By Anja Menzel

On July 2, 2020 at around 4:20 a.m., three vessels attacked the Sendje Berge, a floating production support vessel off the coast of Nigeria. While there were no physical injuries, the perpetrators took nine personnel hostage. The kidnapping is the latest incident in a series of attacks in the Gulf of Guinea, which has become the most piracy-infested region in the world, closely followed by Southeast Asia. Worldwide, 162 actual and attempted piracy attacks were reported in 2019.1 As most incidents have taken place in territorial waters, the cross-border nature of maritime crimes matters for ocean governance. When operating, pirates are not restrained by national borders, and exploit states’ inconsistencies in maritime security capacities and capabilities. Therefore, the unabatedly high numbers of attacks underlines the need for littoral and user states to cooperate on counterpiracy.

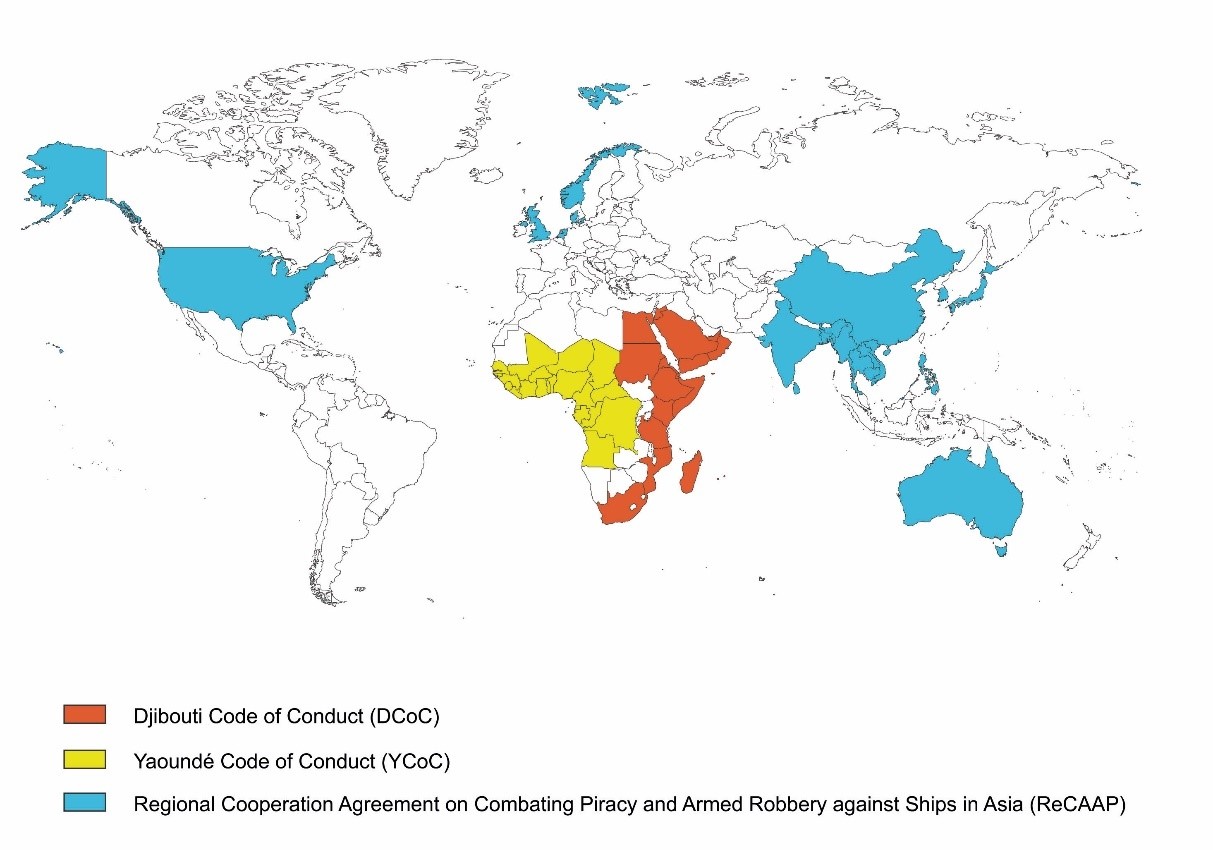

Three Regional Agreements to Govern Piracy

To govern maritime piracy through state cooperation, three agreements have been set up in different regions of the world. The members to these regional agreements agree to arrest, investigate, and prosecute pirates on the high seas, and to suppress armed robbery in their respective territorial waters. In Asia, the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (ReCAAP) was established in 2006. 14 regional states as well as six extra-regional states are currently contracting parties. In East Africa, the Djibouti Code of Conduct (DCoC) was agreed on in 2009. To date, 20 states from the Indian Ocean region have signed this agreement on the repression of piracy and armed robbery in the western Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Aden. In 2017, the DCoC’s piracy-only focus was expanded to include maritime crimes more generally when the so-called Jeddah Amendment was adopted by a subset of DCoC member states. Finally, the Yaoundé Code of Conduct (YCoC) to combat illicit maritime activities in West and Central Africa was signed in 2013 by 25 regional states.

As these agreements were successively established, policymakers were able to utilize insights from already developed setups elsewhere, a learning process that was actively sponsored by the International Maritime Organization. As a result, the agreements’ institutional structures are strikingly similar.2 This is most obvious in the agreements’ information-sharing structures. All agreements have Information Sharing Centers (ISCs) which collect data on maritime crimes and provide infrastructure for information exchange. The regional agreements also have a system of national focal points designated by each member state, which manage piracy and armed robbery incidents within the respective state’s territorial waters, report incidents to the ISCs, and coordinate surveillance activities with neighboring states.

Information Sharing and Capacity Building

These regional agreements have been rightfully praised as a milestone in ocean governance, as they are a strong symbol of the commitment of member states to combat piracy and other maritime crimes. The collection and dissemination of data on maritime crimes is one of the most important practical tasks carried out by the regional agreements, because to efficiently coordinate cooperation between maritime security actors it is crucial to have available all relevant information on the threat at hand. Furthermore, by creating reliability, regular information sharing has the potential to strengthen trust and confidence among key actors.3

