By LT Coleman Ward

Introduction

To better meet today’s force demands, [we must] explore alternate fleet designs, including kinetic and non-kinetic payloads and both manned and unmanned systems. This effort will include exploring new naval platforms and formations – again in a highly “informationalized” environment – to meet combatant commander needs.

– Admiral John Richardson in A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority

Today’s military operating environment is more complex than ever. While the principles of warfare have remained relatively unchanged throughout history, the development of advanced military capabilities and employment of unconventional styles of warfare increasingly challenge the way commanders are thinking about future conflict. Potential adversaries are further complicating the operating environment through various anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) mechanisms. While many countries are developing such capabilities, this article will focus primarily on the threat of the People’s Republic of China (PRC’s) maritime development. The PRC is rapidly improving its air, surface, and subsurface platform production as it continues its quest for exclusive control of untapped natural resources within the “nine-dash line” region.1 Additionally, the PRC is equipping these platforms with improved weapons that can reach further and cause more damage.2 As a result, the U.S. Navy will assume greater risk when operating in complex A2/AD environments such as the Western Pacific. To mitigate this risk, the U.S. Navy is developing innovative warfighting concepts that leverage technologies and assets available today. The incorporation of unmanned systems into maritime domain operations provides one example where the U.S. Navy is making significant progress. Another example is the inception of a new surface warfighting concept called Distributed Lethality.

In January 2015, Vice Admiral Thomas Rowden (Commander U.S. Naval Surface Forces) and other members of the surface warfare community’s higher leadership formally introduced the opening argument for how the Surface Navy plans to mitigate the A2/AD challenge in an article titled “Distributed Lethality.”3 In this inaugural piece, the authors argue, “Sea control is the necessary precondition for virtually everything else the Navy does, and its provision can no longer be assumed.”4 The “everything else” corresponds to promoting our national interests abroad, deterring aggression, and winning our nation’s wars.5 At its core, Distributed Lethality (DL) is about making a paradigm shift from a defensive mindset towards a more offensive one. To enable DL, the U.S. Navy will increase the destructive capability of its surface forces and employ them in a more distributed fashion across a given theater of operation.

DL shows promise in executing the initiatives provided in the Chief of Naval Operations’ Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority in the years to come.6 However, as the U.S. Navy continues to invest in promoting DL, there is a danger that improper fusion of this new operating construct with the foundational principles of war could lead to a suboptimal DL outcome.7 To optimize the combat potential inherent to DLin an A2/AD environment, the Navy must develop and apply the concept of “Autonomous Warfare.” Autonomous Warfare addresses both enabling decentralized, autonomous action at the tactical level through careful command and control (C2) selection at the operational level and further incorporating unmanned systems into the Navy’s maritime operating construct. A flexible C2 structure enabling autonomous action supported by squadrons of unmanned systems optimizes DL and ensures its forces will deliver the effects envisioned by this exciting new concept in the most challenging A2/AD environments. DL advocates put it best in saying that “we will have to become more comfortable with autonomous operations across vast distances.”8 This paper will first examine why DL is an appropriate strategy for countering A2/AD threats before developing the main argument for Autonomous Warfare. This paper concludes by examining how the combined effect of autonomous C2 and aggressive implementation of unmanned systems will achieve the desired results for Autonomous Warfare as it applies to DL, followed by a series of recommendations that will assist with implementing this new idea.

Why Distributed Lethality?

“Naval forces operate forward to shape the security environment, signal U.S. resolve, protect U.S. interests, and promote global prosperity by defending freedom of navigation in the maritime commons.”9 During war, one of the Navy’s principal functions is to gain and maintain sea control to facilitate air and ground operations ashore. An adversary’s ability to execute sea denial makes the endeavor of exercising sea control increasingly challenging. A key driver behind DL is countering advances in A2/AD capability, a specific sea denial mechanism, which inhibits the Navy’s capacity to operate in a specific maritime area.10

A2/AD is a two-part apparatus. Anti-access attempts to preclude the entrance of naval forces into a particular theater of operation. For example, the threat and/or use of anti-ship cruise and ballistic missiles can hold surface vessels at risk from extended ranges.11 The PRC’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is one of the many navies that deploy various anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), out of a global arsenal of over 100 varieties that can reach nearly 185 miles.12 Of its anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), the PRC’s renowned “carrier killer” (DF-21D), with a range of 1000 plus miles, is generating cause for concern from an anti-access perspective.13 Additionally, submarines operating undetected throughout a given area of operation (AO) can deter surface forces from entering that area without significant anti-submarine warfare (ASW) capability. On the other hand, area denial seeks to prevent an adversary’s ability to maneuver unimpeded once a vessel has gained access to an area.14 While employment of the aforementioned missiles poses a threat in a combined A2/AD capacity, the PRC’s shipbuilding trend is triggering additional alarms from an area denial perspective. A recent workshop facilitated by the Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI) highlighted that the PRC has surged its shipbuilding efforts more than ten times over from 2002 to 2012 and will likely become the “second largest Navy in the world by 2020” if production continues at this pace.15 Indeed, the PRC has generated and continues to produce significant capacity to practice A2/AD and maintains a formidable shipbuilding capability. These observations are just a few amongst a host of many that spark interest in shifting American surface forces toward a DL-focused mindset.

