By Bill Shafley

A destroyer squadron (DESRON) staff’s employment as a Sea Combat Commander in the Composite Warfare Commander (CWC) construct is unnecessarily narrow and prevents a more lethal and agile strike group. Tomorrow’s fight requires multiple manned, trained, and certified command elements. These elements should be capable of maneuvering and employing combat power. This combat power is required to support area-denial operations, assure the defense of a high-value unit, or conduct domain-coordinated advance force operations to sanitize an operating area in advance of the main body. This ability to diffuse command and control, disperse combat power, and contribute to sea control operations is imperative to fully realize the Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) concept.

The Fight

The carrier battle groups (CVBGs) of the Cold War evolved into the carrier strike groups (CSG) of today. The components of the CWC organization did as well. The CWC organization evolved into managed defense of a high-value unit to preserve the capability of the carrier air wing (CVW). A destroyer squadron staff embarked on a Spruance-class destroyer managed multiple surface action groups (SAGs) and search and attack units (SAUs). They managed a kill chain designed to prevent submarines and surface ships equipped with anti-ship cruise missiles from ever entering their weapons release lines. As the anti-submarine warfare commander, they also managed the up-close defense of the carrier through assigning screening units and maneuvering the force as necessary to defend the ship and the air wing.

As the CVBG evolved into the CSG of today, the offensive and defensive missions were merged into one. The DESRON Staff was employed as the sea combat commander. The staff left the ships and embarked on the carrier. As maritime forces operated in support of land campaigns with precision fires far afield in mostly benign waters, defense of the CVN as a sortie generation machine became a primary mission. The carrier defense problem could be managed with one or two multi-mission cruisers or destroyers because the mission was generally limited to confined strait transits, managing a layered defense against fast attack craft, and establishing airspace control. The remainder of cruiser and destroyer offensive capability was chopped about between in-theater task force commanders to meet additional missions of interest, namely maritime interdiction and critical maritime infrastructure defense, and support to security cooperation plans. Near the conclusion of deployment, the strike group elements rejoined and went home together. This evolution has been fit for purpose over the last 25 years, but no longer.

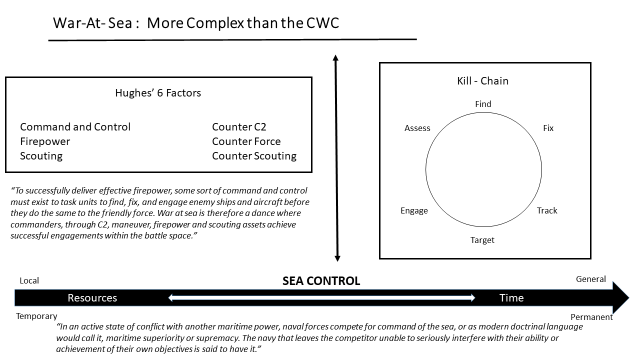

The fight of tomorrow looks more like the fight planned for during the Cold War, with one major difference. China’s blue water fleet is quickly becoming more capable than the Soviet fleet ever was. Consequently, the wartime employment of tomorrow’s CSG must focus more on offensive employment in sea control operations while also facing greater threats. These operations are uniquely maritime as they are focused on the destruction of an enemy fleet and its components that may impact the United States Navy’s ability to operate with superiority. Commanders in this environment manage scarce resources (see fig 1) to establish and maintain a kill chain while assuring adequate defense. A CSG must fight into an environment, survive, exploit sea control, and be prepared to move and establish it again; perhaps multiple times. Each CSG, with the CVN, its air wing, the fires resident in the VLS tubes of the DDGs, needs to be preserved as a fighting unit in order to generate the combat power necessary to achieve sea control while assuring its survivability through subsequent engagements.

The defense of the carrier must now be balanced with the work necessary to survive as a complete task-organized force. The greater the demand for sea control in time and space, and the greater the enemy force contesting sea control, the more offensive firepower will be required to neutralize the enemy and establish sea control. At the same time, this enemy force may also out-range many of the CSG’s weapons, might shoot first, and will shoot back. This threat environment increases the requirement for defensive firepower. This is a conundrum for the traditional approach. As the DMO concept suggests, disaggregation of the CSG is driven now by lethality and survivability.

As the above graphic notes, this tactical problem is far more complex than one of classic CVBG defense. Establishing sea control requires an optimized balance between offense and defense. This dilemma poses interesting questions. How much of the combat power of a CSG is left behind in defense? How much of it is committed to strike hard and win the war at sea? How is the offense commanded and controlled? Is there adequate command element (CE) depth to manage the CWC defense in one area and hunt/kill in another? What is the nature of the CE for these missions? Where should the CE be embarked for greatest effectiveness? How robust is it? What is the duration of the mission? The DMO concept requires command elements that, through the use of mission command can control all facets of sea control operations (to include logistics), in communications denied environments and at scale.

