This is an article in our first “Non Navies” Series, written by Byron Ramirez and Dr. Robert J. Bunker

Drug cartels today are much more organized, adaptive, and strategic. Over time, they have acquired vast financial resources that allow them to invest in technologies geared towards providing them with a strategic edge. Drug cartels have learned to adapt to a changing environment where law enforcement authorities and militaries are also seeking to find their own effective ways of disrupting the flow of illicit drugs. Technology has become a source of competitive advantage and both drug cartels and militaries have been investing in engineering and technological tools that will allow them to counteract one another.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

On one side, drug cartels attempt to optimize their operational efficiency while mitigating the risk of detection, seizure, and capture. On the other side, we have law enforcement and militaries’ efforts to improve their surveillance and detection capabilities. This race to out-flank and counteract one another has led to the development of narco-submarines.

On one side, drug cartels attempt to optimize their operational efficiency while mitigating the risk of detection, seizure, and capture. On the other side, we have law enforcement and militaries’ efforts to improve their surveillance and detection capabilities. This race to out-flank and counteract one another has led to the development of narco-submarines.

During the past twenty years, Colombia’s various drug cartels have engaged in investing in and developing narco-submarine technology that will yield a competitive edge. Over time, their increasing need to evade capture and confiscation of narcotics led drug cartels to move away from using go-fast boats and planes, and instead turn towards developing in-house, homemade, custom built narco-submarines.

A narco-submarine (also called narco-sub) is a custom-made, self-propelled vessel built by drug traffickers to smuggle their goods. Over the years, their engineering, design and technology have improved, thus making them more difficult to detect and capture. Moreover, from a cost-benefit perspective, the yielded benefits are far superior to the associated costs of building these vessels.

Although militaries and law enforcement agencies have become progressively collaborative in their efforts to reduce the flows of narcotics, the use of narco-submarines enables narcotics to continue to reach their destinations while reducing the probability of detection. Albeit, there have been some confiscations of narco-submarine vessels over the last several years. These appropriations in turn have led to our understanding of how narco-submarines are designed, engineered, and used to deploy narcotics.

Cocaine smuggling from the Andean region of South America to the United States generates yearly revenues in the high tens of billions of dollars (e.g. 2008 UN estimate of USD $88 billion retail) and over the last thirty-five years has produced in the low trillions of dollars in retail sales. The use of narco-subs and related vessels represents one component of a broader illicit distribution strategy that also relies upon go-fast boats, airplanes, the hiding of narcotics inside bulk containers and smaller commodities, drug mules, and other techniques to covertly get this high value product into the U.S.

In fact, as of June 2012, maritime drug smuggling accounts for 80% of the total illicit flow from the Andean region into Honduras, Mexico and other mid-way transportation regions prior to entry into the U.S. About 30% of the maritime flow is estimated by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) to utilize narco submarines. Overall, however, maritime interdiction rates are very low. In March 2014, the commander of the U.S. Southern Command testified to Congress that:

“Last year, we had to cancel more than 200 very effective engagement activities and numerous multilateral exercises, Marine Corps Gen. John F. Kelly told members of the Senate Armed Services Committee. And because of asset shortfalls, Southcom is unable to pursue 74 percent of suspected maritime drug trafficking, the general said.

“I simply sit and watch it go by,” he continued. “And because of service cuts, I don’t expect to get any immediate relief, in terms of assets, to work with in this region of the world.”

As a result, it can be seen that narco-submarines and related maritime drug trafficking methods are being carried out with relative impunity, with only about 1 in 4 craft presently being interdicted.

Per the testimony of Rear Admiral Charles Michel, JIATF-South Director, in June 2012, the following statistics pertaining maritime contact numbers and interdictions are provided:

JIATF-South detected an SPSS [Self-Propelled Semi-Submersibles] at sea for the first time in 2006. By 2009, the interagency detected as many as 60 SPSS events were moving as much as 330 metric tons per year. Prior to 2011, SPSS had only been employed by traffickers in the Eastern Pacific. However, since July 2011, JIATF-South has supported the disruption of five SPSS vessels in the Western Caribbean, each carrying more than 6.5 metric tons of cocaine.

There have been a total of 214 documented SPSS events, but only 45 were disrupted due largely to the difficulty of detecting such low-profile vessels.

The numbers of these vessels which now exist is also highly debatable with potentially dozens of them being produced every year by criminal organizations in Colombia such as the FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia), Rastrojos, and Urabeños. One point greatly influencing the numbers of these vessels which exist at any specific time is if they are utilized once and then scuttled after their delivery (the traditional U.S. military viewpoint) or if they are utilized multiple times (the traditional Colombian military viewpoint). Depending on the perspective held, greater or lesser numbers of narco subs would be required to be produced each year to replenish the vessels lost due to capture, accidental sinking, intentional-scuttling to avoid capture, and, potentially most importantly, at the end of a delivery run.

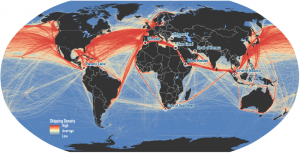

What is known is that the capability of these vessels has grown over the last two decades with their evolution and, if the Colombian cartels’ dream of making the journey (using fully submersible narco-subs) to West Africa and Europe is realized, such subs would very well represent a valuable cross Atlantic trafficking resource that would not likely be scuttled at the end of such a profitable illicit trade route.

