This was written as part of our Non-Navies Series AND Matthew Merighi’s “Lessons from History” series.

By Matthew Merighi

In 1538, Christendom assembled one of the largest allied fleets in its history. Called the Holy League to honor its Papal sponsors, it numbered 157 ships and was drawn from many of the strongest maritime powers of the age, including Spain, the Papal States, Venice, and the Maltese Knights of St. John. This motley alliance had one goal: to defeat the fearsome fleet of the Ottoman Empire under the legendary pirate Hayreddin Barbarossa.

The early borders and expansion of the Ottoman Empire. Although a navy would have been useful, it was not necessary as maintaining land-power dominance to control outlying vassal states. As a result, their navy never developed until later years (image from Wikimedia Commons).

The Ottoman Empire was not always a maritime powerhouse. Until the mid 15th century, the Ottomans were best known for their dominant land forces which they used to counter that landpowers in their neighborhood. This all changed under the Sultan Mehmet II, who intentionally increased the size of the navy to fuel his wars of conquest and, specifically, to go after the greatest city in the medieval world.

A map of Constantinople and the infamous anti-access, area-denial (A2AD) chain across the Golden Horn. Mehmet II ordered his army to drag ships across the northern landmass to complete the city’s encirclement and take advantage of the lower walls on the city’s northern expanse (image from Wikimedia Commons).

In 1453, Mehmet II conducted his famous final siege of Constantinople. In order to fully surround the city, he needed to move naval forces into the Golden Horn. Unfortunately for him, the Byzantines used a traditional medieval anti-access/area-denial (A2AD) technology to keep out enemy navies; a massive chain lay across the entire expanse (see map above). To achieve his encirclement, Mehmet ordered his army to physically drag his ships out of the Bosphorus to the east of the city and, using logs as rollers, drag them across the northern landmass and deposit them in the western part of the Horn away from Byzantine forces. The move, though daring, was essential but not sufficient for the defeat of the city. Constantinople fell on 29 May 1453 only after the army breached the supposedly impregnable land walls to the west.[i] Even when it played a crucial role in operations, the Ottoman navy played second fiddle to the army.

An Ottoman galley. Using sails and oars, the galley could keep moving regardless of weather. The banners with the downward crossed swords at the bow and stern are the colors of Barbarossa while the one depicting three crescent moons is the Ottomans’ imperial flag (image from Wikimedia Commons and the Istanbul Naval Museum).

The mainline in the Ottoman navy for most of its history was the galley. For those unfamiliar, the galley was a warship first devised in the Classical era and first made famous in Greece, particularly in its roles in the Persian and Peloponessian Wars in the 300’s B.C. It had two methods of propulsion: sail-power and oar-power. Sails provided the fastest and most efficient speed but, in times of bad weather or no wind, or when rapid movements were needed in close combat, oars provided a useful alternative. Oar-power, while useful, did have a significant drawback: it required a lot of manpower. The Ottomans, however, possessed the bureaucratic acumen to recruit these rowers through a sophisticated administrative and judicial apparatus that levied paid conscripts from provinces around the empire. They divided up recruitment between coastal and inland provinces, leveraging experienced mariners from the coastal levies for work in rigging and the non-maritime minded levies from the inland provinces as rowers.[ii]

Although the 15th and 16th century century saw the rise of the high-sided, sail-powered galleass as a weapon of war, the galley remained a viable military technology throughout this entire period. The galley’s capabilities were not useful on the Atlantic and other harsh ocean waters but, inside the confines of the Mediterranean, their utility was still as manifest in the 1500’s as it was two thousand years earlier; weather was still unpredictable and the Mediterranean, although dangerous, was still not as violent as the deep ocean. Galleys had similar gunpowder armaments as their galleass competitors during this period, so they retained their lethality as well.

