By Vice Admiral Ignacio Villanueva Serrano, Operation Commander, EU NAVFOR ATALANTA

The waters surrounding the Horn of Africa and the Western Indian Ocean are a vital confluence of global and local interests, serving as essential conduits for international trade, energy security, and the livelihoods of coastal communities.

These maritime spaces, encompassing strategic choke points like the Bab el-Mandeb strait, are both a lifeline and a point of vulnerability, confronted by threats such as piracy, illegal fishing, and transnational organized crime. In an era of increasing international competition and emerging security challenges, non-African states are indispensable in supporting African regional maritime security, working alongside local actors to safeguard these critical domains.

As the Operation Commander of EU NAVFOR ATALANTA, I offer insights into how external and regional stakeholders collaborate to pursue shared maritime security objectives, drawing on our operational experience and acquired expertise.

The Global and Local Significance of African Waters

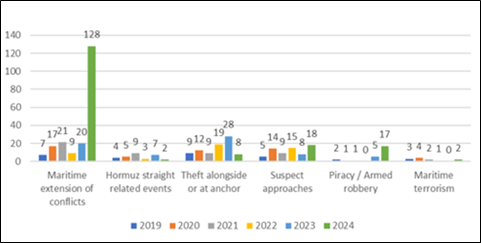

The Western Indian Ocean is a global commons, linking continents and enabling the flow of goods, energy, and people. Its strategic importance is amplified by chokepoints like the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, which are critical to fuel and food security for global shipping and regional stability. These waters are pivotal to international supply chains and the economic well-being of African littoral states, yet they remain under threat. In the Horn of Africa, piracy persists as a latent risk, with Pirate Action Groups (PAGs) still active in Somalia despite significant reductions since its peak over a decade ago. Recent incidents highlight a resurgence, underscoring the need for continued vigilance. Meanwhile, attacks on sea lines of communication in the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, and Arabian Sea by groups employing sophisticated weaponry, such as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), further complicate the security landscape, impacting freedom of navigation and global trade. Beyond piracy, transnational organized crimes, such as narcotics trafficking, human smuggling, and illegal fishing, pose additional challenges, compounded by arms smuggling networks that supply advanced weapons, often transported via maritime routes from distant origins.

The interconnected nature of these threats demands a robust, collaborative response where non-African states, particularly through the European Union, provide essential support to regional efforts. Recent assessments indicate a low piracy threat in the Gulf of Aden and parts of the Somali Basin, though a realistic possibility of attacks persists. Conflict-related threats in the Red Sea remain severe for vessels linked to specific nations, reflecting the dynamic risk environment we navigate.

The Contribution of Non-African States

Non-African states have engaged decisively in this complex environment, motivated by strategic, economic, and humanitarian imperatives. EU NAVFOR ATALANTA, launched in 2008, is a testament to this commitment. Initially established to counter Somali-based piracy, our operation has evolved into a broader contributor to maritime security, with a mandate extended until February 2027. This updated mandate encompasses protecting merchant shipping and World Food Program (WFP) vessels, countering weapons and narcotics smuggling, and monitoring illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, reflecting the EU’s enduring commitment to stability in the region. Our achievements—reducing piracy through naval patrols, maritime surveillance, and legal prosecutions—demonstrate the tangible impact of external involvement.

Throughout our mission, we have handed over 177 suspected pirates for trial across jurisdictions including Kenya, Seychelles, Mauritius, and EU member states, with 145 successfully convicted. In a particularly active year, we transferred dozens of pirates captured during multiple incidents, reflecting a robust deterrent effect. The knowledge that apprehension leads to prosecution and lengthy sentences in regional or international jurisdictions discourages pirate activity, contributing to a decline in attacks over time. Our success rests on robust cooperation with military partners, a strong military-industry partnership, advanced maritime security architecture, and effective defense diplomacy.

EUNAVFOR Operations and associated contributors deploy naval assets, such as frigates, patrol vessels, and maritime patrol aircraft, alongside helicopters and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to patrol key areas like the South Somali Basin, Gulf of Aden, Arabian Sea, and Red Sea. Recent operations have seen vessels under our operational control conduct joint activities with allied task forces, share intelligence on smuggling routes, and enhance local maritime capabilities through engagements with regional navies like Kenya’s. Maritime patrol aircraft, flying sorties along the Somali coast and the Red Sea, bolster our surveillance. At the same time, port visits to strategic locations like Mombasa, Victoria, Salalah, and Djibouti facilitate maintenance, replenishment, and coordination.

