The Red Queen’s Navy

Written by Vidya Sagar Reddy, The Red Queen’s Navy will discuss the  influence of emerging naval platforms and technologies in the geostrategic contours of the Indo-Pacific region. It identifies relevant historical precedents, forming the basis for various maritime development and security related projects in the region.

influence of emerging naval platforms and technologies in the geostrategic contours of the Indo-Pacific region. It identifies relevant historical precedents, forming the basis for various maritime development and security related projects in the region.

“Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.”– The Red Queen, Through the Looking Glass, Lewis Carroll.

By Vidya Sagar Reddy

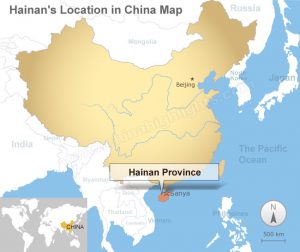

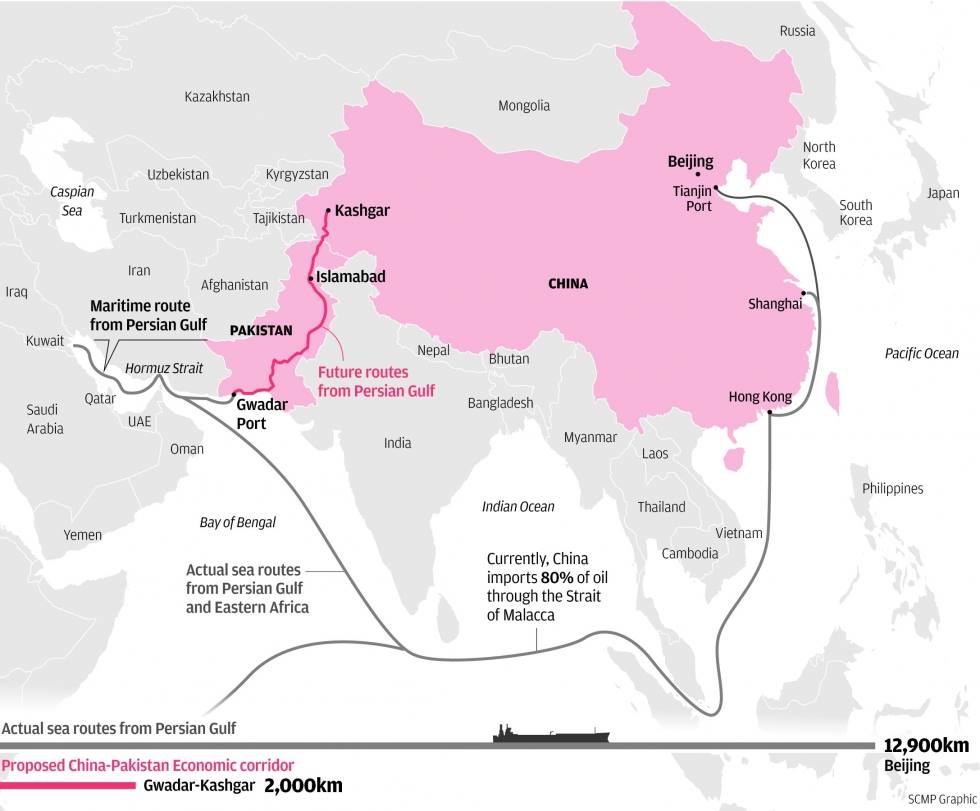

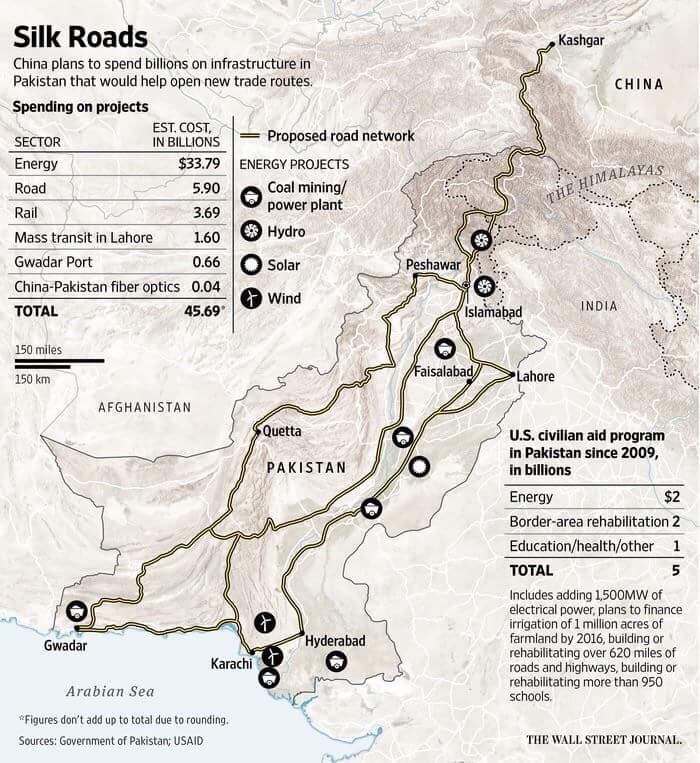

China has been pressing to complete the Gwadar port in Pakistan and build the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), allowing it to be connected over land to an Indian Ocean port. Gwadar and CPEC allow China to circumvent the Strait of Malacca which can be blockaded by rival navies in the event of conflict, termed as “Malacca Dilemma.” However, the rising activism of Balochistan independence parties could complicate these projects, compelling China to continue to depend on this Strait. This situation certainly bodes well for maintaining regional stability.