While the Ottomans were causing general mayhem for Christendom in the Eastern Mediterranean through the early sixteen century, including the conquest of Venetian islands and the expulsion of the Knights of St. John from Rhodes, another Islamic force caused similar problems on the Western shores. Piracy was rife across the entire Mediterranean but those in the west were of a particular brutal and effective breed. Chief among these brigands were the forces of the pirate brothers Uruj and Hayreddin.

While these two men were the scourges of the western Mediterranean, they were not natives to the region. The brothers lived and conducted piracy in the Aegean with the tacit backing of the brother of the man who would become Selim I, the ruling Sultan. Selim fought a brutal succession war against his brother but emerged victorious and had his brother executed in 1513. Sensing their mortal peril, the young brothers fled to safer waters in the west[iii]. They made a reputation for themselves there as ruthless raiders but also as folk heroes to the Islamic community when they used their fleets to smuggle Muslim refugees fleeing persecution in Spain. Their efforts were so successful that they amassed enough resources, both money and manpower, to conquer the city of Algiers in 1516, establishing themselves as the Sultans of North Africa and converting one the largest cities in the region into their own private pirate base. It is at this time that Hayreddin acquired his nickname Barbarossa (Red Beard) from European commentators.

Charles V of the Habsburg Empire. One of the greatest monarchs in European history, he laid the foundations for the world’s first global empire. A map of his European possessions in 1538 is shown on the right in red with Ottoman holdings in green. His personal motto, “Plus Ultra” (onwards and upwards) still graces the Spanish flag to this day (image of Charles from Wikipedia; map from Griffith University in Australia).

Unfortunately for the brothers, 1516 also marked the accession of a new king in Spain: Charles V. Charles was a young, dynamic leader who wanted nothing more than to establish himself as the universal king of Christendom.[iv] He was expansionist minded and could not tolerate the existence of Barbarossa’s raiding fleets in the south. He organized a counter offensive which, with himself at the head, wrested control of Algiers and other cities from the brothers. Uruj himself died in 1518 while fighting the Spanish, leaving Barbarossa to salvage what he could. Salvation came from an unlikely source: Selim I.

Selim I and Barbarossa both needed each other. Barbarossa was desperate for assistance from whatever source he could find to keep his pirate business turned political empire alive. Selim I, meanwhile, was fighting against the Habsburgs in central Europe and needed to maintain as much pressure on Charles V as he could. Selim I also needed a stronger navy to secure lines of supply and communication between the Ottoman capital and the newly-conquered province of Egypt.[v]

Selim I’s assistance to Barbarossa came with strings attached. Barbarossa lost his political independence but retained control of his territory. While Barbarossa retained OPCON over his forces, they were placed under Ottoman jurisdiction, essentially the medieval equivalent of ADCON.[vi] Imperial inspectors would personally inspect each ship, determine their capabilities, and issue a formal letter authorizing them to operate in certain sectors and solely against targets of states at war with the Empire. [vii] Thus was the transition from pirate to a state-sponsored corsair. For those familiar with navy history at this time, these corsairs were exactly the same as European privateers during this period.

A map depicting the locations of major pirate bases (in black and green) and areas that the Ottomans raided once Barbarossa’s forces were incorporated into the Empire (in red). No one was safe.

The benefits of the partnership paid off quickly. With his newfound resources and top-cover, Barbarossa’s forces were able to push back against the Habsburgs. In the East, Selim I died in 1522 and was replaced with his son Suleyman. Later known as “the Magnificent” and “the Lawgiver,” Suleyman proved a valuable partner and patron for Barbarossa. Suleyman’s forces in the East displaced the troublesome Knights of St. John from Rhodes in 1522,[viii] making them homeless for eight years until Charles V gave them the island of Malta in 1530. Recognizing Barbarossa’s talents and feeling the pressure of Charles V and the other naval superpower, Venice, Suleyman elevated Barbarossa to Admiral of the Ottoman Navy in 1533.[ix] In that same year, the Ottomans concluded a formal alliance with the Habsburg’s perennial European opponent, France.

