By Robert C. Rubel

Thomas Friedman’s 13 April New York Times opinion piece recounts an interview with John Arquilla, a distinguished former grand strategy instructor at the Naval Postgraduate School. In explaining Ukraine’s impressive military performance in the face of the Russian invasion, Arquilla cites three rules of new age warfare from his book Bitskrieg: The New Challenge of Cyberwarfare, and their application is quite fitting. If these rules concocted for cyberwarfare apply to ground warfare, might they also apply to warfare at sea? If so, what are the implications?

Arquilla’s three rules are as follows:

- Many and small beats large and heavy

- Finding always beats flanking

- Swarming always beats surging

These rules are few and simply stated – generally a good thing when it comes to parsing a complex phenomenon like war. And they do have a true new age feel to them; terms like many, small, finding, and swarming convey the notion that information technology in the form of micro-miniaturization makes even small weapons more powerful. That said, there are words in the rules that raise alarms; categorical words like always convey a superficiality that experienced warfighters and analysts immediately suspect. But nonetheless, it is worth exploring how these rules could impact future naval warfare and fleet design.

Rule 1: Many and Small Beats Large and Heavy

As missiles become faster, longer range, smarter, and even harder to defeat, they might very well challenge the traditional relationship between capability and tonnage. The introduction of potent hypersonic missiles adds saliency to the application of this rule to naval warfare, calling into question the vulnerability of large capital ships such as nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. The most powerful weapons of yore, namely major caliber guns and jet aircraft, required large hulls to support their operations and the remainder of fleet design followed from there. However, missiles tend to break the relationship between weapon power and ship displacement, just as they break the relationship between capability and cost; hundreds of thousands of Tomahawk missiles could have been bought for the same price as the F-35 program.

A missile-centric fleet design that took advantage of the new opportunities might consist of numerous smaller units of various types. The nascent U.S. Marine Corps concept of small detachments operating anti-ship missile launchers from dispersed locations reflects that logic as does – albeit incompletely – the U.S. Navy’s concept of Distributed Maritime Operations. Operating a highly dispersed force would complicate enemy targeting.

Moving past the categorical nature of the rule, we must also acknowledge that operating dispersed forces in the maritime environment is not the same as small groups of soldiers toting Javelin anti-tank missiles. For starters, deploying and sustaining a dispersed force will be more difficult than current battle groups composed of large ships. Then there is the matter of command and control. Since the conceptual emergence of “network-centric warfare” in the late 1990s, the vision of a dispersed, heterogeneous force knitted together by a network has been at least the tacit basis for communications and data processing developments. The various challenges to realizing this vision have not yet been overcome, and so adopting highly dispersed operations before such a comprehensive and resilient battle force network is operational would require a new and more sophisticated approach to mission command. These are just a few concerns that make application of the rule at sea less than straightforward. Nonetheless, the inherent character of modern missiles does add credibility to the rule when it comes to naval warfare.

Rule 2: Finding Always Beats Flanking

Putting aside the word always, the rule would not at first glance seem to apply at sea, where ships can maneuver “fluidly” as it were. There is perhaps some whiff of flanking in the concept of threat sector. If battle group defenses, say the positioning of escorts or combat air patrol stations is oriented on an expected threat sector, then an enemy that can succeed in approaching outside of that sector might be regarded as flanking. But this is speculative. However, if we think of flanking at sea as achieving an operational level ambush, we can see it exhibited in historic naval campaigns and battles. At Midway, the US task force took a position to the northeast of Midway Island and succeeded in ambushing the Japanese carrier force. In March of 1805 Admiral Horatio Nelson took a “secret position” between Sardinia and Mallorca hoping to ambush Admiral Villenueve’s French fleet if it sailed toward Italy or Egypt.

Now, in the Midway case, the Japanese forces did not find the American task force until too late and suffered the loss of three aircraft carriers (Hiryu was sunk later, after the US task force had been located). In Nelson’s case the ambush would have worked because Villenueve, even though his orders were to escape the Mediterranean via Gibraltar, had planned to sail east of Mallorca, which would have led him into Nelson’s trap. However, a merchant ship had seen Nelson’s force and reported it to Villenueve, who altered his route to west of Mallorca. If the Japanese had located the American task force earlier, the results of Midway would likely have been much different. Both examples reveal the critical importance of finding first.