One might ask, “How does DL help mitigate these A2/AD concerns?” Ever since carrier operations proved their might in the Pacific theater during World War II, U.S. naval surface combatants have principally acted in defense of the aircraft carrier. Essentially, the surface force relies predominantly on the firepower wrought by the carrier air wing, while other surface ships remain relatively concentrated around the carrier and defend it against enemy threats from the air, surface, and sub-surface. A well-developed A2/AD operational concept married with a diverse and sophisticated array of systems is advantageous against this model for two reasons: that adversary could hold a limited number of high value units (the carriers) at risk with only a small number of ASBMs, while the imposing navy could only employ a fraction of its offensive capability due to a necessary focus on defensive measures. DL addresses both concerns by deploying progressively lethal “hunter-killer” surface action groups (SAGs – more recently referred to as Adaptive Force Packages) in a distributed fashion across an area of operation (AO). By doing so, the DL navy will provide a more challenging targeting problem while offering the commander additional offensive options.16 DL shifts the focus of the Navy’s offensive arsenal from its limited number of aircraft carriers to the surface navy as a whole.

Potential Shortcomings

DL addresses the challenges of operating in an A2/AD environment by dispersing offensively focused surface combatants across the theater. To be effective, however, the operational commander must assign an appropriate C2 structure for DL forces. The DL operating concept could rapidly dissolve through the development and implementation of complex command and control structures. Furthermore, inadequate use of unmanned systems presents an additional potential shortcoming to the effective application of DL. While the consequences of these shortcomings would not be cause for instantaneous failure, they could create adverse second and third order effects and result in deterioration of the DL concept.

Command and Control

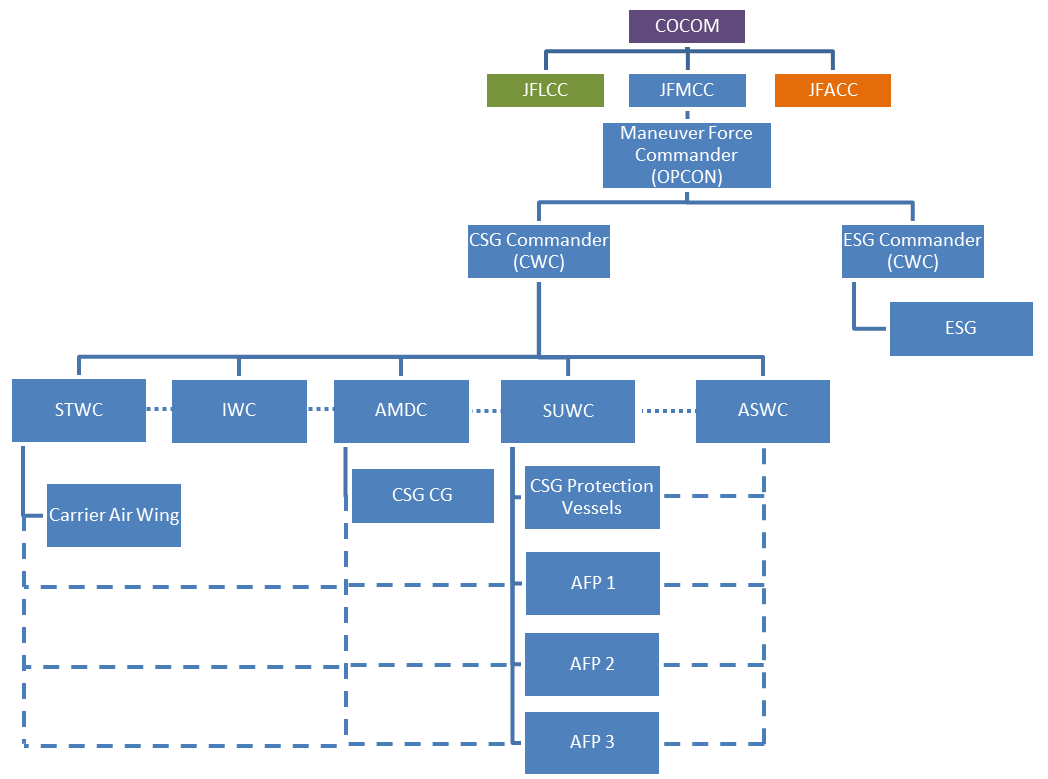

Effective C2 is the cornerstone of the successful execution of any military operation. Service doctrine aids in establishing the proper balance between centralized and decentralized C2. The Naval Doctrine Publication 1 for Naval Warfare defines C2 as “the exercise of authority and direction by a properly designated commander over assigned and attached forces in the accomplishment of the mission.”17 Further, the Joint Publication for C2 and Joint Maritime Operations highlights that a clear understanding of commander’s intent should enable decentralized execution under the auspices of centralized planning.18 Instituting the appropriate C2 structure based on the mission at hand and composition of employed forces helps achieve maximum combat utility while minimizing the need to communicate. This is particularly important when the operational commander has cognizance over a large number of forces and/or when the enemy has degraded or denied the ability to communicate. As the absence of a notional C2 architecture for Adaptive Force Packages (AFPs) at the operational level represents a significant gap in the DL concept, this paper will provide a traditional Composite Warfare Commander (CWC) approach to commanding and controlling AFPs, followed by a potential solution through the lens of Autonomous Warfare.19 The intent is to show that thinking about AFPs as autonomous units will uncover innovative ways to assign C2 functions and responsibilities amongst DL forces.

