Read Part One on the Battle of Locust Point. Read Part Two on the Nanxun Jiao Crisis.

By David Strachan

TOP SECRET/NOFORN

The following classified interview is being conducted per the joint NHHC/USNI Oral History Project on Autonomous Warfare.

Admiral Jeremy B. Lacy, USN (Ret.)

December 3, 2033

Annapolis, Maryland

Interviewer: Lt. Cmdr. Hailey J. Dowd, USN

Good morning.

We are joined again today by Admiral Jeremy B. Lacy, widely considered the father of autonomous undersea conflict, or what has come to be known as micronaval warfare. Admiral Lacy spearheaded the Atom-class microsubmarine program, eventually going on to establish Strikepod Group 1 (COMPODGRU 1), and serving as Commander, Strikepod Forces, Atlantic (COMPODLANT), as well as Commander, Strikepod Command (SPODCOM). He is currently the Corbin A. McNeill Endowed Chair in Naval Engineering at the U.S. Naval Academy.

This is the third installment of a planned eight-part classified oral history focusing on Admiral Lacy’s distinguished naval career, and his profound impact on modern naval warfare. In Part II, we learned of the aftermath of the Battle of Locust Point, and how continued Russian micronaval advances, most notably the nuclear-armed Poseidon UUV, led to the development of AUDEN, the Atlantic Undersea Defense Network. We also learned of CYAN, a “walk-in” CIA agent who revealed Chinese penetration of the AUDEN program, and the resulting emplacement of numerous AUDEN-like Shāyú microsubmarine turrets throughout the South China Sea. One of these turrets, at Gaven Reefs, known to the Chinese as Nanxun Jiao, was directly involved in engaging the USS Decatur, and was subsequently the target of an undersea strike which resulted in the deaths of four Chinese nationals, including CYAN himself.

The Nanxun Jiao Crisis was a wakeup call for the United States. With Chinese militarization of the South China Sea expanding to the seabed, a new sense of urgency now permeated the U.S. national security establishment. Pressure was mounting to counter China’s increasing belligerence and expansionist agenda, but doing so risked igniting a regional conflict, or a confrontation between nuclear-armed adversaries.

We joined Admiral Lacy again at his home in Annapolis, Maryland.

Let’s begin with the immediate aftermath of Operation Roundhouse. How impacted was Strikepod Command by the events of that day?

It was devastating. Unimaginable, really. That we’d had a hand, however unwittingly, in the murder of four people, and watched it unfold in real time right before our eyes – you can’t prepare for something like that. They brought in counselors from Langley [Air Force Base] – chaplains, experienced drone pilots who’d been through this kind of thing. But for a lot of talented people it just wasn’t enough, and they had to call it a day.

For those who remained the trauma eventually gave way to anger, and then determination. But the feeling of betrayal, of vulnerability, was difficult to overcome. All we could do was move on as best we could.

The CYAN investigation would eventually yield a single spy – Charles Alan Ordway , a FathomWorks contractor motivated apparently by personal financial gain. But you weren’t convinced that was the end of it.

Ordway worked on AUDEN, but he didn’t have code word clearance, so while it was true that he had passed sensitive information to the Chinese, there was really no way for him to have known of Roundhouse or CYAN. From a counterintelligence perspective, he was low hanging fruit, and I believed – and continue to believe to this day – that there was someone else.

The intelligence provided by CYAN led to the discovery of several operational Shāyú installations in addition to Nanxun Jiao. What was the reaction in policy circles?

Alarm bells were going off throughout Washington, and we were under extraordinary pressure not only to process the raw intelligence, but to understand the broader implications of China’s growing micronaval capability, particularly as it applied to gray zone operations. It was quite clear now that strategic ambiguity was no longer appropriate, and if policymakers were waiting for a reason to act, it seemed Nanxun Jiao was it.

And yet, apparently it still wasn’t.

No. The president felt that while the Shāyú emplacements represented a concerning development in the South China Sea, there was little difference between seabed microsubmarine turrets and onshore ASCM batteries. Keep in mind, it was also an election year, a time when politicians generally avoid starting wars. And there was additional concern that any escalation in the South China Sea would have an adverse impact on the restarted negotiations with North Korea.

