This publication originally featured at the National Maritime Foundation, and was republished with permission. You may read it in its original form here.

By Dr. Gurpreet S. Khurana

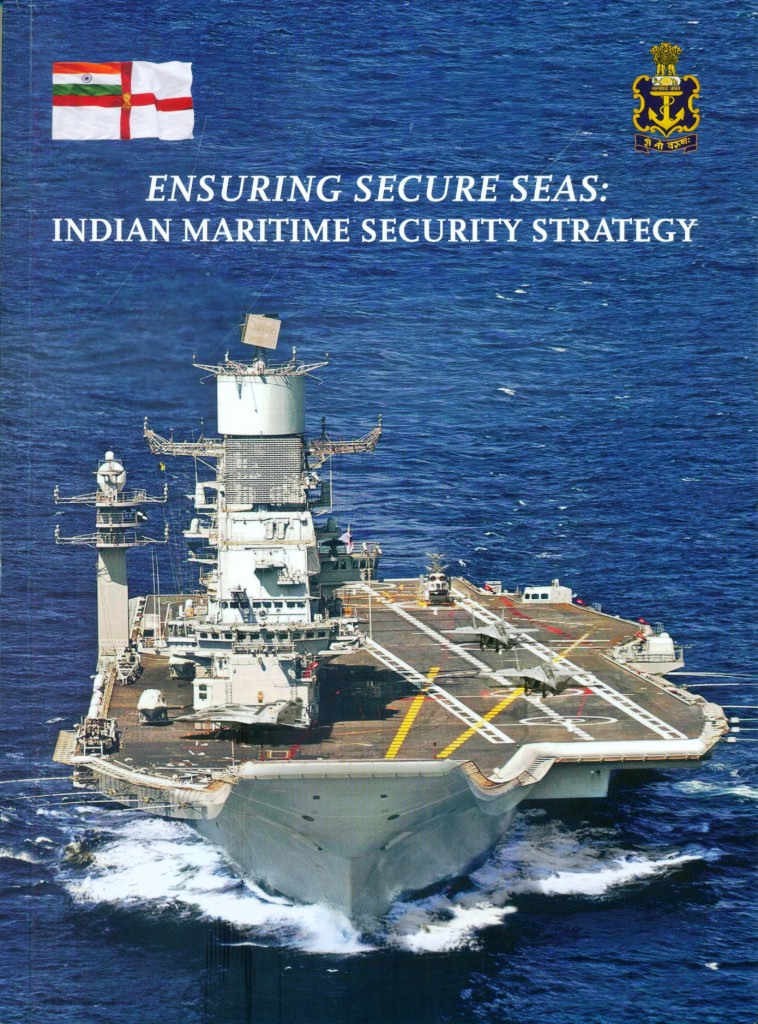

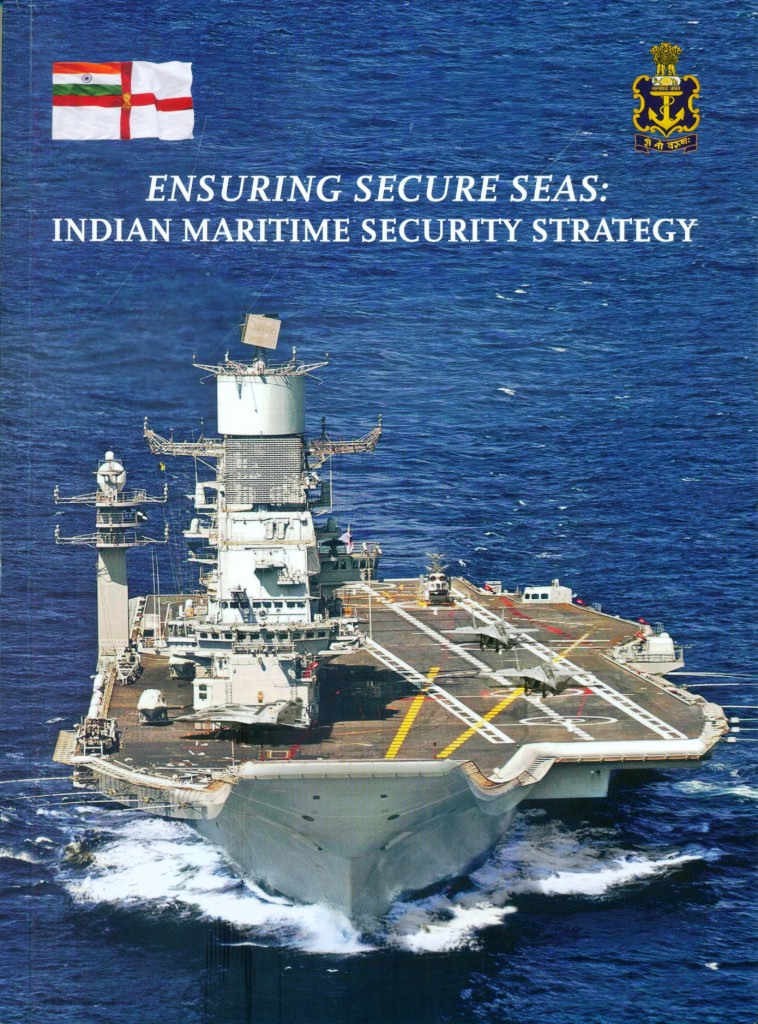

During the Naval Commanders Conference held in New Delhi on 26 October 2015, the Indian Defence Minister Shri Manohar Parrikar released India’s revised maritime-military strategy titled, ‘Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy’ (IMSS-2015). It supersedes the 2007 strategy document titled, ‘Freedom to Use the Seas: India’s Maritime-Military Strategy (IMMS-2007). This essay seeks to examine the salient features of the new strategy, including in comparison to IMMS-2007.