Today’s CSG commander lacks command and control options to address these questions. A differently manned, trained, and employed DESRON staff could provide this flexibility. This staff is at its core a command element. It could be ashore working for the numbered fleet commander as a combined task force (CTF) commander one week, embarked on a command platform the next week, and on the carrier the week after that. It might even be dispersed to all of those at once and with multiple units under tactical control (TACON). This flexibility gives higher echelon commanders multiple employment options as they consider how to delegate their command and control to meet mission needs. However, the DESRON of today is not manned, trained, or certified to be employed in this manner.

Manning Concept

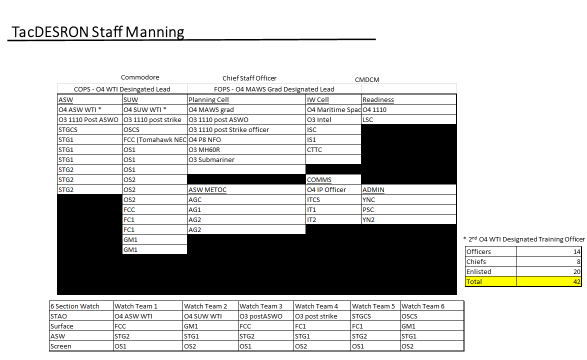

The proposed command element would require watch standers and planners, including enough subject matter experts to plug into multiple battle rhythm events. The command element would have cells for current operations (COPS), future operations and plans (FOPS), information warfare (IW), and readiness. It would be manned to provide a six-section watchbill, a distinct and separate planning team, an IW cell and readiness monitoring team that would coordinate with fleet logistics and maintenance support for assigned ships. The six-section watchbill requirement would afford the staff enough personnel to split and establish command and control in two different locations for missions as assigned. This staff size is roughly equivalent to current DESRON manpower levels (40-45 personnel). Its makeup in terms of subject matter expertise is more tailored to the Sea Control mission set.

This new DESRON staff would be manned as follows:

Training Concept

This command element should be educated and trained to apply joint warfighting functions with multi-domain maritime resources to establish, execute, and maintain a kill chain in an assigned geographic area. This is a robust capability that can be brought to bear in defense of high value units, in intelligence preparation of the battlefield, in surveillance and counter surveillance, or in direct action against enemy surface and subsurface units.

This organization is led by a major command selected captain (O6) surface warfare officer. This officer should have significant tactical experience in command as a commander (O5), have received a Warfare Tactics Instructor certification, and/or graduated from an advanced in-residence planner course (Maritime Advanced Warfighting School, School of Advanced Air and Space Studies, School of Advanced Warfighting, School of Advanced Military Studies). Experience on squadron, strike group, or fleet staffs would also be beneficial. The chief staff officer would be an O5, post-command officer of similar qualification. Service as the chief staff officer should be viewed as a career enhancing opportunity in the 5 years between O5 command and O6 major command. The leadership of this team would be rounded out by a billeted and selected command master chief.

Officers assigned to the staff should be proven shipboard operators in the all the major warfare areas. They should be qualified as ASW Evaluators and Shipboard Tactical Action Officers. Four post-department surface warfare officers would be assigned to the staff. They would serve as lead officers for current operation (COPs), future operations and plans (FOPs), training, and readiness, and serve staggered 24 month tours. Officers would follow an assignment track within these billets to afford experience in all four jobs, culminating as COPs or FOPs. These leaders should be post-department head officers eligible and competitive for command at sea.

There would be four post-division officer tour officers assigned to this staff structure. These would be qualified as surface warfare officers and served as an Anti-Submarine Warfare Officers/Evaluators, Tomahawk Engagement Control Officers, and/or hold Warfare Coordinator Qualification. These officers would be selected for department head and due course, that is, competitive for further advancement. All of these officers would attend the Staff Watch Officer, Joint Maritime Tactics Course, Maritime Staff Officer’s Course, and specialty schools as necessary. Officer who trained with foreign navies at their principal warfare officer courses and planning courses would also be sought after to bring Coalition Integration to bear.

There would be 3 senior chiefs and 8 chief petty officers permanently assigned to this staff. The senior chief petty officers (SCPOs) would be from the ratings of Sonar Technicians, Operations Specialists, and Information Systems Technicians each would have successfully completed shipboard leading chief petty officer (LCPO) tours. They should respectively hold advanced Navy Enlisted Classifications in the ASW field, achieved senior-level air controller qualifications, and hold Communication Watch Officer and associated computer network management credentials. Assigned LCPOs in rates depicted would provide technical and watchstanding expertise in their rate. All SCPO and CPOs would complete the STWO/JMTC course work and additional rate specific training. The remaining enlisted sailors would be first or second class petty officers (E6/E5), and trained as watchstanders to support the 6 section watchbill and planning cell.