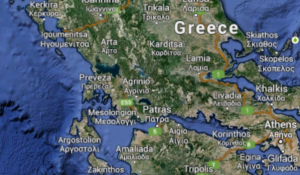

Charles V was in a tough spot in 1537. Ottoman armies were invading through Hungaryhis North Africa campaign was stalling, and he was embroiled in a brutal war against the Ottoman-allied French in Italy. The Reformation was in full swing, undermining his position as the champion of a Christendom united under Catholicism. His Venetian allies were entirely expelled from the Aegean thanks to Barbarossa’s command of the Ottoman fleets in the Eastern Mediterranean. Charles was on the back foot and needed to find a way to put up organized resistance at sea. Using his position as the strongest Catholic monarch and the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles leveraged the Papal States to create a Holy League of naval powers to finally defeat the Ottomans once and for all. This League, founded in February 1538, was placed under the command of the Genoese pirate-turned-admiral Andrea Doria. Doria’s forces trapped Barbarossa and his 122 ships in the narrow strip of water between the north and south halves of Greece, near the city of Preveza. Victory seemed assured.

The straits of Preveza to the left which were the defining strategic moment in the Mediterranean for three and a half decades .

The Battle of Preveza was a disaster for the Holy League. At the outset of the battle, unfavorable winds kept the League’s fleet divided while the Ottoman galleys were still able to maneuver using oar power. Barbarossa, too, outfoxed Doria and seized the initiative despite the Ottomans’ smaller numbers. In total, the League lost 49 ships while the Ottomans did not lose any. The defeat was so lopsided that the Venetians had to pursue a separate peace with the Ottomans in 1540 in which they had to surrender a number of their islands and pay large war reparations. Barbarossa became a rock-star in the medieval naval community. Suleyman made him a permanent member of the Ottomans’ governing council and received fan mail from across Europe, including from the great English privateer Sir Francis Drake.[x] The Eastern Mediterranean was transformed into the so-called Ottoman Lake which freed up additional resources to fight the Habsburgs in the West. The Ottomans, despite their humble beginnings, truly evolved from dragging ships across the land to become the strongest naval power in the Mediterranean.

Lessons Learned

1) Be a realist and do not take things personally.

It would have been very easy for Selim I to get hung up on Barbarossa’s connection to Selim’s executed brother and ignore Barbarossa’s plight in 1518; worse yet, Selim might have welcomed Charles’ efforts against Barbarossa. Instead, Selim recognized a win-win opportunity and incorporated them into the Ottoman fold.

The same thinking goes for Suleyman’s cooperation with Christian France. Without the French causing trouble for Charles V, Barbarossa might have faced even more ships at Preveza and failed to triumph. Realism wins the day.

2) Meritocracy is the best way to select commanders

Just as Selim I could have easily overlooked Barbarossa’s difficult position in 1518, Suleyman could have easily overlooked the corsair for the position of Admiral of the Navy in 1533. The historical precedent was for the governor of the Dardanelles province, with the largest armory and naval base in the Empire, to be the Admiral[xi] but Suleyman took a chance and elevated the former pirate instead. This meant that the brilliant commander was in place for the Battle of Preveza whereas other commander might have failed to deliver a victory.

3) Technology is not enough to win. Also, old technology does not mean bad technology.

The victory at Preveza was only possible because the Ottomans used galleys rather than galleasses. Even though the initial design was pioneered millennia earlier, galley technology still had utility in the strategic game that the Ottomans played. Also, as Barbarossa’s actions against Andrea Doria at Preveza demonstrated, a good commander plays a greater role in a battle’s outcome than numbers or technology.

Matthew Merighi is a civilian employee with the United States Air Force’s Office of International Affairs (SAF/IA) currently transitioning to pursue a Masters’ Degree at the Fletcher School. His views do not reflect those of the United States Government, Department of Defense, or Air Force but is pretty sure the Navy is glad it does not have to fight Barbarossa in his prime.

References

[i] Imber, Colin. The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1650: The Structure of Power. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, p. 28-29.

[ii] Imber 2009, p. 306.