Capacity building carried out through the framework of the regional agreements is equally important. To varying degrees, the agreements’ frameworks offer exercises, workshops, and trainings to accumulate expertise on and foster cooperation between national agencies and the shipping industry, and also provide technical assistance to member states. In fact, the regions cooperate in their capacity building efforts on a regular basis. Due to their similar institutional structures, ReCAAP and DCoC members held several joint workshops where best practices were shared.

The Limits of Cooperation

While the setup of the regional agreements is certainly a milestone in counterpiracy governance, the different regions are faced with a variety of challenges concerning cooperation in general and the implementation of the agreements’ provisions in particular.

Concerns over Territorial Sovereignty

Citing concerns over their territorial sovereignty, two of the states most affected by piracy in Southeast Asia, Indonesia and Malaysia, refuse to accede to ReCAAP. Although state cooperation in Asia is generally characterized by major sovereignty sensitivities, their reluctance is reinforced by ReCAAP’s open membership policy. While DCoC and YCoC have limited their membership to regional littorals, every interested state can join ReCAAP, which further fuels Indonesia’s and Malaysia’s concerns about foreign involvement in their territorial waters.4 However, the actual impact of the non-membership of key states in Asia remains unclear. Despite their official disapproval, both Indonesia and Malaysia cooperate with ReCAAP on a low-key level, participating in meetings and sharing select information. Nevertheless, an accession would certainly underline the two states’ willingness to commit to multilateral counter-piracy efforts given their strategic position in the Strait of Malacca and the Sulu and Celebes Seas.

Institutional Fragmentation

National sensitivities also led to a fragmented institutional landscape, both regionally as well as internationally. The DCoC operates three regional ISCs in Kenya, Tanzania, and Yemen. The YCoC architecture is even more fragmented, with regional maritime security centers for West as well as Central Africa in Congo and Ivory Coast, an interregional coordination center in Cameroon, and five coordination centers at the zonal level. Due to this fractional structure, information flows may be less efficient, and the ability to swiftly respond to undesirable events on the ocean could be hindered.5 While ReCAAP only operates one ISC, several other data-collecting bodies exist in Asia, such as the International Maritime Bureau’s Piracy Reporting Center and the Information Fusion Centre hosted by the Singaporean Navy. To complicate matters further, not all ISCs, particularly those in Southeast Asia, report data in a consistent way.6 Overall, the institutional plethora of information-sharing mechanisms underlines the importance of coordination between the different agencies. To this end, the regions’ potential to learn from each other’s experiences is not being fully realized yet.

