By Dmitry Filipoff

CIMSEC sat down with Captain Mark Vandroff to solicit his expert insight into the complex world of acquisition and the future of the U.S. Navy’s destroyers. CAPT Vandroff is the Program Manager (PM) of the U.S. Navy’s DDG 51 program, the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer, which is the most numerous warship in the U.S. Navy. In Part One, CAPT Vandroff discussed the differences in warship design between the Flight IIA and Flight III destroyer variants, acquisition best practices, and the Navy’s Future Surface Combatant Study. In the second and final part of our interview, CAPT Vandroff goes into depth on his publications Confessions of a Major Program Manager published in U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, and An Acquisition System to Enable American Seapower, published on USNI News and coauthored with Bryan McGrath. He finishes with his thoughts on building acquisition expertise in the military and his reading recommendations.

In your U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings article Confessions of a Major Program Manager, you used an elaborate metaphor to illustrate your responsibilities. What are the various stakeholder pressures in your program and how do you manage them?

I have great stakeholders, each of whom are great at doing their job, which is part of the challenge, and part of the fun. A program manager is responsible for turning money and a requirement into a product. Each of the other stakeholders is responsible for making sure a specific part of that process happens properly. I have been totally blessed in my five years as PMS 400D. I have had excellent contracting officers. When my contracting officer signs the contract, she is responsible to ensure what we do complies with the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) and all the other regulations governing contracting. I compete for the resources of the NAVSEA contracting directorate with every other program that NAVSEA has to support. There are more programs with more good ideas of things we could do than we have contracting officers to go execute them. I have a pressure there where I am trying to get a contracting officer to either move at the speed I want to move, or to be flexible for things I want to do for the program, but he or she’s got a responsibility to make sure that the contract bears scrutiny.

In SEA 05, our technical directorate, the Navy has a technical warrant holder for ship design called the ship design manager who brokers all the other technical requirements. I have one each for both Flight IIA and Flight III. They are responsible for a safe and effective design that meets the requirement, but not necessarily for the full range of mission accomplishment. So when it comes to funding I might say “I know that’s a requirement, but its really not going to deprive us of a critical capability, and I need the money somewhere else in the program to do something else.” That is the classic program manager to ship design manager tension. The classic PM to tech warrant friction is when we want to do something different. If I think it makes sense to do something different, and if the technical community thinks it doesn’t make sense, we spend time resolving it.

So why did I write that article? People who want to be program managers, they spend their time building those relationships so you can have good communication and understanding. When you get there, I know what my contracting officer, ship design manager is going to be worrying about. I understand my supervisor of shipbuilding, who is responsible for the quality of the shipbuilder’s product. I know what they are responsible for and what their concerns are.

Every time we make a Government Furnished Equipment (GFE) or Contractor Furnished Equipment (CFE) decision; if that decision is GFE usually it means the Navy has another program manager. So I don’t buy computers or communications systems for a DDG 51 directly, I send money to SPAWAR (Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command) and they deliver the program those products. They’ve got their own set of challenges. I am trying to fit them into the schedule and the budget that I need to get a DDG 51 delivered on time and on cost. They have got their own challenges and it is not easy what they are trying to do with MOUS (Mobile User Objective System) or CANES (Consolidated Afloat Networks and Enterprise Services). That is hard on their part because they are trying to deliver the very best technology possible for those IT systems in a short amount of time. A good program manager spends his or her time building those relationships so you always know what is going on with all those different players so you can get people together and get agreement.

When I went to the Naval Academy I majored in engineering, and I became an engineering duty officer, and then I became a program manager, and then I end up as everyone’s psychologist. “The therapist is in” is what you end up doing in order to get a ship built. The end of that article is that you can be frustrated with it, but after a while you can find that you love it. I don’t know if psychology is my next career after the Navy or not, but the point of the article is that you have to spend your time building relationships with all those different stakeholders because each of them is part of a puzzle to get something as complicated as a ship built and built properly.

