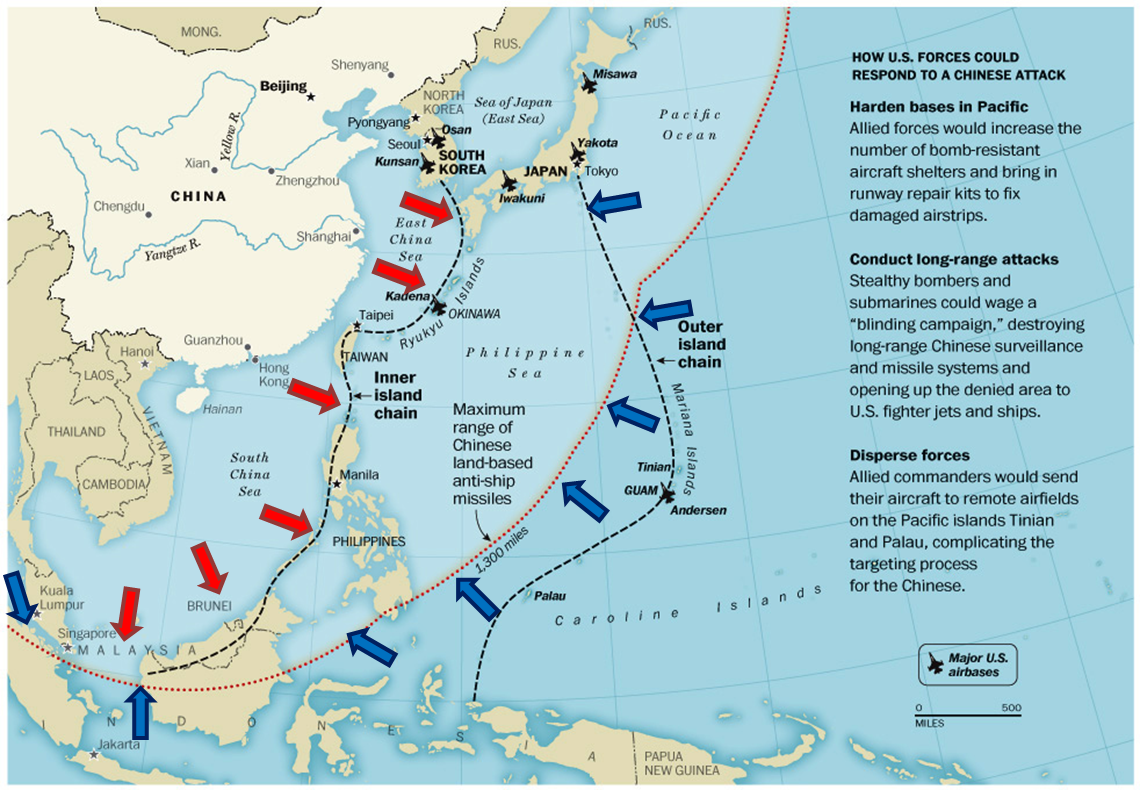

One does not need to look to far into the history of maritime operations to discern a pattern of importance: you are always attempting to locate and fix your adversary in order to destroy them, while simultaneously, your adversary is attempting the same. The sea provides a certain ubiquity that cannot be reduced in any aim of contestation by the other domains or more directly via control. Yet, when one considers the problems of a domain, there is interplay of practical constraints, which are: tactics, technology, organization, and doctrine. Here, I would briefly like to focus the reader’s attention on the latter item—doctrine—although there will be references to the other aspects throughout. Specifically, I would like to highlight the importance of the 1943 Pacific Fleet Tactical Orders and Doctrine, also known as PAC-10, and its possible relevance to the Air -Sea Battle Concept (ASBC).

The proper usage of naval aviation, and especially its carriers, has been debated since the days of Eugene Ely’s first flights launching and recovering on rudimentary aircraft carriers in 1910-11. During the interwar years between the World Wars there was vast variance in doctrine recursively revised as result of technological improvements, experimentation, and exercises. Doctrinal development and revision did not stop there, even as World War II unfolded in the Pacific, but in 1943, PAC-10 provided both timely clarity and flexibility to commanders in that theater.

