This article by Lloyd Freeman is in response to our call for articles on Amphibious Warfare. Also, an editor’s reminder, we DO accept response articles at nextwar(at)cimsec.org.

The Marines are no longer America’s 911 force…and it gets worse: If the Marine Corps continues on its current trajectory of developing unrealistic operational concepts and platforms, it risks becoming irrelevant in light of much more capable U.S. warfighting organizations and platforms. The Marine Corps’ decision to go “all in” on the F-35B Joint Strike Fighter and its corresponding failure to embrace new, game-changing technologies and corresponding doctrine and tactics will result in a force that is ill-suited for next-generation warfare and will ultimately become subservient to other, much more capable U.S. military fighting forces.

The Marine Corps Goes It Alone

Over the past few years, the Marine Corps has started down a dangerous path of developing tactically and operationally unsound vision statements that are designed to protect their outlandish and expensive platforms. The Marine Corps recently rolled out their Expeditionary Force 21 (EF21) “vision,” which states that Marines will need to be able to conduct ship-to-shore operations from 65 nautical miles away—an incredible distance for any kind of surface assault. The analysis (or lack thereof….EF21 was developed independent of the U.S. Navy) behind EF21 is the belief that amphibious ships will be susceptible to coastal-defense cruise missiles (CDCMs). Rather than adhere to joint doctrine, for some inexplicable reason the Marine Corps has decided the way around enemy capability is not to neutralize but rather to swim right through it with future high-speed amphibious combat vehicles (ACVs). In light of U.S. technological dominance, this is puzzling. China has dug thousands of miles of tunnels and has constructed massive fuel-storage depots deep underground for a very obvious reason. Our potential adversaries know that if the U.S. military can see it, it can and will kill it. The Marine Corps refuses to accept that the U.S. Navy and the joint force will first set conditions for any possible future amphibious assault in accordance with Joint and Naval Doctrine, which currently allows for the first amphibious assault wave to be launched within 12 nautical miles (or closer)—not 65 nautical miles. Moreover, the Marine Corps does not consider the possible contributions of unmanned systems to future amphibious assaults. There is no need to place a single Marine into harm’s way if an autonomous system can swim onto or fly over the beach and provide the confirmation and subsequent destruction of enemy forces.

A thorough mechanical sweep of objective areas can be conducted with autonomous systems today in preparation for follow-on forces. It’s even possible that follow-on forces may not even be needed in an age of autonomous and unmanned systems. With such technological dominance at our finger tips, why is the Marine Corps still planning for a “Normandy”-type amphibious landing and creating concepts like EF21 that do not adhere to current doctrine and worse, do not attempt to maximize U.S. technological military dominance? The Marine Corps remains fixated on World War II tactics. This drives the procurement of outlandish and expensive platforms such as the Amphibious Combat Vehicle (ACV), or worse: platforms that are not even designed to support your operations and/or tactics….and herein lies the problem.

A 5th-Generation Fighter Mistake

Developing suspect doctrine is bad enough, but the Marine Corps’ procurement of platforms that are not designed to support its service-unique tactics and operating procedures only compounds the challenges it faces today. Although the short, take-off, and landing version of the F-35B Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) is possibly the best fighter jet ever built, it is not a close-air support platform and was never intended to be. The F-35 is designed for high-end, air supremacy operations during the setting of battlefield conditions that occur long before landing forces ever arrive in theater. Rather than pursuing aviation platforms ideally suited for close-air support, the Marine Corps aviation community hitched its wagon to the JSF program and now stands to join the elite-strike aviation community. However, in the joint arena, it is the job of the Air Force and Naval Aviation to conduct air supremacy operations. Marine Corps Aviation should be focused on supporting ground troops; close-air support has always been the ‘bread and butter’ of Marine Aviation….until now. The JSF 5th generation fighter is designed to penetrate enemy air defenses rather than loiter over a battlefield in support of ground troops. It truly is a difficult to understand how the Joint Staff and Congress approved such an expensive platform for procurement by the Marine Corps.

As a result of procuring a 5th-generation strike fighter, Marine Corps aviation has logically pursued employment options that actually match this new aircraft’s impressive capabilities. Marine aviation is currently focusing on turning the general-purpose amphibious assault ship (LHA) and the Wasp-class multiple-purpose amphibious assault ship (LHD)LHA/LHD amphibious ships into JSF platforms—essentially “light” carriers—which would deploy with up to 16 JSF platforms at the expense of rotary wing and embarked ground forces. Such an employment concept would provide true “bang for the buck” compared to the expensive deployment of the JSFs from the nuclear carrier fleet. However, for the Marine Corps, there is great danger in this path.