Unmanned Systems

The proper employment of unmanned systems will prove equally critical in developing the design for Autonomous Warfare as it relates to DL.20 Increasing the offensive capability of smaller groups of warships is one of DL’s main functions (if not the main function). A key enabler to this is the ability to provide ISR-T in a manner that reduces risk to the organic vessels. The concern is that targeting requires the ability to detect, track, and classify enemy vehicles – which oftentimes requires emission of electronic signals that will alert the enemy. Unmanned systems have the ability to provide ISR-T while reducing the risk for organic vessels to reveal their location. Autonomous Warfare will leverage the use of unmanned systems in all three maritime domains (air, surface, and sub-surface). Anything less would unnecessarily limit the potential for delivering maximum offensive firepower while minimizing risk to the organic platforms. Furthermore, critics should note that the U.S. Navy’s adversaries are making similar advances in unmanned systems.21 The bottom line is that underutilization of unmanned systems will be detrimental to DL. The effectiveness of DL as an operational concept depends on the effective employment of unmanned systems.

Providing A Frame of Reference

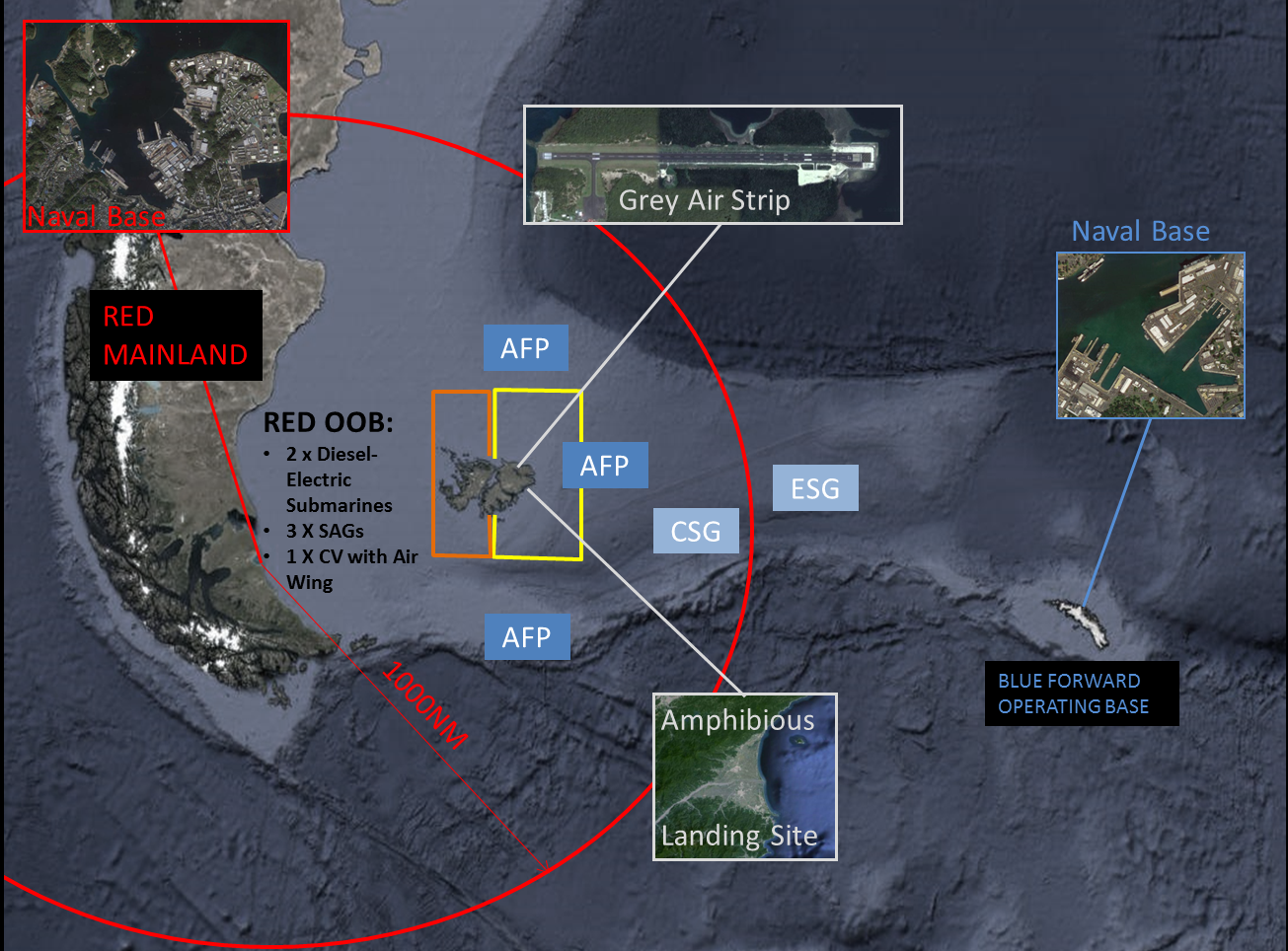

The following hypothetical situation offers a frame of reference for the remainder of the Autonomous Warfare argument.22 The goal is to show that Autonomous Warfare will optimize DL employment in a scenario where multiple BLUE AFPs must operate in the same AO against multiple RED force SAGs and other RED forces.23

The area depicted in Figure 1 represents the AO for the given scenario. Country GREY is an abandoned island and has an airfield that BLUE forces want to capture to facilitate follow-on operations against RED. The Joint Force Maritime Component Commander (JFMCC) receives the task of capturing the airfield. As such, he establishes two objectives for his forces: establish sea control on the eastern side of the island (indicated in yellow) to support an amphibious landing in preparation for seizing the airfield, and establish sea denial on the western side of the island (indicated in orange) to prevent RED from achieving the same.

