By The Naval Constellation

The Naval Constellation is an online, unofficial forum resident on the team communication application Slack. The group includes Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard officers, enlisted, and civilians, and serves as a place to break down organizational silos and facilitate conversation on topics ranging from innovation to strategy, emerging technology, and more. While it has existed and grown for six years, we are now partnering with CIMSEC on an enduring public series, “@Channel,” to be published as the conversation warrants it. Contact information to join future conversations like this can be found at the bottom of the article.

The below is a discussion from the Constellation between 11 participants identified by first name. It has been lightly edited for clarity. All content is submitted with the participants’ consent.

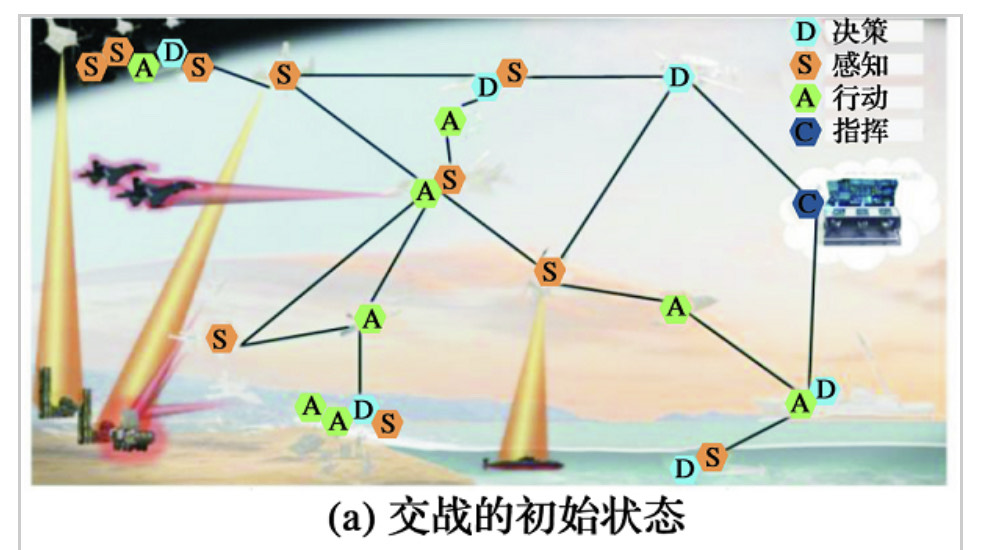

Shane: @channel, Kyle and I are discussing how the Joint Force ought to think about warfare as disabling or breaking down kill webs rather than kill chains; that these webs should be thought of almost as complex adaptive systems (CASs), not multiple reducible chains of effects. What’s the best mental model for attacking or defending against kill webs in war?

Jason: Kill chains are single path, unidirectional, and fairly fragile. Kill webs are multipath, multi-directional, and resilient. To take out a web you have to affect the node and surrounding nodes… That means you need to affect proximal relationships, not just specific targets. Counterintuitively, precision fires don’t work on kill webs. You need an area of effect and less precise methods.

Throw a rock through the spider web, don’t clip individual strands.

Chris: I think of kill chains as being the decision process. We are hindered by the chain of command and decision process that is fragile effect and does have a single path. Kill webs are what Jason described above, but they are aspirational right now. I’d argue that most of our systems are not part of kill webs and are still really fragile. Are we that adaptive? Do our systems actually work that way outside of a very structured exercise?

And if they are, will our Command and Control (C2) process actually let us operate like that?

