By Matthew W. Gamble

Introduction

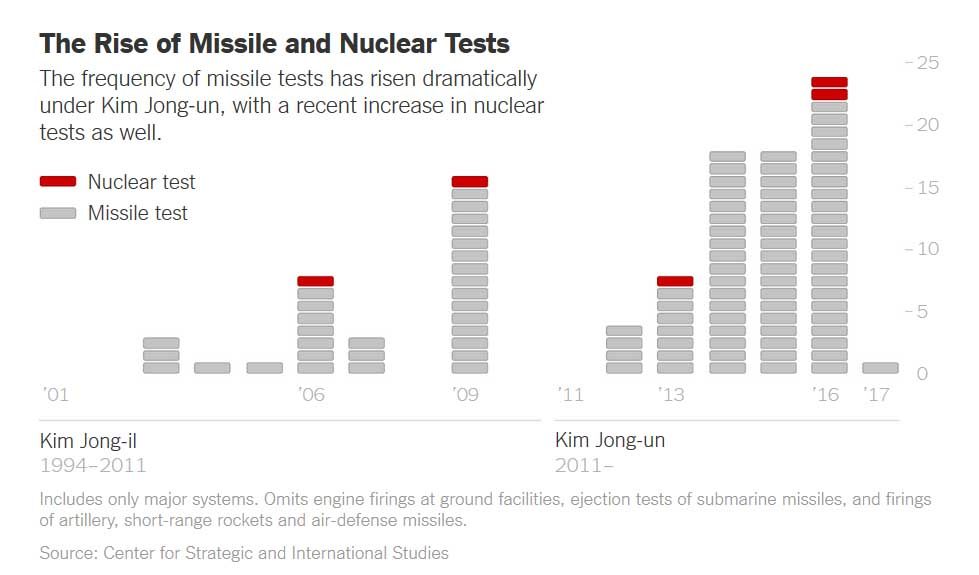

North Korea stunned the world by conducting its first nuclear test in 2006, a mere three years after its withdrawal from the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. Despite the small, one-kiloton yield of the device, the test nevertheless signified the rogue state’s entry into the nuclear arena and further complicated the already strategically challenging position on the Korean Peninsula. A recent report by the U.S.-Korea Institute at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies estimated that Pyongyang currently possesses a growing stockpile of between 10-16 nuclear weapons, though the exact number remains unknown. More alarming are the rapid advancements North Korea has recently made in developing nuclear weapon delivery systems, including the recent missile test-launch on May 14th showing considerable progress toward an intercontinental ballistic missile. Considerable resources have been devoted to this pursuit by the famine-stricken state, and investments are beginning to bear fruit. Despite its emphasis on land-based systems such as the new Hwasong-12, North Korea’s evolving sea-based nuclear delivery potential is beginning to pose a considerable threat, lending additional credibility to the Kim regime’s nuclear deterrent.

Nukes at Sea

Of particular concern, North Korea has been making progress toward attaining a nuclear triad by developing a submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) capable of delivering a nuclear warhead. After several failures, the DPRK successfully tested its first SLBM, known as the Pukkuksong-1/KN-11, in late August 2016. With a two-stage solid fuel propellant system, the KN-11 has an estimated range of almost 500 nautical miles, more than enough to threaten major population centers such as Seoul and Tokyo, or military installations like Kadena Airbase in Okinawa, with only limited travel of its launch platform outside of home waters. Notably, it seems the decision was made to opt for a more stable, solid fuel propellant at the expense of range after a series of liquid-fueled missile failures. Not only is a solid fuel propulsion system less volatile, but it enables the missile to be launched on short notice, as it does not require the lengthy and dangerous fueling process required before the launch of a liquid fueled ballistic missile. Currently, the operational status of the KN-11 is unclear, with estimates of service entry varying from late this year to 2020.

In addition to technical advances in SLBM technology, North Korea has made considerable progress in developing a new class of submarine for the Korean People’s Navy (KPN) capable of deploying these weapons. With the first vessel launched in the summer of 2014, the Sinpo-class represents Pyongyang’s first diesel-electric ballistic missile submarine. Similar in size and shape to older Yugoslavian designs like the Heroj-class, the Sinpo-class appears to have incorporated features derived from the Soviet Golf II-class ballistic missile submarine. Indeed, in 1993 North Korean technicians had the opportunity to examine a number of ex-Soviet Pacific Fleet Golf II-class boats before they were scrapped.

When looking at the Sinpo’s ballistic missile launch tubes, the influence of older Soviet designs becomes apparent. In a similar arrangement to the Golf II, a rectangular section of the conning tower houses what appear to be one or two ballistic missile launch tubes. Likewise, given its diesel-electric propulsion system, the Simpo-class shares the Golf-class’ range limitation, estimated to be around 1,500 nautical miles. When paired with the moderate range of the KN-11, the Sinpo-class would require fueling to achieve launch distance of the continental United States. Nevertheless, once made fully operational, these submarines could potentially threaten strategic targets throughout East Asia and could prove difficult to track and eliminate. Moreover, a ballistic missile submarine can launch its SLBMs from a variety of directions, complicating missile defense planning and increasing the vulnerability of potential targets.