So we were in a holding pattern, a period of strategic paralysis, really. No additional strikes were authorized, or even under consideration. We’d sent a message with Roundhouse, and the Chinese answer was continued harassment and militarization. They were dug in and practically daring us to escalate. And with neither side willing or able to consider a diplomatic solution, the tension was left to fester.

Let’s come back to that, if we could, and talk a bit about developments at FathomWorks. The Atom-class was proving to be a phenomenally successful platform, and you were now being called upon to replicate that success in another domain.

Once the dust had settled I got a call from Chandra [Reddy, the ONR Atom-class liaison] who wanted to chat about Falken [the Atom-class artificial intelligence], and specifically whether I thought it could be adapted to an unmanned surface vehicle. We got to talking, and he says you know what, Jay, there’s someone you should meet. Next day, I’m off to Olney [Maryland] with Max [Keller, Director of AI for the Atom-class] to meet with Talia Nassi.

Was that name familiar to you?

She was three years behind me at the Academy, and our paths had crossed a couple times over the years at conferences and training sessions. She was pretty outspoken and wasn’t afraid of ruffling a few feathers, especially when it came to unmanned systems and what was then being called DMO, or distributed maritime operations. Like everyone else, though, I knew her as the maverick commander who’d taken early retirement to start Nassi Marine.

But you had no idea she was behind the Esquire-class?

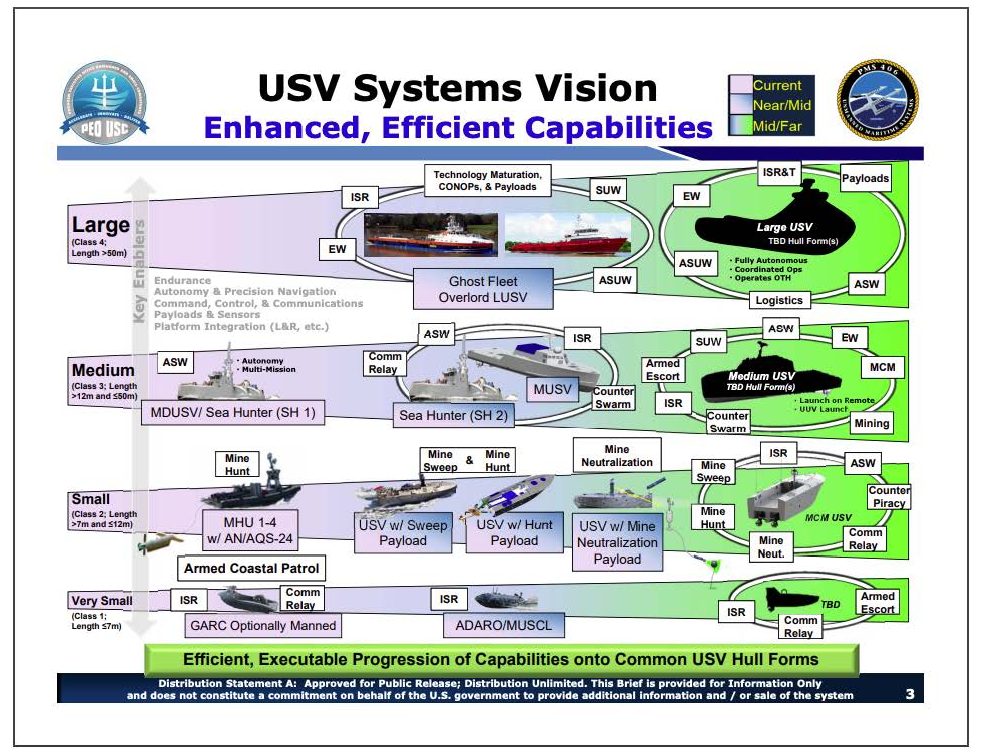

I had no idea that such a program even existed. It was highly compartmentalized, as these things tend to be. Very need to know. But there’d been rumors that something was under development, that [DARPA/ONR] Sea Hunter was really a prototype for a deep black program, something highly advanced and combat-oriented.