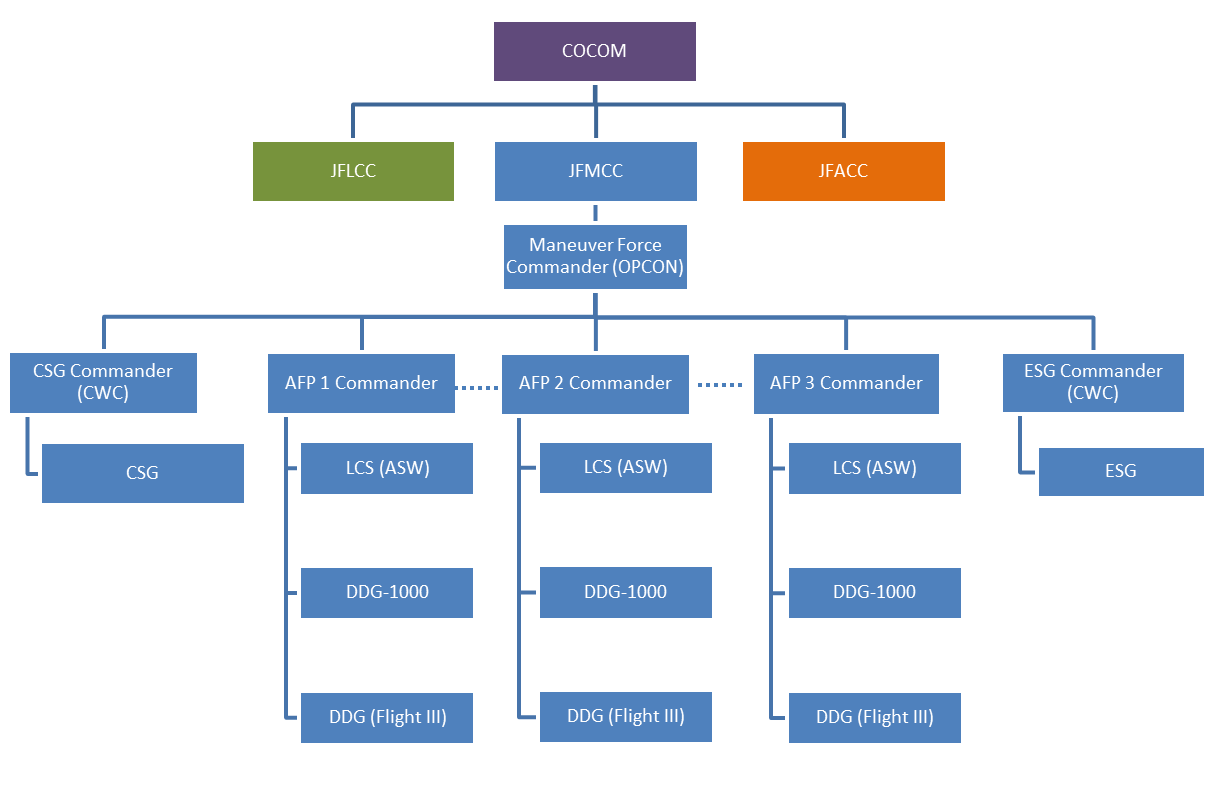

BLUE’s Order of Battle (OOB) consists of one carrier strike group (CSG), one expeditionary strike group (ESG), and three AFPs. Each AFP is comprised of an ASW capable Littoral Combat Ship (LCS), a Flight III Arleigh Burke-class destroyer, and a Zumwalt-class destroyer. Together, each AFP is capable of the full range of offensive and defensive measures needed to defeat enemy targets in each of the three maritime domains.25 RED’s OOB consists of one CSG, three SAGs, and two diesel-electric submarines. RED has a more difficult targeting problem than if BLUE elected to concentrate its forces, since BLUE distributed them across the AO utilizing multiple AFPs capable of delivering offensive firepower in all three traditional warfare domains. How then should BLUE best establish its C2 structure? Will that C2 structure continue to function while operating under emissions control (EMCON) and in the event RED is able to degrade or deny BLUE communications? What roles should unmanned systems play in optimizing ISR-T while minimizing risk to the organic platforms? By developing and applying the concepts of Autonomous Warfare, BLUE will operate with a C2 construct that enables more autonomous action at the lower levels. Additionally, BLUE will leverage the use of unmanned systems, relieving the stress of ambiguity in a communications denied environment.

A Traditional Approach for Applying the CWC Concept to DL

One could argue that AFPs operating under the DL construct should follow a traditional CWC C2 structure, which provides a counter-argument for the Autonomous Warfare approach. The CWC concept attempts to achieve decentralized execution and is defensively oriented. The composite warfare commanders direct the various units of a task force on a warfare-specific basis.26 By delegating oversight of each warfare area to lower levels, the command structure avoids creating a choke point at the task force commander level (the CWC). This configuration is “structurally sound – if not brilliant” for its inherent capacity to simplify the offensive and defensive aspects of maritime warfare down to each warfare area.27 AFPs employed in the scenario described above would then operate under the cognizance of the different warfare commanders on a warfare-area basis. These AFPs are simply groups of disaggregated forces forming a distributed network that would otherwise maneuver as a concentrated assembly around the carrier.

