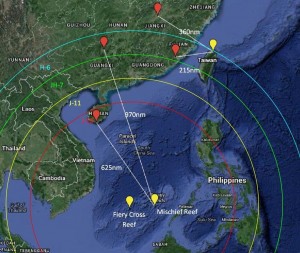

The year 2014 brought new tensions to the South China Sea, particularly as Chinese authorities sought to establish a series of island-like structures in the midst of the disputed Spratly Islands. Such provocative actions, however, are unlikely to generate sufficient political will among the other countries of the region to establish a Political-Security Community under the auspices of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) by the 2015 deadline. But were this collection of ten countries to pool their resources into a security community or even a security alliance, it would be an impressive force and a potential deterrent to aggression in the South China Sea.

In particular, it is worthwhile noting the relative strength of ASEAN coastal defence forces. Some member states, such as Indonesia, possess respectable ‘blue water’ navies, that is to say, they have larger vessels capable of operating in deep waters and engaging in long-range standing battles. Other ASEAN countries, such as the Philippines, have considerable ‘brown water’ navies, forces consisting of small patrol boats which can cruise inland waterways and the shallow waters that weave between tight-knit island chains. But the varied nature of the waters disputed in the South China Sea particularly requires the flexibility offered by corvettes.

Generally, corvettes fall between the Royal Canadian Navy’s Halifax-class frigates and Kingston-class coastal defence vessels in size. But there is much debate as to what constitutes a contemporary corvette. For example, the Royal Omani Navy calls its Khareef-class vessels ‘corvettes’ even though the displacement of each vessel in the class is approximately 2,660 tons. Recent advancements in shipbuilding have also allowed the US Navy to introduce new vessels with substantial displacement but with shallower drafts, meaning the new USS Liberty can approach closer to coastlines than the similarly sized but older Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates.

For the purposes of this analysis, only those vessels with a displacement greater than 100 tons but less than 1,700 tons will be considered corvettes. China’s maritime forces, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), has a substantial number of vessels in this range deployed to Hong Kong and a network of naval bases off the South China Sea. 12 Jiangdao-class corvettes (1,440 tons) are the workhorses of this maritime presence in the region and China may possibly add 3 more vessels of this class by the end of 2015. Beyond the Jiangdao-class corvettes, PLAN’s southern presence includes six Houjian-class missile boats (520 tons) and approximately 80 other missile boats and gunboats of various classes and ranging in displacement from 200 to 480 tons each. This vastly exceeds the quantity and quality of vessels any individual Southeast Asian country could bring to bear in a conflict. But ASEAN’s combined maritime forces could meet the challenge presented by a limited PLAN offensive.

Brunei in particular has emerged as a promising new maritime actor in the region, even actively participating in the 2014 edition of the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC). The Royal Brunei Navy acquired four specially built Darussalam-class offshore patrol ships (1,625 tonnes) from the German shipbuilder Luerssen-Werft, which replaced Brunei’s previous coastal defence workhorse, the Waspada-class fast attack craft (200 tonnes). The Waspada-class vessels have since been decommissioned and donated to Indonesia to be used for training purposes. The introduction of the Darussalam-class greatly upgrades Brunei’s defence capabilities and it will be of interest for Southeast Asian observers to see how Brunei further pursues the modernization of its forces.

The Republic of Singapore Navy has much in the way of heavier frigates and submarines to defend its unique position by the Strait of Malacca, one of the world’s most significant shipping routes. Its corvette-like vessels are also impressive, six Victory-class corvettes (600 tonnes) and 12 Fearless-class offshore patrol ships (500 tonnes), but they are certainly not as new as some of the vessels boasted by Singapore’s neighbours. The Victory-class was acquired in 1990-1991 while the Fearless-class was introduced between 1996 and 1998. Therefore, it will also be of interest to see whether Singapore seeks to obtain any newer vessels which can serve as a bridge in capabilities between the Victory-class corvettes and the heavier Formidable-class frigates.

It is Thailand, the Philippines, and Indonesia that boast the largest complements of corvettes in the region, however. The Royal Thai Navy’s coastal defence is led by two Tapi-class corvettes (1,200 tons) and two Pattani-class offshore patrol ships (1,460 tons), which are joined by two Ratanakosin-class corvettes (960 tons), three Khamrosin-class corvettes (630 tons), three Hua Hin-class patrol boats (600 tons), six PSMM Mark 5-class patrol boats (300 tons), and 18 smaller patrol boats and fast attack boats of varying capabilities but all rather aged. The Philippines and Indonesia both have vast island chains within their respective territories, requiring corvettes and smaller patrol vessels just as much for counter-trafficking and counter-piracy operations as for countering conventional maritime forces. The Philippine Navy possesses one Pohang-class corvette (1,200 tons), two Rizal-class corvettes (1,250 tons), nine Miguel Malvar-class corvettes (900 tons), and three Emilio Jacinto-class corvettes (700 tons). Indonesia tops out ASEAN’s array of corvettes with three Fatahillah-class corvettes (1,450 tons), 16 Kapitan Patimura-class corvettes (950 tons), and 65 other missile boats and gunboats with a displacement of approximately 100-250 tons.

