First Prize Winner, 2015 CIMSEC High School Essay Contest

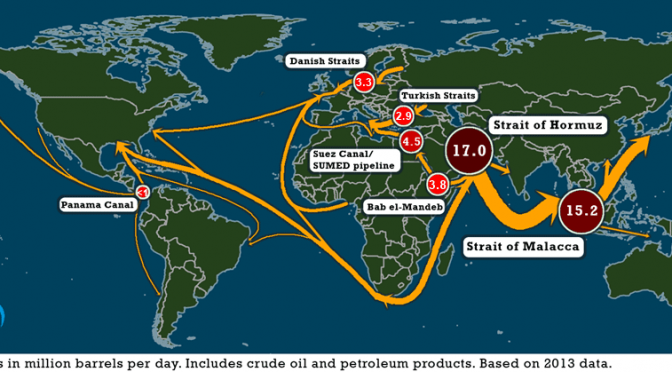

The nations of Somalia, Eritrea, Djibouti, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore all share a unique strength. Despite being third world countries and overall economically weak, they have strength in their geographic position; each are located on crucial waterways. These waterways consist of some of the most heavily traveled commercial shipping routes in the world. In terms of crude oil alone, the strait of Malacca in Southeast Asia has an estimated 15 million barrels a day, while the strait of Hormuz that links the Arabian Gulf to the Indian Ocean has an even larger amount of oil cargo, estimated at 17 million barrels per day.

These numbers are increasing exponentially every year as the global economy grows and becomes even more interconnected. Yet, despite their critical importance, these sea lanes are among the greatest hotspots for modernday piracy; a “movement” that costs the commercial shipping industry more than 16 billion dollars each year.

Maritime piracy is a global issue, and in these two regions, there is a trio of factors which have catalyzed the problem; weak economic opportunities for the local populations, a lack of security/enforcement by officials, and the geographic locations all provide ample opportunity for piracy. All of these factors are pretty apparent, and if you eliminate any of these three, you will see piracy decrease tremendously; the result is improved safety, perception, and ultimately, the profitability of the shipping industry.

The solution for the first decade of the 21st century has been to increase security. Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand have joined together to eliminate piracy in Southeast Asia and create safer shipping lanes. In the Red Sea, along the coast of Africa, and off the Arabian peninsula, western countries have taken

the initiative in eliminating piracy through the creation of the combined Maritime Forces; a collaboration of 26 countries and three task forces; CTF150 with Maritime Security & Counterterrorism, CTF151 with Counter-piracy, and CTF-152 with Persian Gulf Security Cooperation. Due to these efforts, attacks from piracy are at a record low and the seas are safer.

Piracy is a cyclical event that features both periods of outbreaks and minimal incidents. Currently, maritime piracy is under control, however it’s only a matter of time until the next wave of attacks. Following uneventful years, governments and shipping companies will become complacent due to this lack of incidents; they will assess the security threat and adjust their budgets. As companies and governments downsize their security investments, they allow the reinstatement of the one factor that they had eliminated; lack of law enforcement. As a result, pirate attacks will once again revamp.

In order to prevent another wave of attacks, a solution must be selected from a multitude of options. The first such solution would be the proven and traditional method of continued security forces/measures in high-risk locations. However, aside from being expensive, it is not permanent and places the burden of responsibility on Western governments. A spinoff of this idea, and an emerging method, is to place this burden on the shipping companies themselves and have them invest in their own security measures. This capitalistic approach expands the market for private security firms. However, in pursuit of profits, shipping companies might try to cut corners. This would allow for increased attacks, which almost always escalate into hostage situations that have to be dealt with through military intervention.

In order to prevent another wave of attacks, a solution must be selected from a multitude of options. The first such solution would be the proven and traditional method of continued security forces/measures in high-risk locations. However, aside from being expensive, it is not permanent and places the burden of responsibility on Western governments. A spinoff of this idea, and an emerging method, is to place this burden on the shipping companies themselves and have them invest in their own security measures. This capitalistic approach expands the market for private security firms. However, in pursuit of profits, shipping companies might try to cut corners. This would allow for increased attacks, which almost always escalate into hostage situations that have to be dealt with through military intervention.

Taking a more permanent approach to fixing the problem is to address a different factor: poor economic conditions. This could be done through direct investment into a region’s economic development or into developing local security forces. To take the direct investment approach would be a long-term approach that would benefit the country overall. Developing local security forces, for example matching dollar for dollar, would be an intermediate solution that would both create economic opportunity while placing the burden of security on local governments. This second approach would be arguably the best in countries such as Indonesia and Singapore because they are already investing in securing their waterways. However, neither of these approaches are applicable in countries with corrupt or unstable governments, particularly Somalia where there’s no central government and various Warlords are in control.

The most unique approach to piracy would be unmanned or drone ships. As the name implies, they would operate similar to U.S. military drones where a controller sits in a building thousands of miles away, while a satellite link provides the controller with the ability to control the craft while receiving input from visual and other sensors. This is a newly emerging concept; in February of 2014, Rolls Royce announced they are developing drone cargo ships, and in November of 2014, Space X unveiled a drone barge for their reusable rocket program. In terms of freighting, the benefits range from better energy efficiency to lower cost due to the lack of a crew.

Drone ships are not pirate proof; they could still be hypothetically hijacked depending on the design of the ships. An example would be that if the engine systems were not secured/contained enough, the vessels propulsion could be halted. The reason drone ships would be so effective against piracy is they eliminate the worst situation for security forces to combat; hostage situations.

