In his inaugural speech as the President of Indonesia, Joko Widodo communicated a vision of prosperity for his country based on a tradition of maritime trade. Indonesia, he said, is to become a sea-going trading power once again. With a new Ministry of Maritime Affairs and a US $6 billion investment in maritime infrastructure, he’s putting his proverbial money where his mouth is. While this seems like an obvious path for archipelagic Indonesia to take, there are very important reasons why this signals a profound shift in the strategic thinking of the country from an internal threat perception to an external one. Although some analysts believe Jokowi’s pronouncement is code for abandonment of Indonesia’s non-alignment policy, it is likely his words had nothing to do with external actors and everything to do with growing confidence in Indonesia’s democracy to effectively address its historically troubled internal security.

In his inaugural speech as the President of Indonesia, Joko Widodo communicated a vision of prosperity for his country based on a tradition of maritime trade. Indonesia, he said, is to become a sea-going trading power once again. With a new Ministry of Maritime Affairs and a US $6 billion investment in maritime infrastructure, he’s putting his proverbial money where his mouth is. While this seems like an obvious path for archipelagic Indonesia to take, there are very important reasons why this signals a profound shift in the strategic thinking of the country from an internal threat perception to an external one. Although some analysts believe Jokowi’s pronouncement is code for abandonment of Indonesia’s non-alignment policy, it is likely his words had nothing to do with external actors and everything to do with growing confidence in Indonesia’s democracy to effectively address its historically troubled internal security.

Understanding this requires a look at the history and culture of Indonesia’s security services. Like many of its counterparts in neighboring states, the Indonesian security apparatus was formed, tested, blooded, and solidified in an environment of internal insurgency. For hundreds of years, Southeast Asian nations (with the exception of Thailand) were caught up in the ebb and flow of colonial domination. In a very short time following the Japanese invasion of the region in December 1941, these nations underwent a rapid decoupling from the colonial system. By 1959 all were newly independent and all except Thailand were on a fairly shaky basis due to the newness of their institutions. Worse, they all suffered from vicious Communist insurgencies formed, trained, and supported by the Allies to counter the Japanese. In some cases, returning colonial powers (French, Dutch, and British) found themselves fighting the very the agents they had trained just a few years earlier. The chickens had come home to roost in a very real and violent way.

The Communists had two weakness: they were not a single, monolithic insurgency but a collection of disconnected national movements (Malayan, Thai, Indonesian, Filipino) vulnerable to defeat in detail, and their core membership was composed primarily of culturally distinct ethnic Chinese minorities. Their ability to blend into the local populations was limited, forcing the Communists to operate in remote, politically marginal areas. Despite this, they posed a very real threat to the stability of the young governments in the five nations that would eventually form the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). By 1967, these nations had had enough and decided they needed a political construct that would enable them to address the problem. The solution was the principle of non-interference enshrined in the founding declaration of ASEAN. This principle allowed member states to define their insurgencies as purely internal problems and to deal with them without fear of interference by other ASEAN member states. In its implementation over the last forty-seven years, the principle of non-interference has been used at times as a cover for the suppression of internal populations through imposition of emergency security measures such as restrictions on freedoms of the press and assembly; common factors in many ASEAN countries. Of course, the best tool for implementing these restrictions is the police. As a result, in many ASEAN countries the police, not the Army, have primacy for both internal and external security. But Indonesia went a different direction, relying more on its military special operations forces (Kopassus and others) than on its police.

Created by the Japanese to fight Dutch-trained Indonesian paramilitary formations (and ultimately the Dutch themselves), the predecessors of the Indonesian Army (TNI) and national intelligence service (BIN) adopted a heavy counter-insurgency focus during their early operations in the Second World War. With the accession of their leaders, Sukarno and Zulkifli Lubis, to political and bureaucratic power, TNI and BIN’s perception of threat from within dominated Indonesia’s strategic landscape until the end of the 20th Century. As TNI’s monopoly on political power quickly eroded after the fall of Suharto in 1998, the emphasis began to shift toward the police. A U.S. legislative prohibition on direct military engagement with individuals accused of human rights violations accelerated the situation. The prohibition disproportionately affected Kopassus after accusations that many of its leaders committed war crimes during the invasion of East Timor in 1975. Decades later, the U.S. failure to engage Kopassus remained problematic for the United States because TNI continued to block access to other Indonesian units, insisting that Jakarta, not the U.S. Congress, would decide which Indonesian formations received priority for mil-mil cooperation. The impasse left the door open for the U.S. State Department to become the lead U.S. agency for security assistance to Indonesia. Through its Anti-Terrorism Agency (ATA), the State Department drove the formation and training of the now famous police counterterrorism unit, Densus 88,[1] known for its spectacular successes against a number of the country’s most wanted international terrorists. By 2007, with hotspots in Timor and Irian Jaya temporarily quiet, Indonesia’s police seemed to be firmly in control of internal security, allowing the country’s military and political leadership to begin thinking outwardly.