This staff would include support from additional warfare communities. The IW cell would be comprised of a lieutenant commander (O4) maritime space officer and a lieutenant (O3) intelligence officer. The IW community would provide a lieutenant commander (O4) Information Professional officer to manage communications requirements for this rapidly-deployable team. The team would be rounded out with the addition of two aviators: an MH-60R pilot and a P-8A naval flight officer. Their experience would be crucial in planning and for watchstander assistance during training and operations.

Certification Process

The proposed DESRON staff would be assigned to the Carrier Strike Group commander for administrative purposes. The DESRON staff would follow the Carrier Strike Group’s optimized fleet response plan (OFRP) progression (i.e., maintenance phase, basic phase, advanced phase, integrated phase, deployment, and sustainment phase). The staff would be deployable from deployment through the end of sustainment phase, and its qualifications would lapse as the CSG entered the maintenance phase.

Over the course of the OFRP maintenance phase, the staff would go through a personnel turnover period, to include key leadership. The primary purpose of this phase would be to establish the staff’s training plan. The WTIs would tailor the staff training plan based upon lessons learned from previous employment and potential future assignments. This training plan would incorporate the latest in tactical developments and experimentation. Furthermore, participation in table top exercises, Naval Warfare Development Command wargames, and Fleet 360 programs would be included. This training plan would be approved by the Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center (SMWDC) and enacted by the appropriate tactical training group (Atlantic or Pacific), the Naval War College, and various warfare development commands.

The staff’s basic phase would mirror a ship’s in length and complexity by field. Staff WTIs, along with the appropriate tactical training group, would craft scenarios that build in complexity and the amount of integration with the individual cells. The staff would benefit from staff rides to all of the warfare development centers, and significant time at the tactical training group to learn cutting edge tactics, techniques, and procedures and capabilities and limitations. Through the use of live, virtual, and constructive training tools, the staff would train to the Plan, Brief, Execute, De-brief (PBED) standard in stand-alone work before gradually integrating the staff. The DESRON commander would focus on crafting intent, planning guidance, and risk assessment. The IW Cell would conduct Intelligence Preparation of the Operating Environment, the planners learn the effective use of base plans, branches, and sequels, and the watch standers would execute these in scenario work. The basic phase would culminate with the entire staff certifying over a week long exercise where the team operates in a higher headquarters battle-rhythm driven environment and is certified to a basic standard by Tactical Training Group Atlantic or Pacific (TTGL/P).

The advanced phase would begin with the DESRON staff executing Surface Warfare Advanced Tactics and Training (SWATT) at-sea with SMWDC mentors with live ships, submarines, and aircraft. This exercise mimics the training conducted during the basic phase. In this program, the staff embarks a platform and integrates with the assigned ships and operates at-sea introducing frictions not seen in the live, virtual, or constructive environment. Watch sections and planning teams would be assessed again in-situ and performance assessed to assure continued development. The SMWDC senior mentor would then recommend advanced certification to the certifying authority. If practical, the staff should embark aboard the CVN with the CSG for Group Sail (GRUSL) for additional training opportunity prior to the pre-deployment Composite Training Unit Exercise (COMPTUEX, or C2X).

The COMPTUEX would remain the final hurdle in integrated training leading to deployment certification. Over the course of the 6 weeks at-sea, the staff would have to demonstrate its capability in integrating into the CSG battle rhythm and demonstrate watch stander acumen in increasingly complex live exercise (LIVEX) evolutions.

During the COMPTUEX, the DESRON Staff would have to demonstrate its capability to act as a CTF commander afloat, both on the CVN and embarked in a smaller unit with assigned units. It must demonstrate the capability to conduct “split-staff” operations at a remote site ashore. In each of these instances, the staff must demonstrate its capability to establish C2 of assigned units for mission effect, control operations effectively, and integrate into a higher headquarters battle-rhythm.

Satisfactorily assessed in these areas, the staff would be certified to deploy. During deployment, it would be employed flexibly and with optionality based upon the tactical situation and the desired effects from commanders at-echelon. As the CSG heads over the horizon, the DESRON staff could participate in fleet battle problems (FBP) and coalition-led exercises to test and validate a whole range of new tactics, techniques, procedures, doctrine, and interoperability. As FBPs continue to develop and live, virtual and constructive training tools come on line, the chance to “fail fast” in this space only increases.