Currently, only one Sinpo-class ballistic missile submarine appears to be active, but additional vessels will likely be completed in the near future. The submarine reportedly suffered damage to its conning tower on 28 November 2015, after a KN-11 failed to successfully eject from its launch tube during a test. Nevertheless, on 24 August 2016, a successful test was conducted where a KN-11 was launched from the vessel. Despite this success, the operational status of North Korea’s SLBM capability remains unclear. Ultimately, the Sinpo-class remains the largest submarine built for the KPN and will represent a significant enhancement of North Korea’s nuclear delivery capacity once perfected, though its small size, limited range, and rudimentary design are substantial shortcomings.

Complicating Deterrence

The addition of an SLBM, complemented by a workable launch platform, will greatly enhance the survivability of North Korea’s nuclear delivery capacity and improve the credibility of its nuclear deterrent. Currently, North Korea’s land-based nuclear delivery systems rely heavily on fixed infrastructure and operate in the open, which makes them particularly vulnerable to attack. As a result, if Washington were to lose ‘strategic patience’ with the DPRK, Pyongyang would likely see its land-based nuclear forces neutralized in a first strike. Ballistic missile submarines, on the other hand, are more survivable than fixed infrastructure because the vastness and depth of the oceans provide concealment within a wide operational area.

Though the anti-submarine warfare (ASW) capabilities of the combined U.S.-ROK forces are second to none, even a rudimentary submarine such as the Sinpo-class would be difficult to locate and destroy quickly. Consequently, it is plain to see how a ballistic missile submarine would enhance North Korea’s nuclear deterrent. If the DPRK were to ever lose its land-based nuclear delivery systems in a surprise attack, it would still have the ability to retaliate with an SLBM launch against South Korea or Japan. Politically, this would alter the cost-benefit analysis when weighing military action against Pyongyang. Once the nuclear armed Sinpo-class becomes fully operational, it will be even more difficult for the United States to guarantee the complete elimination of all North Korean nuclear delivery systems in a first strike. Under those circumstances, it seems unlikely that South Korea would agree to any preemptive military action against North Korea. Therefore, the scope of action that can realistically be taken against the rogue state is diminished, granting the Kim regime additional political leverage on the international stage. With this in mind, the significance of a fully operational nuclear armed North Korean ballistic missile submarine becomes abundantly clear.

The Range of DPRK Seaborne WMD Threats

Given the range limitations and reliability issues associated with North Korea’s current arsenal of ballistic missiles, the Kim regime may turn to unconventional methods to deliver nuclear weapons to targets well outside the range of its missiles. In the extreme, North Korea could smuggle a nuclear or radiological weapon in a shipping container aboard one of its numerous merchant vessels. A 2005 report by the Congressional Research Service titled, “Terrorist Nuclear Attacks on Seaports: Threat and Response,” highlighted the challenging nature of preventing such an attack. Certainly, North Korea has already demonstrated its willingness and ability to smuggle contraband aboard its merchant vessels undetected.

In 2013, a North Korean-flagged freighter, the Chong Chon Gang, traversed parts of the Pacific undetected after disabling its Automatic Identification System. Eventually, the freighter made it to the Panama Canal where its illicit cargo was discovered after being boarded by Panamanian port authorities. Fortunately, in this case its cargo merely consisted of surface-to-air missile components, disassembled MiG-21s, night-vision goggles, and ammunition. Yet, if the ship was transporting a nuclear or radiological device, the damage that could have been inflicted upon the Panama Canal would have been substantial.

For North Korea, smuggling a nuclear device on a freighter would be a high-risk high-reward strategy. A successful smuggling operation followed by a detonation in close proximity to the intended target could serve as the first strike in the opening of a larger war. On the other hand, if the nuclear cargo was intercepted en route to its destination, North Korea would lose the element of surprise and open itself to a retaliatory attack. Although it is unlikely that North Korea would opt to smuggle a nuclear weapon aboard one of its merchant vessels, the threat should not be discounted entirely.

Conclusion

Recent developments in the sea-based nuclear delivery capacity of the KPN have complicated the strategic situation on the Korean Peninsula even further. By diversifying the means by which it can deliver nuclear weapons, the Kim regime has strengthened the credibility of its nuclear deterrence, forcing the U.S. and its allies to think twice before considering military action. Although the North Korean military would eventually succumb to the overwhelming force of American-ROK full-spectrum dominance in a full-scale war, the possibility of nuclear strikes against South Korea and Japan would likely be considered an unacceptable risk by political leaders, thereby taking the option preemptive military action against North Korea off the table. Meanwhile, the threat of nuclear smuggling looms large, adding an additional layer of complexity to the North Korean nuclear problem.

As the DPRK continues to perfect its missile technology, we may one day see Pyongyang with the ability to deliver a nuclear weapon to the continental United States with an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). At this point, whether or not to pursue a strategy of forcible denuclearization is up for debate, but given this turn of events it seems the window of opportunity to do so is closing rapidly.

Matthew Gamble is based in New Brunswick, Canada. His research interests primarily focus on Eurasian geopolitics, capability analysis, and Canadian defence policy. Find him on twitter @Matth_Gamble.

Featured Image: North Korean underwater test-fire of submarine-based ballistic missile. (KCNA/via Reuters)