Surviving the Fabled Thousand Missile Strike

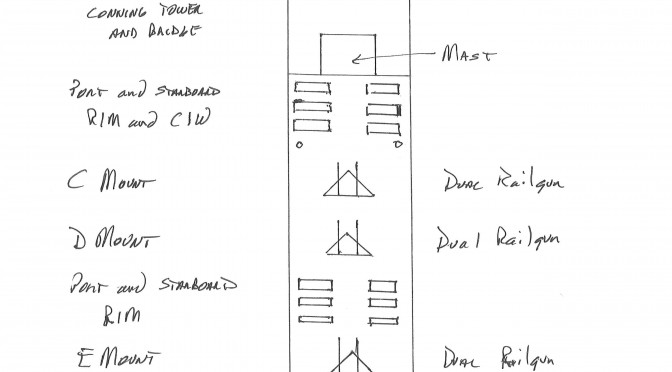

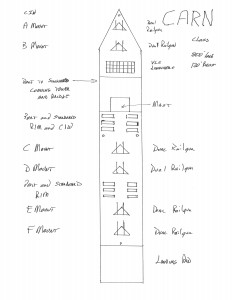

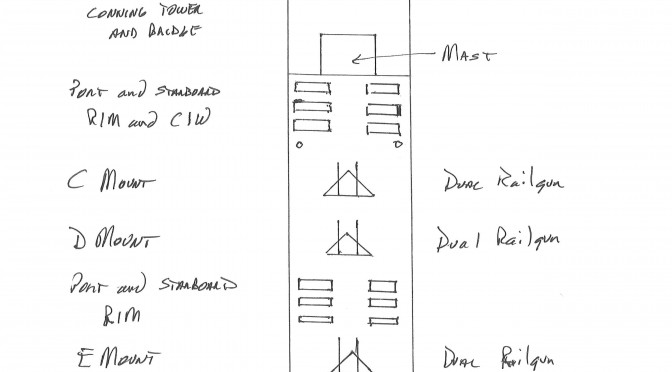

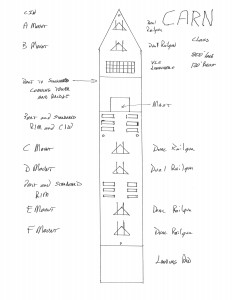

Sketch by Jan Musil. Hand drawn on quarter-inch graph paper. Each square equals twenty by twenty feet.

This article, the fifth of the series, examines how fitting lots of drones, of all types, and large numbers of railguns, aboard a CVLN and either one or two CARNs, can allow the U.S. Navy to confidently ride out the fabled thousand missile strike from the mainland of Eurasia. To do so let’s walk through a possible exercise involving Red, a Eurasian mainland power and Blue, essentially a typical Western Pacific carrier strike group. Read Part One, Part Two, Part Three, Part Four.

Red’s motivation might be ensuring that Blue cannot interfere with, or arrange for reinforcements to reverse, an offshore invasion. An alternative, somewhat more likely though, is that Red is intent on challenging one of Blue’s friends or allies and finds that it cannot achieve its objectives without removing Blue’s powerful naval forces from the area. When threats and warnings do not result in a satisfactory result, Red’s leader authorizes a massive missile strike on Blue’s carrier strike group at sea. This missile strike will be an attempted TOT (time-on-target) strike where all the missiles launched, regardless of distance to the carrier strike group or their speed, i.e. a combination of subsonic and hypersonic missiles, will arrive within a five minute window at the target location. The strike will primarily consist of land-based missiles, but some of Red’s numerous submarines will attempt to participate as well, for the purposes of this exercise it is assumed 29 missiles launched from three different submarines will arrive on target within the five minute TOT time period. Red’s commander has elected to hold his meaningful, though not massive, long-range aircraft striking power in reserve, hovering in a threatening position but not immediately participating. Thus a total of 1,029 missiles are launched.

This exercise assumes that Red can coordinate the command and control challenges involved in such a large undertaking. It also assumes that Red possesses adequate space based surveillance capabilities that real time targeting information down to the nearest kilometer, or better, is available on a timely basis to the relevant land, air and submarine commanders.

