By Bill Bray

If you believe reading well or deep contemplation helps one be a better leader, consider how challenging it can be today to make a quiet place where one can be free from digital distraction. It requires quite a bit of discipline to train the mind to focus without interruption or read challenging texts. But reading them will, in turn, discipline the mind. It is a virtuous circle.

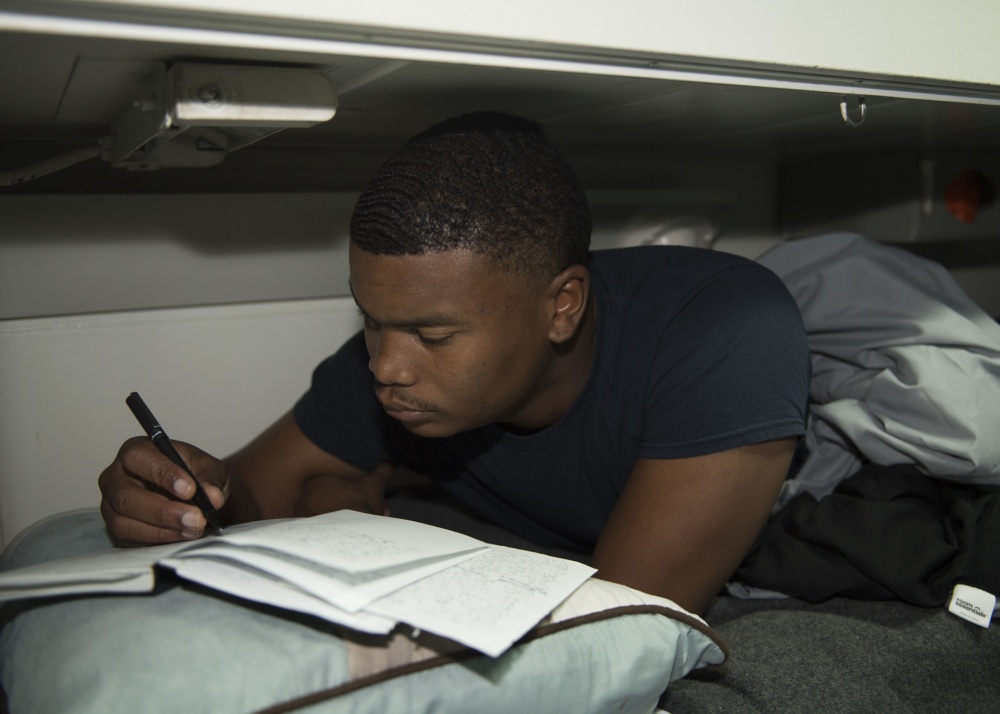

In 2005, I deployed to East Africa. It was my sixth deployment and I was excited about a new challenge in a part of the world I had never visited. I bunked in a small room with no television or internet connection. I brought with me a stack of books to read, knowing that for all their demands and challenges, deployments away from long commutes and domestic responsibilities provide more quiet time, even with longer work weeks.

Intensive deployment preparations during the preceding months allowed barely a spare moment to read, and after being on the ground for a few weeks and into a stable work rhythm I looked forward to diving in to some weighty but rewarding books. At first opportunity I expected to instantly relish again the joy of getting lost in a great book.

Instead, something quite disconcerting occurred. I could not concentrate long enough to continuously read much beyond a single page. I kept glancing up, expecting to be interrupted by something—an email alert, an instant message, a video call, a cell phone ringing. After half an hour of this, I slammed the book shut and marched up a dusty path to my office. I was agitated and tense, a telltale symptom of situational attention deficit disorder. I was also in a panic that my reading brain was lost forever.

That unsettling experience occurred before the introduction of the smart phone, a seminal event where opportunity to escape the temptress of digital distraction practically vanished. By the late 2000s, hyper-connection had arrived and has ever since waged unrestricted war against whatever is left of our undistracted quiet time. But to read and contemplate well one must fight back, so count me today as part of a growing backlash of folks disconnecting as often as possible each day.