[iii] Imber 2009, 47.

[iv] Fodor, Pal, Geza David, and Gabor Agoston. Ottomans, Hungarians, and Habsburgs in Central Europe: The Military Confines in the Era of Ottoman Conquest. Netherlands: Brill, 2000, p. 154.

[v] Gürkan, Emreh S. ‘The Centre and the Frontier: Ottoman Cooperation with North African Corsairs in the Sixteenth Century’. Turkish Historical Review, 2010, p.132

[vi] For those unaware of the modern military terms, OPCON stands for “operational control” while ADCON stands for “administrative control.” OPCON is given to a person who ADCON denotes who is responsible for ensuring the administrative functions that support forces at sea. Basically, those with OPCON give people orders and those with ADCON tell people when their paperwork is out of order.

[vii] “Corsairs and the Ottoman Mediterranean,” Emrah Safa Gürkan and Chris Gratien,Ottoman History Podcast, No. 76 (October 26, 2012) http://www.ottomanhistorypodcast.com/2011/04/ottoman-mediterranean-corsairs-with.html

[viii] Imber 2009, 49.

[ix] Imber 2009, 51.

[x] “Corsairs and the Ottoman Mediterranean,” Emrah Safa Gürkan and Chris Gratien,Ottoman History Podcast.

[xi] Imber 2009, 297.

This week, Sea Control Asia Pacific brings you a primer on Indonesia: what do its recent elections mean for its global role? The largest state in Southeast Asia as well as a stable, Muslim majority democracy, Indonesia is always said to have ‘great potential’ both as a regional power and global player. With a newly elected president, could Indonesia do more in international affairs? To answer that question,

This week, Sea Control Asia Pacific brings you a primer on Indonesia: what do its recent elections mean for its global role? The largest state in Southeast Asia as well as a stable, Muslim majority democracy, Indonesia is always said to have ‘great potential’ both as a regional power and global player. With a newly elected president, could Indonesia do more in international affairs? To answer that question,

On one side, drug cartels attempt to optimize their operational efficiency while mitigating the risk of detection, seizure, and capture. On the other side, we have law enforcement and militaries’ efforts to improve their surveillance and detection capabilities. This race to out-flank and counteract one another has led to the development of narco-submarines.

On one side, drug cartels attempt to optimize their operational efficiency while mitigating the risk of detection, seizure, and capture. On the other side, we have law enforcement and militaries’ efforts to improve their surveillance and detection capabilities. This race to out-flank and counteract one another has led to the development of narco-submarines. This work is anticipated to appear in the Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) website as unclassified research conducted on defense and security issues that are understudied or under-considered. The work contains a preface written by Dr. James G. Stavridis, and a number of essays written by U.S. Navy Captain Mark F. Morris, Adam Elkus, Hannah Stone, Javier Guerrero Castro, and Byron Ramirez discussing and analyzing narco-submarines. The paper also comprises a comprehensive photo gallery, arranged in chronological order, which allows the reader to observe the evolution of narco-submarine technologies. It also contains a cost benefit analysis of using narco-submarines, as well as a map and a table that highlights where these distinct narco subs were interdicted. The data that we came across seems to propose that cartels have been using different types of narco-submarines concurrently; hence, they seem to be employing a mixed strategy.

This work is anticipated to appear in the Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) website as unclassified research conducted on defense and security issues that are understudied or under-considered. The work contains a preface written by Dr. James G. Stavridis, and a number of essays written by U.S. Navy Captain Mark F. Morris, Adam Elkus, Hannah Stone, Javier Guerrero Castro, and Byron Ramirez discussing and analyzing narco-submarines. The paper also comprises a comprehensive photo gallery, arranged in chronological order, which allows the reader to observe the evolution of narco-submarine technologies. It also contains a cost benefit analysis of using narco-submarines, as well as a map and a table that highlights where these distinct narco subs were interdicted. The data that we came across seems to propose that cartels have been using different types of narco-submarines concurrently; hence, they seem to be employing a mixed strategy.