It should be emphasized here the importance of the compressed TOT portion of Red’s attack plan. Any incoming missiles, whether land or sub launched will be far easier for Blue to defend against if straggling in before or after the massed attack. This advantage of Blue’s is magnified by the presence of the railguns with their enormous magazine size and the ability to fire every five seconds.

It is assumed that Blue’s carrier strike group consists of:

1 CVN

1 CVLN

1 CG (Ticonderoga class)

1 CARN

4 DDG (Arleigh Burke)

4 FF (the new ASW frigate under development)

2 squadrons of F-18s

6 EA-18G Growlers

1 squadron of F35s

1 squadron of strike drones

15+ ISR drones

4 E-2D Hawkeyes

2 S-3 Vikings

6 refueling drones

15+ Fire Scouts

10+ Seahawks

75+ buoys with UUVs or a dipping sonar installed and a radar/infrared lure

Blue’s carrier strike group commander has taken full advantage of the ASW capabilities provided by all the Fire Scouts and buoys, spreading the strike group out over a thirty mile radius in a preplanned dispersal strategy. The commander has also been successful at maneuvering the strike group into a position where there are no Red submarines within at least 30 miles, and it is believed (or hoped) by Blue’s commander that the strike group is at least 50 miles from the nearest Red submarine.

Blue also possesses space based surveillance capabilities and is able to provide Blue’s carrier strike group a twenty minute warning of the incoming attack. Blue’s commander selects one of his preplanned spatial deployment plans, concentrating the majority of his surface assets in a compact zone with the CARN taking position and turning its broadside closest to the incoming missile strike, three of the four DDGs some distance behind it, then the CG and two of the frigates, then the CVLN and finally the CVN. One frigate is so far off on the periphery on ASW duty that it will fire chaff rounds repeatedly during the attack and hope the handful of aircraft overhead and many radar lures dropped in its vicinity will allow it to emerge unscathed. On the opposite side of the strike group one DDG and the fourth frigate will do the same, though with the added protection of the DDGs AAW missiles.

This dispersion plan means a large portion of the area where the strike group is located is simply empty ocean. The intent is to use the strike groups EEW and radar lures to effect and make thorough use of the fact that even a subsonic missile cannot maneuver quickly enough to search out targets if presented with enough empty ocean upon their initial arrival at the selected target location.

Blue’s commander has also chosen a specific plan for utilizing his air assets in a layered defense, intent on maximizing the effectiveness of the various weapon systems embarked. Let us follow the resolution of the attack, starting with the outermost layer, and work our way inwards as the strike progresses.

Cap Layer

2 E-2D Hawkeyes and 12 F-18 Super Hornets

Blue’s strike group commander has assigned these air assets to anti-aircraft duty, approximately 250 miles from the strike group’s location. Since Red’s long-range bombers are known to be airborne, but apparently are not immediately participating, the decision is taken for these Super Hornets to hold their fire, confident that the rest of the strike group can deal with the incoming missiles, and continue to guard against any enemy aircraft that might intrude later.

Shot Down/Eliminated/Missed/Decoyed This Layer: Zero

SD/E/M/D Cumulative: Zero Of 1,029 incoming missiles

ISR Drones Layer

8 ISR Drones

These eight drones are individually scattered in an arc 150 miles out from the strike group’s location. They are there to provide accurate targeting information, primarily for the SM-2 and railgun equipped surface ships of the strike group. In particular the presence of this arc ensures timely targeting information so the railguns can effectively engage at their maximum range of 65 miles.

SD/E/M/D This Layer: Zero

SD/E/M/D Cumulative: Zero Of 1,029 incoming missiles

Railgun Layer

13 railguns (12 on the CARN and 1 on the CVLN)

With the targeting information provided initially by the ISR drones and later by the various aircraft and AAW radars of the strike group the railguns will steadily engage at their maximum rate of every five seconds. Since it is unlikely that any particular missile, even subsonic ones, will not close the remaining 65 miles to the strike group before a second shot can be taken this exercise assumes each railgun will only fire once at any given missile.