Anyone familiar with the writing of legendary Naval Postgraduate School Professor Wayne Hughes’ and his principle of “strike effectively first,” will immediately see the connection with this rule. Getting in an effective first strike requires finding effectively first, and no naval ambush can occur if this does not happen. This in turn requires enemy scouting efforts are ineffective and the enemy commander remains ignorant of the ambushing force. The act of finding and striking effectively first should not be viewed in momentary isolation or as singularly decisive, because command decision-making at all levels will be critical in maneuvering these finding and striking forces prior to successful engagements. So, while the term flanking does not translate well into naval warfare, its implied dependency on maneuver does carry over.

Rule 3: Swarming Always Beats Surging

The third rule is a bit trickier to relate to naval warfare. Arquilla states in the interview that “You don’t need big numbers to swarm the opponent with a lot of small smart weapons.” The implication is that instead of achieving mass or concentration of force using symmetrical weapons, tanks versus tanks, for instance, forces can make asymmetric attacks by using smart weapons not tied to big platforms, i.e., many teams of Javelin shooters versus columns of Russian tanks. In that sense the third rule seems to be merely a restatement of the first. That said, swarming is a term that has taken on new meaning in an age of smart drones. The notion of a large number of small things “besetting” a target conveys Arquilla’s implicit meaning.

Picking this apart a bit more, let’s regard surging as the assembling of a force or capability that is greater than that of the enemy it is confronting – the traditional concentration of force, either at the operational or tactical level. Swarming, on the other hand, implies coming at a particular enemy target from everywhere, whether the besetting attack is centrally planned or whether it is based on the self-synchronization of the individual swarming entities. Surging implies a numerical relationship between the opposing forces, one presumably outnumbering the other. Swarming involves no such relationship – it is about having enough individual units to beset a target from all sides either simultaneously or in rapid sequence. Swarming seems generally to apply to the tactical, unit or even weapons level.

An instantiation of swarming in naval warfare would involve the use of deception drones or missiles meant to saturate an enemy ship’s defenses. The US Navy devised an elemental form of swarming tactics in its attempt, after the showdown with the Soviet Fleet in the Mediterranean in 1973, to generate some kind of anti-ship capability, which it had let lapse after World War II. The tactic involved a formation of five aircraft approaching the enemy ship at low level. Flying in close formation it would look like one blip on enemy radars. At a certain point the aircraft would starburst, fanning out in different directions and then turning back in based on careful timing such that they would arrive at their bomb release points in rapid succession. The maneuver was meant to confuse the target ship’s fire control systems and at the end saturate defenses such that at least one aircraft would be able to reach its release point.

Surging implies Lanchestrian calculations that reveal the superiority of numbers; swarming is about creating confusion, using relatively large numbers for sure, but not in the strict relative sense addressed by Lanchester’s equations.1 This point is widely appreciated: China is thought to have developed large numbers of deceptive drones and missile warheads that can deploy decoys to achieve confusion and saturation of US Navy ship defenses.

At the present state of the art, achieving swarming would still require either a large number of launching platforms or engagement from relatively close range. If the Navy did adopt the concept of a flotilla of smaller missile combatants there would have to be significant covering and deception efforts to get them into position to use their missiles and decoys. On the other hand, cover for a salvo of long range missiles might be provided by long range bombers that could launch decoys in addition to anti-ship missiles. However, the central point is that swarming – no matter how it is achieved – offers potential relief from the brute force logic of Lanchester’s equations.

