This article is part of CIMSEC’s “Forgotten Naval Strategists Week.”

The fleet reflected the empire it served. The centuries-old dynasty that expanded its rule with an iron fist continually fell back on its own hubris, believing its decisions like a cloak of Catholic papal infallibility and that its enemies were incapable of mounting any serious challenge. The Romanov dynasty, and its courtiers, ignored the factors that enabled their primacy, unable to foresee their own demise within a decade; and it was with this aura of invincibility that the Baltic Fleet was ordered on its months-long journey to the Far East. But that aura wore off quickly and gave way to the relentless cold, penetrating rain as the fleet got underway, foreshadowing the hail of Japanese shells that would ultimately devastate them. As one Russian officer wrote a year later, “surely this was no day to inspire hope in the hopeless…and a hopeless band it was.” (White, p. 597) The eventual battle in the straits of Tsushima, as with earlier engagements between the two powers during the Russo-Japanese War, reflected the works of Admiral Stepan Makarov. Japanese adoption of his concepts led to its victory; Russian rejection led to its defeat.

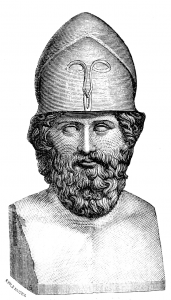

Russia failed to prepare for war. It neglected to provide appropriate maintenance of its fleet, provision its ships, or appropriately train and educate its personnel. Russia had the opportunity to comply with their top theorist but failed to do so. Admiral Stepan O. Makarov (or Makaroff prior to 1918), was widely published on naval theories as well as a practitioner. Makarov, who had graduated first in his military class, published his first article at the age of 19 in Morskoy Sbornick, the Russian version of Naval Institute’s Proceedings. He eventually published over fifty books, articles and major papers. He was an early proponent of wireless communication between ships – which was later used by the Japanese instead of the Russian Navy. With the advent of torpedoes, he designed torpedo boats as well as torpedo boat tactics for the Russo-Turkish War.

Russia failed to prepare for war. It neglected to provide appropriate maintenance of its fleet, provision its ships, or appropriately train and educate its personnel. Russia had the opportunity to comply with their top theorist but failed to do so. Admiral Stepan O. Makarov (or Makaroff prior to 1918), was widely published on naval theories as well as a practitioner. Makarov, who had graduated first in his military class, published his first article at the age of 19 in Morskoy Sbornick, the Russian version of Naval Institute’s Proceedings. He eventually published over fifty books, articles and major papers. He was an early proponent of wireless communication between ships – which was later used by the Japanese instead of the Russian Navy. With the advent of torpedoes, he designed torpedo boats as well as torpedo boat tactics for the Russo-Turkish War.

Makarov studied foreign wars. Writing following the Spanish-American War, he suggested the lessons showed that: navies must rely on its guns; they must never sacrifice artillery to armor; more artillery and torpedoes are necessary; armor doesn’t assure victory, it only retards the defeat; and a victory exacts the same conditions on land and sea. (Makaroff, “Views of the Lessons of Santiago”) One author evaluating Makarov in a 1965 Proceedings article noted had he “been born in other times and circumstances, he might well have been one of the world’s universal geniuses.”

Makarov’s seminal work proved as diverse in its theoretical, operational, and tactical considerations as other strategists. The first tenet, like that of Sun Tzu, was the influence of morale upon success in battle. To prove this historically, Makarov focused largely on Admiral Horatio Nelson. So close was he to Nelson’s order before Trafalgar, (“No captain can do very wrong if he places his ship alongside that of the enemy”) that he developed his own corollary, “only he who does nothing never errs.” In his detailed study of Trafalgar, he notes that Villeneuve “displayed a dejected frame of mind.” (Makarov, Tactics, p. 78) He quotes Napoleon that “you must tell cowards that they are brave men if you wish them to be so.” (Makarov, Tactics, p. 81)

In studying the Battle of Santiago, Makarov again noted the importance of morale since the Americans were confident in artillery and sought combat; the Spanish, by contrast, “came out of Santiago with the absolute certainty of meeting the disaster that awaited them.” While in Port Arthur under attack, Makarov personally took command of the Novik and left the safety of the harbor to render assistance to another ship, displaying the boldness that resulted in Nelsonian loyalty throughout the Russian fleet.

He wrote that “the maintenance of proper spirit on shipboard is a matter of the highest importance.” (Makarov, Tactics, p. 45) Such was clearly not the case when the Baltic Fleet got underway there “nothing but toil discomfort, anxiety” (White, p. 597) and later learned of the Asian Fleet’s fate, having weeks more to contemplate what awaited them.

The second tent was training and education. “Officers and men must be trained so as to fit them for war,” he wrote. Lieutenant R.D. White writing in Proceedings about Tsushima suggested that one of the flaws of the Russian fleet was that the Baltic Fleet’s Admiral Rodjestvesnski held his “first practice maneuvers with his whole squadron the day before the battle.” Another officer blamed the Minister of Marine who allegedly suppressed the Grand Naval Maneuvers, condemning the squadrons “to an enforced idleness.” Furthermore, “only one staff officer had received a military education.” The Russian officer related that “every Russian will answer, ‘Ah, if Makaroff had been there.’”

The third tenet was the use of ordnance. His statement that “firing without aiming is the best way to lose” was simplistic, but given the Baltic Fleet’s experience at Dogger Bank and Tsushima, the Russians would have been better served by targeting and improving their hit ratios. In Proceedings, Bradley A. Fiske assessed as a Commander and Inspector of Ordnance that the Japanese fleet’s handling was better; Japanese gunnery was better, and they were better prepared in war.” The Russians, due largely to nervousness and inexperience, were opening fire at 10,000 yards or more, which was too far to be effective, and many shells were simply defective. The Japanese, by contrast, reserved fire until they were within 6,000 yards until they closed to 3,000 yards. One Russian executive officer who survived the battle noted that the “principal cause of our defeat was our technical proficiency”.