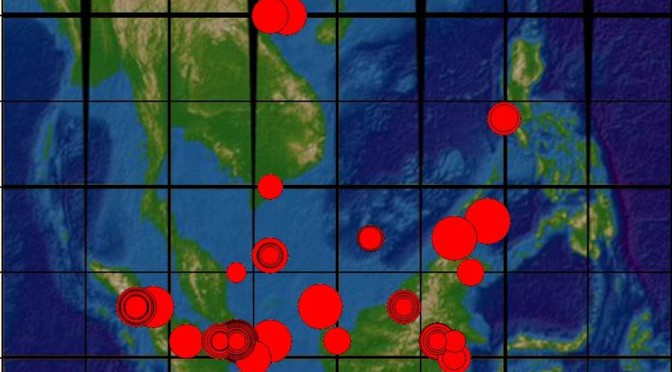

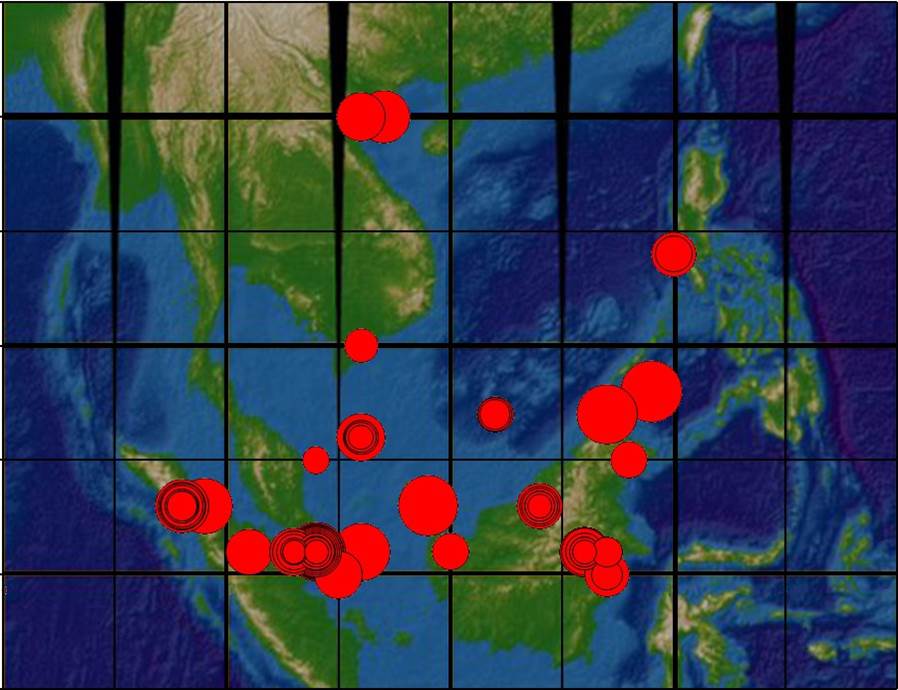

It is in this context that Jokowi’s pronouncement makes sense. Navies do not have great utility against insurgencies and it would not be feasible or advisable to emphasize naval power while under threat from within. While some happily interpret this shift to be aimed squarely at China, whose territorial claims in the South China Sea affect Indonesia’s energy rich Natuna Island, this is probably wishful thinking. China’s brushes with Natuna are a very recent development in what is a much older strategic context. Therefore we should not view such a shift as a bold break from strategic concepts of the past, rather we should take it as a reflection of Indonesia’s changing security situation going all the way back to the Japanese invasion in 1941. While it’s probably inaccurate to portray this as evidence of Jokowi’s greatness and vision, we can take heart that a shift to the sea is evidence that a mature, stable Indonesia has indeed arrived and is here to stay.

Lino Miani is a US Army Special Forces officer, author of The Sulu Arms Market, and CEO of Navisio Global LLC. Views expressed in this article are definitely not the views of the US Government, the U.S. Army, or the Special Forces Regiment.

[1] The name Detacmen Khusus 88, or Densus 88 for short, is reportedly the result of a misinterpretation of the English acronym for Antiterrorism Agency (ATA) by a senior Indonesian police official.

Dean Cheng joins us to discuss China. Like a flourless brownie, this podcast is dense and delicious. We hit China’s goals and perspectives: From the Chinese “status quo”, to the South China Sea, to India, to the use of crises as policy tools. If you want to see behind the headlines, this is your podcast.

Dean Cheng joins us to discuss China. Like a flourless brownie, this podcast is dense and delicious. We hit China’s goals and perspectives: From the Chinese “status quo”, to the South China Sea, to India, to the use of crises as policy tools. If you want to see behind the headlines, this is your podcast.