Welcome back to another edition of the Members’ Roundup. There is an array of contributors featured in this week’s post. Topics range from exoskeletons in the Navy to assessing China’s nuclear arsenal. To kick off proceedings Natalie Sambhi, an analyst for the Australian Strategic Policy Insitute, has her own roundup of sorts called ‘ASPI suggests’ and provides a quick review of recent foreign policy and military developments.

With 2015 just beginning it is prudent that plans set in motion several years prior are reviewed and readjusted. The Center for Strategic & International Studies recently published a report on how the Administration and Congress can work together to sustain engagement with Asia. CIMSECian, Mira Rapp-Hooper, co-authors a chapter explaining how to adequately resource the Defense aspect the ‘pivot’.

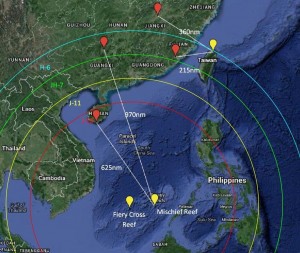

Of concern is the People’s Republic of China’s growing military power, of which its nuclear arsenal is becoming increasingly sophisticated. Kyle Mizokami writes whilst the nuclear force is modernising it is still relatively modest compared to other nuclear powerhouses, such as Russia and the United States. Kyle explores the history of Chinese nuclear pursuits and analyses some of the weapons in the nuclear arsenal in a post for The National Interest.

Over at Offiziere Canada-based CIMSECian, Paul Pryce, analyses recent developments of the Brazilian Navy. He argues that the label of a ‘green water’ navy was accurate in decades past but modernisation plans, however, suggest that it is well on its way to earning the ‘blue water’ title. You can access his article here.

Manpower issues will continue to be of concern for all military planners and leadership at all levels remains important during times of transition. Over at War on the rocks, Jimmy Drennan provides some thoughts on how to best provide leadership for personnel during ‘super deployments’ – deployments that are 9 months or longer.

Bringing the focus back to our Coast Guard colleagues, Chuck Hill continues to inform us of developments within the constabulary side of the maritime domain. With recent debate of the LCS’ development, Chuck asks whether the Coast Guard should rethink how it designates its vessels. For the unmanned systems advocates out there, Chuck tells us that the US Customs and Border Protection Agency’s unmanned air systems program has failed to live up to expectations. You can access that post here and further discussion on the topic here.

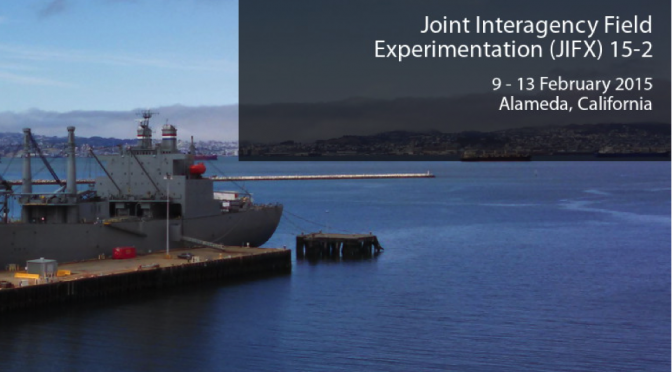

Defence industry has been developing high-tech robotic suits to enhance the capability of the average soldier. There are, however, unrealised potential for ‘exosuits’ or ‘exoskeletons’ exists within HADR and shipborne operations. The Center for a New American Security has recently published a report titled ‘Between Iron Man and Aqua Man’ and was co-authored by our very own Scott Cheney-Peters. This report will certainly open one’s eyes to other applications for the emerging technology beyond its use in combat. You can also see further discussion on the topic in Scott’s post at War on the rocks.

Continuing in the same vein as his ‘Feast of Salami and Cabbage’ article in late 2014, Scott Cheney-Peters, provides clarification to the legal jargon used within maritime disputes. For those without a background in the maritime realm or an understanding of international law this article will provide a layman’s guide to those terms being used by those in the field. This post is the first instalment in a partnership with The National Interest and you can access it here.

Finally, it would not be a CIMSEC roundup without the ‘Pacific Realist’ featuring in the post. Zachary Keck returns with four contributions this week. The first is reporting that the DPRK wants to acquire Russian fighter aircraft. The second post is Keck’s roundup of the top 5 weapons in the US arsenal that Russia should fear. The third reports that there is good evidence to suggest that the DPRK will continue to test nuclear weapons. In the final contribution, Keck summarises the various insights offered during a panel discussion on national security in the changing media landscape. You can access that article here.

At CIMSEC we encourage members to continue writing, either here on the NextWar blog or through other means. You can assist us by emailing your works to [email protected].