The fourth tenet was the use of torpedoes, on which Makarov was one of the experts among all nations. From the advent of torpedoes as a new technology, to the design of torpedo boats, to the development of tactics, to the introduction of an entirely new type of warfare, Makarov was arguably without peer. In this, the Japanese were superior to the Russians during the conflict, inflicting heavy damage or deterring ships as a result.

The fifth tenet was “preparation for war.” His motto was “Remember War” – as if war were always imminent. Makarov arrived in Port Arthur in early March 1904. According to one of his officers, the “efficiency of the fleet was improved and [his] personality and drive inspired everyone under his command.” The Russian directive for Makarov’s forces at Port Arthur was simple: “Hold until reinforced.” The expectation was that the Far East Fleet should remain at anchor in the protection of the harbor. Makarov disagreed and ordered his ships to get underway as often as possible, often engaging Japanese forces. Had Russia adopted this tenet, the Baltic Fleet might have fared better at Tsushima. Makarov wrote that “Nelson understood how to maintain the health of his crew during long sea cruises,” a factor ignored by the Russian admiralty. Another issue was that the Baltic Fleet took mostly coal for its long voyage and not enough ammunition.

Finally, he supported the concept of the fleet working with ground forces to achieve victory (Makarov, Tactics, p. xxvi). The Russian land and naval forces had little coordination, with the exception of the one month Makarov was in Port Arthur. More adept at this type of joint operation was the Japanese Navy, Makarov’s influence and effectiveness were, however, mitigated by political and personal realities. First, some of his work wasn’t entirely original. In his Discussion of Questions in Naval Tactics, Makarov’s delves deep into Clausewitz, Jomini, Nelson, Napoleon and Russia’s own Geenral Dragomirow.

With regard to his own theories, some turned out to be outdated within years of his death. In his major work, for example, he devoted an entire chapter on the design and tactical use of ram ships, which some might suggest outlived their use with the Battle of Actium. But the 19th century was no stranger to ram ships. In 1835, Captain James Barron designed a tri-hulled, steam-driven paddle-wheel ram ship. Charles Ellet, Jr.’s ram ships found moderate success during the U.S. Civil War. Ramming was employed at the Battle of Lissa during the Austro-Italian War. Prow-configured capital ships for potential ramming continued to be incorporated into U.S. designs, such as with the USS Olympia.

Makarov also failed to successfully employ some of his own maxims. One was that one must risk to win battles. Another, as previously noted, was to illuminate harbors and employ reconnaissance boats. Ironically, a month after taking command at Port Arthur, he was advised that something was seen in searchlights outside the harbor. Believing it to be one of his own boats, he went to sleep. The following morning he risked all by getting underway; his ship soon hit a mine and Makarov was killed.

Makarov failed to gain sufficient support from his own government or fellow senior officers. Makarov was also at odds with the local Viceroy, Admiral Yevgeny Alexeiev, because he believed “politics and military matters did not mix,” a fatal flaw in someone who hoped his concepts would be implemented doctrinally. Tsar Nicholas II did not consider the Navy a priority, given Russia’s land-mass and need for a large standing army, until the waning months of the war.

Imperial Russia’s dependence on its land forces to protect its western borders and achieve its objectives in the east came at the risk of a marginal navy, ill-prepared for war, and failing to subscribe to the naval principles of one of its own admirals. That deficiency was exploited by the Japanese who not only studied Makarov’s principles but employed them at Port Arthur and Tsushima. This should not be surprising given that Fleet Admiral Heihachiro Togo “in all his travels kept Makarov’s book on naval tactics beside his bunk, until he almost knew it by heart.” (Warner, p. 238)

Works Consulted and Cited

BOOKS

- Makarov, Stepan O., Discussion of Questions in Naval Tactics.

- Podsoblyaev, Evgenii F. (translated by King, Francis and Biggart, John), The Russian Naval General Staff and the Evolution of Naval Policy, 1905-1914. The Journal of Military History 66 (January 2002): 37-70.

- Warner, Denis and Warner, Peggy, The Tide at Sunrise: A History of the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-05; Frank Cass, London 1974

ARTICLES from: United States Naval Institute Proceedings.

- Fiske, CDR Bradley A., “Why Togo Won”

- Japanese General Staff (Official Version), “Battle of the Sea of Japan”

- Lockroy, M., “The Lessons of Tsushima”

- Mahan, CAPT A.T., “Reflections, Historic and Other, Suggested by the Battle of the Japan Sea”

- Makaroff, S.O., “Views of the Lessons of Santiago”

- Makaroff, S.O., “Device for Minimizing the Effects of Collision at Sea”

- Mitchell, Dr. Donald W., “Admiral Makarov: Attack! Attack! Attack!” July 1965

- Posokhow, Admiral S., “Recollections of the Battle of Tsushima” aboard cruiser Oleg,

- Schroeder, CAPT Seaton, “Battle of the Sea of Japan”

- Sims, LCDR William S., “The Inherent Tactical Qualities of All Big-Gun, One-Caliber Battleships of High Speed, Large Displacement and Gunpower”

- White, LT R.D., “With the Baltic Fleet at Tsushima”

Claude Berube teaches at the U.S. Naval Academy. He is the immediate past chair of the Editorial Board of Naval Institute Proceedings. He is the co-author of three non-fiction books and the author of his debut novel, “The Aden Effect.”