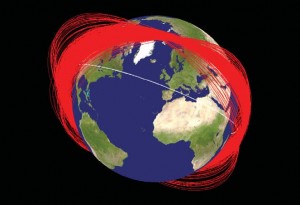

The United States is undeniably reliant on its robust space-based architecture for both military and commercial operations. Having invested heavily in space for more than forty years now, the United States enjoys what RAND’s Benjamin Lambeth calls “asymmetric advantages” [1] commensurate with that investment. Unprotected and largely unaddressed by international legislation, however, these advantages could quickly become “asymmetric vulnerabilities” were they disabled, destroyed, or otherwise disrupted. The threat to these systems from Anti-Satellite technologies, specifically dual-use anti-ballistic missile (ABM) platforms, is becoming increasingly more acute as more nations develop the capability to disrupt and/or deny the U.S. and its allies use of its extensive space constellation. In order to preserve the favorable balance of power in space it currently enjoys, the United States should lead the development of legally binding international legislation restricting the use of anti-satellite weapons. Such legislation would not only protect the United States’ ability to draw on its considerable space investment, but also protect the peaceful use of and access to space as a global common.

The United States’ withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) treaty in 2002 opened the door for unfettered development and testing of anti-ballistic missile technologies, some of which retain ASAT capabilities with only minor modifications. Between 2007 and 2008, China and the United States both conducted tests of operational, modified ABM direct-ascent anti-satellite weapons.

The PRC’s 2007 use of a DF-21 modification dubbed SC-19 to destroy their FY-1C weather satellite in High Earth Orbit (HEO) created a cloud of space debris projected to remain in orbit for decades. Shortly thereafter, the United States deployed an SM-3 from the USS Lake Erie to destroy a decaying NRO satellite in low-earth orbit. The 2008 test was successful, and though it didn’t create a cloud of space debris like SC-19, the combination of these tests and following PRC tests (none of which, it should be noted, were against a ‘space object’ as defined by UNOOSA) re-ignited the discussion of the Prevention of Arms Race in Outer Space (PAROS), dormant since the height of the Cold War.

Existing and proposed legislation on the matter is either too narrowly focused or insufficient in scope to effectively manage the question of PAROS or assure continued access to space as a global common. The United Nations’ Outer Space Treaty, first introduced in 1966, is, along with four other UN treaties and agreements, the extent of existing international legislation on the use of space. Broad and permissively non-specific, the cumulative weight of these treaties and agreements does not serve to affect the development of terrestrially-based ASAT weapons, only assigning responsibility for the damage such a weapon would inflict – a concept totally beside the point were such a weapon to be used operationally. The laudable EU Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities, now in its third draft iteration, is painted in similarly broad-strokes, voluntary, and has thus far received a lukewarm reception from the wider international community. Russia and China have cooperatively presented working papers in 2002 and 2008 to the Conference on Disarmament (CD) concerning the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space and of the Threat or Use of Force against Outer Space Objects (PPWT). The Sino-Russian drafts are unattractive to the United States due to their ambiguity and lack of clear diction on dual use systems like SC-19. Restrictions on merely notional co-orbital systems combined with ambiguous language on operational dual-use technologies would be cold comfort to the United States, as its primary interest in space lies in the protection of the status quo, in which it enjoys tremendous advantages.

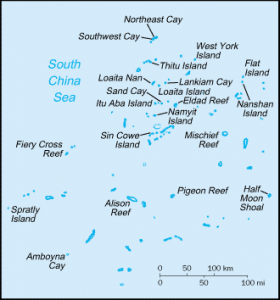

The United States’ best opportunity to protect this status quo is to take the lead in developing meaningful, specific international legislation restricting not only potential co-orbital weapons but existing dual-use ASAT capabilities as well. The alternative, going on the offensive and stoking the flame of an arms race in space, is too costly both in terms of investment and risk to the continued use of space as a peaceful, accessible global common. At the very least, the financial commitment necessary for continued development of offensive and defensive space-based technologies presents a tremendous cost in an increasingly fiscally restrained environment. This investment could be better applied to the modernization of rapidly-aging air-breathing platforms that will prove essential to the United State’s ability to maintain dominance over near-peer and proto-peer competitors (focusing on counter-A2AD platforms in the Pacific immediately jumps to mind). Further testing of kinetic-kill weapons like the one used to destroy China’s FY-1C weather satellite will create celestial litter that, depending on the orbit of the target, pollute space and pose potential hazards to surrounding constellations, threatening all space stakeholders equally.

Lastly, though a “space Pearl Harbor” (to borrow a phrase from the Rumsfeld commission) may seem like an unlikely prospect after only two verified ASAT tests, it isn’t difficult to imagine a scenario in which a demonstrative ASAT launch by the PRC resulting in damage to or disruption of the United States’ overhead constellation could rapidly escalate already heightened tensions, further underscoring the utility of international legislation restricting the use of these weapons.

As none of the existing proposals on ASAT legislation are “just right,” what, then, would the United States’ best-case scenario legislation look like? Three pillars of such a proposal might include the following: a clear, discrete definition of what constitutes space, restrictions on dual use technologies being used in an ASAT capacity, and robust verification and reporting regimes. The combination of the first and second pillars (along with the fact that ABM weapons will always have the ability to act in an ASAT capacity) would provide a fail-safe for the U.S. going forward and address critics of ASAT-bans who argue that national security interests could be put in jeopardy by hostile satellites in the future. The United States’ ever-increasing dependence on overhead assets makes cogent and comprehensive action on space an absolute priority for future administrations. The prohibitive cost of engaging in an arms race in outer space (money, this author would argue, that would be much better spent on maintaining terrestrial dominance over near-peer competitors) as well as the risk to peaceful space operations and common access to space as a global common provide compelling reasons for the US to definitely take the lead on anti-ASAT legislation and, in doing so, protect their primacy and currently uncontested advantages in space.

[1] Lambeth, B. (2003). Mastering the ultimate high ground next steps in the military uses of space. Santa Monica, CA: RAND, Project Air Force.

Sally DeBoer is an Associate Editor at CIMSEC.