The Southern Tide

Written by W. Alejandro Sanchez, The Southern Tide addresses maritime security issues throughout Latin America and the Caribbean. It discusses the challenges regional navies face including limited defense budgets, inter-state tensions, and transnational crimes. It also examines how these challenges influence current and future defense strategies, platform acquisitions, and relations with global powers.

“The security environment in Latin America and the Caribbean is characterized by complex, diverse, and non-traditional challenges to U.S. interests.” Admiral Kurt W. Tidd, Commander, U.S. Southern Command, before the 114th Congress Senate Armed Services Committee, 10 March 2016.

By W. Alejandro Sanchez

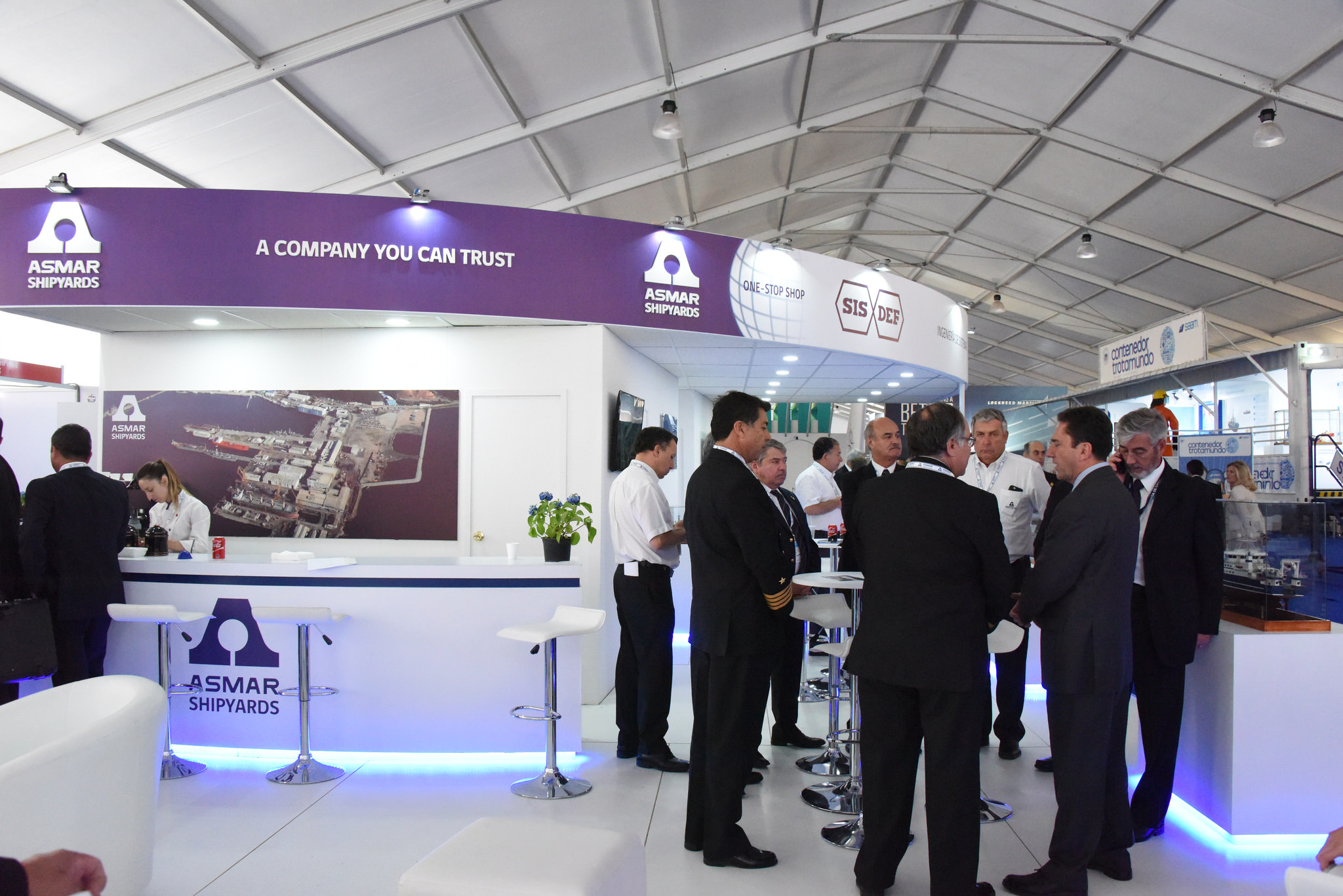

Chile organized the 10th Exponaval exhibition from 29 November – 2 December. The arms fair brought dozens of defense companies to northern Chile, where they showcased their latest maritime defense technology with the hope of securing new contracts. Arms fairs are a common event in the defense industry and they regularly take place in locations across the world, hence the success of Exponaval is particularly relevant as it will help Chile, and Latin America, cement its place in the global arms fair circuit.

Exponaval 2016

The Chilean government and Navy give great importance to Exponaval (full name Exhibición y Conferencia Internacional Naval y Marítima para Latinoamérica) as exemplified by the participation of President Michelle Bachelet, who gave a speech on 29 November to officially open the arms fair. The country’s defense minister and military authorities were also present. Unsurprisingly, during her speech, President Bachelet took a moment to praise her nation’s state-run shipyard Astilleros de la Marina (ASMAR) as it is constructing, with support from the Canadian company Vard, a new ice breaker for the Navy, which is scheduled to be completed in 2018. Exponaval 2016 was held at the at the Concon naval base in Viña del Mar, northern Chile. It is also important to note that the recent arms fair was actually a two in one event, as the 10th Exponaval was also the 5th Trans-Port (full name, Exhibición de la Industria Marítima Portuaria para Latinoamérica), an exhibit of port industries in Latin America.