Putting the given scenario into action and using the C2 structure depicted in Figure 2, to what degree are the APFs enabled to achieve the given objectives? BLUE AFPs are stationed as shown in Figure 1 and will attack any RED forces attempting to contest BLUE’s sea control in the yellow box. BLUE also has a continuously operating defensive combat air (DCA) patrol stationed west of the sea denial box to prevent any RED advancements towards island GREY. Just as BLUE forces get into position, RED attempts to form a blockade of the island by sending two SAGs, each escorted by a submarine, around the north and south ends of the island. The first indication of a RED attack comes from a synchronized ASCM salvo from unidentified targets (they were fired from RED’s submarines) followed by radar contact on the RED SAGs from BLUE UAVs providing ISR-T. BLUE’s distributed AFPs, fully enabled by commander’s intent, are capable of self-defense and defeating the RED forces.

Close coordination with the warfare commanders is not required. Each AFP commander understands that in order to maintain sea control to the east, he must dominate in the air, sub-surface, and on the surface. The CWC remains informed as the situation develops and the warfare commanders provide additional guidance for regrouping following the destruction of enemy threats. Thus, a traditional CWC approach to commanding and controlling AFPs provides the opportunity for centralized planning with decentralized execution with respect to DL. Further efforts to decouple the C2 of the AFPs from the task force as a whole could jeopardize unity of effort amidst a complex maritime contingency. AFPs should not be totally self-governing since “uncontrolled decentralized decision-making is just as likely to result in chaos on the battlefield” as no command and control at all.28

An Autonomous Warfare Approach for DL Command and Control

The traditional CWC approach for DL C2 works in this case only because the given scenario is relatively simple. Uncertainty and adversity (often times referred to as fog and friction) are problems that commanders will enduringly have to overcome in wartime. “A commander can no more know the position, condition, strength, and intentions of all enemy units than the scientist can pinpoint the exact location, speed, and direction of movement of subatomic particles.”29 The best he can do is generate an estimate of the situation based on the information available. In the previous scenario, RED’s COA was generic; BLUE should anticipate this type of COA to a degree, relative to RED’s overall plan of attack. Replaying the scenario with two slight yet profound modifications will show that we should not think of the traditional CWC C2 concept as a universal solution. An Autonomous Warfare approach will simplify managing the fog and friction of war from an operational C2 perspective and maximize AFP combat potential.

Assume the forces available and assigned objectives on each side are unchanged. In this case, RED brings to bear more of its A2/AD capabilities, including jamming BLUE’s communications network. Additionally, RED has sufficient ISR capabilities to determine the location and composition of BLUE’s AFPs. As a result, RED concentrates its forces to the north in an attempt to annihilate BLUE’s AFPs in series. The AFP to the north is now overwhelmingly outmatched. Similar to the previous scenario, BLUE’s first indication of a RED attack is a salvo of ASCMs fired from RED’s submarines. As a result, the LCS is damaged to the extent that it provides no warfare utility. Because communications are jammed, the remaining AFP forces cannot communicate with the CWC and his warfare commanders on the carrier to receive guidance on how to proceed. How does the affected AFP protect itself with the loss of its primary ASW platform? Does the traditional C2 structure allow the affected AFP to coordinate directly with the adjacent AFP for re-aggregation? Collectively, the remaining AFPs still offer the commander adequate capability to thwart the RED attack. This is not to say that Autonomous Warfare completely nullifies the principles of the CWC concept. Autonomous Warfare simply optimizes the principles behind the CWC concept for DL.30

The following is an analysis of how an Autonomous Warfare approach to C2 for AFPs optimizes the combat potential that DL offers – especially in an A2/AD environment. A notional Autonomous Warfare DL C2 structure is provided in Figure 3. Each AFP would have an assigned AFP commander and designated alternate. Tactical decision-making would occur at the AFP level. Communications requirements would be drastically reduced. The delegated C2 structure obviates the need for dislocated command and control – AFPs under the auspices of the CSG. Thus, the “search-to-kill decision cycle” is completely self-contained.31 This degree of autonomy avoids the particular disadvantages of centralized command indicated in the previous example. Autonomous Warfare enables the AFP commander to make best use of his available forces based on the tactical situation and in pursuit of the assigned objectives. Furthermore, Autonomous Warfare prioritizes local decision-making founded on training, trust, mission command, and initiative rather than top-down network-centric command and control.32

There is an additional significant advantage to having a more autonomous C2 structure. Although the operational commander could assign each AFP a geographic area of responsibility, they could combine forces and disagreggate as necessary in the event of a loss or an encounter with concentrated enemy forces. In the second scenario above, two AFPs could coordinate directly with each other to counter the larger enemy compliment. They could avert the challenges and ambiguity of reaching back to the centralized commanders altogether as long as they maintained accountability for their assigned areas of responsibility. In the case where the LCS was eliminated, the AFP commanders should have the autonomy to adapt at the scene to accomplish the objective without seeking approval for a seemingly obvious response to adversity.

