fire Scouts

Any helicopter asset that the U.S. Navy has can be used of course, but without a pilot aboard the Fire Scouts are much better suited for the long hours required to successfully prosecute ASW. Taking off with the UUV cradled inside it’s buoy, the Fire Scout can deploy the buoy, allow the tethered UUV to swim to the thermocline or other desired depth, hover while allowing the UUV to transmit or simply silently listen, wait for the resulting data that is collected to be reported via the tether and broadcast by an antenna on the buoy and then once the UUV has swum back into it’s cradle within the buoy, drop back down and relift the buoy and move it to the next needed position. This redeployment can be hundreds or thousands of yards away at the mission commander’s discretion. This cycle can be repeated as many times as wanted or fuel for the Fire Scout allows. A difficulty that can be resolved aboard the nearest surface ship with a helo deck, leaving the buoy drifting in place, UUV on station and transmitting as refueling takes place. Shift changes by pilots should not materially interrupt this cycle. The most likely limitation that will force the Fire Scout to lift buoy and UUV out of the water for return aboard will be the exhaustion of the power source aboard the buoy being used to operate the reel for the tether and broadcast the data collected to an overhead airframe. Which just happens to be another use for the ISR drone or a ScanEagle.

In the next article we will examine how the Navy can make profitable use of UUVs and buoys, deployed and maneuvered across the ocean by the Fire Scout helicopter, in quantity, in pursuit of the ASW mission. Read Part Two here.

Jan Musil is a Vietnam era Navy veteran, disenchanted ex-corporate middle manager and long time entrepreneur currently working as an author of science fiction novels. More relevantly to CIMSEC he is also a long-standing student of navies in general, post-1930 ship construction thinking, and design hopes versus actual results and fleet composition debates of the twentieth century.