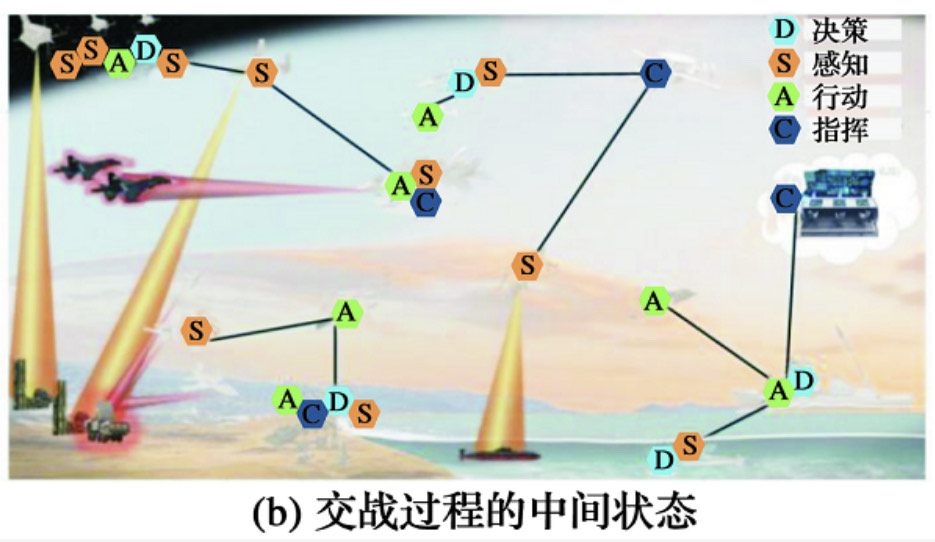

Jason: Kill webs take a lot of energy to maintain. They are resilient, but if disrupted are more difficult to restore. I recommend a hybrid approach.

Kyle: Would you describe China’s A2AD networks as kill webs? Is there any difference?

Jason: Certainly. Highly resilient, taking out a single node won’t affect the web, but a significant enough, broad disruption, and the system would be hard to reconstitute.1

Chris: Jason, do you design a kill web so that it fails to a chain? Or do you choose what systems are part of a web and which are a chain?

Jason: It needs to fail to chains. That’s essentially what graceful degradation is… The reduction of nodal complexity until the issue is solved. Isolate the system, identify the problem, and reconstitute the system. For example, we should actually practice moving from battlegroup, coordinated operations to a unit, disconnected independent ops, and back again. The back again shouldn’t be “the network is back.” That’s unrealistic.

Instead, its independent ops, becoming two ships talking, becoming a group of ships coordinating, becomes battlegroup operations.

We actually do this in damage control. Think about engineering redundancy. We make the system more complicated than it has to be by building redundant systems. Two of the same system with a series of crossovers and disconnects. If something leaks in the system, you can isolate a portion without fully shutting down the system. You may have some penalties to efficiency… Can only operate with a 50% flow rate for example… But the system keeps working and furthermore… The degradation makes the system simpler to troubleshoot and operate.

Shifting back to the more complex operations should be deliberate – just because you fixed one thing, doesn’t mean there aren’t secondary issues you will find when you bring it back up to a higher level of complexity… Open the isolation valves too fast and you end up with 100% flow against potential unknown issues you haven’t fixed yet.

Shane: Do we do enough to train the Information Warfare Community (IWC) in how to understand and potentially disrupt, degrade, deny or destroy complex systems like kill webs?

Ryan: We absolutely do not do enough to train the IWC in this.

That’s the issue with webs and warfare at the liminal edge. We believe that shooting a few multimillion-dollar surface-to-air missiles (SAM) at an ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance) drone is Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO), or that mixing up a CVW (Carrier Air Wing) composition enables more resiliency. Neither are webs – they are chains – and we think of warfare in a chain mentality.

The Navy fundamentally lacks the ability to see outside the cave and assess how cyber or info ops might result in degraded C2 from a geographic node in the web. Or space-based effects. Nor would JFMCCs (Joint Force Maritime Component Commanders) know how to employ that kind of stuff at the Fleet or AOR (Area of Operations) level.

Kurt: I’d argue no one in the USG (United States Government) can assess cyber ops, and no one in the US military (except maybe the bubbas at CYBERCOM) trust that cyber can reliably deliver the right effect at the right time for cyber to be selected before a traditional kinetic option is selected.

Ryan: I think breaking up kill webs requires a truly joint effort. That’s not something we can expect our CSGs (Carrier Strike Groups) or single DDGs (Guided Missile Destroyers) to determine and execute alone.2

China, on the other hand, does this really well with its joint structure and national technical means. We would do well to think on how that can be broken down, and how a similar construct “with American characteristics” might be developed to serve attacking CASs.3

Kyle: So as much as I understand the concepts we’re applying here, what I struggle with is assigning the WHAT to invest in and WHO needs WHAT training.

