By Ching Chang

This article aims to provide a fair assessment of the military significance of the South China Sea land features. The term land feature is intentionally selected to avoid the trouble of arguing whether they are islands, reefs, shoals or rocks. How these land features can be categorized into the terms shown above may possibly cause differences according to the international regimes governing maritime jurisdictions, but not the military significance of the land features alone. Whether these land features may contain military value significant enough to be fought for are never decided by themselves. Other factors such as force, timing and additional characteristics associated with the space will fundamentally define their importance.

The space factor itself may only decide part of the operational conditions for any potential military campaign. Land features within the maritime theater should be assessed together with surrounding waters in the military geographical calculus. Hence, the land features, particularly within the maritime battlespace, are only a portion of geographical variables in the strategic and operational formulas for employing military forces. For the case of the South China Sea, the author would like to present the following points to remind strategic thinkers, political commentators, and military observers never to overstate, or even to overrate, the military significance of the land features in the South China Sea.

It is well proven by history that the land features in the South China Sea are fundamentally irrelevant with the generally perceived freedom of navigation, either in wartime or in relative peacetime. The United States Navy deployed submarine forces to target Japanese shipments in World War Two. Several engagements did occur in the South China Sea though no significant achievement was derived through these efforts.1 Nonetheless, it is pretty sure the land features had no influence on submarine blockade operations for either side.

Further, Operation Pocket Money launched by United States Navy Task Force 77 on May 9, 1972 during the Vietnam war for a naval mining mission was also irrelevant to those land features in the South China Sea, either.2 For these two obvious cases of paralyzing freedom of navigation around the South China Sea, those land features had no relevance within these operations. Only maritime assets, sometimes including air superiority, really mattered in operations aimed at hindering freedom of navigation.

Moreover, there are two maritime campaigns in the last half of the previous century specifically targeted on acquiring these land features. The first was the Battle of the Paracel Islands that occurred on January 19, 1974 between the naval forces of the People’s Republic of China and their maritime adversaries of the Republic of Vietnam Navy. It was originally a battle triggered by the effort of the South Vietnamese Navy to oust the Communist China’s naval vessels in the vicinity of the Paracel Islands. China successfully secured permanent control over the Crescent Group of the Paracel Islands after defeating Vietnamese maritime forces.

The second case was the 1988 Johnson South Reef Skirmish between the People’s Liberation Army Navy forces and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam Navy vessels. This naval battle took place over Johnson South Reef in the Spratly Islands on 14 March, 1988. China established its active presence around the Spratly Islands right after the decisive victory from a less than thirty-minute maritime engagement. By the end of 1988, China held six footholds on the land features in the Spratly Islands. The important lesson is that freedom of navigation in the South China Sea was never affected by these two naval campaigns specifically targeted on obtaining islands but fought with naval vessels to exclude adversary’s maritime presence around these land features.

From the two directions of logic reasoning shown above, the naval operations actually affected the freedom of navigation were irrelevant with the land features within the South China Sea. On the other hand, the naval campaigns for acquiring the land features within the South China Sea by expelling the adversary’s maritime presence around these land features were never relevant to the freedom of navigation, particularly, the maritime commercial transportation in the South China Sea. It only affected the maritime force within the surrounding waters of these land features. Why the territorial disputes fundamentally realized by the land features are so relevant to the freedom of navigation can be well perceived by measuring their locations subsequently introduced by the following second point.