In the article published on USNI News, An Acquisition System to Enable American Seapower, that you co-authored with Bryan McGrath, how did you come up with your recommendations for reform?

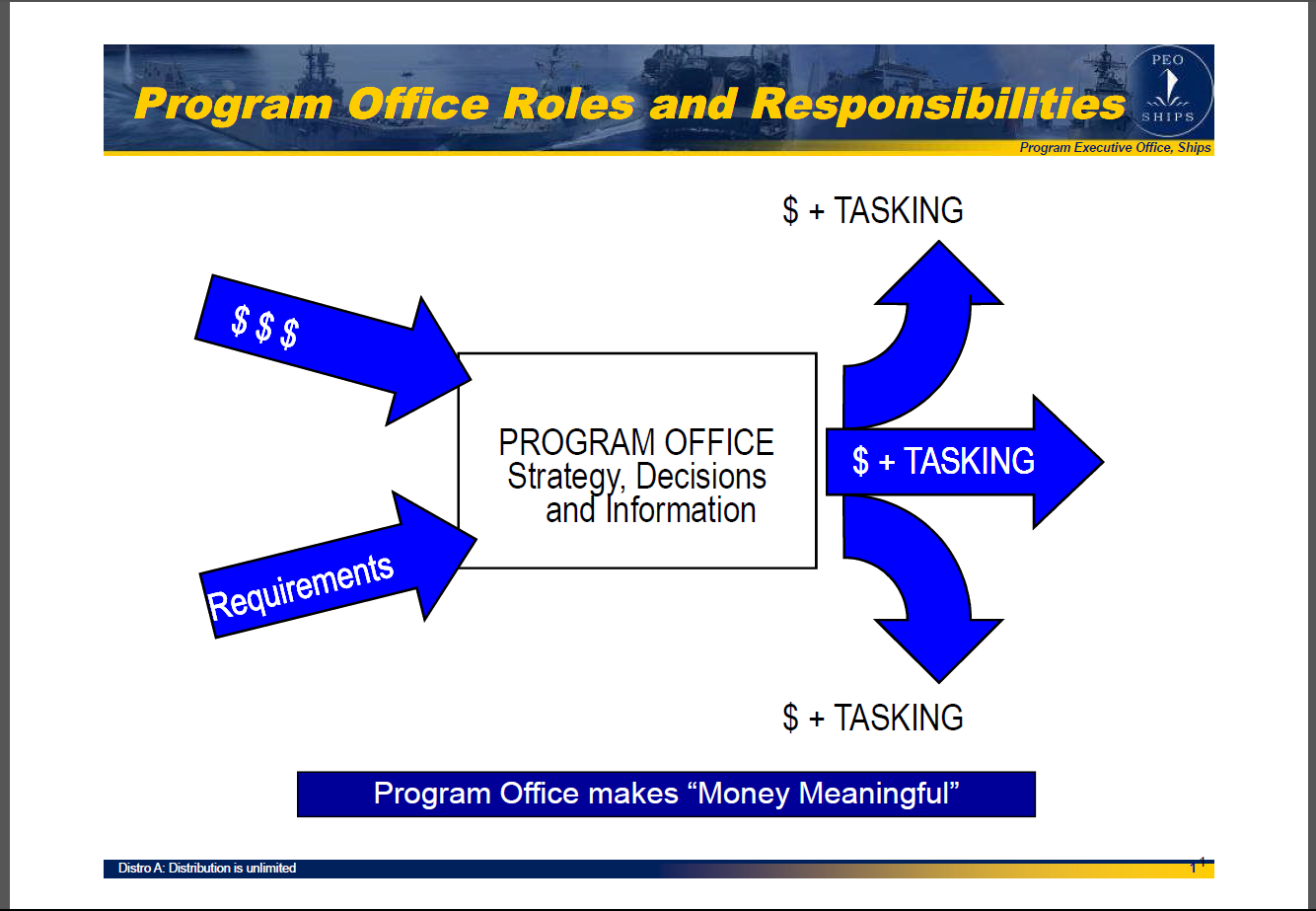

I wanted to state the problem right. Let’s think about acquisition from the perspective of a program office.