As for the type of technology that was exhibited, some examples include Russia’s Rosoboronexport, which displayed “Project 12150 Mangust fast patrol boats, the Varshavyanka-class (Project 636) submarines and Amur 1650 class submarines among other vehicles.” A number of British companies were also present, as Mercopress news agency explains that “companies exhibiting on the Department of Trade’s Defence and Security Organisation’s stand include: Leafield, SEA, MOD Disposals Agency and Ultra Electronics. Other UK companies exhibiting include BAE Systems, MBDA, Qinetiq, Kelvin Hughes, Lloyds Register and Thales.”

Additionally, there were also important developments among Latin American maritime defense industries. Case in point, a representative from Colombia’s Corporación de Ciencia y Tecnología para el Desarrollo de la Industria Naval Marítima y Fluvial (COTECMAR) told the defense news agency IHS Jane’s that “a joint programme between Brazil, Colombia, and Peru to develop a new river patrol ship is now under way, with design work expected to conclude in the second half of 2017.” The project dates back to 2015, but it is an important development that there is already a (still somewhat distant) deadline for the completion of the design.

Apart from the sales booths, there were several technical presentations via which experts shared their knowledge. According to Exponaval, the presentations included representatives from renowned defense companies like Navantia, MBDA Missile Systems, SAAB Group as well as Chile’s ASMAR.

Even more, the Chilean Navy had prominent participation in the fair, as it carried out exercises for the audience. This included a simulation in Valparaiso Bay of a vessel carrying radioactive material that is taken over by terrorists, where Chilean naval forces demonstrated how they would react to this hypothetical crisis.