Our cooperation with INTERPOL further reinforces information exchange. In matters relating to illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (IUU) within Somalia’s Exclusive Economic Zone, coordination is maintained directly through INTERPOL’s National Central Bureau in Somalia. This intelligence link enhances our ability to detect and respond to transnational maritime crimes with international reach, amplifying our operational impact.

The transformation of our Maritime Security Centre Indian Ocean (MSCIO) into a modernized platform, completed with upgrades set for 2025, features four integrated applications—Registration, Alert, Analysis, and Blog—bolstering situational awareness. The MERCURY platform is central to this evolution, our primary tool for secure, real-time information sharing with other naval partners and maritime law enforcement agencies in the Western Indian Ocean.

An agreement with the International Maritime Organization (IMO) provides access to Long Range Identification and Tracking (LRIT) data from over 80 Flag States, significantly strengthening our tracking capabilities. As of early April 2025, over 1,000 cargo and tanker vessels are registered within our voluntary reporting area, with nearly 50% of daily entrants actively participating, underscoring industry trust in our framework. Advanced data collection and analysis, leveraging automatic identification system (AIS), LRIT, and satellite imagery, remain pivotal in tracking vessels and monitoring threats, from piracy to conflict-related risks in the Red Sea.

Partnership Between External and Local Actors

Effective maritime security hinges on collaboration between non-African and African stakeholders, harmonizing external expertise with regional ownership. Our partnership with the shipping industry exemplifies this synergy, with over 4,200 cargo and tanker vessels operating within our voluntary reporting area as of early April 2025. Our maritime security center fosters trust through vessel registration and incident reporting, supported by a modernized system with intuitive interfaces and offline capabilities. A standardized reporting framework enhances communication and interaction with the shipping industry, making the registration and incident reporting processes more streamlined and efficient.

The Indo-Pacific Regional Information Sharing (IORIS) platform, a non-binding yet widely adopted information-sharing mechanism governed by a Steering Committee, is a key enabler of multinational maritime cooperation.

EUNAVFOR ATALANTA has played a leading role in shaping IORIS by participating in thematic and geographic Community Areas (CAs), including search and rescue, pollution response, and maritime interdiction. Through initiatives like the ALDABRA II exercise and training programs in Seychelles, IORIS has demonstrated its potential as a unifying platform. Initial lack of coordination with other maritime coordination entities like the United Kingdom Maritime Trade Operations (UKMTO) has been resolved through persistent engagement, achieving unprecedented cooperation that benefits the naval community.

The Shared Awareness and Deconfliction (SHADE) Forum has evolved into a groundbreaking platform that brings together naval forces from across the globe alongside industry stakeholders. Far beyond a series of routine meetings, SHADE represents a genuine operational partnership where commercial shipping actors actively participate and hold an equal voice in shaping maritime security decisions.

We have also formalized cooperation with regional maritime centers such as MSC Oman, establishing protocols for real-time information exchange, expertise sharing, and coordinated responses. These bilateral agreements underscore our commitment to empowering regional actors and reinforcing the collaborative fabric of maritime governance in the Western Indian Ocean.

Private maritime security companies (PMSCs) serve as force multipliers, providing deterrence and real-time intelligence. Their tactical presence on vessels, tested by PAGs, remains effective, though adaptations to counter sophisticated threats like drones and missiles through enhanced crew training and citadel procedures strengthen our collective response.

Joint operations with allied task forces like the Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) further amplify our reach. Regional frameworks amplify this collaboration, with African navies committing to joint efforts to protect maritime territories. ATALANTA actively supports the Djibouti Code of Conduct (DCoC), adopted in 2009 under IMO facilitation and expanded via the Jeddah Amendment in 2017 to address broader threats like trafficking and IUU fishing. Our participation in DCoC high-level meetings and training workshops enhances regional capacity and coordination in the Western Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden. Exercises with regional partners, such as Kenya, Djibouti, and Seychelles, bolster interoperability and local capacity through maritime interdiction training and key leader engagements, reinforcing stability.

Finally, I just recently finished a trip to India to improve the operational coordination in the area, to provide adequate points of contact (POCs) for both ATALANTA and Indian Navy Maritime Security Centers, and to set the scenario for an international maritime exercise that helps to recreate possible engagements at sea and ease future cooperation.