The creation of drone ships are host to numerous other difficulties; as with any form of creative destruction that causes structural unemployment, the idea will be, and already is opposed by many who make their livelihood aboard ships. Additionally, unmanned ships are currently illegal under international conventions that set minimum crew requirements. Even if that hurdle was to be overcome, then regulations would still have to be created for the new ships.

So which of the options would be the most effective? A combination of all the different methods would probably be the best solution in both the short and long run. No matter what solution is best, governments and companies need to choose a method and instate it in the coming years to ensure we don’t see another wave of attacks. Growth of the world’s economy depends on the safety of the major waterways, and inaction could cost lives.

Citations

Kermeliotis, Teo. “Somali Pirates Cost Global Economy ‘$18 Billion a Year’.” Piracy on the High Seas. Ed. Debra A. Miller. Farmington Hills, MI: Greenhaven Press, 2014. At Issue. Rpt. from “Somali Pirates Cost Global Economy ‘$18 Billion a Year.’.” CNN.com. 2013. Opposing Viewpoints in Context. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Debusmann, Bernd. “Military Action and Foreign Aid Must Be Used to Eliminate Pirate Sanctuaries.” ModernDay Piracy. Ed. Debra A. Miller. Detroit: Greenhaven Press, 2012.

Current Controversies. Rpt. from “Why High Seas Piracy Is Here to Stay.” Reuters 4 Mar. Opposing Viewpoints in Context. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Arnsdorf, By. “RollsRoyce Drone Ships Challenge $375 Billion Industry: Freight.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 25 Feb. 2014. Web. 13 Jan. 2015. .

“Combined Maritime Forces.” Combined Maritime Forces. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Smith, Mat. “SpaceX Is Going to Land a Rocket on a ‘spaceport’ Barge.” Engadget. 17 Dec. Web.13Jan.2015. <http://www.engadget.com/2014/12/17/spacexrocketlandingxwingsupersonicautonomous spaceportdroneship>

“U.S. Energy Information Administration EIA Independent Statistics and Analysis.” World Oil Transit Chokepoints Critical to Global Energy Security. EIA, 1 Dec. 2014. Web. 13 Jan. 2015 <http://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.cfm?id=18991>

About the Author

Steel Templin is a senior from South Lake High School in Groveland, Florida. He is active in Key Club, Student Government, and National Honor Society, and holds leadership positions in each. In addition to school clubs, he is a varsity football player and varsity crew member. Steel hopes to attend and row at either the Naval Academy, Cornell, or Georgia Tech and study nuclear or aerospace engineering. Additionally, after college Steel plans to serve in the military or one of our country’s security agencies.

This February, the Shakespeare Theatre Company (STC) is bringing the National Theatre of Scotland’s production of David Greig’s Dunsinane to the nation’s capital. The STC’s Young Professionals Consortium, in partnership with The Strategy Bridge and the Center for International Maritime Security, has organized #Shakespeare and Strategy, a special online seminar to accompany this exciting play.

This February, the Shakespeare Theatre Company (STC) is bringing the National Theatre of Scotland’s production of David Greig’s Dunsinane to the nation’s capital. The STC’s Young Professionals Consortium, in partnership with The Strategy Bridge and the Center for International Maritime Security, has organized #Shakespeare and Strategy, a special online seminar to accompany this exciting play.

approach was taken thus far is to use large surface combatants such as frigates and destroyers as escorts for merchant ships as well as touring African nations and training their respective navies in counter-piracy operations. These measures, when combined with better safety measures taken by commercial vessels, have been extremely effective since 2012 and attacks off Somalia have become almost vanishingly rare at this point in time.1 This being said, these measures are fairly expensive both in money and in combat forces and while the threat off the Horn of Africa has been put into remission temporarily, the underlying issues that lead to the growth of piracy in the region remain.2 Thus if the governments responsible for this crackdown on piracy wish to continue to suppress piracy without devoting significant monetary resources and a handful of large surface combatants to the region a change in strategy is required.

approach was taken thus far is to use large surface combatants such as frigates and destroyers as escorts for merchant ships as well as touring African nations and training their respective navies in counter-piracy operations. These measures, when combined with better safety measures taken by commercial vessels, have been extremely effective since 2012 and attacks off Somalia have become almost vanishingly rare at this point in time.1 This being said, these measures are fairly expensive both in money and in combat forces and while the threat off the Horn of Africa has been put into remission temporarily, the underlying issues that lead to the growth of piracy in the region remain.2 Thus if the governments responsible for this crackdown on piracy wish to continue to suppress piracy without devoting significant monetary resources and a handful of large surface combatants to the region a change in strategy is required.

In order to prevent another wave of attacks, a solution must be selected from a multitude of options. The first such solution would be the proven and traditional method of continued security forces/measures in high-risk locations. However, aside from being expensive, it is not permanent and places the burden of responsibility on Western governments. A spinoff of this idea, and an emerging method, is to place this burden on the shipping companies themselves and have them invest in their own security measures. This capitalistic approach expands the market for private security firms. However, in pursuit of profits, shipping companies might try to cut corners. This would allow for increased attacks, which almost always escalate into hostage situations that have to be dealt with through military intervention.

In order to prevent another wave of attacks, a solution must be selected from a multitude of options. The first such solution would be the proven and traditional method of continued security forces/measures in high-risk locations. However, aside from being expensive, it is not permanent and places the burden of responsibility on Western governments. A spinoff of this idea, and an emerging method, is to place this burden on the shipping companies themselves and have them invest in their own security measures. This capitalistic approach expands the market for private security firms. However, in pursuit of profits, shipping companies might try to cut corners. This would allow for increased attacks, which almost always escalate into hostage situations that have to be dealt with through military intervention.