By Scott Cheney-Peters

Follow @scheneypeters

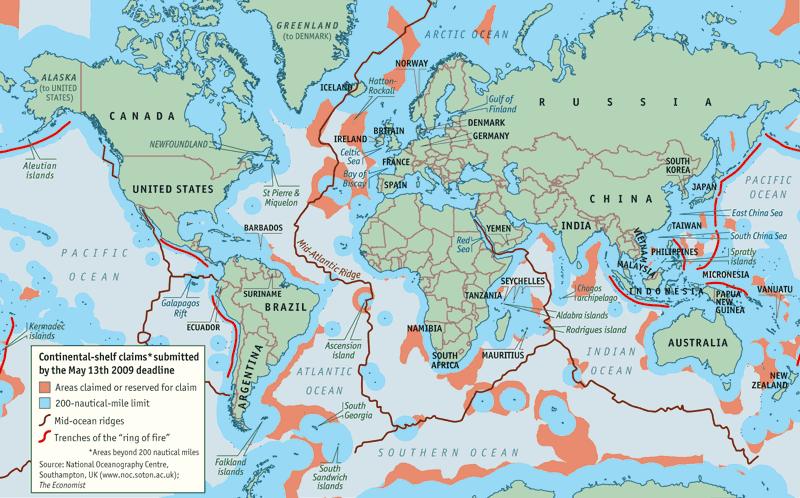

After months of speculation and signaling the U.S. has undertaken Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) to protest the claimed rights of Chinese-occupied “artificial islands” in the South China Sea at Subi and Mischief Reef by sending the USS Lassen within 12nm of the reefs. Several of our colleagues and members have written recently about the context, the legal aspects, the recent history, and response to the FONOPS. I recommend reading them all but wanted to offer a few additional thoughts below:

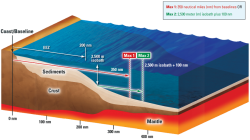

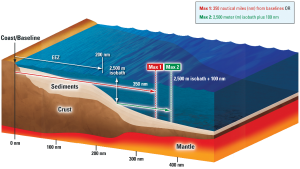

This was a necessary move to both reassure America’s allies and partners in the region of America’s commitment and to uphold common sense interpretations of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). What many pieces of analysis gloss over is that even though UNCLOS is pretty clear that the reclamation doesn’t turn reefs into islands or give them the rights of islands, interpretations of international law – if contested – must be backed up by words and actions. Otherwise the counter-vailing view gains acceptance as customary international law.

This was a necessary move to both reassure America’s allies and partners in the region of America’s commitment and to uphold common sense interpretations of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). What many pieces of analysis gloss over is that even though UNCLOS is pretty clear that the reclamation doesn’t turn reefs into islands or give them the rights of islands, interpretations of international law – if contested – must be backed up by words and actions. Otherwise the counter-vailing view gains acceptance as customary international law.

The reported several-years’ pause in conducting these types of freedom of navigation operations (FONOPS) in the South China Sea may have been done to try and convince the Chinese to stand-down from their position. Not being privy to the internal administration deliberations I’m not sure if there was a good reason why it took so long to change course and resume FONOPS, but the delay created the risk that the resumption would create a major incident. This is why shortly before it occurred it appeared that the US was trying to prevent surprise from contributing to the risk of an incident by not only warning of the pending FONOPS but very specifically identifying which ship would conduct it and where.

While necessary for the reasons stated above, these FONOPS are unlikely to change the situation unless the Chinese overreact, something I don’t expect to happen. This doesn’t mean China will do nothing, however, and their response may consist of one or more approaches. One thing Chinese officials have long hinted at before the FONOPS occurred was that they would be used as justification for pre-planned actions, such as declaring an ADIZ over the South China Sea or the “militarization” of the reclaimed islands. Another possible action is mirroring the supposed provocation of the American FONOPS by conducting something perceived by the Chinese to be similar – such as additional transits near Alaska. Direct responses to further FONOPS will likely include shadowing of US naval vessels by Chinese naval vessels, as occurred with the LASSEN, and could include electronic or physical interference, as indicated by Chinese media – both much more dangerous and likely to escalate the situation.

Lastly, U.S. officials reportedly indicate that additional FONOPS will be conducted to protest Vietnamese and Philippines excessive claims in the coming weeks. These are not new protests, nor are FON activities in various forms limited to the region but in fact are used to protest claimed excessive maritime rights around the world, from Ecuador to India.

Scott Cheney-Peters is a surface warfare officer in the U.S. Navy Reserve and founder and Chairman of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC). He is a graduate of Georgetown University and the U.S. Naval War College, a member of the Truman National Security Project, and a CNAS Next-Generation National Security Fellow.