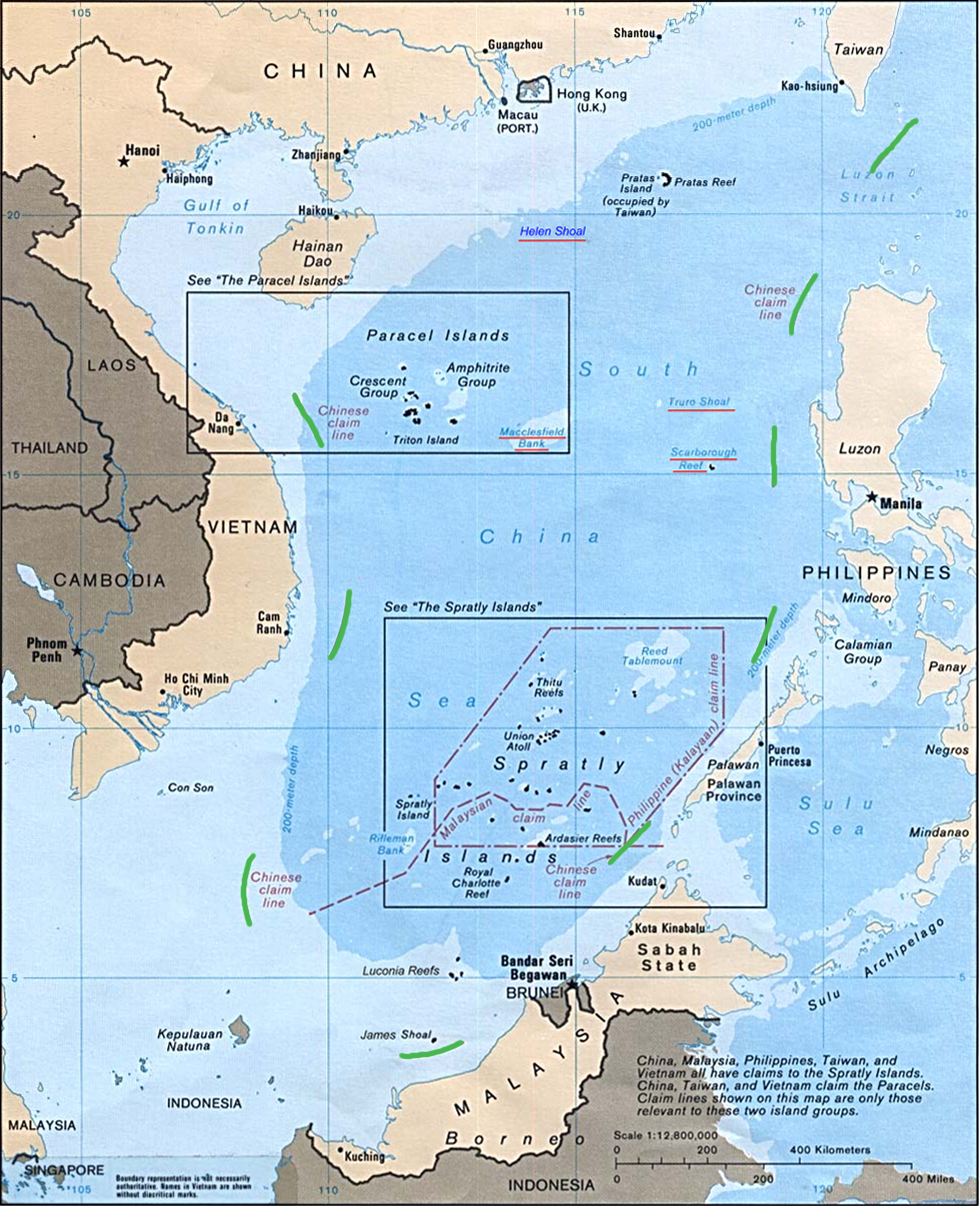

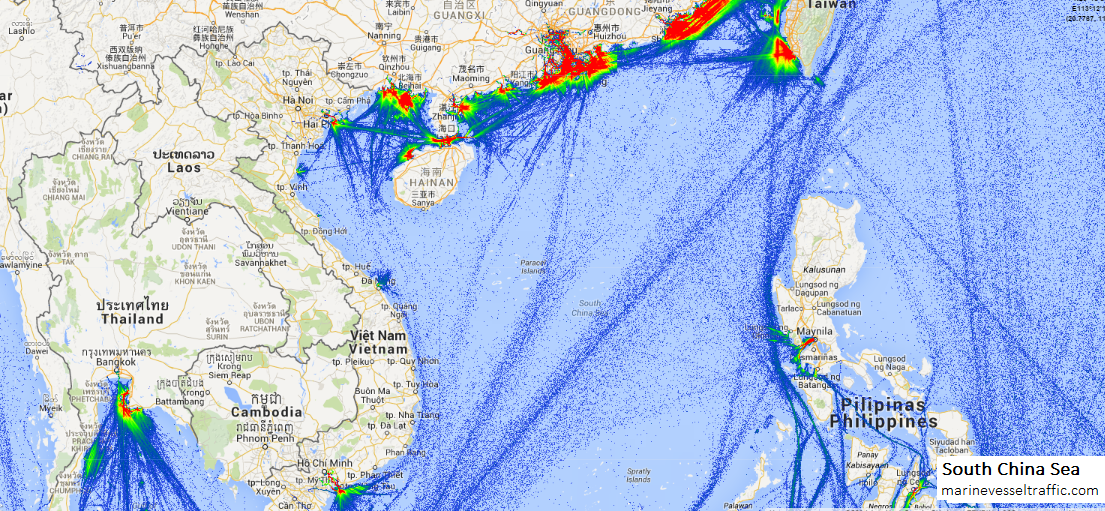

The locations of these land features are away from major sea lines of communication as shown by the picture below.