Each railgun can fire every seconds, 60 seconds/5 = 12 shots a minute. Therefore over a five minute time period each railgun will get off 5 x 12 = 60 carefully aimed shots. 13 railguns x 60 equals 780 opportunities to hit an incoming missile.

This exercise will assume a 50% success rate for the railguns. Therefore 390 incoming missiles are eliminated.

SD/E/M/D This Layer: 390

SD/E/M/D Cumulative: 390 Of 1,029 incoming missiles

SM Family Missile Layer

420 surface ship launched SM-2 missiles and 2 E-2D Hawkeyes operating approximately fifty miles out from the strike group’s location.

The CG (100) and four DDGs (80 each) in the strike group are assumed to have 420 SM-2 missiles available to fire in their collective VLS cells.

This exercise will assume a 70% success rate for the missiles. Higher success rates can easily be argued for, though there will be some unavoidable overlap with the railguns resulting in double targeting by some missiles. 420 x .70 = 294. Therefore 294 incoming missiles are eliminated.

SD/E/M/D This Layer: 294

SD/E/M/D Cumulative: 684 Of 1,029 incoming missiles

Air Wing Layer

12 F-35s, 12 Strike Drones, 12 F-18 Super Hornets, 6 EA18-G Growlers, and 2 S-3 Vikings carrying 4 air-to-air missiles each = 176 AAW missiles

Blue’s air commander has elected to concentrate the bulk of his air assets close to the strike group. This allows the air commander to attempt to concentrate this groups AAW missiles in defense of the three zones occupied by the surface ships below. This allows more of the incoming missiles that have survived to this point but appear to be targeted on empty ocean to be ignored.

This exercise will assume a 70% success rate for the AAW missiles. Again, higher success rates can easily be argued for, though given the tight time constraints on pilots decision making some double targeting will be unavoidable. 176 x .70 = 123.2 rounded down to 123. Therefore 123 incoming missiles are eliminated.

SD/E/M/D This Layer: 123

SD/E/M/D Cumulative: 807 Of 1,029 incoming missiles

Eliminated Due to Malfunction Layer

If everything always worked perfectly the world would be a much happier place. But things inevitably go awry and the incoming missiles are not immune to this problem. This exercise assumes a standard 5% malfunction rate. 1,029 x .05 = 51.45, rounded down to 51.

SD/E/M/D This Layer: 51

SD/E/M/D Cumulative: 858 Of 1,029 incoming missiles

Missed Due to Dispersal Layer

The high rate of speed of the incoming missiles will sharply limit their ability to effectively search for a target if they happen to encounter one of the areas of empty ocean Blue’s commander has contrived. This exercise assumes, rather arbitrarily, a 5% missed rate, but empty ocean will certainly greet some of Red’s missiles. 1,029 x .05 = 51.45, rounded down to 51.

SD/E/M/D This Layer: 51

SD/E/M/D Cumulative: 909 Of 1,029 incoming missiles

Decoyed Layer

The strike groups EEW capabilities, including the Growlers, all the strike group helicopters, Fire Scouts and over 75 buoys with various types of lures aboard can be utilized to great effect. This exercise assumes, rather arbitrarily, a 5% decoyed rate. It is tempting to select a higher rate, but to be conservative the 5% rate is used. 1,029 x .05 = 51.45, rounded down to 51.

SD/E/M/D This Layer: 51

SD/E/M/D Cumulative: 960 Of 1,029 incoming missiles

Internal Rolling-In-Frame Layer

The CARN has six rolling-in-frame close defense missile launchers installed on each side of the ship. As Red’s surviving missiles reach the LOS horizon, these missiles engage those missiles targeted on the primary layered group of surface ships, which includes the crucial CVN.

This exercise will assume a 70% success rate for these missiles. 48 x .7 = 33.6, rounded down to 33. Therefore 33 incoming missiles are eliminated.