As China’s economic power burgeoned, its political class sought to transform the country into a major power by building comprehensive national power, which also requires investing in a sophisticated military. Political narratives were developed citing “historical” facts and figures to re-establish China’s position in the world order. However, China’s attitude towards its neighborhood has become increasingly assertive in recent years, signaling the rise of a potential regional hegemon. Those countries with stakes in maintaining the peace dividend responded by building alliances and partnerships to counter this security threat.

By signaling the intent to blockade the Strait of Malacca, these regional countries seek to deter China from military adventurism in the region. China’s economic growth is dependent on the seas, both for receiving energy and other raw materials required for low cost manufacturing, as well as the shipping of finished goods to markets in the U.S., Europe, etc. These ships have to pass through the Strait of Malacca situated between Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia connecting the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

Therefore a blockade of this Strait will impose energy and trade crises in China that can trickle down to hurt society, and in turn lead to pressure on the political class. Losing the people’s support will undermine the legitimacy of the Communist Party of China and could lead to an internal political transition. In fact, China’s history shows such transitions occurring after wars.

India has established credible naval presence in the Andaman Sea adjacent to the Strait of Malacca and is partnering with the U.S. and other countries in safeguarding it. Such presence can be translated into a formidable blockade. On the other hand, China has yet to showcase its capabilities and willingness to fight to keep this Strait open for its ships. Citing these developments, Hu Jintao termed this situation “Malacca Dilemma.”

His successor Xi Jinping resolved to overcome this dilemma by investing in the One Belt, One Road initiative. China moved determinedly to build ports in the Indian Ocean countries Myanmar, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Maldives. The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has been transformed into a blue water navy and is routinely deployed in the Indian Ocean. The docking of PLAN ships and submarines in Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and elsewhere in the region signals China’s intent to safeguard its energy and trade shipments in the Indian Ocean.

The ports in Myanmar and Pakistan have the added advantage of being connected to China via overland routes. This sea/land interspersed connectivity allows China to minimize maritime threats by rerouting its energy and trade over the land. During a conflict, China can focus its forward deployed naval assets f in the Indian Ocean on safeguarding the sea lines of communication connected to its ports in Pakistan and Myanmar instead of stretching those assets across the Ocean. The development of overland routes also serves Beijing’s intention to develop poorer western regions of the country.

China’s projects in Myanmar are proceeding with difficulties, with some of them cancelled due to opposition from local communities and environmental groups. Furthermore, China’s ships have to navigate the Bay of Bengal to reach Myanmar’s port which gives opportunity for rival navies to interdict. More significantly, Myanmar has recently undergone political transition from military rule to a democratically elected government. This transition signaled the country’s willingness to break through international isolation and normalize diplomatic relations with the outside world. As a result, China lost Myanmar as a client state and can expect a review of its projects as the new government balances between competing political and economic narratives in the region.

The trump card for China remains to be Pakistan. Despite international condemnation and American displeasure for its unwillingness to cease state sponsored terrorism, Pakistan continues to enjoy diplomatic leverage with the U.S., and despite the show of political clout in Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Maldives, India is still lacking a credible strategy to curtail Pakistan’s destabilizing behavior in the region.

China has adopted the earlier U.S. policy of hyphenating India with Pakistan and is willing to safeguard its client state’s interests across international forums. It has promised to invest $46 billion in Pakistan to complete the CPEC project. In addition, China is building nuclear plants, co-producing military jets, and will sell eight submarines; all incentives for Pakistan to align its interests with China’s.

In return, China will gain access to the Arabian Sea in the Indian Ocean, which is connected to the Persian Gulf, through the Gwadar port. The CPEC envisions building the requisite land route from Gwadar to China via the sensitive Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and Karakoram mountains, ignoring India’s apprehensions regarding building infrastructure in the disputed territories without consultations.

However, Pakistan itself is not without problems. The Balochistan province where Gwadar is located forms a major part of Pakistan’s territory and is highly rich in natural resources. However, its development needs have long been ignored by Islamabad. The Baloch people argue that neither the Gwadar port will benefit them but can instead lead to further exploitation of the province’s natural resources and affect their livelihoods.

India is convinced that the Gwadar port and the CPEC projects have underlying strategic intentions while the Baloch people question the veracity of economic benefits that can be derived from these projects to their province. Both parties are concerned about infrastructure build up in those areas considered sensitive for historical or strategic reasons. In this situation, Modi’s reference to Balochistan in his recent Independence Day speech signals India’s willingness to work with the Baloch people to confront the common problem and fulfil mutual interests.

While more details are pending, China is apparently concerned with these developments as its options to connect to the Indian Ocean via land routes fall into jeopardy, forcing continued reliance on the Strait of Malacca. This could be a welcomed development for upholding regional stability as it offers concerned countries an opportunity to maintain strategic deterrence and escalation dominance against China by controlling access to the Strait of Malacca.

Vidya Sagar Reddy is a research assistant in the Nuclear and Space Policy Initiative of the Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi.

Featured Image: Crew members work on the Chinese Navy ship Wei Fang as it docks in Myanmar on the outskirts of Yangon on May 23, 2014 (AFP 2016/ SOE THAN WIN)