We may therefore understand why these land features may not affect freedom of navigation since most maritime commercial transportation is quite distant from these disputed land features. Even land features that may be potential hot spots and could influence maritime campaigns to some extent are hardly a factor in hindering maritime transportation activities on a significant scale. In terms of a maritime campaign in the South China Sea, maritime platforms and air superiority really matter, not these land features.

Some may argue that land-based weapons such as anti-ship missiles may substantially hinder freedom of navigation. Again, the prerequisites of this engagement scenario are maritime transportation activities close enough to these land features. Certain military assets can exercise the sea control function, but never the land features themselves. Without the maritime reconnaissance supporting functions to match with the weapon systems, those land based anti-ship missiles are nothing but a fist with long reach but poor aim.

No one within the military chain of command dare shoot at any long range target at sea so blindly without achieving fully identification. Any case similar to the RMS Lusitania sunk by a German submarine on May 7, 1915 will present a nightmare to military and political decision makers.

W need to scrutinize the relative geographical locations of these land features. Basically, these land features are occupied by various parties and are all tangled together. For any individual land feature, regardless of its size and characteristics, it can only be defined as an isolated spot or foothold. Given the distances among these land features occupied by any single claimant in the South China Sea, it is impossible to form any meaningful defense. As no firepower from any other individual land feature may substantially cover the surrounding waters of other land features held by the friendly force units, the overall defensive posture is fragmented. No organized military operations seem feasible in the environment with the layout of land features as such. No meaningful military front or defensive zone can be possibly established in this operational space.

All the land features cannot mutually support each other all since the effective range of land-based firepower may not match with the distances between these land features. Without maritime surveillance capability, long range anti-ship missiles may not be operationally relevant in many engagement scenarios. Given the historical experience of the island hopping operational concept successfully employed in the Pacific theater in WWII, these land features can be easily bypassed because they cannot control any sea lane of communication. In other words, these land features can be ignored in any significant maritime campaign since they cannot form any organized military front or defense zone to support orchestrated military maneuvers.

It is reasonably expected that some may challenge this perspective with the recent developments and construction work occurring on these land features. It is undeniable that the capabilities of each land feature will be significantly enhanced after these improvements are completed. Accompanied with these enhanced capabilities, the logistical loads will also be increased. Although the strategic value of these land features would be seemingly increased, yet, the fundamental question remains the same: whether occupants of these land features may enact any meaningful military operations from these facilities including harbors, runways, berthing sites, and helicopter pads. Again, it will be decided by the distance between these land features and those frequently used maritime transportation routes. Enhancing military capabilities serving no substantial military tasks but only adding logistical burdens may make the land features a “strategic appendix” offering little utility but containing risk.

Last but not least, to answer the fundamental question of the military significance of the South China Sea land features, the question should be “what military operations in this maritime theater would rely on these land features?” Unquestionably, holding these land features may provide certain political leverage for claiming maritime jurisdiction upon adjacent waters. Nonetheless, fortification of these land features will not enhance existing positions on territorial claims, nor military significance for conducting potential operations. Facilities on these land features for supporting force employment and maritime surveillance will not be the most essential elements of any future military contingency within this maritime theater. Maritime assets will still be the core element. These land features can only serve a relatively minor role in a maritime campaign in the South China Sea as they always have in the past.

Chang Ching is a Research Fellow with the Society for Strategic Studies, Republic of China. The views expressed in this article are his own.

Endnotes

1. Heden, Karl E., Sunken Ships World War Two, Branden Books, 2006.

2. Mining of Haiphong Harbor, VietnamWar.net, http://www.vietnamwar.net/HaiphongHarbor.htm

Featured Image: China’s new airstrip built over Fiery Cross Reef in the South China Sea (CSIS image)