Guest post for Chinese Military Strategy Week by Chang Ching

Whether the newly-published Chinese Military Strategy white paper can be a credible source to decipher the military thinking of the People’s Liberation Army of the People’s Republic of China is an important question, one the author seeks to answer. Consider the following.

First, this publication known as the Chinese Military Strategy is generally misperceived as a publication of the Chinese Ministry of National Defense, when in fact it is in the form of a governmental white paper chiefly edited and published by the State Council Information Office (國務院新聞辦公室), headed by Jiang Jianguo. The First Bureau of the State Council Information Office is responsible for coordinating with other governmental agencies to edit and to develop these publications and satisfy inquiries submitted by the foreign media. More importantly, the State Council Information Office is also a government agency with another title within the Chinese Communist Party apparatus — the International Communication Office of the Communist Party of China Central Committee(中共中央對外宣傳瓣公室) — charged with conducting international propaganda. These facts provide context for judging the credibility of the document and its policy implications.

Second, this publication is not a legally binding document nor is it a document demanded by the PRC’s National People’s Congress and associated with the budgeting process. Neither is it a document defined by any legislative process, law, decree or statutory regulation in the PRC’s judiciary system. And it differs from the U.S. National Military Strategy, a document that must be consistent with the U.S. National Security Strategy, and other strategic guidance defined by the 1947 National Security Act and its descendants. This is not the case for the PRC’s seemingly-equivalent publications. The so-called defense white papers published by the State Council Information Office do not direct the PLA’s force planning and strategic thinking. Contents of these white papers are rarely quoted as the internal guidelines for directing military maneuvers or developing doctrine. These white papers are never treated as the basis for arguing defense policies or defending military strategic thinking in any domestic political arena. This suggests the irrelevance of these white papers within the PRC’s political decision-making process and provide reason for caution in other nations using them to understand the military strategy of the PRC and the PLA.

Third, the ratio between retrospective conclusions and prospective intentions may also reveal the value of this white paper. Generally speaking, most of the contents focus on conclusions associated with previous achievements and interpretations of their significance such as assistance given in rural and poor economic areas and law enforcement functions as described in the 2012 white paper on “The Diversified Employment of China’s Armed Forces.” As to declaring a plan for future direction, the statements of the white paper mainly follow existing practice such as the anti-piracy patrol mission. Although certain strategic challenges are explicitly pointed out, measures or policies for tackling these are basically repetition of previously-declared positions such as those regarding the situations in the East and South China Seas. Perhaps, though, it is optimistic to expect anything new may be exposed by a vehicle for international propaganda.

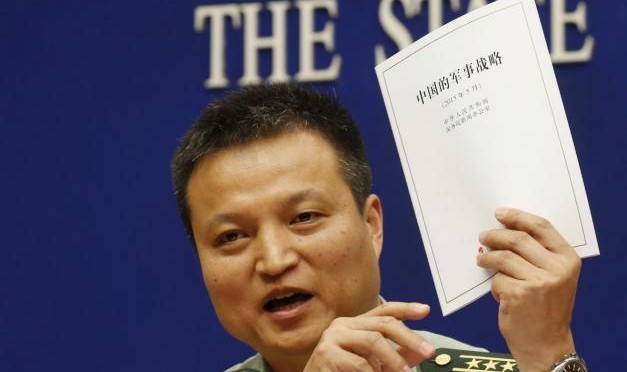

Last but not least, all readers should consider the respective prepared contexts for the introduction of the Chinese Military Strategy white paper and the 2015 U.S. National Military Strategy. The press conference introducing the U.S. strategy to the public was jointly hosted by the Secretary of Defense and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of the Staff. Comparatively, the PRC’s white paper was introduced at a press conference in the State Council Information Office and attended by several senior colonels. The 2015 US National Military Strategy was signed and publicized by a four-star general, the incumbent CJCS who will retire in September 2015. Since it is part of their political education, the members in the People’s Liberation Army well know the positions put forward in the Chinese Military Strategy white paper as it relates to their internal political decision-making process. But this is not a source for formal direction of military policy. It is no surprise that no significant discussion may occur within the Chinese military on this document except as a means to boost morale or boast of past success.

Of course, the content of the Chinese Military Strategy white paper is not totally without value. At least, readers may glean from it the areas of inquiry from the foreign press and policy critics that most concern the PRC’s State Council Information Office (or office for international propaganda). It may also be of use in understanding how the government of the PRC would like to shape the public image of the PLA. But the value of this document should never be overstated. Reading its content is a necessary precondition for understanding the PLA’s strategic thinking, but do not take it is as sufficient for thorough understanding.

Chang Ching is a Research Fellow with the Society for Strategic Studies, Republic of China. The views expressed in this article are his own.