Prior to World War II, specifically in 1937, U.S. Navy Captain Richard K. Turner presented a lecture at the Naval War College titled “The Strategic Employment of the Fleet,” and produced an associated pamphlet entitled “The Employment of Aviation in Naval Warfare.” While his lecture maintained a decisively Mahanian tenor, Turner’s pamphlet stated that “nothing behind the enemy front is entirely secure from observation and attack,” which provides rhyme to today’s “attack in-depth” in the ASBC.

According to Thomas Hone, before and during 1942, aircraft carrier doctrine focused upon three things: raids, ambushes, and covering invasion forces. Where raids attempted to fix Japanese forces in particular areas, ambushes would seek to attrit Japanese ability to control the seas, and invasion forces sought to add cumulative strategic effect by maneuvering amphibious forces to occupy specific islands for follow-on usage against Japan by joint forces.

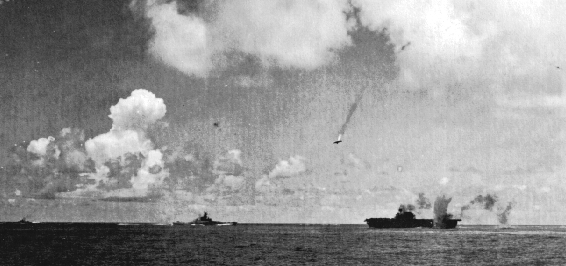

The major shortfall of the doctrinal precursors to PAC-10 was that, while useful for thinking (and spurring debate) about the control of the maritime domain and maximizing the contest of the air and land domains, they fell short of effectively suggesting to commanders how to best employ aircraft and carriers operationally in task forces. This shortfall came into clear focus during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands. Enter the innovation of PAC-10.

In his Naval College Review article entitled, “Replacing Battleships with Aircraft Carriers in the Pacific in World War II,” Thomas Hone described PAC-10 as the following:

PAC-10 was a dramatic innovation. It combined existing tactical publications, tactical bulletins, task force instructions, and battle organization doctrine into one doctrinal publication that applied to the whole fleet. Its goal was to make it “possible for forces composed of diverse types, and indoctrinated under different task force commanders, to join at sea on short notice for concerted action against the enemy without interchanging a mass of special instructions.” PAC-10’s instructions covered one-carrier and multicarrier task forces, and escort- or light-carrier support operations of amphibious assaults. It established the basic framework for the four-carrier task forces—with two Essex-class ships and two of the Independence class—that would form the primary mobile striking arm of the Pacific Fleet. However, it did this within the structure of a combined naval force, a force composed of surface ships— including battleships and carriers….

PAC-10 solved two problems. First, “the creation of a single, common doctrine allowed ships to be interchanged between task groups.” Second, “shifting the development of small-unit tactical doctrine to the fleet level and out of the hands of individual commanders increased the effectiveness of all units, particularly the fast-moving carrier task forces.”

PAC-10 was truly a watershed moment in operationally considering complement of sea and air capabilities en masse for strategic effect. It moved beyond the oversimplified “duty carrier” (self defense combat air patrol and/or antisubmarine warfare) and “strike carrier” (maritime strike and/or support to land forces ashore) concepts. “Whether a task force containing two or more carriers should separate into distinct groups . . . or remain tactically concentrated . . . may be largely dependent on circumstances peculiar to the immediate situation,” the doctrine stated, where “[no] single rule can be formulated to fit all contingencies.” Unsurprisingly, context was key in the application of PAC-10. Ultimately, PAC-10 focused commanders upon unified effort by maximizing strike, whether that is raids, ambushes, or amphibious attack, while also mitigating the risk of destruction via advanced detection.

