By Alex Calvo and Pol Molas

The logistical side to the US Pivot to the Pacific. One of the aspects not often discussed of the US “Pivot to the Pacific” is that it is not just combat forces (US Army, US Air Force, US Navy and US Marine Corps) moving, but also the Military Sealift Command, which constitutes the cornerstone of logistical support for US operations all over the world. Just to get an idea of its size, if this command’s ships belonged to another nation they would be the fourth-largest navy in the world. As a consequence, NATO European members must reinforce their logistical capabilities.

The best-prepared naval forces to achieve this are the Royal Navy (the Royal Fleet Auxiliary, to be more precise) and France’s Marine Nationale. Germany is beginning to boost her global-scale force projection capabilities, limited to date due to well-known historical reasons. Now, the economic crisis and ensuing budget cuts are providing added impetus to the development of shared capabilities. While there is a growing pressing to achieve this, it is nothing new. For example, we can mention the United Kingdom and the Netherlands as a model of force integration, with their UK/NL Landing Force. By the way, there is a Catalan angle to this. Anglo-Dutch cooperation in amphibious operations dates back to the 1704 landing in Gibraltar, where a 350-strong Catalan battalion under General Bassett also took part. Therefore, should a future Catalan contingent join the UK/NL Landing Force, they would just be coming back home. Another significant example are the three Baltic Republics, which combine their naval forces in the BALTRON (Baltic Naval Squadron).

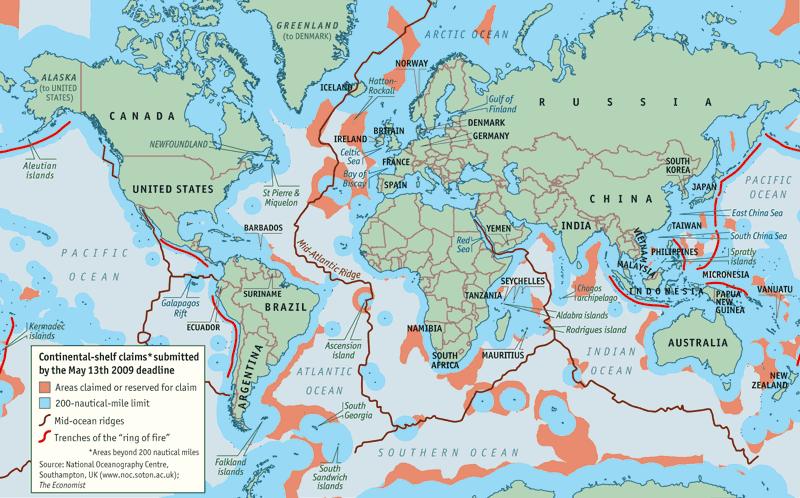

Barcelona and Tarragona Harbours: two key dual-use infrastructurs in the Western Mediterranean. When we talk logistics, one of its key elements are ports. It is precisely when countries are pondering how to cut costs that the concept of dual-use infrastructures comes to the fore. In this area, the ports of Barcelona and Tarragona can make a much greater contribution that they do at present. Right now, other than the occasional port visit by the US and other Allied navies, they are not the permanent home of any Spanish Navy unit. Furthermore, despite healthy growth in terms of tonnage, much of their necessary connecting infrastructure remains incomplete. In particular, a European gauge connection to the French railway network. However, in addition to featuring in plans for a future Catalan Navy, they could also become an strategic asset for NATO, being home to a portion of the Atlantic Alliance’s logistical units in the Mediterranean Theatre.

It is not just a matter of size. Both infrastructures are located in areas sporting a concentration of industry and transportation links. These links must certainly be improved, in line with the EU’s 2013 decision to confirm the “Mediterranean Corridor” as a key element of the Old Continent’s transportation networks. This label refers to a railroad transportation axis connecting cities and ports along the Spanish southern and eastern seaboards to France. Since most EU member states also belong to NATO, there is no reason to expect any discrepancy between the two organizations when it comes to the logistical map of Europe.

The benefits on the civilian economic front of completing this infrastructure have already been explained at length by myriad economists, such as for example Ramon Tremosa, currently serving as member of the European Parliament, who has written extensively on the project and worked hard as a lawmaker to see it come to fruition. This explains the support of the French Government and the European Commission, which have rejected alternative proposals to drill a tunnel in the Central Pyrenees, connecting Spain and France through the Aragon region. From a naval logistics perspective, this alternative plan would not have benefited NATO and allied navies to the same extent, since it would have meant bypassing Tarragona and Barcelona. The benefits of the “Mediterranean Corridor”, on the other hand, also extend to the field of defense. For example, should NATO’s Response Force (NRF) need to project one of its battle groups in a crisis scenario, we may ask ourselves whether Toulon, Marseilles, and Naples harbors would suffice. While it would not be impossible, it may make it harder to label it a rapid-reaction force.

The Pivot to the Pacific rests on a strong NATO and a secure Mediterranean. The US Pivot to the Pacific, and more widely the growing coordination among the maritime democracies in the Indian-Pacific Ocean Region, are based on the assumption that the Mediterranean will be secured by NATO. Thus, any move reinforcing security in this body of water has a direct, positive, impact on the struggle for the rule of law at sea in the Indian-Pacific Region. A struggle, let us be realistic about it, that is surely to be bitterly tested in the future ahead. As a historical reminder of the connection between the two regions, we may mention the failed British strategy to defend Singapore. Built at a time of scarce resources, the naval base was supposed to provide the necessary facilities for a strong naval and air force to be moved in the event of a crisis, without the expense involved in a permanent presence. However, the need to protect home waters, the Atlantic, and the Mediterranean, meant that all that London could send were HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse, sunk by Japanese land-based naval aircraft in the South China Sea in the opening days of the Second World War in the Pacific.

Conclusions. Barcelona and Tarragona are key dual-use facilities in the Western Mediterranean, whose naval logistical potential to date has not been fully exploited. Their worth will multiply once the “Mediterranean Corridor”, backed by Paris and Brussels, is completed. Their potential contribution to NATO is growing as pressure on defense budgets forces countries to get as much bang for the buck as possible, and as moves to reinforce the Indian-Pacific Ocean Region make it imperative to fully secure the Mediterranean.

Alex Calvo is a guest professor at Nagoya University (Japan) and member of CIMSEC, Pol Molas is a naval analyst and regular contributor to the Blau Naval blog