The Joint Staff and the Office of Secretary of Defense (OSD) are continuously challenged with the problems of sustaining and maintaining the current nuclear carrier fleet. The Marine Corps concept of using LHA and LHDs as light carriers would be a very attractive capability for policymakers, essentially creating a new, national strategic strike asset in support of national tasking vice support to Navy and Marine Corps amphibious ready group deployments. The Marine Corps aviation community has led the Marine Corps down a path of short-term gain with probably lethal long-term effects for traditional Navy/Marine Corps expeditionary missions. These are exciting times for Marine Corps aviation—right up to the point where the OSD and the Joint Staff determine that the LHA and LHD fleet would be better utilized deploying with a squadron of F-35B aircraft in support of national tasking vice serving as the central asset of the Marine Expeditionary Units. Marine pilots will love their new relevance as LHDs/LHAs and F-35Bs become national, strategic assets at the expense of the lost relevance of the Marine Corps as an expeditionary service. The Marine Corps infantry community is aware of the danger of the F-35B and winces at how much Marine capital has been consumed over a fighter platform that will probably rarely ever support Marine ground forces; but they have been disunited and fragmented in their opposition to the now powerful, Marine Corps Aviation community.

A Force Out of Touch

Very soon, the only relevant capability in the Marine Corps could be the JSF while the rest of the force is relegated to conducting low-end humanitarian-assistance and disaster-relief missions. In fact, if you look closely at the most recent Marine Corps commercials on TV that is exactly how the Marine Corps is depicted, a force providing disaster relief and humanitarian assistance, not an elite force closing with the enemy. Instead, the Special Operations Command (SOCOM) has taken on the higher-end, “911” mission sets that require capable, highly trained warriors and it has been extremely successful. SOCOM’s emergence as the new 911 force has been dramatic. It has led the way in leveraging technology with game-changing tactics to maximize technological dominance while employing a very small footprint. While the venerable USMC drill instructor is yelling at his candidates, the Navy SEAL instructor is quietly instructing his candidates how to put two rounds into the center of a target over and over again with devastating consistency. While young Marine lieutenants are learning how to operate and be comfortable in the fog of war, SOCOM operators have figured out how to lift it by using intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) “orbits” from drones and other platforms to provide clear, battlefield situational awareness through all phases of an operation. While the Marine Corps maintains a training curriculum that lauds the automatic response to orders, SOCOM seeks that rare breed of individual who is smart, in superior condition, and can think his way out of any problem or challenge. In other words, SOCOM wants the guys who don’t need orders.

In a world of game-changing technology, the Marine Corps has decided to keep playing the old, one-dimensional war game of running straight at your enemy yelling and hollering. Conversely, SOCOM has perfected the tactical art of surprise-utilizing stealth where the enemy never hears a sound or sees what hit him. SOCOM’s record, which includes killing the captors of Captain Richard Phillips as well as Osama Bin Laden, is already legendary. It has truly established itself as America’s new 911 force while the United States Marine Corps has been relegated to an outdated force.

The Need for New Doctrine

To be relevant today, the Marine Corps must revise its doctrine. It must outline how it plans to reestablish itself as a tier-one warfighting capability in a new operating environment in which amphibious operations will probably not require Marines to hit the beach in the same way they did over 60 years ago. As discussed earlier, Marine Corps doctrine is noticeably behind the times in leveraging unmanned systems and examining how this game-changing capability can and will be used in any future military campaign. Amphibious and Joint forcible entry doctrine will still be required. However, how we will do amphibious operations in the future probably differs dramatically from how the Marine Corps envisions it in EF-21.

While the Marine Corps continues to pursue costly, high-speed systems (such as JSF and high speed landing craft), it has yet to outline how an amphibious operation could be conducted with unmanned systems. The use of unmanned surface and aerial systems during the first waves of an amphibious assault would most likely dramatically change unit organization and tactics—and save lives. Furthermore, whether Marines want it or not, policymakers and the Joint Staff will probably force unmanned systems into the equation to reduce operational risk. Marines do not need to “hit the beach.” By letting drones conduct the first waves, follow-on Marines can then occupy ‘cleared’ ground and plan for follow-on missions. However, to make such an argument would call into question the wisdom and relevance of current Marine Corps programs such as JSF, which probably explains the silence among Marine Corps leaders when it comes to fostering real change.

Most Marine leaders would acknowledge that we will not fight a future war the same way we fought during World War II or the Korean War, yet they never seem to propose serious efforts to review current doctrine, organization, and what might be needed in light of emerging technologies and capabilities. Publications like EF-21 do not offer new doctrine but instead are repackaging of old strategies that propose the same old requirement for robust platforms that can bring Marines ashore from great distances offshore. Behind the glossy cover page is the same old World War II doctrine of “hitting the beach.”

Start Thinking Joint

The Marine Corps is notorious for ignoring the tremendous assets that are available in the Joint community. Hampering possible change is the Marine Corps’ fixation on the Marine-Air Ground Task Force (MAGTF), a holistic concept that aims to ensure it has an independent ability to logistically sustain a robust ground force with a capable aviation component in an expeditionary environment. The Marine Corps takes great pride in its ability to maintain this organic capability, but this has resulted in a reluctance to think outside Marine-Corps circles. Conversely, SOCOM is probably the most joint organization in the Department of Defense today and their results speak for themselves. SOCOM’s impressive performance reflects the very best capability of joint platforms that comprise its operating forces. Unfortunately, the Marine Corps continues to attempt “going it alone,” which is unfortunate: There are incredible intelligence/surveillance and support platforms that could enable the Marine Corps to conduct higher-end missions along the lines of SOCOM. Joint platforms such as predator drones, the P-3/P-8 Advanced Airborne Sensor, AC-130, or many of the other joint platforms would be much more conducive to supporting Marines on the ground. However, instead of investing in practical platforms ideally suited to supporting ground troops, the Marine Corps inexplicably decided to buy the multi-billion dollar JSF, a platform ill-suited to supporting ground troops.

