Guest post for Chinese Military Strategy Week by Jan Stockbruegger

In May 2015 China presented its new Military Strategy white paper. The white paper, which appeared at a time of heightened tensions over land reclamations in the South China Sea, has triggered much debate and discussion. How should the strategy be interpreted, and how should policy makers respond to it? Does it demonstrate China’s expansionist and revisionist intentions? And does more need to be done to contain China’s rise as a super power? In this contribution to the debate I briefly summarize China’s new military strategy and reflect on it in the light of two diverging interpretations. I first argue that the strategy needs to be understood in terms of a deterrence logic that indicates the emergence of a security dilemma in the Asia-Pacific. I then offer a reverse interpretation that sees China’s military strategy as a move toward transparency and building trust and confidence. I conclude with some optimistic thoughts about how these two contradicting logics play into each other.

Maritime Rebalance and Military Modernization

China’s new military strategy is a very analytical document. It describes, analyses, and explains China’s perspective on international security, and it provides a frank and honest assessment of the threats and challenges the country faces. This includes “‘Taiwan independence’ separatist forces,” as well as the U.S. “’rebalancing’ strategy,” and its “military presence and its military alliances in this region.” China is particularly worried that some “external countries” – most likely the U.S. “are … busy meddling in the South China Sea affairs” and that a “tiny few maintain constant close-in air and sea surveillance and reconnaissance against China.” The strategy also refers to the dispute in the South and East China Sea – though it does not say so explicitly – when it notes that “some of China’s offshore neighbors take provocative actions and reinforce their military presence on China’s reefs and islands that they have illegally occupied.” China thus has to protect its “territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests.” Hence, the strategy argues the “traditional mentality that land outweighs sea must be abandoned,” and “great importance has to be attached to managing the seas and oceans.” China, it claims, will become a “maritime power” and “develop a modern maritime military force structure.” China intends to strengthen its navy, which “will gradually shift its focus … to the combination of ‘offshore waters defense’ with ‘open seas protection.’” The “preparation for military struggle,” in particular maritime military struggle, is central to China’s new military strategy.

Yet in the strategy China also claims that it does not have offensive military ambitions and will avoid armed confrontation and escalation. Its military philosophy is based on the idea of active defense, which holds that China “will not attack unless we [China] are attacked.” China will try to prevent crisis and, most importantly, “strike a balance between rights protection and stability maintenance.” The strategy also says that China supports collective security and embraces Confidence Building Mechanisms. Notably, China intends to deepen “military relations with the U.S. armed forces” to reflect the “new model of major-country relations” between the two states.

China’s new military strategy is to some degree ambiguous if not contradictory. It announces an ambitious military modernization program to protect its expanding interests while at the same time emphasizing its peaceful intention. This leaves room for interpretation. So how should one understand China’s military strategy? And how should the international community, in particular the U.S. and regional states, respond to it?

Deterrence and Security Dilemma

One way to interpret China’s military strategy is to look at what it says about the country’s military intentions and ambitions. From this perspective, China’s military modernization program appears threatening. It signals China’s long-term determination to dominate the Asia-Pacific and to use its expanding military capabilities to further narrow national security objectives. The strategy suggests that China will not accept Taiwan’s independence, will not abstain from its claims in the South China Sea, and will try to limit U.S. influence and military operations in the region. From this perspective, China is a threat that needs to be deterred. The U.S. in particular needs to do more to reassure its allies, to contain China, and to strengthen its predominant position in the Asia-Pacific.

This interpretation has significant implications for the regional security environment. It would eventually create a security dilemma, a situation in which, according to the eminent political scientist Robert Jervis, “the means by which a state tries to increase its security decreases the security of others.” It is easy to see how this would work. China feels its position is insecure, and it modernizes its military to deter potential aggressors. East Asian states and the U.S., on the other hand, feel threatened by China’s military build-up and behavior in the South China Sea, and they therefore strengthen their military capabilities to counter potential Chinese aggressions. Hence, even though neither side might want to risk conflict, their behavior increases exactly that risk. This dynamic reinforces rivalries, triggers intense security competition, and increases the likelihood of a confrontation between the world’s major military powers.

It is important to note that the security dilemma is not a fantasy or a distant future; its contours are already clearly visible, not only in China’s new military strategy and ongoing military modernization program, but also in the U.S. rebalance to Asia. Indeed, current U.S. defense debates are no longer about whether or not China needs to be deterred militarily; instead, analysts are already discussing specific military deterrence strategies (e.g., the Air-Sea Battle Concept, now renamed the Joint Concept for Access and Maneuver in the Global Commons). According to the new U.S. Seapower Strategy, 60 percent of U.S. Navy ships and aircraft will soon be deployed in the Indo-Asia-Pacific. Put differently, the Asia-Pacific security dilemma is an emerging reality, and China’s new military strategy further reinforces this trend.