Requirements: This is the JCIDS (Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System). This is the hardest of all of them, and it is the least regular. It is the most unbound because this is the one that is threat based. Your enemies in the world come along at irregular intervals and give you undefined or hard to define problem sets. And they don’t do that when Congress is ready to appropriate money, or when you’ve decided you’ve engineered a really good solution. They show up with new problems for that. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs runs this.

Tasking: At the end of tasking a product appears. All the taskings together add up to a product. This was written by USDAT&L (Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics), DOD 5000 on how do program offices spend their money? Whether that’s contracting, the FAR, or whether that’s the way one part of the government tasks another part of the government, all of that is apart of the DOD 5000 and its regulations, and the service regulations under that. The Navy has the Navy 5000. So this is your milestone, milestone B-C, or in the Navy this is two pass-six gate. This is your system for how you do tasking, whose permission do you need to do the tasking, how do you write the contract, the statement of work, and design reviews.

This was written by engineers. If you go to Exxon today and ask Exxon to share their system on how they decide when to explore for oil, once they’ve explored and found it how do they make a decision on how to get it out, once it’s out how do they get it into production, and then how to get it to people who want to buy, it will look a whole lot like the Navy’s two pass-six gate system, and not by accident. It’s the way any engineer would approach a problem. You start by defining the problem, what do you need. Can I go buy that yes/no, what do I need to invent to have it, if I invent it I better test it to make sure it works, how do I build it efficiently, how do I put it into production, and how do I dispose of it safely. It is the exact same life cycle whether it’s a tank, airplane, warship, or oil rig. It is the way an engineer approaches a problem. Notice this is not how the requirements or appropriations folks approach their problem, they have their own cycles.

Resources: What system controls the money? PPBE (Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution) controls that. It was written the way it is to service Congress. The events in here are coordinated to the schedule of the Congress of the United States i.e. when does the budget go, when do the committees mark, etc. All of these things sync up in time with how Congress appropriates money. If Congress appropriated money monthly or in five year increments, the PPBE would be different. The tasking and who runs the PPBE is the OSD Comptroller. The OSD Comptroller writes it because of the way Congress does their business.

The biggest point to my article is that you are not going to get all of these perfectly synced because the tasking is an engineering based process, the PPBE is a congressional appropriation based process, and the requirements process is threat based and our ability to react to that.

The problem is that there is no unified decision making in any of this. There is supposed to be, and certainly lots of senior DoD officials try. The Vice Chiefs are constantly inviting Secretary Kendall to their reviews, and vice versa. They try and piece themselves together. The point of our article is, it would really help to find someone, for a given set of programs or capabilities, to tie all these people together. One entity, somewhere. Some people say it’s the service chief, some say the service secretary, some say for a given program make an entity within OSD. My point is that for the program office, the influx of requirements, the influx of money, and the outflux of tasking need to be drawn together. It needs a single unified purpose behind it, or they will be at cross-purposes. How do you see these cross-purposes? It’s taking more time, costing more money, and all the things that can happen in a program that are undesirable. Of course human error is an inherent part of this.

I would like people to be working in a system at the center of all this, where the inputs and the outputs are coordinated and synchronized to the best possible level. When you read the article, you may see requirements and tasking getting synchronized to appropriations. This is part of the constitution. You synchronize to your appropriations cycle, and you need to put one entity in charge of this. You need someone to be responsible for the process in its entirety whether a service chief or a service secretary, but it needs to be at an appropriate level of seniority and who can do all of this for a set of programs. That was the point of the article.

What do you think about the current state of acquisition expertise in the military and how can it be improved?

We have had a lot of talk about that and it goes back and forth, if you’re going to have military people doing acquisition. That’s an “if,” not a “must.” Unlike fighting in combat which is a uniquely military mission, buying stuff for the military could be done and is done often, and done very well, by government civil servants. You do not necessarily need uniformed military although all four services like to have military personnel at some points in the process.