It is Thailand, the Philippines, and Indonesia that boast the largest complements of corvettes in the region, however. The Royal Thai Navy’s coastal defence is led by two Tapi-class corvettes (1,200 tons) and two Pattani-class offshore patrol ships (1,460 tons), which are joined by two Ratanakosin-class corvettes (960 tons), three Khamrosin-class corvettes (630 tons), three Hua Hin-class patrol boats (600 tons), six PSMM Mark 5-class patrol boats (300 tons), and 18 smaller patrol boats and fast attack boats of varying capabilities but all rather aged. The Philippines and Indonesia both have vast island chains within their respective territories, requiring corvettes and smaller patrol vessels just as much for counter-trafficking and counter-piracy operations as for countering conventional maritime forces. The Philippine Navy possesses one Pohang-class corvette (1,200 tons), two Rizal-class corvettes (1,250 tons), nine Miguel Malvar-class corvettes (900 tons), and three Emilio Jacinto-class corvettes (700 tons). Indonesia tops out ASEAN’s array of corvettes with three Fatahillah-class corvettes (1,450 tons), 16 Kapitan Patimura-class corvettes (950 tons), and 65 other missile boats and gunboats with a displacement of approximately 100-250 tons.

Yet it is unclear how much of their forces Indonesia or the Philippines would be able to deploy in the midst of a South China Sea conflict. As mentioned previously, many of these vessels have been used practically as inland patrol vessels. There are also some potential weak links in the chain should ASEAN establish some form of formalized maritime alliance. The Royal Malaysian Navy only offers four Laksamana-class corvettes (675 tons) and an array of 16 smaller missile boats and gun boats that could generally only be used to harass Chinese forces. Burma certainly has an impressive force in its own right – consisting of three domestically produced Anawratha-class corvettes (1,100 tons), six Houxin-class missile boats (500 tons), 10 5 Series-class missile boats (500 tons), and 15 Hainan-class gunboats (450 tons), but the military junta has already demonstrated that it will remain aloof from territorial disputes in the South China Sea and generally supports China’s policy toward Southeast Asia.

The Royal Cambodian Navy is in shambles, consisting solely of five outdated Turya-class torpedo boats (250 tons), five Stenka-class patrol boats (250 tons), and a lone Shershen-class fast attack boat (175 tons). But Cambodian authorities would be just as disinclined to engage in defence sharing as their Burmese counterparts. During Cambodia’s 2012 ASEAN chairmanship, Cambodian officials consistently interfered in efforts by other ASEAN member states to reach a common position on the South China Sea’s territorial disputes. Given the understanding on security issues shared between Cambodian and Chinese officials, as well as China’s status as Cambodia’s largest source of foreign investment and aid, it is apparent that Cambodia has relatively no need for the security guarantees ASEAN could provide as a regional counter-balance to China.

Vietnam is the unpredictable factor in the region. The Vietnam People’s Navy has a few corvettes of its own, including a Pauk-class corvette (580 tons), eight Tarantul-class corvettes (540 tons), and 23 patrol ships with displacements ranging from 200 to 375 tons. The Vietnamese government has also ordered two more TT-400TP gunboats (450 tons) from domestic shipbuilders with delivery expected in late 2015 or early 2016. This leaves Vietnam with a force perhaps not as sizable as that of Indonesia or the Philippines but with greater capacity to intervene should China seek to settle territorial disputes with Vietnam by force.

As Malaysia will hold the 2015 Chairmanship of ASEAN, the prospects for a maritime force in support of the bloc’s proposed Political-Security Community will depend to some degree on whether Malaysian officials will be willing to show leadership. If Malaysia looks to acquire new vessels and insists on placing maritime security on the agenda of upcoming ASEAN meetings, some arrangement could be struck by the end of the year. But this will require artful diplomacy, especially in the face of Burmese and Cambodian opposition. With Malaysian officials speaking predominantly about the need for a single market in the region and promoting a conclusion to negotiations regarding the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, such a drive for maritime security may not be forthcoming.

Paul Pryce is a Research Analyst at the Atlantic Council of Canada. His research interests are diverse and include maritime security, NATO affairs, and African regional integration.

This article can be found in its original form at the

NATO Council of Canada and was republished by permission.