And so you arrive at Nassi Marine…

And Talia greets us in the lobby. Then it’s off to the conference room for small talk, sandwiches, and coffee. Then onto Falken and its potential for USVs. And then after about fifteen minutes Talia politely asks Max if he wouldn’t mind waiting outside. He leaves, and she reaches down, plucks a folder from her briefcase and slides it across the table. I open it up, and I’m looking down at a something straight out of Star Trek.

The Esquire-class?

It was honestly more spaceship than warship, at least on paper. Trimaran hull, nacelle-like outriggers, angular, stealth features. And for the next half hour or so, Talia briefs me on this revolutionary unmanned surface combatant, and I’m thinking, wow, this is some really impressive design work, not really imagining that it’s moved beyond the drawing board.

Did you wonder why you were being brought into the fold?

As far as I knew, I was there to talk about Falken, so it did strike me as odd that I’d be briefed on a deep black surface platform. But it wasn’t long before I understood why. One of the main features of the Esquire was its integrated microsubmarine bay. Talia had originally envisioned something that could accommodate a range of micro UUVs, but ultimately decided to focus on the Atom given its established AI and the seamless integration it offered.

Nassi Marine headquarters is sometimes referred to as “Lake Talia” for its enormous wave pool and micronaval testing facility. Did it live up to its name?

Absolutely!

When Talia finishes her briefing, I follow her down the hall and through a set of doors, and suddenly I’m staring at the largest indoor pool I’ve ever seen. It’s basically her own private Carderock, but nearly four times the size and twice as deep. When she founded Nassi Marine, Talia wanted somewhere she could put classified systems through their paces in a controlled, secure environment that was free from prying eyes. Dahlgren [Maryland] and Bayview [Idaho] were far too visible for her, so she acquired some surplus government land in rural Maryland and nestled a cutting edge R&D facility between a country club and an alpaca farm.

Was there a working prototype of the Esquire?

Talia walks me over to the dry dock, and there it is.

What was your impression?

I was struck by how small it was. At only fifty feet long, it was less than half the length of Sea Hunter. But it looked fierce, and according to Talia, packed a mean punch. Fifty caliber deck gun, VLS for shooting nanomissiles and Foxhawks, a newly developed swarming drone. It also featured a hangar and landing pad for quadrotor drones, as well as two directed energy turrets and countermeasure launchers. And of course, the integrated well deck-like feature for the launch and recovery of microsubmarines. And these were just the kinetics. It also packed a range of advanced sensors and non-kinetic effectors as well.

So, between the engineering and AI integration, you had your work cut out.

Indeed we did. Talia put me on the spot for an ETA, and after giving it some thought, I estimated six to nine months for the full deal. That’s when she hits me with the punch line: “You’ve got three.”

Three months?

Three! I was like look, we might be magicians at FathomWorks, but we’re not miracle workers. And anyway what’s the hurry? Talia looks me right in the eye and says, “Because in about 18 months it’s headed to the South China Sea.”

Did that come as a shock?

The timetable was certainly a shock, but it was also the first I’d heard that any plans for escalation had moved beyond the gaming table. The handwriting had been on the wall for years, of course, so I wasn’t surprised, and honestly it came as a relief knowing that a tangible response was finally in the offing.

So you embark on the Atom integration, and at the same time you’re overseeing Eminent Shadow . . .

Which has now been greatly expanded in the wake of Nanxun Jiao. At its peak I think there were no less than forty Strikepods – about two hundred fifty Atoms – dotting the Spratlys and Paracels, providing FONOP escort and monitoring PLAN and militia activities both on and below the surface.

And the Shāyú was proving itself to be an ideal tool for the gray zone.

Indeed. After Nanxun Jiao, the Chinese were utterly emboldened and were becoming ever more ballsy. Nearly every FONOP was met with Shāyú harassment, and even though we’d stepped up Atom production and significantly increased our operational footprint, it was challenging to keep up. And PLAN engineers were becoming ever more creative.

How so?

They’d been working on a micro towed array for the Shāyú, similar to what we’d been developing for the Block II Atom. From what we could tell, they weren’t having much success, but they did find that it could be effective for gray zone effects. Shāyús would make runs at our DDGs with arrays extended, and once in a while penetrate the Strikepod perimeter and foul the screws pretty good. Even if publically the Chinese didn’t take credit, there was significant propaganda value in disabled U.S. warships.