SD/E/M/D This Layer: 33

SD/E/M/D Cumulative: 993 Of 1,029 incoming missiles

Last Ditch Layer

At this point the last 36 missiles of the original 1,029 are assumed to acquire surface targets and close on them. At this point the targeted ships individual CIW and close range missile defense provide a last ditch defense layer.

To be consistent, this exercise will assume a 70% success rate for the CIW and close range defense missiles. 29 x .7 = 20.3, rounded down to 20. Therefore 20 incoming missiles are eliminated.

SD/E/M/D This Layer: 20

SD/E/M/D Cumulative: 1,013 Of 1,029 incoming missiles

The hits the remaining 26 missiles inflict will do varying amounts of damage, with the highest variability being the size of the target. One hit can easily destroy one of the ASW frigates. Depending on where the hit occurs, damage to a DDG or the CG will merely damage some portion of its functionality but the combination of the damage and the resulting fires could easily incapacitate the ships fighting ability for quite some time. A hit or two on the CARN with its extensive armor are likely to incapacitate some of its weapon systems but not seriously impair the ships ability to fight. Obviously the more hits, the greater the collective damage. The CVLN and CVN, hopefully spared the worst by their placement at the far back of the layered spatial deployment chosen by Blue’s strike group commander, should be able to continue to function at close to normal capabilities, with the obvious proviso that any fires started do not prove difficult to bring under control.

So at the conclusion of the first round of the exercise, Red has achieved some significant, but not decisive damage with its massive 1,000 missile strike. So what does the Red Commander do next? If that is the sum of his assets, committing his modest long-range aircraft to anything other than continued harassing missions does not seem prudent. Blue’s obstructing carrier strike group has more or less survived and Red must now consider alternative means of achieving its objectives.

Unless Red, assumed to be a major East Asian land power, has utilized its substantial economic capability to construct a second wave of long-range missiles.

Red Force Commander

If so, then Red force commander, after a rapid but thorough review of the results of the first strike provided by his space-based reconnaissance assets decides to proceed with a pre-planned second strike. This time all of his available air assets will participate in the attack and Red Force commander does his best to coordinate another five minute time-on-target attack by hundreds of land based missiles and orders a much larger number of submarines to participate. Hopefully many of them will be able to evade Blue Forces SSNs and contribute at least some missiles from a multitude of different directions.

The intent here is to take advantage of the fact Blue Force will not have time to reload his ship borne missile tubes and in the intervening 30 minutes to an hour, only a few aircraft will have time to re-arm with AAW missiles. This will leave only the magazines of the railgun equipped ships with a significant amount of ammunition available for use.

Summation

At this point we will take leave of the exercise for with the results so far we are capable of making several conclusions.

1- Adding the various types of drones now available as well as the railgun, IN QUANTITY, to the fleet combined with appropriate doctrine adjustments, and flexible and carefully thought through battle plans means the fabled 1,000 missile strike can be survived by a typical carrier strike group.

2- This is particularly true of what most non-East Asian powers across the Eurasian landmass are likely to be able to field over the next few decades.

3- Adding a second CARN to the Western Pacific carrier strike group might well be a wise additional investment.

4- Several of the layers discussed above were deliberately provided with conservative success rates. The railgun itself may very well be able to operate, even at 65 miles, at much higher success rates. The ability to utilize our EEW and decoying assets could also provide significantly better results than estimated, as could the effects of dispersal.

5- Installing one or two railguns aboard the new CVNs as they are built looks to be an excellent idea. Consideration should also be given to installing one or two during refits, or during the refueling process, of our existing carrier assets.

In the next article we will discuss just why Congress and the American taxpayers should pay for all these additional UAVs, UUVs, Fire Scouts, buoys, railguns and the necessary ships to deploy them at sea.

Jan Musil is a Vietnam era Navy veteran, disenchanted ex-corporate middle manager and long time entrepreneur currently working as an author of science fiction novels. He is also a long-standing student of navies in general, post-1930 ship construction thinking, design hopes versus actual results and fleet composition debates of the twentieth century.

mmodation: The Best Option for Preventing War in the Taiwa

mmodation: The Best Option for Preventing War in the Taiwa