IMSS-2015 is the first strategy document released by the Indian Navy since the 26 November 2008 terrorist attack in Mumbai (26/11), when jihadi operatives well-versed in nautical skills used the sea route from Karachi to Mumbai, and carried out dastardly cold-blooded killings in India’s ‘financial capital.’ In wake of 26/11, the Indian government designated the Indian Navy as the nodal authority responsible for overall maritime security, including coastal and offshore security. The new strategy reflects the overwhelming imperative for the Navy to counter state-sponsored terrorism that may manifest in the maritime domain, and prevent a repeat of 26/11. It also addresses India’s response to other forms of non-traditional threats emanating ‘at’ and ‘from’ the sea that pose security challenges to ‘territorial’ India and its vital interests.

While 26/11 may have been among the major ‘triggers’ for India to review its maritime-military strategy, IMSS-2015 clearly indicates that proxy war through terrorism has not prevented India to adopt an outward-looking approach to maritime security. The new strategy dilates the geographical scope of India’s maritime focus. Ever since the Navy first doctrinal articulation in 2004—the Indian Maritime Doctrine, 2004, which was revised in 2009—India’s areas of maritime interest have been contained within the Indo-Pacific region, with the ‘primary area’ broadly encompassing the northern Indian Ocean Region (IOR). IMSS-2015 expands the areas of interest southwards and westwards by bringing in the South-West Indian Ocean and Red Sea within its ‘primary area;’ and the western Coast of Africa, the Mediterranean Sea and “other areas of national interest based on considerations of Indian diaspora, overseas investments and political reasons” within its ‘secondary area’ of interest.

IMSS-2015 is merely an expression of intent of the Indian Navy to engage with the countries and shape the maritime environment in these areas. Nonetheless, the Navy’s multi-vectored and expanding footprint in recent years through overseas deployments clearly indicates that the maritime force is developing the capabilities to implement the intent.

India has always maintained that the International Shipping Lanes (ISL) and the maritime choke-points of the IOR constitute the primary area of interest. However, the new strategy goes beyond IMMS-2007 to include two additional choke-points: the Mozambique Channel and Ombai-Wetar Straits, which are strategically located at the far end of the south-western and south-eastern Indian Ocean (respectively). Through a formal ‘recognition’ of these choke-points, IMSS-2015 not only reiterates the embayed nature of the Indian Ocean, but also highlights—albeit implicitly—the ocean’s geo-strategic ‘exclusivity’ for India.

IMSS-2015 also clarifies India’s intent to be a ‘net security provider’ in its areas of interest. The concept of ‘net security’ has hitherto been ambiguous and subject to varied interpretations. It is, therefore, refreshing to note that the document defines the concept, as “…the state of actual security available in an area, upon balancing prevailing threats, inherent risks and rising challenges in the maritime environment, against the ability to monitor, contain and counter all of these.” In the process, India’s role in this context also stands clarified. India seeks a role as a ‘net security provider’ in the region, rather than being a ‘net provider of security’ as a regional ‘policeman.’

IMSS-2015 expounds on India’s strategy for deterrence and response against conventional military threats and the attendant capability development, sufficiently enough for an unclassified document. In doing so, it may be inferred that the concept of ‘maritime security’—at least in the Indian context—operates across the entire spectrum of conflict. The new strategy attributes this to the “blurring of traditional and non-traditional threats…(in terms of their) sources, types and intensity…(necessitating) a seamless and holistic approach towards maritime security.” Notably, in contrast, for the established naval powers of the ‘western hemisphere,’ the usage of the concept of ‘maritime security’ is limited to ensuring security at sea against non-traditional threats, including those posed by non-State actors.

Although the epithet of India’s maritime-military strategy has changed from “Freedom to Use the Seas” (IMMS-2007) to “Ensuring Secure Seas” (IMSS-2015), ‘freedom of seas’ for national purposes remains inter alia a key objective of the current strategy, which is sought to be achieved through the attainment of a more ‘encompassing’ end-state of ‘secure seas.’

India’s role as a ‘net maritime security provider’ in the region is not only its normative responsibility as a regional power, but is closely interwoven with the nation’s own economic growth and prosperity. The ‘roadmap’ in IMSS-2015 provides a direction to the Navy to play this role as an effective instrument of the nation’s proactive foreign policy, in consonance with the ongoing endeavour of its apex political leadership, and echoes the enunciation of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s vision of “SAGAR” (Security and Growth for All in the Region). However, it remains to be seen how India’s navy would effectively balance the rather conflicting national security priorities of ensuring territorial defence across its oceanic frontiers versus providing ‘net maritime security’ in its regional neighbourhood.

Captain Gurpreet S Khurana, PhD is the Executive Director, National Maritime Foundation (NMF), New Delhi. The views expressed are his own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Indian Navy, the NMF or the Government of India. He can be reached at gurpreet.bulbul@gmail.com.