There are several similarities and differences that need to be drawn from PAC-10 to now for consideration with the ASBC. First, and most importantly, the doctrinal concept did not and could not divine strategic victory. It was neither easy to accomplish, nor did it ignore the necessary requirement for termination to be chosen by the adversary, and furthermore, many heroically died in its use. However, and this is a fundamental truth that cynical detractors of the ASBC chose to ignore, many more would have died had PAC-10 not been developed. Rather, and it was apparent to them at the time, PAC-10 provided commanders an improved tool for use towards strategic effect. So say we all with concern to the ASBC.

Second, and almost as important as the first comparison, PAC-10 was a doctrinal concept that entailed warfare. And although there were no further constraints against escalation in World War II, PAC-10 provided considerable potential for strategic effect. How such an improved tool is used is a matter of decision in either the march towards war or during warfare to be made by policy makers via strategic negotiation, careful signaling, and demonstration. One mustn’t deny the value of PAC-10, or the doctrinal aspects of the ASBC, simply because of an over-wrought conflation of a tool with its purpose.

Tactical proficiency and operational effectiveness, are best measured in peacetime from the potential ideal, with the acknowledgment that fog and friction will chew away at that ideal in exercise and practice; whereas, strategic effect is best measured relative to a status quo and desire for continued advantage. The ASBC is focused clearly upon the former, and will only contribute limited strategic effect towards the latter. Clear-eyed strategists must admit that limited effect may be sufficient, but then again it may not as determined by context. However, neither is cause for rejection of an operational concept like the ASBC as a useful tool.