It is important to note that the security dilemma is not a fantasy or a distant future; its contours are already clearly visible, not only in China’s new military strategy and ongoing military modernization program, but also in the U.S. rebalance to Asia. Indeed, current U.S. defense debates are no longer about whether or not China needs to be deterred militarily; instead, analysts are already discussing specific military deterrence strategies (e.g., the Air-Sea Battle Concept, now renamed the Joint Concept for Access and Maneuver in the Global Commons). According to the new U.S. Seapower Strategy, 60 percent of U.S. Navy ships and aircraft will soon be deployed in the Indo-Asia-Pacific. Put differently, the Asia-Pacific security dilemma is an emerging reality, and China’s new military strategy further reinforces this trend.

Transparency and Strategic Trust

Another way to interpret the strategy is to view it as a move towards military transparency, openness, and dialogue. In the strategy, China officially declares its long-term military interests and ambitions. It describes threats and challenges, outlines China’s plans for military modernization, and it also discusses China’s strategic new orientation. This might sound worrying and threatening to some security analysts. However, the strategy certainly does contribute to clarifying China’s military intention and explaining its rationale. Hence, a U.S. Defense Department spokesman commented in the New York Times that China’s new strategy “is an example of transparency” and “exactly the type of thing that we’ve been calling for.”

Military openness and transparency create trust and confidence among adversaries. They enables a better understanding of what each side wants, why they do the things they do, and how they might behave in the future. A military strategy hence also contributes to dialogue and mutual engagement. It allows actors to identify disagreements, develop joint interests, and reach common ground. Military dialogue does not resolve political conflicts, such as the islands disputes in the South China Sea, but it creates opportunities to avoid military escalation and to manage the security competition that such unresolved disputes produce.

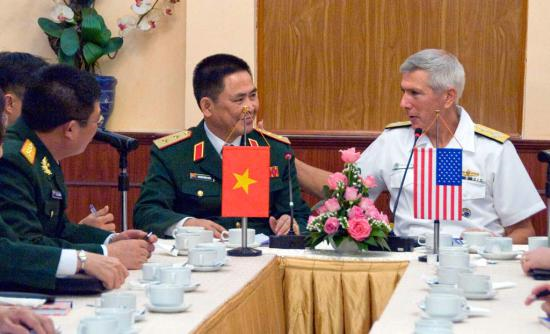

Such an Asia-Pacific military dialogue is already underway. In April 2014 regional naval representatives at the Western Pacific Naval Symposium signed a Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea. A similar document, a Memorandum of Understanding Regarding Rules of Behaviour for Safety of Air and Maritime Encounters, was signed by the U.S. and China in November 2014. Both documents, which are not legally binding, regulate military encounters at sea and seek to prevent incidents that could trigger military confrontations. The militaries of China and the U.S. also signed a Memorandum of Understanding on the Notification of Major Military Activities. With this document both sides “seek to foster greater comprehension of each other’s security policy.” They agree to engage in “regular exchanges of information related to major official publications and statements,” which includes “White Papers, strategy publications, and other official announcements related to policy and strategy.”

This is exactly what China has done with the publication of its new military strategy. Hence, from this perspective China’s military strategy does not reinforce the emerging Asia-Pacific security dilemma; rather, it is part of a pragmatic coping mechanisms aimed at managing this dilemma and de-escalating tensions in the region.

De-Escalating the Security Dilemma?

In this piece I have offered two interpretations of China’s new military strategy. I have argued that China’s military strategy contributes to a deterrence-based logic, and that it also de-escalates security competition. These two interpretations are certainly contradictory, but they are not mutually exclusive. China’s military strategy reflects a pragmatic double-strategy through which states seek to balance their security interests. On the one hand, China finds it necessary to deter potential adversaries militarily. On the other hand, however, it also relies on a peaceful international environment based on cooperative security arrangements. Yet whether the Asia-Pacific will manage to keep this balance is unclear. Regional disputes and conflicts are yet to be resolved, military expansion and modernization continue, and the emerging security order remains fragile. Are more efforts needed to manage the security dilemma and to ensure that security competition remains peaceful? This is exactly the question that stakeholders need to discuss jointly and as part of a sustained dialogue aimed at keeping peace and security in the face of increased geopolitical tensions and security competition in the region.

Jan Stockbruegger is a Research Assistant at Cardiff University and a graduate student in Political Science at Brown University. He is the lead editor of piracy-studies.org, a research and resource forum for maritime security studies. Jan can be contacted at stockbrueggerj@cardiff.ac.uk. The views expressed in this article are his own.