Were you also monitoring for new indications of seabed construction?

Our main concern was the northeastern Spratlys and southern Paracels near the shipping lanes. With a foothold in either of those locations, the Chinese would have near complete maritime domain awareness over the South China Sea. So our mission was to closely monitor those areas, and report back anything anomalous. It wasn’t long before we found something.

The emplacements at Bombay Reef and Scarborough Shoal?

We’d been monitoring inbound surface traffic when satellites spotted some unusual cargo being loaded onto a couple fishing trawlers up in Sanya. We vectored Strikepods as they departed, and trailed them to Bombay and Scarborough where we snapped some surface imagery of divers and equipment being lowered over the side. We monitored for about five days, keeping our distance, and picking up all manner of construction noise. We’re itching to take a look, but wait patiently for crew changes and quickly order the imagery. The Strikepods are in and out in under five minutes, and two Relay burst transmissions later we’re looking at the beginnings of Shāyú turrets at both locations.

What was your analysis?

It indicated that the Chinese were planning for future confrontations in the region – gray zone or conventional, most likely due to their planned militarization of Bombay and Scarborough.

The implications were grave. Vietnam had a history of taking on great powers and winning, and had pushed back hard on China in the past. And while Duterte had been cozying up to Beijing and drifting away from the U.S., Scarborough Shoal would be a red line. A provocation like this could be just the excuse Hanoi and Manila needed to act.

Did the United States share the intelligence?

Not initially, no. First and foremost we needed to safeguard sources and methods, and sharing anything would reveal our micronaval capabilities which were still highly classified and largely unknown. The Shāyú was also still a mystery, and divulging what we knew to Hanoi or Manila would risk exposure to Beijing. And we couldn’t be sure that they wouldn’t act unilaterally, igniting a conflict that could draw us into a war with China.

You were obviously busy at SPODCOM overseeing Eminent Shadow, but FathomWorks was also working intensively now with Nassi Marine.

Once we discovered Bombay and Scarborough, the sense of urgency was high, and we were working around the clock to get the Esquire combat ready. We ran through countless simulated missions in the Lake, and eventually at sea off North Carolina. Talia handed it off for production on time and under budget, and we joined the operational planning underway at Seventh Fleet.

Eminent Shadow was about to become Eminent Shield?

Yes. Of course planning for a South China Sea incursion had been underway for several years, and it was only after Locust Point that I’d been asked to join, to integrate micronaval elements into the wargaming framework.

But during those games, there was no mention of the Esquire?

Not initially, no. All we were told was that, in addition to being deployed from Virginias and surface ships, Strikepods could also be launched and recovered from a hypothetical USV with fairly abstract capabilities. But once the Esquire moved beyond the design phase, and there was a working prototype, it was folded into the games going forward.

And those games formed the basis for Eminent Shield?

Eventually they did, yes, but initially we were running scenario after scenario of high-end warfighting. There were some smaller skirmishes and limited conflicts where we intervened on behalf of regional states, but in general the primary objective was always either stopping or rolling back Chinese expansion, with the Esquires called upon as a force multiplier to augment ISR and EW, act as decoys, deploy Strikepods for ASW and counter-microsubmarine ops, and take out small aerial threats. Plausible to be sure, but at some point it occurred to me that the Esquire might enable us to project power in a less conventional, but no less effective manner. To essentially meet the Chinese where they were.

So we gamed some scenarios where the U.S. assumed a greater presence in the South China Sea using unmanned systems. Something beyond FONOPS and undersea reconnaissance. Something visible and formidable enough to send a strong signal to Beijing without provoking a shooting war. A kind of gray zone gunboat diplomacy, if you will, pushing things to the edge while gambling that the Chinese wouldn’t resort to a kinetic response.

Turnabout is fair play.

That it is.

How was it received?

Well, people appreciated that it was bold and imaginative, I suppose, but ultimately felt it was fraught with uncertainty, that it would only serve to antagonize the Chinese, and quickly escalate to high-end conflict anyway.

So it went to the back burner?