Adapting to Regional Realities

Our experience underscores that uniform solutions are impractical. Somalia’s fragile governance and absent navy necessitate direct intervention authorized by international resolutions. We adapt by focusing on trust-building, regionally led cooperation, and a robust legal finish. Advanced alert and analysis tools tailor responses to local threats, while efforts to enhance judicial capacity in regional states ensure effective prosecution.

Somalia’s onshore instability, marked by militant activities targeting supply lines and military operations in regions like Lower Shabelle and Bari, indirectly influences maritime security. However, direct threats to our assets remain highly unlikely. Yemen’s conflict, with resumed Houthi activities following airstrikes, heightens risks in the Red Sea, though merchant shipping has seen no recent attacks as of early April 2025.

The resurgence of piracy, distinct from Red Sea threats, requires tailored legal and operational frameworks. Economic motives, illegal fishing, and political instability fuel this resurgence, with a moderate threat persisting in parts of the Somali Basin and Gulf of Aden. Recent cases in territorial waters, often involving fishing vessels, pose unique challenges due to legal and jurisdictional complexities, yet our agile response, deploying assets within 48 hours, mitigates risks.

Looking ahead, I anticipate one or two piracy incidents in the near term, a manageable level given our current capabilities, though uncertainties around local licensing and corruption complicate our understanding.

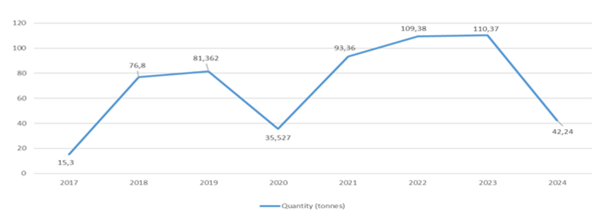

Tackling Root Causes and Future Challenges

Non-African states address maritime insecurity’s root causes, though challenges persist. In Somalia, piracy’s decline reflects naval deterrence and best management practices, yet poverty, instability, and organized crime endure. Capacity-building initiatives strengthen law enforcement, constrained by onshore conflicts and competing priorities. Our narcotics seizures, totaling nearly 16,000 kilograms, including over 3,000 kilograms of hard drugs like heroin, disrupt trafficking networks. However, many suspects are released due to jurisdictional limits, highlighting the need for broader legal frameworks.

Our operation has shifted from focusing solely on counter-piracy to a broader maritime security role, contributing to the Western Indian Ocean’s stability. Resource constraints limit full implementation, but focused operations targeting illegal fishing yield actionable insights. Future enhancements to our maritime security platform, including AI integration and expanded vessel tracking, will improve threat detection and address adaptive risks from smuggling networks and conflict spillovers. Sustained funding and mandate adjustments remain essential to counter emerging challenges.

Conclusion

Non-African states are vital partners in African regional maritime security, providing resources, expertise, and coordination that complement local efforts. EUNAVFOR ATALANTA’s engagement, enhanced by modernized tools, industry partnerships, and capacity-building, secures critical sea lanes. Our success depends on trust, shared awareness, and tailored approaches. Naval coordination, PMSCs, legal innovation, and platforms like MERCURY and IORIS bridge the gap between external and local actors. As threats evolve, from piracy’s resurgence to sophisticated attacks, sustaining these partnerships, leveraging advanced capabilities, and addressing onshore drivers remain imperative to ensure that this connected ocean fosters stability rather than insecurity. Our strategic achievements position EUNAVFOR ATALANTA embedded in the regional maritime security architecture with high international recognition and represent a tangible tool for the EU’s objectives and interests in the West India Ocean.

VADM Ignacio Villanueva Serrano has been the Operation Commander of Operation Atalanta, EU NAVFOR since November 2023. A graduate of the Spanish Naval Academy, he began his career as a Naval Aviator, later commanding several naval platforms before becoming a staff officer in the International Relations Department at the Spanish Navy headquarters. He has extensive NATO experience in both operational and staff officer defense planning, NATO expeditionary operations and the Combined Force Maritime Component Commander for NATO Flag Officers. VADM Villanueva earned a Master of Arts in National Security and Strategic Studies from the US Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island and has been a Professor at the High Defense Studies Center in Madrid, Spain.

Featured Image: EUNAVFOR Atalanta Joint Sea Activity, supporting UNODC’s Global Maritime Crime Programme (GMCP) and Somali Fisheries Enforcement officers, as part of UNODC organised training activity Ex Sea Spirit in support of UNSCR 2662/2022. (EUNAVFOR photo)