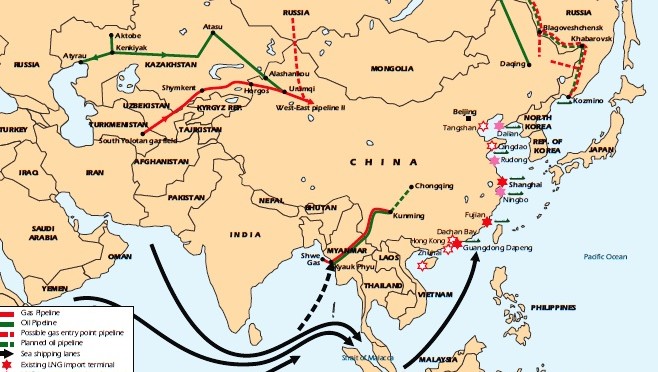

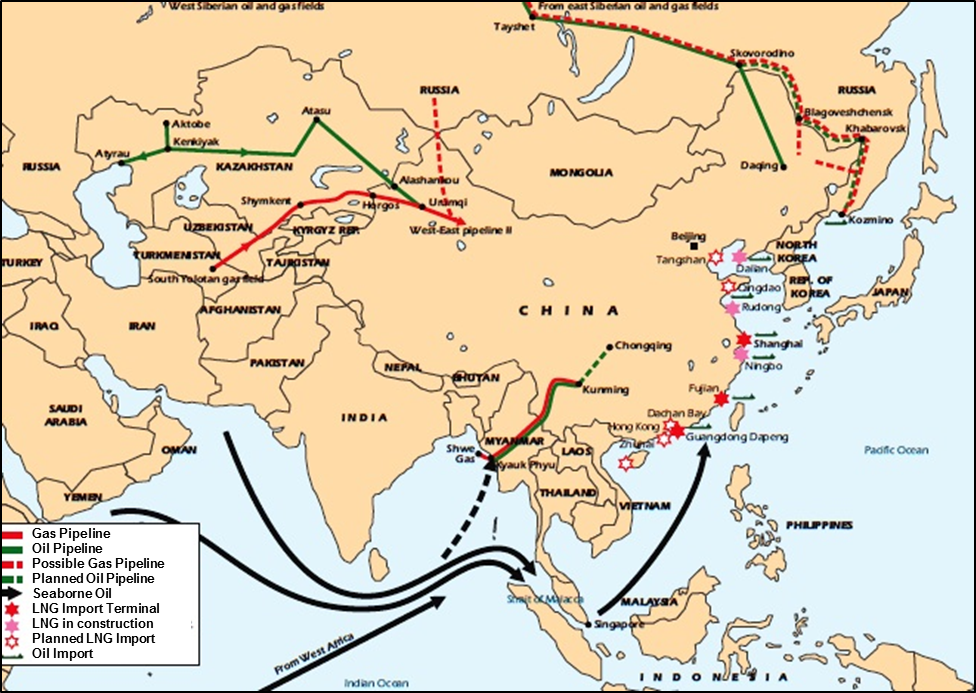

Third, the tactical combination of air and sea forces in PAC-10 combined with amphibious land attack, contributed to numerous successes in the Pacific. Similarly, a balanced ASBC, that includes a naval economy of force (relative to World War II), along with concomitant of air and land component forces, will create a complicated problem for mounting a successful defense at any one place; just like the PAC-10 doctrine similarly achieved at the Marcus, Gilbert, and Marshall Islands and elsewhere in World War II. In recent, yet more modern times, fleet defense may have been sufficient with only carrier-based aircraft. But at present, both the smaller number of available carriers, an inability to replenish weaponry while underway in the current submarine and destroyer forces, not to mention the basic prudence of joint capability, means that combined arms by way of only one service is no longer a prerogative that the United States can afford to ignore. Similar to the PAC-10 doctrine of yore, the modern ASBC doctrine of the near-future must be able to more effectively balance all joint forces. Needless to say, even if service prerogative still dominates, using carrier aviation alone will diminish strike potential in fleet defense. Dissimilar to the PAC-10 doctrine of yore, the modern ASBC doctrine of the near future must effectively raise its doctrine above that of the fleet and into the joint realm. This means finding effective ways to use Air Force assets and Army assets in roles of fleet defense and sea control just like disparate forces from various carriers in PAC-10 effectively formed a coherent and formidable task force.

As a guide for the ASBC, the interoperability between air forces (of all types) and land forces (of both traditional and amphibious focus) have benefited from the development of joint doctrine from the combined capabilities and tactics of the Air Land Battle Concept (ALBC). Despite some cynical “easy war” views of ASBC, the ALBC provides a useful scorecard for joint action. The latter has proven unquestionably effective in both mission success and preserving lives in battle from Operation DESERT STORM to the current fight in Operation ENDURING FREEDOM; but its equal in terms of joint combined effect does not yet exist to the same fidelity in the maritime and littoral environments. Our ability to project power, achieve strategic effect by joint combined arms, and experiment with doctrine costs relatively little compared to operational failure. Instead of playing politics — actual joint thinking costs nothing. After all, history and pragmatic thinking proves the obvious, you can’t finish without access.

As a guide for the ASBC, the interoperability between air forces (of all types) and land forces (of both traditional and amphibious focus) have benefited from the development of joint doctrine from the combined capabilities and tactics of the Air Land Battle Concept (ALBC). Despite some cynical “easy war” views of ASBC, the ALBC provides a useful scorecard for joint action. The latter has proven unquestionably effective in both mission success and preserving lives in battle from Operation DESERT STORM to the current fight in Operation ENDURING FREEDOM; but its equal in terms of joint combined effect does not yet exist to the same fidelity in the maritime and littoral environments. Our ability to project power, achieve strategic effect by joint combined arms, and experiment with doctrine costs relatively little compared to operational failure. Instead of playing politics — actual joint thinking costs nothing. After all, history and pragmatic thinking proves the obvious, you can’t finish without access.

Need a new idea? Try an old one. Take a look at Pacific Fleet Tactical Orders and Doctrine (PAC-10), and you might see the future of a balanced Air Sea Battle Concept doctrine.

Major Rich Ganske is a U.S. Air Force officer, B-2 pilot, and weapons officer. He is currently assigned to the U.S. Army Command and General Staff Officers Course at Fort Leavenworth. These comments do not reflect the views of the U.S. Air Force or the Department of Defense. You can follow him on Twitter at @richganske and he blogs via Medium at The Bridge and Whispers to a Wall. Tip of the hat to “Sugar” for the reference to an old idea (or book).