Yes, but I continued to refine it, along with input from Talia, who eventually came on board as strategic advisor, as well as some folks at the Pentagon and Intelligence. Once the discoveries at Bombay and Scarborough happened, though, the administration was looking for options . . .

And you got the call-up.

Yes, ma’am.

What was the plan?

The overarching objective of Eminent Shield was to signal that the United States would no longer sit idly by as the South China Sea was transformed into a Chinese lake. And we would do this by establishing a permanent distributed maritime presence in the region using a network of unmanned surface combatants.

The plan itself involved four sorties of LSDs out of Sasebo to essentially seed the region with Esquires. At fifty feet long, with a beam of seventeen, we determined that a dozen would fit into the well deck of a Whidbey Island. After some practice with the Carter Hall and Oak Hill down at [Joint Expeditionary Base] Little Creek, we airlifted forty-eight to Sasebo, where they were loaded onto the Ashland, Germantown, Rushmore and Comstock. Separated by about thirty-six hours, they sailed on a benign southwesterly heading between the Spratlys and the Paracels, escorted by an SSN and two or three Strikepods to monitor for PLAN submarines and Shāyús. At a predetermined waypoint, and under cover of darkness, the Esquires would deploy, then sail to their preprogrammed op zone – two squadrons to the Paracels, two to the Spratlys, and one to Scarborough Shoal – and await further orders.

Was there concern that the Chinese would view such a rapid deployment as some kind of invasion? A prelude to war?

We considered a more incremental approach, something less sudden. But we needed to act quickly, to avoid any kind of coordinated PLAN response – a blockade or other high profile encounter that could escalate. A rapid deployment would also underscore that the United States Navy had acted at a time and place of our choosing, and that we could operate in the South China Sea with impunity. At the end of the day, the Esquires were really nothing more than lightly armed ISR nodes, and were far less ominous than a surge of CVNs or DDGs.

Did it proceed as planned?

For the most part, yes. There were some technical hiccups, with three Esquires ultimately refusing to cooperate, so the final package was forty-five – nine vessels per squadron. The pilots and squadron commanders were based out of SPODCOM in Norfolk, but the Esquires were fully integrated into the regional tactical grid, and, if necessary, could be readily controlled by manned assets operating in theater.

And you were able to avoid PLAN or PAFMM harassment?

By sortie number four we’d gotten their attention – probably alerted by a nearby submarine – and three CCG cutters were vectored onto the egressing LSDs. But the deployment went off without incident, and in a few days all four ships were safely back in Sasebo.

And then we waited.

How long was it before the PLAN became aware?

It was about thirty-six hours before we began to see some activity near Subi Reef. The Esquire is small, and has a very low cross section, so it was unlikely they’d been tagged by radar. More likely they’d been spotted by an alert fishing boat, or passing aircraft, or possibly the heat signatures of the LENRs lit up a satellite.

At around 0300 I wake up to an “urgent” from the watch that about a dozen fishing boats were converging on Subi. So here we go. By the time I get to the office they’ve got the live feed up, and I watch the maritime militia descending in real-time. We order the Equire to deploy a six-ship Strikepod to enhance our visual, and pretty soon we’ve got a wide angle on the whole scene – lots of little blue men with binoculars, clearly perplexed, but no indications of imminent hostilities. This goes on for nearly three hours, until we notice some activity on one of trawlers. They’re prepping a dinghy with some tow rope and a four-man boarding party.

They’re going to grab it?

Certainly looks that way. They lower the dinghy and make their way over, inching to within ten meters or so, and that’s when we hit them with the LRAD [Long Range Acoustic Device], blasting a warning in Chinese – do not approach, this is the sovereign property of the United States operating in international waters. Things along those lines.

They turn tail and beat it back to the ship, but they’re not giving up. Next thing we see guys tossing headphones down to the dinghy. Needless to say, we weren’t about to give them a second chance, so we quickly order the Strikepod recovered and hit the gas.

Did they pursue?

They tried. But the Esquire can do about forty knots, and by the time they knew what was happening, we already had about 500 yards on them, so they gave up fairly quickly.

I imagine it wasn’t much longer before the other Esquires were discovered?

