By Ryan D. Martinson

Chinese leaders, like leaders elsewhere, rely on the advice of outside experts—academics and other professional scholars—to help them cope with the myriad challenges of international politics. Statesmen and scholars, however, come from very different worlds. When leaders craft foreign policy, they place a premium on secrecy. Scholars, by contrast, have powerful motives to share their views and tout their influence.

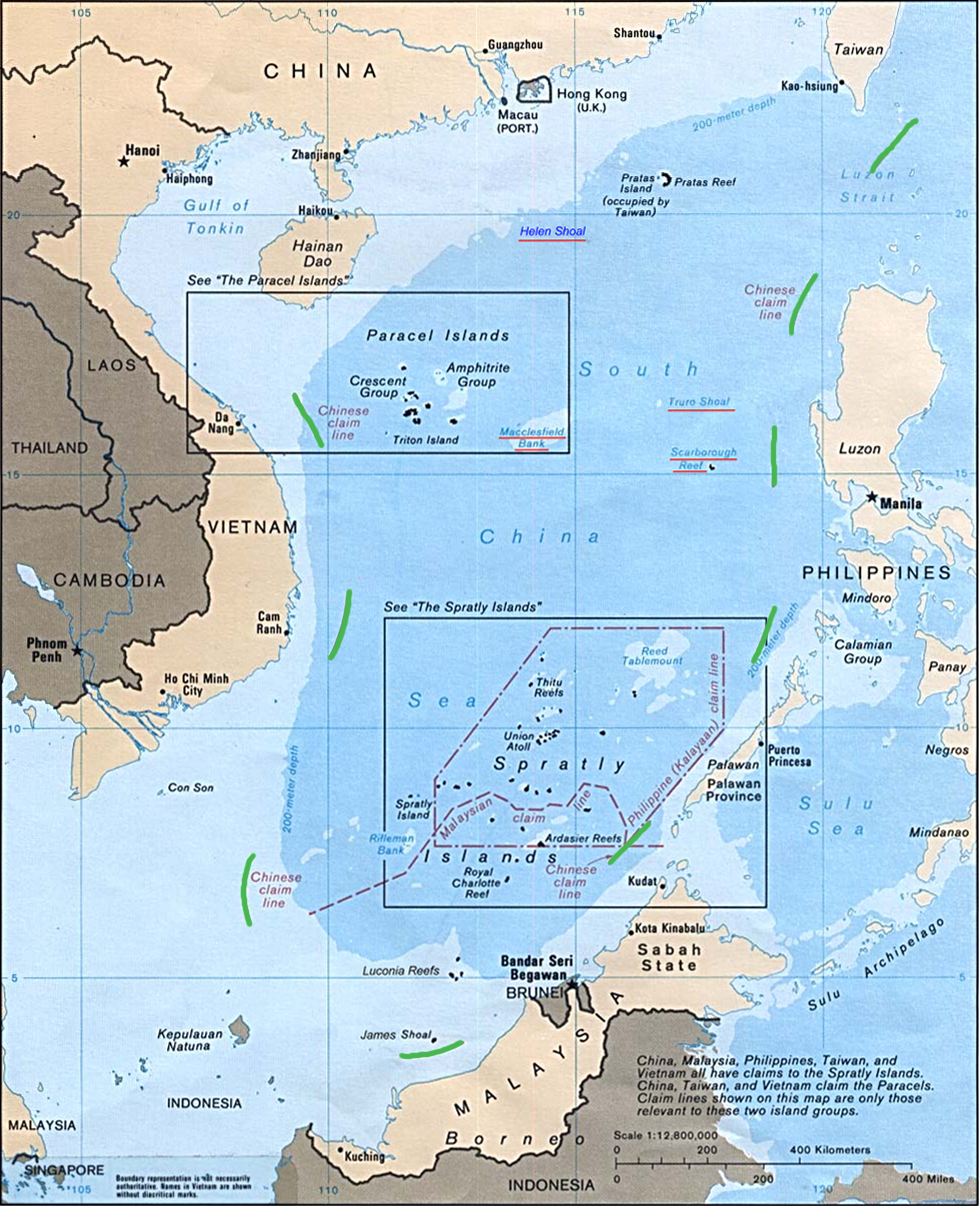

For those studying an opaque state like the People’s Republic of China (PRC), it is therefore very tempting to regard the “influential” Chinese scholar, who writes and speaks without reserve, as a proxy for the shy statesman he serves. The lure of this approach is especially strong in the case of the South China Sea, where authoritative—and reliable—statements of PRC intentions are particularly scarce. In the aftermath of the recent ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (Case No. 2013-19), the writings of Chinese scholars will no doubt be closely scrutinized for insights about the PRC’s likely response to this desolating blow to its South China Sea claims.

But is this a wise approach?

We must immediately distinguish the advisor from the propagandist. Both have direct connections with the state. Indeed, an individual scholar may serve both functions. As a propagandist, the scholar justifies past and current policy; as an advisor, she seeks to shape future policy. Studying the work of the propagandist has merits: we learn what the PRC wants domestic and international audiences to believe. The statements of the advisor, however, are potentially much more rewarding, for they may suggest future actions. Knowing what a state may do allows one to engage in proactive diplomacy and prepare countermeasures.

Given the legal and strategic complexities of the issues at stake, Chinese scholars have an important advisory role to play in South China Sea policy. However, among the dozens (hundreds?) of Chinese scholars researching the law and politics of the South China Sea, the vast majority will never speak to or have their work read by men and women in positions of real authority. Thus, if one’s aim is to conjecture about the direction of PRC policy, the works of only a tiny number of Chinese scholars—i.e., those with demonstrable influence—are worth considering.