I am no luddite. I prefer the comforts technology makes possible. People in the nineteenth century had plenty of quiet time, but I do not want to have to use an outhouse or fetch water from a well ten times a day. Nevertheless, new technologies often bring unintended consequences that need to be addressed. The detrimental effects of having one’s attention regularly distracted are by now well-established in a wide body of research. They include an impaired ability to perform a range of cognitive tasks and manage one’s emotions. Readers take note—do not try to read Macbeth with a smart phone within reach.

Deep in Distraction

In my view, the military has been slow to realize how important this is to ensure leaders nurture their minds. For more than two decades, the overarching theme when it came to the intersection of military leader development and information technology has been the more connected the better. It became a mantra that the breathtaking speed of innovation in information technology was changing warfare, and leaders needed to embrace, understand, and stay on pace with it. While it is hard on one level to argue against this imperative, it is now clear that it would be foolish not to heed science’s recent findings to determine how today’s hyper-connected digital environment is adversely affecting critical thinking skills prized in good military leaders.

The late Dr. Clifford Nass ran Stanford University’s Communication between Humans and Interactive Media (CHIME) Lab until his untimely death in 2013. For several years he stood at the forefront of research into the effects of multi-tasking through digital media on human cognitive and emotional development and performance. By the late 2000s CHIME and others were publishing peer-reviewed research detailing these effects, and warning that the proliferation of portable digital technology such as smart phones will only exacerbate the problem. Shortly before he died, Nass gave a wide-ranging interview to National Public Radio on what the body of research was revealing. The following excerpt captures the essence of the findings:

The research is almost unanimous, which is very rare in social science, and it says that people who chronically multitask show an enormous range of deficits. They’re basically terrible at all sorts of cognitive tasks . . . we have scales that allow us to divide up people into people who multitask all the time and people who rarely do, and the differences are remarkable. People who multitask all the time can’t filter out irrelevancy. They can’t manage a working memory. They’re chronically distracted. They initiate much larger parts of their brain that are irrelevant to the task at hand. They’re even terrible at multitasking. When we ask them to multitask, they’re actually worse at it. So, they’re pretty much mental wrecks.1

It goes without saying that military officers and leaders need their cognitive game at a level where they can, at a minimum, “filter out irrelevancy” and avoid being “mental wrecks.”

Since Nass’s 2013 interview, new studies have only reinforced how serious this problem is. Jean M. Twenge, a psychology professor at San Diego State, recently published research on how smart phones are impairing the mental and emotional development of teenagers. She documents this in her book iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy–and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood. This generation, first born in the mid-1990s, is just now joining the military. Boot camp and officer training are receiving young minds less able to focus after years of bombardment in a saturated digital media multi-tasking environment. Yet the military will not begin to address this problem until it stops sending its own signal that being digitally connected all the time is the right thing to do professionally. Always being “plugged in” with the latest tech and the media multitasking it persistently demands has for too long been championed as a vital tool of modern leadership, not something to be cautious about. It is time the military services take seriously the implications of cognitive science research.

The human brain is extremely elastic. While subjecting one’s mind to an excessive amount of distraction leads to a range of cognitive deficits, as Nass notes, freeing it from distraction as much as possible to permit time where one can fully focus on a single prolonged task, such as deep reading, improves the power of concentration. It should be noted that contemplation is not meditation, although that surely has health benefits as well. Contemplation is enjoyable but it is also a form of work, and doing it regularly is necessary to think well and keep sharp one’s ability to concentrate, whether to work through difficult conceptual issues or stay focused in otherwise chaotic environments.