Another reason why a more flexible, autonomous C2 structure is imperative for DL forces is that there is no “one-size-fits-all” AFP.33 The operational commander may assign different combinations of platforms based on the assets available and the given objectives. The harsh reality of war is that ships sink. The doctrine in place must allow for rapid adaptation with minimal need to communicate to higher authority. The Current Tactical Orders and Doctrine for U.S. Pacific Fleet (PAC-10) during World War II captures this notion best: “The ultimate aim [of PAC-10 was] to obtain essential uniformity without unacceptable sacrifice of flexibility. It must be possible for forces composed of diverse types, and indoctrinated under different task force commanders, to join at sea on short notice for concerted action against the enemy without interchanging a mass of special instructions.”34

Optimizing DL with Unmanned Systems

The aggressive employment of unmanned systems is the second feature of Autonomous Warfare through which the U.S. Navy should optimize DL. “It is crucial that we have a strategic framework in which unmanned vehicles are not merely pieces of hardware or sensors sent off-board, but actual providers of information feeding a network that enhances situational awareness and facilitates precise force application.”35 While there are many applications for unmanned systems, Autonomous Warfare exploits the information gathering and dissemination aspects to increase the lethality of organic platforms. By enhancing the capacity to provide localized and stealthier ISR-T using unmanned systems, AFPs will assume less risk in doing the same and can focus more on delivering firepower.36 The examples provided below solidify this assertion.

Submarines provide a healthy balance of ISR and offensive capabilities to the operational commander. A submarine’s ability to remain undetected is its foundational characteristic that gives friendly forces the advantage while “complicating the calculus” for the enemy.37 There is a significant tradeoff between stealth and mission accomplishment that occurs when a submarine operates in close proximity to its adversaries or communicates information to off-hull entities. By making use of UUVs, AFPs can still rely on stealthy underwater ISR-T while allowing the organic submarine to focus on delivering ordinance. In the given scenario, a small fleet of UUVs could be stationed west of the island and provide advanced warning of the approaching enemy forces. If traditional manned submarines took on this responsibility, they would likely have to engage on their own as the risk of counter-detection might outweigh the benefits of communicating. AFPs themselves could remain stealthy and focus on efforts to defeat the enemy.

While UUVs provide additional support in the undersea domain, UAVs are potential force multipliers in the DL application for two additional reasons. A cadre of unmanned aircraft could provide valuable ISR-T and line-of-sight (LOS) communications to further enable AFP lethality.38 From an ISR-T perspective, AFPs could deploy UAVs to forward positions along an enemy threat axis to provide indications and warning (I&W) of an advancing enemy target or SAG. Their smaller payloads means they can stay on station longer than manned aircraft, and they eliminate the risk of loss to human life. Additionally, the benefits of providing LOS communications are numerous. LOS communication is particularly advantageous because it eliminates the need to transmit over-the-horizon, which becomes exceedingly risky from a counter-detection perspective as range increases.39 A UAV keeping station at some altitude above the surface could provide LOS communications capability among various vessels within the AFP that are not necessarily within LOS of each other. Further, a UAV at a high enough altitude may afford the opportunity for one AFP to communicate LOS with an adjacent one. The level of autonomy these AFPs can achieve, and therefore lethality, only improves as battlespace awareness becomes more prolific and communication techniques remain stealthy.

Just as UUVs and UAVs offer significant advantages to Autonomous Warfare, there is great value in the application for USVs in the surface domain. Take for instance the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s (DARPA) anti-submarine warfare (ASW) Continuous Trail Unmanned Vessel (ACTUV). This stunning new technology has the capability of tracking the quietest diesel-electric submarines for extended periods.40 If this type of vessel was available to provide forward deployed ASW capabilities in the second scenario described above, the likelihood of RED submarines attacking BLUE would have diminished. While this particular USV would operate primarily for ASW purposes, it is completely feasible that the designers could equip the ACTUV with radar capabilities to provide additional ISR against air and surface threats. USVs simply provide an additional opportunity for operational commanders to provide ISR-T to weapons-bearing platforms.

The Combined Effect

The true value intrinsic to Autonomous Warfare stems from the combined effect of an appropriate C2 structure for DL that enables autonomous action and the force multiplier effect the operational commander realizes from unmanned systems. Distributed Lethality has serious potential for raising the status of our surface force as a formidable contender to one of deterrence. In an age where leaders measure warfighting capacity in technological advantage, it is refreshing to see an emerging concept that applies innovative thinking to warfighting techniques with the Navy we have today. A more autonomous C2 structure at the operational level will afford DL forces the flexibility to rapidly deliver offensive measures as contingencies develop. “By integrating unmanned systems in all domains, the U.S. Navy will increase its capability and capacity,” especially with respect to DL.41

Recommendations

It will take both time and effort to achieve an optimized Distributed Lethality construct through Autonomous Warfare. The following recommendations will assist in making this vision a reality:

1. There is risk that by disconnecting the AFPs from the CSG from a C2 perspective, the CSG becomes more vulnerable and unnecessarily sacrifices situational awareness. The Surface Warfare Directorate) N96 and the Distributed Lethality Task Force should further evaluate the tradeoffs associated with implementing a more autonomous C2 structure to DL at the operational level. Additionally, this paper proposes an operational C2 structure for DL. The conclusions derived from this paper should support further development of tactical level C2 for DL.

2. While many of the unmanned systems mentioned above are currently operational or under development, there is limited analysis of how to employ them in a Distributed Lethality environment. OPNAV N99 (Unmanned Warfare Systems), working in conjunction N96 and the DL Task Force, should consider incorporating unmanned systems within the DL concept as outlined above.

3. The U.S. Navy should conduct wargames and real world exercises to both validate the strengths of Autonomous Warfare and identify areas for improvement. Wargames will help refine Autonomous Warfare from a developmental approach. Naval exercises have two benefits: realistic testing provides proof of concept with the same force that will go to war. They also provide the opportunity to practice and inculcate new concepts.