Taking the Rules to Sea

If we combine Arquilla’s three rules, what do we get in terms of a picture of future naval warfare? First, it would seem that we could articulate a rather more nuanced rule: the force that can find, evaluate and target first will have a significant advantage. However, if both sides forces are composed of smaller, dispersed missile-shooting units, be they surface, air or subsurface, both fleets would likely be more resilient if they had to absorb a first strike. A naval battle would then become a geographically dispersed, cat-and-mouse game of progressive attrition. The game board would include not only the ocean, including the air above, adjacent land features and the depths below, but space, cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum. If swarming attacks were fully developed and employed, the only defense would be to avoid detection through stand-off, stealth, or deception. The set piece naval battle would be replaced by an extended campaign of raids and quick strikes, followed by rapid retreat into sanctuaries or out of range. Knowledge of the tactical and operational situation would be intermittent and mostly fragmentary. The chances of putting together a large and coordinated missile salvo from dispersed units would be small, assuming the enemy is able to disrupt friendly networks in some way, so each unit must be armed with missiles that have the ability to create their own terminal swarms. This would allow for a form of swarming on a larger scale; dispersed units would operate on the basis of mission orders, and a swarming rule set, including a precise definition of calculated risk appropriate to the situation. The operation of German U-boat wolf packs in World War II constituted a nascent form of such a battle.

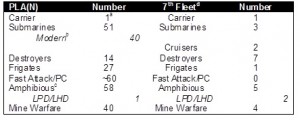

Neither the formalized collision of lines of dreadnoughts nor the long range groping of carrier battles are likely to characterize future naval warfare. Arquilla’s three rules imply intermittent and dispersed missile-based campaigns of attrition that will extend over days, weeks or even months; the quick and decisive clash at sea could very well be a thing of the past. If this is so, fleet design must be rethought. Missiles, not tactical aircraft dropping bombs, will be the decisive weapons. The Fleet’s offensive power must be distributed among a larger number of platforms, and its doctrine must include ground and long-range air elements. Logistics for such a force that would allow it to remain in contested areas for extended periods must be worked out. Sensing and processing as well as resilient communications will, in effect, become the new “capital ship” of the Navy, as these will allow the offensive missiles to be most effective in accordance with Arquilla’s rules. There will be a continuing need for some residual legacy forces, as the Navy has a multi-faceted and global mission, but for high-end naval combat in littoral waters, a force designed around Arquilla’s rules will be needed in order to fight at acceptable levels of strategic risk.

Does all this have implications for traditional naval concepts like command of the sea and sea control? Almost certainly. Command of the sea has heretofore meant that the weaker navy either could not or would not directly confront the stronger. This allowed the stronger navy to use the seas for its own purposes and deny such use to the weaker. But if sea power becomes atomized, composed of many missile shooting units, then the deterrent basis for command of the sea evaporates. We see a nascent form of this already with the Chinese land-based DF-21 and 26 anti-ship ballistic missiles. While this condition may initially be limited to specific littoral regions, the continued development of naval forces shaped by Arquilla’s rules would imply that command of the sea could be contested by weaker navies farther and farther out at sea, to the point that the concept loses meaning. Sea control, the function of protecting things like merchant traffic or geographic points, would become the paramount concept and demand the utmost in dispersion of forces – strategic, operational and tactical. Thus navies desiring to produce for their nations the traditional benefits of command of the sea would have to be composed of numerous and therefore cheaper units so that naval power would be available at any and all points needed, whenever that need arose.

Chaos theory shows how complex phenomena can emerge from simple rule sets. If we tease out their threads, Arquilla’s three simple rules for new age warfare seem to be able to perform that trick with regards to naval warfare and the design of navies. We might look askance at the categorical tone he uses in those rules, but that should not cause us to dismiss them as new age fluff. Some basis for fleet design is needed beyond the narrow incorporation of the next better radar or aircraft, and these three rules seem to be worth considering in that endeavor.

Robert C. Rubel is a retired Navy captain and professor emeritus of the Naval War College. He served on active duty in the Navy as a light attack/strike fighter aviator. At the Naval War College he served in various positions, including planning and decision-making instructor, joint education adviser, chairman of the Wargaming Department, and dean of the Center for Naval Warfare Studies. He retired in 2014, but on occasion continues to serve as a special adviser to the Chief of Naval Operations. He has published over thirty journal articles and several book chapters.

Endnotes

1. In its simplest form it is Aa2 = Bb2 where A and B equal the quality of the respective forces; a and b represent the number of forces. This reflects the dominance of numbers in calculating the outcome of engagements.

Featured Image: KEKAHA, Hawaii – Artillery Marines from 1st Battalion, 12th Marines escort a Navy Marine Expeditionary Ship Interdiction System launcher vehicle ashore aboard Pacific Missile Range Facility Barking Sands, Hawaii, Aug. 16, 2021. (U.S. Marine Corps photo)