The benefits of contemplation are also not something modern science discovered in the digital age. It would be more correct to say that through recent research, science rediscovered them through a far more intricate and evidentiary-based understanding of how the human mind works and what helps it work well. The ancient Greeks put great stock in the nurturing value of contemplation, and no less than Aristotle himself seemed to struggle with how best to balance the active and contemplative life. In book 10, sections 7 and 8 of Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle discourses on the human activity of the mind (theoria), commonly translated as contemplation. For Aristotle, the activity of study, or contemplation, is not something one does just to become learned. Instead, it is an activity that accords with virtuous character. Contemplation is an end in itself, a way to share in the divine, and not a task done solely to achieve some practical benefit. Nor does one need to engage regularly in contemplation to be a good citizen—that is quite achievable by developing what Aristotle termed ‘practical wisdom’ (phronesis). While Aristotle could not have envisioned digital technology and its pernicious influence on our ability to nurture our minds through contemplation, he did believe a life of action or activity that does not also include sufficient time for contemplation is not a life well-lived.2

Contemplation both requires and enhances a quiet, undistracted mind. And by engaging in it regularly, one also trains the mind to think beyond the concerns of day-to-day leadership and effectively engage with larger questions worthy of deeper thought—such as those of organizational change and strategy. We all know leaders who, in today’s parlance, are known as ‘big thinkers’ or ‘strategic thinkers.’ In referring to them in this way, we do not mean to imply only that they are very intelligent, which they surely are. The description more precisely captures an intellectual quality that must be consciously cultivated in the course of a career through regular study, undistracted focus, and deep contemplation. They read well.

At the risk of sounding like a crank complaining about young people today, one has to wonder if a smart-phone generation that feels obligated to be constantly connected and reachable at every waking moment is handicapping itself in cultivating the habits necessary to develop this quality. A professional culture that exalts as a desired leadership attribute the ability to function well in the frenetic cacophony of a media multi-tasking environment is undermining a much more essential requirement—that young leaders develop the important habits of mind necessary of senior leadership and strategic thinking.

Strike the Right Balance

Promising signs are emerging of a growing awareness to the digital age’s malign impact on cognitive health. The aforementioned research is spawning mainstream literature that serves as a public health warning and a guide on how to navigate today’s digital media-saturated environment so one can enjoy its benefits and innovations without exposing oneself to its dangers. There is a middle way that does not require the lifestyle of a hermit.

For example, in his 2017 book The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter, David Sax argues that the promised digital utopia has turned out to be a mirage. He points to a host of studies, surveys, and statistics to support this claim, but also is careful to prescribe a balance when incorporating digital media into one’s daily life, as opposed to abstinence. In addition, in 2018 Raymond Kethledge and Michael Erwin published Lead Yourself First: Inspiring Leadership Through Solitude, which includes examples of leaders who benefited greatly by committing regularly to silent time alone and free from distraction.

To read well, the leader must find this careful balance. Senior military leaders that came of age before the digital revolution are now retiring, but for the ones still in places of influence, or for any leader that senses there might be a problem, resist the temptation of connectedness and ensure those immersed in an ever-distracting daily milieu of digital stimuli can unplug regularly to nourish a well-focused mind. Leaders at all levels need to maintain sharp, focused minds, and the organization relying on their service owes them an environment where the mind can best flourish. I suspect those committed to reading well will need the least convincing.

Bill Bray is a retired Navy captain and currently the Deputy Editor-in-Chief of the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings.

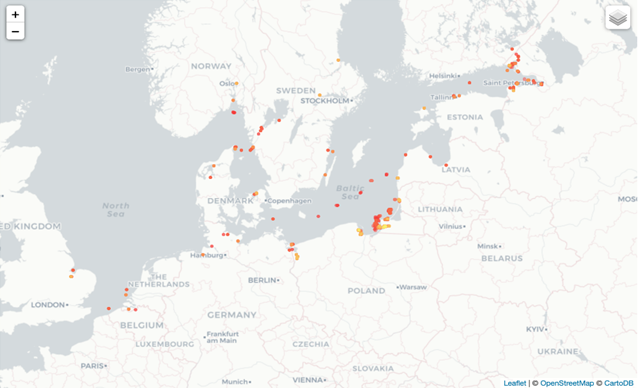

Featured Image: PENSACOLA, Fla. (Aug. 25, 2012) Hundreds of staff and students at the Center for Information Dominance Unit Corry Station muster early Saturday morning in preparation for Tropical Storm Isaac. (U.S. Navy Photo by Gary Nichols/Released)