Researchers at the Hainan Center for South China Sea Policy and Law (海南省南海政策与法律研究中心) fall into this category. Examining this institute—and the work of one scholar in particular—allows us to explore what can and cannot be learned from the writings of “influential” Chinese scholars.

Established in December 2011, the Center is based at the Hainan University School of Law. Its mission is to “research the law of the South China Sea and serve national strategy.” It employs 17 full-time and 15 part-time researchers, all studying issues directly and indirectly related to China’s position in the South China Sea.

The Center is very closely connected to the Chinese government. Indeed, the chair of its academic committee is Gao Zhiguo, who directs a major research unit located within the State Oceanic Administration (SOA). Gao lectures widely on maritime issues, his audiences ranging from small communities of specialists to the most senior members of the Chinese party-state. In sum, the Center is a large, well-connected institute that exists to find answers to the most important questions facing Chinese policy in the South China Sea.

Like all academic institutions, the Center seeks to publicize the achievements of its resident experts. To this end, it posts detailed data about the research grants it receives. As of October 2015, the Center had been awarded dozens of grants totaling millions of RMB from entities such as the National Planning Office of Philosophy and Social Science (NPOPSS), the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Justice, and the Hainan provincial government.

Such information is valuable in and of itself. Project names and grant amounts suggest which topics are important to the Chinese government. Since 2012, for example, Center researcher Wang Chongmin received half a million RMB (~$75,000) from SOA in order to do preliminary work on a “maritime basic law,” a comprehensive statement of China’s maritime claims and the roles and responsibilities of state entities charged with defending them. In 2015, Center researcher Chen Yangle was awarded 200,000 RMB (~$30,000) from NPOPSS to examine how China might promote tourism to the disputed Spratly Islands without undermining the “Maritime Silk Road” initiative, a policy aimed at cultivating regional good will. Since 2012, Chen Qiuyun received 50,000 RMB (~$7,500) from the Ministry of Justice to study how sailing directions (更路簿) supposedly handed down by generations of Chinese fishermen might bolster the legitimacy of PRC claims.