4. Doctrine should begin to foster a culture of Autonomous Warfare throughout the U.S. Navy. The battlefield is becoming more volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous. The more we enable our highly trained and experienced officers to think and act autonomously, the greater combat potential the Navy will realize. Submarines, by nature, operate this way on a continuous basis. Other warfare communities will benefit from having the ability to operate in a more autonomous manner. As Autonomous Warfare represents a paradigm shift from a “connected force” towards a more autonomous one, the U.S. Navy must understand and embrace Autonomous Warfare before implementing it.

Conclusion

Distributed Lethality’s impending contribution to the joint force depends on its ability to maintain flexibility. An autonomous C2 structure allows for localized assessment and force employment, rapid adaptation in the face of adversity, and the ability to combine forces and re-aggregate as the situation dictates. Aggressive employment of autonomous vehicles only enhances these principles. Unmanned systems operating across the maritime domains will provide valuable ISR-T and facilitate localized decision-making, while minimizing risk to the organic platforms. By providing a means of stealthy communication among ships within an AFP or even between adjacent ones, Autonomous Warfare fosters an environment of secure information sharing. Less need to reach back to a command node means that DL forces can spend more time taking the fight to the enemy and less time managing a complicated communications network.

Maritime warfare is a complex process. Characterized by uncertainty and ambiguity, no weapon, platform, or operating concept will eliminate the fog and friction of war. Commanders must mitigate these challenges by setting the conditions necessary for their subordinate leaders to prosper. Commanders at the tactical level earn the trust of their superiors before taking command. We should not compromise that trust by establishing rigid command and control structures that ultimately inhibit the subordinate’s ability to perform as trained. Applying the autonomous approach to C2 for distributed lethality will enable AFPs to operate in accordance with commander’s intent and is in keeping with the initiative to promote Mission Command throughout the U.S. Navy.

LT Coleman Ward is a Submarine Officer who is currently a student at the Naval War College. The preceding is his original work, and should not be construed for the opinions of views of the Department of Defense, the United States Navy, or the Naval War College.

Featured Image: The prototype of DARPA’s ACTUV, shown here on the day of its christening. Image Courtesy DARPA.

1. Timothy Walton and Bryan McGrath, “China’s Surface Fleet Trajectory: Implications for the U.S. Navy,” in China Maritime Study No. 11: China’s Near Seas Combat Capabilities, ed. Peter Dutton, Andrew Erickson, and Ryan Martinson, (U.S. Naval War College: China Maritime Studies Institute, February 2014), 119-121, accessed May 5, 2016, https://www.usnwc.edu/Research—Gaming/China-Maritime-Studies-Institute/Publications/documents/Web-CMS11-(1)-(1).aspx.; Peng Guangqian, Major General, People’s Liberation Army (Ret.), “China’s Maritime Rights and Interests,” in China Maritime Study No. 7: Military Activities in the EEZ, ed. Peter Dutton, (U.S. Naval War College: China Maritime Studies Institute, December 2010), 15-17, accessed May 12, 2106, https://www.usnwc.edu/Research—Gaming/China-Maritime-Studies-Institute/Publications/documents/China-Maritime-Study-7_Military-Activities-in-the-.pdf.

2. Walton and McGrath, “China’s Surface Fleet Trajectory: Implications for the U.S. Navy,” 119-121.

3. Thomas Rowden, Peter Gumataotao, and Peter Fanta, “Distributed Lethality,” U.S. Naval Institute, Proceedings Magazine 141, no. 1 (January 2015): 343, accessed March 11, 2016, http://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2015-01/distributed-lethality.

4. Rowden et. al. “Distributed Lethality.”

5. James Bradford, America, Sea Power, and the World (West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons, 2016), 339.

6. John Richardson, Admiral, Chief of Naval Operations, A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, January 2016), 6.

7. Matthew Hipple, “Distributed Lethality: Old Opportunities for New Operations,” Center for International Maritime Security, last modified February 23, 2016, accessed May 12, 2016, https://cimsec.org/distributed-lethality-old-opportunities-for-new-operations/22292.

8. Thomas Rowden et. al., “Distributed Lethality.”

9. U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Coast Guard, A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower (Washington, D.C.: Headquarters U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard, March 2015), 9.

10. Thomas Rowden et. al, Distributed Lethality.

11. United States Navy, Naval Operations Concept 2010 (NOC): Implementing the Maritime Strategy (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2010), 54-55.

12. United States General Accounting Office, Comprehensive Strategy Needed to Improve Ship Cruise Missile Defense, GAO/NSIAD-00-149 (Washington, DC: General Accounting Office, July 2000), p. 5, accessed April 14, 2016, http://www.gao.gov/assets/230/229270.pdf.

13. Andrew Erickson and David Yang, “Using the Land to Control the Sea?,” Naval War College Review 62, no. 4, (Autumn 2009), 54.

14. United States Navy, Naval Operations Concept 2010: Implementing the Maritime Strategy, 54-56.

15. Andrew S. Erickson, Personal summary of discussion at “China’s Naval Shipbuilding: Progress and Challenges,” conference held by China Maritime Studies Institute at U.S. Naval War College, Newport, RI, 19-20 May 2015, accessed April 25, 2016, http://www.andrewerickson.com/2015/11/chinas-naval-shipbuilding-progress-and-challenges-cmsi-conference-event-write-up-summary-of-discussion/.