Word spread quickly of that encounter, and no, it wasn’t long before Esquires were being engaged by militia at multiple locations. In some cases they would try to board, in others they would attempt to blockade or ram. But the Esquires were too maneuverable, and between Falken and the pilots, we managed to stay a step or two ahead.

Had you anticipated this?

We’d anticipated the initial confusion and fits of arbitrary aggression. We also anticipated the political backlash, of course.

Which did manifest itself.

Yes, but not entirely how we’d envisioned. We knew that Beijing would be furious that the United States had mounted such an aggressive op in their own backyard. But at the same time, would they really want to draw that much attention to it? Wouldn’t that be underscoring the U.S. Navy’s ability to operate anywhere, anytime?

And the PLAN’s inability to prevent it.

Sure enough, state television reports that a U.S. Navy unmanned surface vehicle – singular – had violated Chinese sovereignty and was engaged by PLAN forces. Video footage flashed from a PLAN destroyer to a rigid hull speeding toward an Esquire, to a couple of hovering [Harbin] Z-9s. The implication was that the Esquire had been captured or otherwise neutralized, yet all forty-five were fully functional and responding. It was a clever propaganda stroke, but by going public, the Chinese had opened a Pandora’s box.

Because now the Western media was all over it?

And with the Esquire out in the open, we’d have a lot of explaining to do. There would be questions about capabilities, deployment numbers …

To which the answer was?

That we don’t comment on ongoing operations, of course. But, through calculated leaks and relentless investigative reporting, the Chinese would quickly realize what they were dealing with, and what it signaled in terms of U.S. intentions and resolve.

And meanwhile Eminent Shield continued. With unmanned FONOPS?

To start with, yes. The Esquires initially had taken up position outside twelve miles, but we soon began moving them intermittently inside territorial limits to deploy and recover a drone. By this point militia boats were always shadowing, and would move quickly to harass the Esquires as best they could.

But then we upped the ante a bit. We’d use onboard EW effectors to spoof their GPS and AIS. We’d lure their destroyers to one location while a DDG ran a FONOP just over the horizon, unmolested. We’d form ASW dragnets using smaller squadrons of three or four Esquires with their towed arrays and Strikepods deployed, sonar banging away.

And, yeah, we also installed dead wire in the towed arrays of some of the Atoms, so we were able to return the favor and foul some screws of our own.

What about the Shāyús?

The Shāyús were the greatest source of trouble for the Esquire, and we’d anticipated this. We couldn’t be certain whether or how the Chinese might engage the Esquires on the surface or in the air, but we were absolutely certain that there would be attacks from below.

But with the Esquire’s waterjets there were no screws to foul. And a six-ship Strikepod was deployed as an escort at all times, and there were also Firesquids [anti-torpedo torpedoes] for additional defense. But even so, the Esquires were quite vulnerable, and the Shāyús quickly moved to exploit this.

In what way?

The Esquires were defending well, but the Shāyú’s tactics were evolving. Initially they would engage the Atoms ship-to-ship and attempt to defeat them before moving on to the objective. But soon they learned to avoid the Atoms altogether and engage in hit and run attacks from below, targeting the Esquire’s stern in an attempt to ram and disable the microsubmarine bay and propulsion. Living up to their namesake, I suppose. [Shāyú is Mandarin for shark.]

Did Falken adapt accordingly?

Falken quickly recognized the need to deploy its full complement of Atoms to defend against the volume of attacking Shāyús, and actually began to form smaller squadrons of two or three Esquires to offset the numerical disadvantage. Falken also ordered escorting Strikepods to assume a tighter, closer formation, one that emphasized protecting the Esquire’s belly and backside, and began using Firesquids as decoys to great effect, something we hadn’t even considered.

Atom attrition was high then?

For a time, yes, and resupply was challenging. The payload modules on nearby Virginias were filled to capacity, but that was only around forty or fifty units. At the rate we were losing them, we’d be critical in a matter of weeks.

So the Shāyús adapt, Falken counters, but the attacks continue until one day the Shāyús succeed in disabling an Esquire within twelve miles of Mischief Reef.

And now it’s a race to recover.

The [USS] Mustin [DDG 89] was about forty kilometers away, and was immediately ordered to the area. The PLAN had also been alerted, and vectored the destroyer Haikou, which was only five kilometers away. So Mustin puts a Seahawk up, but even at full throttle Haikou is still going to win that race.