Center researcher Zou Ligang is a special case. From 2010-2012, NPOPSS awarded Zou a total of 120,000 RMB (~$18,000) to complete a project entitled “Research on Legal Issues Associated with the South China Sea Problem and a Program to Resolve It.” This bland title might be easily overlooked, were it not for the fact that NPOPSS appraised Zou’s work as “outstanding”—an honor the Center was eager to promote. Indeed, a closer examination of this project reveals a direct connection between Zou and the highest levels of the Chinese government.

As luck would have it, the Hainan Society of Social Sciences published a lengthy synopsis of Zou’s project. His overall objective was to probe China’s existing South China Sea policy and suggest improvements. One particular focus was the “nine-dashed line,” the undefined cartographical monstrosity that continues to confuse and dismay the coastal states of Southeast Asia. Zou proceeds from the assumption China has “jurisdiction” over all of the two million square kilometers of maritime space within the nine-dashed line. The purpose of his research was to create a legal basis for China to “control” (管控) these waters, and to do so without seriously harming regional stability.

The synopsis outlines Zou’s policy recommendations. Most reflect conventional thinking. For example, China should build and better coordinate its navy, coast guard, and maritime militia and leverage these capabilities in order to increase “routine administrative control” over Chinese-claimed waters. Zou also proposes that China revamp its domestic maritime law—again, a point that many other Chinese experts have been making for years. Other recommendations are less expected. These include taking steps to reduce the Chinese economy’s dependence on foreign powers and paying due regard to the interests of extra-regional powers (such as the U.S.) in the South China Sea.

The synopsis also sketches Zou’s conclusions about the “legal status” of the nine-dashed line. Zou admits that within China there exists no consensus on this question. However, since the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is based on the principle that “the land dominates the sea,” Zou concludes that China’s maritime boundaries in the South China Sea should be largely determined by Chinese-claimed islands and other features. However, Zou asserts, this principle should not “impede China from claiming historic rights to certain specified waters within the nine-dashed line.” Taken together, Zou seems to be recommending that China use UNCLOS to claim as much space within the nine-dashed line as possible, and then use another argument based on “historic rights” to buttress Chinese claims to the remaining space.

If, as Zou suggests, offshore islands should largely determine China’s maritime rights in the South China Sea, the approach China adopts to draw baselines around these islands takes on tremendous importance. Zou has much to say on this topic. While China was correct to draw straight baselines around all of the Chinese-controlled Paracel Islands, this method would not work for the Spratlys because they are too widely dispersed. Thus, Zou recommends using the same approach that China applied to the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea. That is, China should draw baselines around different clusters of features within the archipelago, with zones of sovereignty and jurisdiction extending from them. The synopsis does not say which. However, in a 2013 journal article published under this grant number, Zou recommends that China center these clusters on Itu Aba (currently occupied by Taiwan), Thitu Island (the Philippines), West York Island (the Philippines), Spratly Island (Vietnam), and Mischief Reef (China).

Zou’s project was not funded for the sake of truth and knowledge. Its findings were intended to serve as a resource for policymakers. The synopsis states that, aside from journal articles like the one cited above, Zou also produced (or helped produce) 26 research reports for internal consumption. Among these reports, 10 were directly “adopted” by Hainan province, which administers all Chinese-claimed waters in the South China Sea (we do not learn which 10). Even more important, some of Zou’s reports landed on the desks of national Party officials. Three in fact were read and approved with comment (批示) by Xi Jinping and other members of the Politburo. The synopsis cites their titles: 1) “Views on Certain Issues Related to Maritime Law,” 2) “Legal Thinking with Respect to Resolving the Maritime Disputes,” and 3) “Strategic Research on Building the Maritime Silk Road.”