16. Thomas Rowden et. al., “Distributed Lethality.”

17. United States Navy. Naval Doctrine Publication (NDP) 1: Naval Warfare (Government Printing Office: Washington, D.C. March 2010), 35.

18. This is also referred to as “Mission Command” or “Command by Negation;” U.S. Office of the Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication (JP) 3-32, Command and Control for Joint Maritime Operations (Washington D.C.: CJCS, August 7, 2013), I-2.

19. The Naval War College’s Gravely Group recently conducted a series of three DL Workshops with representation from offices across the Navy and interagency. One of the key findings was that “AFP SAG C2 architecture requires further development in view of information degraded or denied environments.” This paper proposes a notional operational level C2 structure – tactical level C2 is addressed in the recommendations section; William Bundy and Walter Bonilla. Distributed Lethality Concept Development Workshops I – III Executive Report. (U.S. Naval War College: The Gravely Group, December 29, 2015), 9.

20. This paper considers three types of maritime unmanned systems currently employed or under development: Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs), and Unmanned Surface Vessels (USVs).

21. See the below article featuring a newly developed Chinese drone similar to the U.S.’s Predator drone currently employed for operations in the Middle East; Kyle Mizokami, “For the First Time, Chinese UAVs are Flying and Fighting in the Middle East,” Popular Mechanics, last modified December 22, 2015, accessed May 10, 2016, http://www.popularmechanics.com/military/weapons/news/a18677/chinese-drones-are-flying-and-fighting-in-the-middle-east/.

22. This scenario does not represent a universal application for DL.

23. The Rowden “Distributed Lethality”article provides its own “Hunter-Killer Hypothetical” situation while supporting its main argument. However, the scenario is basic and does not afford the opportunity to explore how AFP C2 and unmanned systems would function in a complex maritime contingency.

24. Google Maps, “South Atlantic Ocean” map (and various others), Google (2016), accessed April 14, 2016, https://www.google.com/maps/@-50.3504488,-53.6341245,2775046m/data=!3m1!1e3?hl=en.

25. This is the same AFP force composition suggested in the Rowden Distributed Lethality article “Hunter-Killer Hypothetical” situation; Thomas Rowden et. al., “Distributed Lethality.”

26. For a full explanation of the CWC concept and roles and responsibilities of CWC warfare commanders, see: United States Navy, Navy Warfare Publication (NWP) 3-56: Composite Warfare Doctrine (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, September 2010).

27. Larry LeGree, “Will Judgement be a Casualty of NCW?,” U.S. Naval Institute, Proceedings Magazine 130, no. 10 (October 2004): 220, accessed April 14, 2016, http://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2004-10/will-judgment-be-casualty-ncw.

28. CNO’s Strategic Studies Group (XXII), Coherent Adaptive Force: Ensuring Sea Supremacy for SEA POWER 21, January 2004.

29. Michael Palmer, Command at Sea (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), 319.

30. Jimmy Drennan, “Distributed Lethality’s C2 Sea Change,” Center for International Maritime Security, last modified July 10, 2015, accessed April 14, 2016, https://cimsec.org/?s=Distributed+lethality+c2+sea+change.

31. Jeffrey Kline, “A Tactical Doctrine for Distributed Lethality,” Center for International Maritime Security, last modified February 22, 2016, accessed March 17, 2016, https://cimsec.org/tactical-doctrine-distributed-lethality/22286.

32. Palmer, Command at Sea, 322.

33. Jeffrey Kline, “A Tactical Doctrine for Distributed Lethality.”

34. Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet, Current Tactical Orders and Doctrine, U.S. Pacific Fleet (PAC–10), U.S. Navy, Pacific Fleet, June 1943, pg. v, section 111.

35. Paul Siegrist, “An Undersea ‘Killer App’,” U.S. Naval Institute: Proceedings Magazine 138, no. 7, (July 2012): 313, accessed April 30, 2016, http://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2012-07/undersea-killer-app.

36. Thomas Rowden et. al., “Distributed Lethality.”

37. Ibid.

38. Robert Rubel, “Pigeon Holes or Paradigm Shift: How the Navy Can Get the Most of its Unmanned Vehicles,” U.S. Naval Institute News, last modified February 5, 2013, https://news.usni.org/2012/07/25/pigeon-holes-or-paradigm-shift-how-navy-can-get-most-its-unmanned-vehicles.

39. Jonathan Soloman, “Maritime Deception and Concealment: Concepts for Defeating Wide-Area Oceanic Surveillance-Reconnaissance-Strike Networks,” Naval War College Review 66, no. 4 (Autumn 2013): 89.

40. Scott Littlefield, “Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) Continuous Trail Unmanned Vessel (ACTUV),” Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, accessed April 30, 2016, http://www.darpa.mil/program/anti-submarine-warfare-continuous-trail-unmanned-vessel.

41. Robert Girrier, Rear Admiral, Director, Unmanned Warfare Systems (OPNAV N99), “Unmanned Warfare Systems,” Lecture at U.S. Naval War College, May 11, 2016.

Featured Image: PHILIPPINE SEA (Oct. 4, 2016) The forward-deployed Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS McCampbell (DDG 85) patrols the waters while in the Philippine Sea. McCampbell is on patrol with Carrier Strike Group Five (CSG 5) in the Philippine Sea supporting security and stability in the Indo-Asia-Pacific region. (U.S. Navy photo by Petty Officer 2nd Class Christian Senyk/Released)