Given this context concerning the immense values associated with the cocaine trade to the U.S. and the large amount of these illicit drugs not being interdicted during the initial leg in their journey to the United States, we have written a paper, “Narco-Submarines – Specially Fabricated Vessels Used For Drug Smuggling Purposes”, soon to be released by the Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) and intended to be an initial primer on the subject of narco-submarines, that is, those specially fabricated vessels utilized principally by Colombian narco traffickers and developed to smuggle cocaine into the U.S. illicit drug market.

This work is anticipated to appear in the Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) website as unclassified research conducted on defense and security issues that are understudied or under-considered. The work contains a preface written by Dr. James G. Stavridis, and a number of essays written by U.S. Navy Captain Mark F. Morris, Adam Elkus, Hannah Stone, Javier Guerrero Castro, and Byron Ramirez discussing and analyzing narco-submarines. The paper also comprises a comprehensive photo gallery, arranged in chronological order, which allows the reader to observe the evolution of narco-submarine technologies. It also contains a cost benefit analysis of using narco-submarines, as well as a map and a table that highlights where these distinct narco subs were interdicted. The data that we came across seems to propose that cartels have been using different types of narco-submarines concurrently; hence, they seem to be employing a mixed strategy.

This work is anticipated to appear in the Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) website as unclassified research conducted on defense and security issues that are understudied or under-considered. The work contains a preface written by Dr. James G. Stavridis, and a number of essays written by U.S. Navy Captain Mark F. Morris, Adam Elkus, Hannah Stone, Javier Guerrero Castro, and Byron Ramirez discussing and analyzing narco-submarines. The paper also comprises a comprehensive photo gallery, arranged in chronological order, which allows the reader to observe the evolution of narco-submarine technologies. It also contains a cost benefit analysis of using narco-submarines, as well as a map and a table that highlights where these distinct narco subs were interdicted. The data that we came across seems to propose that cartels have been using different types of narco-submarines concurrently; hence, they seem to be employing a mixed strategy.

This study is important and relevant to the present challenges faced by law enforcement authorities and militaries. This effort seeks to add value to the existing literature on the subject as it contains several essays which describe the complexity of the challenges that narco-submarines present. The document also provides the background and context behind the emergence of these vessels. Furthermore, the work illustrates the evolution of narco-submarine technology and the advances in their design, features, and technical capabilities.

Finally, it is important that we collectively consider the potential of these types of vessels to transport more than just narcotics: the movement of cash, weapons, violent extremists, or, at the darkest end of the spectrum, weapons of mass destruction.

While this is a volume that will be of general interest to anyone with an interest in global security, the intended readers are military, homeland security, and law enforcement personnel who wish to learn more about these vessels and their respective capabilities. Policymakers and analysts may also find the work useful for understanding the detection and interdiction challenges that these vessels generate. Increasing the area of knowledge about narco-submarines should enrich and deepen our understanding of the threat they pose to our domestic security, and indeed to the global commons.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

On one side, drug cartels attempt to optimize their operational efficiency while mitigating the risk of detection, seizure, and capture. On the other side, we have law enforcement and militaries’ efforts to improve their surveillance and detection capabilities. This race to out-flank and counteract one another has led to the development of narco-submarines.

On one side, drug cartels attempt to optimize their operational efficiency while mitigating the risk of detection, seizure, and capture. On the other side, we have law enforcement and militaries’ efforts to improve their surveillance and detection capabilities. This race to out-flank and counteract one another has led to the development of narco-submarines. This work is anticipated to appear in the Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) website as unclassified research conducted on defense and security issues that are understudied or under-considered. The work contains a preface written by Dr. James G. Stavridis, and a number of essays written by U.S. Navy Captain Mark F. Morris, Adam Elkus, Hannah Stone, Javier Guerrero Castro, and Byron Ramirez discussing and analyzing narco-submarines. The paper also comprises a comprehensive photo gallery, arranged in chronological order, which allows the reader to observe the evolution of narco-submarine technologies. It also contains a cost benefit analysis of using narco-submarines, as well as a map and a table that highlights where these distinct narco subs were interdicted. The data that we came across seems to propose that cartels have been using different types of narco-submarines concurrently; hence, they seem to be employing a mixed strategy.

This work is anticipated to appear in the Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) website as unclassified research conducted on defense and security issues that are understudied or under-considered. The work contains a preface written by Dr. James G. Stavridis, and a number of essays written by U.S. Navy Captain Mark F. Morris, Adam Elkus, Hannah Stone, Javier Guerrero Castro, and Byron Ramirez discussing and analyzing narco-submarines. The paper also comprises a comprehensive photo gallery, arranged in chronological order, which allows the reader to observe the evolution of narco-submarine technologies. It also contains a cost benefit analysis of using narco-submarines, as well as a map and a table that highlights where these distinct narco subs were interdicted. The data that we came across seems to propose that cartels have been using different types of narco-submarines concurrently; hence, they seem to be employing a mixed strategy.