To sum up, we have learned that the Hainan Center for South China Sea Policy and Law is a major research institute producing policy-relevant analysis on the South China Sea for the direct benefit of the Chinese government at both the provincial and national levels. We know the names of individual projects and have the means to track down journal articles produced under specific grant numbers. In the particular case of Zou Ligang, we know that several of his reports were read and approved by the Politburo during a period of great flux in Chinese foreign policy. By reading articles published under this grant number, we can speculate about the advice Zou and his colleagues directly provided China’s most important decision makers.

We might ask, would knowledge of Zou’s proposals have enabled a foreign analyst to anticipate Chinese actions in the 2-3 years since they were submitted? That is, given Zou’s demonstrated advisory role on South China Sea issues, would it have been wise to regard his work as a portent of Chinese policy to come?

To be sure, China has pursued some of the policies recommended in Zou’s reports. It has invested heavily in its navy, coast guard, and militia. It has sought to enhance its control over claimed land and sea. In pushing forward with the drafting of a maritime basic law, it has taken steps to improve the maritime legal regime. However, these proposals reflect mainstream thinking in China. At most, then, Zou merely endorsed the existing consensus.

The legal status of the Spratly Islands, a much debated topic in China, is a more interesting test case. It is still too early to know for sure how China will draw baselines in the Spratlys. However, a recent article published in the PLA Daily under the byline of a research institute within the Central Party School suggests that China could ultimately settle on an approach that approximates Zou’s proposal. The article says that the “most likely and most appropriate” method for drawing baselines in the Spratlys is that used for the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands. Such an approach, the article goes on, would center baselines around Itu Aba, Thitu Island, West York Island, Spratly Island, and Mischief Reef—the very same features recommended by Zou. If China does ultimately take this path, it is very possible that Zou Ligang will have played a significant role in this decision.

Still, one must acknowledge the limits of this approach. If one had relied on Zou’s work as a guide to future Chinese policy one would fail to foresee by far the most provocative Chinese action in recent memory: the conversion of tiny Spratly outposts into major military bases. Zou proposed policies that he believed would allow China to realize its aims without destabilizing the region. In choosing to construct new Spratly facilities, PRC leaders are plainly operating on an entirely different set of assumptions.

Thus, even when we are certain that a particular expert has the ear of Chinese leaders, we cannot know which proposals—if any—will ultimately be adopted. On any single issue, Chinese leaders no doubt consult a number of scholars. It is impossible to know whose ideas will have purchase. Moreover, outside academics are not the only source of ideas influencing Chinese policy. Experts employed directly by the state (and writing mostly or entirely for internal audiences) may convince Chinese leaders they have a better grasp of the issues at stake. Ultimately, facts and logic may not even be decisive: domestic politics or intangible factors like “national dignity” might trump expertise.

In conclusion, analyzing the work of “influential” Chinese scholars may help gauge the trajectory of Chinese policy in the South China Sea. This approach is bound to be most fruitful when the products of specific research projects can be directly linked to PRC decision makers. In such cases, policy recommendations may reflect actual policy options under consideration by those in positions of power. However, one must recognize that Chinese academics represent only one source of ideas. By fixating on the work of the scholars, we risk exaggerating their influence. Indeed, too much emphasis on this single source may go a long way to explain the failure of the American China studies community to foresee recent PRC actions—above all, the decision to build the new Spratly facilities that have so dramatically altered the regional balance of power.

Ryan D. Martinson is a researcher in the China Maritime Studies Institute at the U.S. Naval War College. The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Navy, Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Featured Image: National Institute for South China Sea Studies (NISCSS)

“…. While China was correct to draw straight baselines around all of the Chinese-controlled Paracel Islands…”

I beg to disagree with that assessment.

UNCLOS Article 47 allows such straight baselines only for an ARCHIPELAGIC state.

Even China has never advanced such an absurd proposition [UNCLOS Article 46 clearly sets out why China can never be an archipelagic state].

****

US State Department

“… regardless of sovereignty, straight baselines CANNOT be drawn in this area [Paracels]….” page 8

http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/57692.pdf