Other Latin American Arms Fairs

It is worth noting that other Latin American countries also have arms fairs, though Exponaval stands out as it focuses on maritime defense technology. For example, Chile organizes another arms fair for aerial technology, the FIDAE-International Air & Space Fair (Feria Internacional del Aire y del Espacio). As for other regional states, Brazil organizes the LAAD Security–Feira Internacional de Segurança Pública e Corporativa (International Fair of Public and Corporate Security); Colombia has the Expodefensa International Fair of Defense and Security (Feria Internacional de Defensa y Seguridad); while Peru organizes the SITDEF–International Show for Defense Technology and Disaster Prevention (Salon Internacional de Tecnologia para la Defensa y Prevencion de Desastres).

Like with Exponaval, other governments and militaries provide support for these fairs in their respective nations. For example, while Exponaval 2016 took place at the Concon naval base, SITDEF 2017 will reportedly be held at the Peruvian Army’s headquarters in Lima.

Significance

What is the importance of Latin America organizing arms fairs? This author would argue that the main objective is to demonstrate that Latin America should not be regarded as a sole importer of military technology, but also a producer and a “showcase center” where deals can be made. President Bachelet voiced a similar idea in her welcome message as she stressed how this arms fair “allows a meeting between [suppliers] from the naval defense and maritime industry with official delegations from Latin American navies and the port agencies from other countries.”

In a 22 August commentary for CIMSEC entitled “The Rise of the Latin American Shipyard” the author discussed how various Latin American nations are constructing their own naval platforms and are even attempting to sell them to foreign customers. Since said commentary was published there have been new developments in the region: Colombia’s COTECMAR has signed a contract with Honduras and another one with Panama for logistic multipurpose vessels; Peru’s Servicios Industriales de la Marina (SIMA) has reached an agreement with Bolivia to sell its navy a riverine hospital ship; finally Ecuador’s shipyard Astilleros Navales Ecuatorianos (ASTINAVE) on 10 November “announced it is to construct three passenger boats for the Panama Canal Authority.”

Hence, regional arms fairs are particularly important for Latin American defense industries as they they allow for opportunity to showcase their products to regional navies and international firms in order to attract future sales. The aforementioned deals by ASTINAVE, COTECMAR and SIMA highlight that intra-regional naval platforms sales are already happening, and future arms fairs will benefit these companies in their eternal quest for new customers; hence it should not come as a surprise that SIMA and COTECMAR were present in Exponaval.

This brings us to the obvious question: to what extent do the exhibitions and meetings made during these arms fairs, such as Exponaval, result in actual contracts? Exponaval naturally summarized the recent fair as a success, explaining how over 140 company experts gave presentations, while putting the number of attendees at over nine thousand visits. Additionally, regional navies deployed some of their platforms, including Argentina’s corvette Robinson; Brazil’s Niteroi-class frigate Constitucion; Mexico’s patrol vessel Centenario de la Revolución; while the United Kingdom deployed the frigate HMS Portland and the tanker RFA Gold Rover.

As for contracts, Exponaval’s declared in a statement that deals were made for more than USD $800 million, but “this amount is related to the projects that the participating navies have in development for the next few years.” Hence, we will have to wait and see if in the coming months announcements are made about contracts between Latin American navies and maritime defense companies, and whether they can be traced back to Exponaval 2016.

Final Thoughts

The Exponaval 2016 arms fair which recently took place in northern Chile should be regarded as a success for local government and maritime forces. It was reportedly well-structured, with over a hundred companies showcasing their maritime defense products, it hosted thousands of visitors, and even featured visiting warships from friendly nations. Santiago also demonstrated the accomplishments of its state-run shipyard ASMAR as well as the professionalism of its naval forces. Ultimately, we will have to wait to see if, indeed, Exponaval (not to mention other Latin American defense fairs) can reliably serve as a place where suppliers and customers can meet and ultimately reach sales agreements.

W. Alejandro Sanchez is a researcher who focuses on geopolitical, military, and cyber security issues in the Western Hemisphere. Follow him on Twitter: @W_Alex_Sanchez.

The views presented in this essay are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of any institutions with which the author is associated.

Featured Image: Model submarine at Exponaval 2016 (Exponaval 2016 photo)