Employment Concept

The proposed tactical DESRON could be employed across a wide range of operations supporting Carrier Strike Groups, Amphibious Ready Groups, and fleet commanders. Mission and associated tasks drive span of control in terms of assigned ships, aircraft, and additional resources. As a task organized, employed, and expeditionary staff, its main value prospect would be its flexibility.

Manned, trained, and certified during the intermediate and advance training phases, the command element’s normal mode of operation would be embarked aboard a command ship. Employed to protect a command ship, it would be capable of exercising warfare commander duties in a strike group/CWC environment with up to five assigned ships. While its primary missions would remain anti-surface and anti-submarine warfare, it could augment or establish additional warfare area support (Integrated Air and Missile Defense or Information Warfare) in any surface combatant. Employed as a scouting force further afield in the assigned operating areas, a portion of the staff may embark detached assets to afford command control and transition scouting missions into local maritime superiority missions. Employed as a task force commander, it may disperse further and move ashore with a local fleet commander to oversee operations over a broader area. Though this employment method would be more taxing on the staff, it might be required for short durations of high operational tempo. With basic manning and training levels achieved, the command element could be employed to C2 joint exercises or lead TSC missions ashore with partner nations as part of its further development.

The sustainment phase would be the most important of all for this staff because it would be key to force-wide improvement. Over the course of a deployment, the DESRON staff would have participated in various operations and exercises. Based on these experiences, the staff training officer would lead a robust program of lessons learned. The assigned WTIs would also compile and prepare various tactical notes and after action reports to share amongst other DESRON staffs and units alike. As the staff transitioned into its maintenance phase, it would go “on the road” to debrief its lessons learned, new tactical and doctrinal proposals with the goal of driving organizational learning for future operations. The habitual relationships with War College and its various research groups, the warfare development commands, and SMWDC WTI community makes for an amazing opportunity to share experiences, connect subject matter experts and further development efforts across the fleet.

Conclusion

This concept is aspirational and developed without respect to resources. There are numerous additional details necessary to bring a capability like this to fruition, but none of these details require new thinking to manage. Commitment, purposeful planning, and some smart staff work would be adequate to address each on in turn. A capability like this could be developed within the 5-year Future Year Defense Program/Program Objective Memorandum cycle. The staff’s full capability will be realized over time as new business rules for assignment are enacted. The certification criteria would be amended and in some cases completely developed. But much of this infrastructure, the school houses, the courseware, and training systems already exists.

This model makes no mention of permanently assigned surface ships to the DESRON. This work presupposes that ships assigned to the squadron arrive manned, trained, equipped and certified at the basic level. Ships change operational control to the DESRON for employment via formal tasking order. Readiness oversight functions of this staff are limited across the board. This staff retains a strong working relationship with the various type commands and local maintenance centers to assure in-situ readiness issues can be resolved.

The deployment and sustainment phases of the OFRP are vital to successful maintenance and basic phases for the next set of employment. The DESRON staff responsibility in this work is to assure that the events prescribed by the Surface Force Readiness Manual are scheduled, are thoroughly completed by assigned units, and that long-term readiness risks are endorsed. Once sustainment phase is complete, the assigned ships are returned via “chop” in the same official manner. Readiness oversight success in this environment means that ships have true and complete self-assessments with ample transparency of emergent and voyage work necessary to maintain assigned readiness conditions.

The proposal for a tactical DESRON represents an opportunity to leap ahead of the competition and bring the elements of speed, synchronization, and surprise to the employment of naval forces. The CSG and ARG as units of employment have been disaggregated for most of the last 20 years in an effort to get the most out of assigned theater maritime resources. Forces have been chopped up and moved about amongst standing fleet task forces, leaving the strike group staff in most instances over-billeted in terms of staff capability. This has left DESRON staffs as the under-employed adjuncts of CSG staffs and merely augmenting the battle-rhythm. This proposal to invest in the DESRON staff and reorient it towards looming challenges would correct these trends and yield a more lethal force for employment within the Distributed Maritime Operations concept.

Captain Bill Shafley is a career Surface Warfare Officer who has written extensively on strike group operations, mission command, and sea control in this forum and others. He has served on both coasts and overseas in Asia and Europe. He is a graduate of the Naval War College’s Advanced Strategy Program and a designated Naval Strategist. These views are presented in a personal capacity.

Featured Image: PHILIPPINE SEA (June 18, 2022) Sailors aboard Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Spruance (DDG 111) handle lines during a replenishment-at-sea with Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72). Abraham Lincoln Strike Group is on a scheduled deployment in U.S. 7th Fleet to enhance interoperability through alliances and partnerships while serving as a ready-response force in support of a free and open Indo-Pacific region. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Taylor Crenshaw)