The challenge there is finding the right balance between acquisition experience and operational experience. Different services and different subcommunities within services have explored different paths for that. I think the Navy continues to look at that, and continues to try and ask ourselves “are we getting it right?” For leadership positions in acquisition there is the current DAWIA (Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act) policies that we are implementing, I believe it is now eight years of acquisition experience and four years in a program office to be a major program manager.

I think a program manager needs to understand how a program office works. For someone in the military, you don’t want to make them a program manager if they have never served in a program office. I think program managers also need to understand their product, and that can take a lot of different forms. In shipbuilding, for example, we usually want someone to have done a tour as a supervisor of shipbuilding to understand how the product gets built. For some of the weapons systems that can be how the product gets built or how it gets certified at a place like NSWC Dahlgren, or how it gets supported in-service at a place like Port Hueneme, or maybe out at Raytheon in Tucson where we have people on-site managing Raytheon’s missile production. You have to have some experience in the field and see how it happens. A program manager also needs to have lived the aforementioned acquisition processes. If you add that up, that amounts to about nine years worth of work. That is what is recommended for a military program manager as the standard.

The next question is how much operational experience do you want on top of that. We have a couple models in the Navy. In my case I am an engineering duty officer. I have two operational tours, about six-seven years of sea duty. I have served in multiple program offices, different tours at supervisor of shipbuilding, so I have a breadth of experience there. There are folks in the unrestricted line community who may only have the minimum of the acquisition experience but have more operational experience, maybe five or six more years of sea duty than me. That may have included command at the commander level, an O-5 command, and that gives them a different perspective. I think the Navy continues to go back and forth and figure out what the right balance between those two models is, and to make sure we identify folks to grow their talent early enough and give people those experiences so by the time they are running a program they have built those relationships I mentioned. They understand the people and understand what that other stakeholder’s job is like because they dealt with it before and know their legitimate concerns and motivations across all those different competencies that go into building a ship.

It takes a while. We can roll that nine year minimum into an unrestricted line officer’s career and come up with a certain kind of officer, you can roll it into someone who has had more acquisition experience and less operational and come up with a different person. I think either one can work, and the Navy keeps going back and forth and tweaking what that sweet spot is. But if we are going to have military officers doing acquisition, we have to balance acquisition experience with operational experience. If the PM does not bring much operational experience, then it might be more efficient to have a civilian doing it. The benefit of the military is to bring operational experience into the acquisition world.

What books do you recommend?

The best book I read in the past year and a half is General Stanley McChrystal’s Team of Teams. I cannot recommend it too highly. It is a fabulous book on leadership and thinking through problems, especially in today’s highly networked world. That’s the newest book I recommend, the oldest book I recommend is Aristotle’s Ethics. In his very first paragraph, he makes the famous statement “All human activity aims at some good.” The different activities he lists include, and I am paraphrasing here, “the purpose of medicine is to bring health,” that “the purpose of economics is to bring wealth,” and that the purpose of “strategy is to bring victory.” He also adds “and the purpose of shipbuilding is to build a ship.”

Why did Aristotle say that? Aristotle lived in a unique society. He lived in a democracy that was a maritime power which depended upon that maritime power for both its security and trade prosperity. What is the United States? It is a democracy, it is a unique society, and it is a maritime power that depends upon its maritime power for economic prosperity and its security in the world. That is why I think, although written almost 2500 years ago, what Aristotle has to say is still relevant to us in the United States today. He was worried about shipbuilding as an informed citizen, and I think informed citizens should still be worried about shipbuilding today for the same reasons they worried about it in Aristotle’s Athens.

Thank you for your time Captain.

My pleasure.

Captain Vandroff is a 1989 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy. With 10 years as a surface warfare officer and 16 years as an engineering duty officer, he is currently the major program manager for Arleigh Burke – class destroyers.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. Contact him at Nextwar@cimsec.org.

Featured Image: CAPT Vandroff at the Keel Authentication Ceremony of USS john Finn DDG 113 at Huntington Ingalls Shipbuilding in Pascagoula, Miss.