The Marine Corps probably cannot reverse its commitment to the JSF. However, it can stop constraining itself to its own organic assets and reach out to the joint community to enhance its ground combat capability. The Marine Corps must also begin focusing resources on future platforms that can better support lethal, highly mobile ground forces that can leverage data-centric support platforms—or better yet, start pushing itself to begin operating more jointly during training and deployments as SOCOM presently does. However, to gain access and allocation of high-demand, joint assets, the Joint Staff and senior policymakers will probably want to know how the Marine Corps can contribute in today’s security environment. Focusing on lower-end security missions such as non-combatant evacuation operations and humanitarian assistance are not going to get anyone’s attention.

Change or Become Irrelevant

SOCOM is increasingly creeping into the missions that have historically been the bread and butter of the Marine Corps during peacetime operations. The Marine Corps must assess and revise its current organization from a top-heavy, rigid command structure designed to fight large land campaigns toward a smaller, better trained, highly skilled organization designed to conduct surgical strikes organized around robust ISR and advanced aerial strike assets if it hopes to get in on some of SOCOM’s action. Small high intensity missions will most likely dominate the security environment for decades to come. The Marine Corps could complement the capability of SOCOM by providing a more robust, combat-oriented version of SOCOM. This would of course require much greater cooperation with SOCOM and could affect Marine Corps manpower and training if SOCOM standards are to be met partially or in full. The Marine Corps needs to swallow the bitter pill and recognize that its current World War II organizational structure is outdated, impractical, and increasingly irrelevant on today’s battlefield.

The day of reckoning will come. Eventually, someone will again ask what makes the Marine Corps unique, and the F-35B JSF better not be the answer. The Air Force and Navy will have many more JSF platforms deployable from many more locations. By also failing to adapt ground forces to new tactics and doctrine and by failing to utilize new platforms that can virtually lift the “fog of war,” the Marine Corps is stuck in a time warp. New aspirational concepts such as EF21 that are not grounded in sound analysis and run counter to doctrine make the Marine Corps look even more disconnected and out of touch with modern tactics and technological capabilities. If the Marine Corps does not change and adapt to new technologies and tactics and focus on a clear vision of how it is to operate in the rapidly changing security environment, the future will consist of simply looking good in uniform.

Lloyd Freeman is a retired Marine infantry officer.

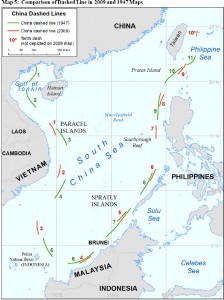

On December 5th, the U.S. State Department released its analysis of the compatibility of China’s nine-dashed line with international law. The report attempted to set aside the issue of sovereignty and explore “several possible interpretations of the dashed-line claim and the extent to which those interpretations are consistent with the international law of the sea.” The analysis found that as a demarcation of claims to land features within the line and their conferred maritime territory, the least expansive interpretation, the claim is consistent with international law but reiterated that ultimate sovereignty is subject to resolution with the other claimants.

On December 5th, the U.S. State Department released its analysis of the compatibility of China’s nine-dashed line with international law. The report attempted to set aside the issue of sovereignty and explore “several possible interpretations of the dashed-line claim and the extent to which those interpretations are consistent with the international law of the sea.” The analysis found that as a demarcation of claims to land features within the line and their conferred maritime territory, the least expansive interpretation, the claim is consistent with international law but reiterated that ultimate sovereignty is subject to resolution with the other claimants. If the actions taken by the United States, Indonesia, and Vietnam were surprising, China’s reactions were not. On December 7th, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs released a white paper of its own on the Philippines’ arbitration case. The document states that China’s policy, as established in its 2006 statement on UNCLOS ratification, is to exclude maritime delimitation from compulsory arbitration. Additionally, the paper says that while the current arbitration is ostensibly about the compatibility of China’s nine-dashed line with international law, “the essence of the subject-matter” deals with a mater of maritime delimitation and territorial sovereignty. The paper goes on to say that until the matter of sovereignty of the land features in the South China Sea is conclusively settled it is impossible to determine the extent to which China’s claims exceed international law.

If the actions taken by the United States, Indonesia, and Vietnam were surprising, China’s reactions were not. On December 7th, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs released a white paper of its own on the Philippines’ arbitration case. The document states that China’s policy, as established in its 2006 statement on UNCLOS ratification, is to exclude maritime delimitation from compulsory arbitration. Additionally, the paper says that while the current arbitration is ostensibly about the compatibility of China’s nine-dashed line with international law, “the essence of the subject-matter” deals with a mater of maritime delimitation and territorial sovereignty. The paper goes on to say that until the matter of sovereignty of the land features in the South China Sea is conclusively settled it is impossible to determine the extent to which China’s claims exceed international law.