Haikou arrives, and they immediately put a boarding party in the water. ETA on the Seahawk is two minutes, and the Mustin is still thirty minutes away at flank. We blast the LRAD, but they’re wearing headphones now, so we fire a warning from the 50 cal, and light off a small swarm of Foxhawks. This gets their attention, and manages to buy us the few minutes we need.

The Seahawk arrives, loaded with Hellfires, and five minutes later, Mustin appears on the horizon. Now we’ve got ourselves a standoff. The Chinese are making threats, and we’re making counter-threats. And then the militia shows up – fishing boats, CCG, wrapping cabbage to cut off Mustin and the Esquire. And so we’re eyeball to eyeball, now, fingers on the trigger.

An hour goes by. Two. Eight. “Stand by” is the order. Twelve hours. Darkness falls, and we keep vigil through the night. By now, the media has it, and talk of war is everywhere. A new day dawns on the South China Sea, and around 1930 Eastern, I’m summoned to the vault for a telepresence with the Sit Room.

To brief?

Not exactly.

First they asked me to confirm the conclusions of my earlier analysis, that the Shāyú emplacements were likely a gray zone prelude to a Chinese land grab at Bombay Reef and Scarborough Shoal.

Then they asked whether I believed the Chinese would willingly dismantle Bombay and Scarborough in return for withdrawal of the Esquires.

And did you?

The Chinese would want the Esquires gone ASAP for political reasons, but they also were well aware of their capabilities, and how they would dramatically augment U.S. firepower in the event of regional hostilities. It seemed to me that Beijing would be willing to forfeit those locations if it meant a reduced U.S. military presence, and also the ability to save face by appearing to expel the U.S. Navy from the South China Sea.

And then I offered a pretty candid, if unsolicited, opinion on the deal.

Which was?

That the Chinese would be getting much more than they were giving up. That dismantling the emplacements, while a short-term loss for the Chinese and a gain for us, would do little to deter future militarization. The U.S. would also be giving up significant strategic leverage, and potentially damaging our credibility in the process.

So you were against it?

You’re damn right I was. Call me a hawk, but we’d gone round after round with Beijing for over a decade, and then took one on the chin at Nanxun Jiao. We’d finally taken decisive action, and now we’re just going to let it slip away?

But ultimately it did.

Unfortunately, yes.

Around 2200 the Chinese suddenly back off, and Mustin is allowed to move in and recover the Esquire. The next day news breaks of emergency multilateral talks in Tallinn, Estonia involving the U.S., China, Vietnam, Brunei, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

There was great optimism leading up to Tallinn, that this could be the diplomatic breakthrough that would empower regional states to push back on Beijing knowing that the U.S. had their back. But ultimately it was not to be. The Chinese dismantled the Shāyú emplacements at Bombay and Scarborough, and in return the United States withdrew every last Esquire. Beijing also pledged to work toward “greater understanding” with its neighbors and other ambiguous words to that effect. The Tallinn Communiqué was hailed as a success by all, but for entirely different reasons. The U.S. and our allies believed this was a significant step toward regional stability by checking Chinese expansionism. The Chinese, meanwhile, declared victory in having expelled the United States from its backyard while strengthening its role as regional hegemon.

Were you disappointed with the outcome?

Disappointed? Perhaps. The Navy exists to ensure peace and protect U.S. interests through strength, and so when policy seems at odds with that mandate, yes, I guess it makes me bristle. But I wasn’t surprised. Tallinn wasn’t the first toothless resolution in the history of international diplomacy, and it certainly wouldn’t be the last.

And all I could think, sitting there in SPODCOM, watching the last of the Esquires being recovered under the watchful eye of PLAN warships, was that it wouldn’t be long before we’d be back there again.

Only next time, things might not end so cleanly.

[End Part III]

David R. Strachan is a naval analyst and writer living in Silver Spring, MD. His website, Strikepod Systems, explores the emergence of unmanned undersea warfare via real-time speculative fiction. Contact him at strikepod.systems@gmail.com.

Featured Image: “The Middle of Nowhere” by hunterkiller via DeviantArt