Lack of National Capacities

To implement the regional agreements’ provisions on site, the capacities of member states are essential. However, member states’ means to counter maritime crimes in their territorial waters differ significantly. Some states, particularly in Asia, have comparably well-equipped navies, coast guards, and law enforcement agencies. In contrast, other states often lack those capacities, which is particularly apparent in Somalia and Yemen, which are both stricken by the devastating consequences of ongoing civil wars. Although the agreements offer capacity building measures, the mechanisms do not directly account for the resources of member states or their lack thereof.

Gaps in Scope

Although the regional agreements geographically cover the greater portion of world regions currently affected by piracy, there are still blind spots. Whole continents have not set up comparable cooperation mechanisms yet, such as Oceania and the Americas, where local piracy hotspots like the Caribbean and the Venezuelan coast would call for concerted governance efforts. This becomes more salient when not only piracy, but also maritime crimes more generally are in focus, since crimes such as illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing are pressing in every corner of the world

Additionally, the regional agreements are rather narrow in their operational scope. This is particularly obvious in Southeast Asia, where ReCAAP has thus far only institutionalized cooperation on piracy and armed robbery. As policymakers increasingly realize that these crimes are only one of many pressing issues in the maritime domain, the agreements may go one step further. Already in Africa, with YCoC as well as the DCoC’s Jeddah Amendment, the signatory states agreed to also cooperate on transnational organized crime in the maritime domain, maritime terrorism, IUU fishing, as well as other illegal activities at sea. By calling on its member states to develop national strategies for sustainable blue economic growth, the Jeddah Amendment, although very tentatively, even ties maritime security to the greater blue economy.

Looking Ahead

Threats to maritime security cannot be understood in isolation, as they are deeply interrelated. Going forward, maritime security governance will therefore need a more integrated understanding of the hazards posed by maritime crimes as well as the potential of coordinated efforts to combat these crimes.7 Specifically, it is necessary to strengthen maritime domain awareness by emphasizing potential synergies between combatting maritime crimes with the blue economy and the safety of the marine environment. This integrative understanding of developments and threats at sea is a prerequisite for coordination and cooperation between the diverse maritime security agencies and actors in this field.8 In that sense, the establishment of these regional counter-piracy agreements, their process of learning from each other and the gradual broadening of their scope, marks an important first step into realizing the full potential of an integrated approach toward maritime security governance.

Anja Menzel is a postdoctoral researcher at the FernUniversität in Hagen, Germany. She received her PhD in International Relations from Greifswald University, where she studied state cooperation on counterpiracy. Her current research interests include ocean governance, the construction of maritime spaces, and the link between the blue economy and development funding.

References

1. ICC IMB 2019. Report. Piracy and armed robbery against ships [1 January-31 December 2019]. London.

2. Menzel A. 2018. Institutional adoption and maritime crime governance: the Djibouti Code of Conduct. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 14(2), 152-169.

3. Bueger C. 2015. From dusk to dawn? Maritime domain awareness in Southeast Asia. Contemporary Southeast Asia 37(2), 157–182.

4. Lee T. and McGahan K. 2015. Norm subsidiarity and institutional cooperation: Explaining the Straits of Malacca anti-piracy regime. The Pacific Review 28(4), 529-552.

5. Ralby I. 2019. Learning from success: Advancing maritime security cooperation in Atlantic Africa. Center for International Maritime Security, [https://cimsec.org/learning-from-success-advancing-maritime-security-cooperation-in-atlantic-africa/41517].

6. Joubert, L. 2020. What we know about piracy. One Earth Future Foundation, [https://stableseas.org/publications/what-we-know-about-piracy].

7. Menzel A. and Otto L. 2020. Connecting the dots: Implications of the intertwined global challenges to maritime security. In: Otto, Lisa (ed): Global challenges in maritime security. An Introduction. Springer.

8. Bueger C. 2015. From dusk to dawn? Maritime domain awareness in Southeast Asia. Contemporary Southeast Asia 37(2), 157–182.

Featured Image: ReCAAP ISC Signs MOU with World Maritime University (February 7, 2018)