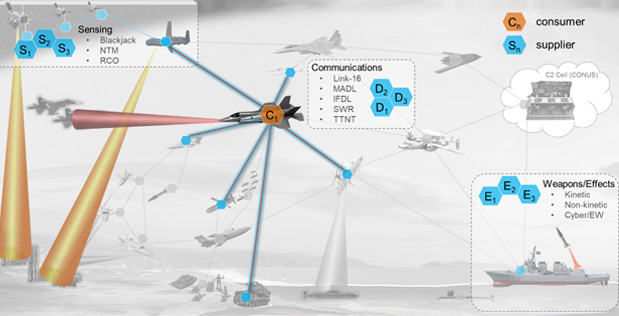

Is this Fleet staffs? Individual ships or units? Everyone? What are we buying that would turn our chains into webs, and is that even feasible with our current acquisition process? Isn’t a “Cloud of Fire Control Data” sort of what you want?4

Kurt: I think the Navy can’t do it alone.

Alex: Kurt, because the Navy doesn’t have the assets to populate a web, i.e. “this is inherently ‘Joint’”? Or because culturally the Navy is resistant to implementing the organizational changes to exploit a web should it exist?

Ryan: Yes to both.

Kurt: Maybe I don’t know what you all mean by “web.” I’m assuming you mean some ultra-resilient system (like a mesh network) exists that can absorb significant damage before a worrisome degradation of capability occurs. And if that damage isn’t adequately and appropriately applied, the system would shrug off the attack with very little actual impact to the overall system.

Kurt: I said the Navy can’t do it alone because the Navy almost assuredly doesn’t have the fielded capabilities to unilaterally destroy what I (perhaps incorrectly) am assuming is a multi-domain, multi-modal “kill web.” Ignoring everything else, the way the DoD (Department of Defense) allocates (or doesn’t, as it happens) cyber forces would preclude Navy cyber from having a major role in fights occurring outside certain geographic boundaries.

Alex: Ah, the Navy can’t attack/dismantle an adversary kill web alone. I think there’s a parallel discussion about implementing and using blue force kill webs.

Louis: I like the term “ecosystem”, which brings to mind perhaps “full-spectrum ecological attack” or something. Military eco-collapse.

Matt: I think that the idea of webs will require different C2 and ways to think about sensor/weapon/target pairings. We can’t allocate a set of assets for a single or small set of targets unless we want a very narrow web.

I think that chains can be a way to test and think about paths through the web but they’ll always need to have follow-up analysis as a web. In aerospace engineering (AE) we used to have a joke that you know you’re an AE if you’ve represented a wing as a plane, the plane as a line, and the line as a point (to simplify the calculation). The same holds, you can test paths through the web exquisitely using analysis and might have to run exercises as exquisitely planned chains or small webs, but we should war game and do larger [Modelling and Simulation] as webs. I worry about webs though, if we need the always-on comms to make them work. That means they’re fragile and our already targeted comms infrastructure will be an easy point of failure.

Mike: In my mind, having multiple comms channels is part of what would make a web a ‘web’.

Matt: I agree, but those might be very low bandwidth or short duration or one way rather than bi-directional. We don’t just turn on “Uber comm path 1” and know that will link everyone with the same protocols.

Mike: It worked in World War Two, some of the naval battles in the Slot [during the Guadalcanal campaign] came down to real-time unencrypted bridge-to-bridge radio to share info across the Fleet rapidly.

Matt: Absolutely think of them as complex adaptive systems, but if you do then you have to accept that any given path through the web might not give you the same performance twice, or that the assets you thought you’d have for a given mission might be taken over by another use of the web. This is where the joint piece comes in, the bigger the web the more possible elements in any given role/roles.

Practicing as a web will be hard though. We need MMO (massively multiplayer online) wargaming that is always on. I should be able to log in with the rest of my DDG or on my own, and should be able to find other players online. We would also need some way to figure out classification so we could play red as accurately as possible without giving up methods and sources. We should have stats that we can download and leader boards and tutorial sessions that are always available. Have practice where people can try out ideas free of criticism and then have more serious competitions where people are graded and that data-rich environment is plumbed to find out how to do better.

This is going to be expensive, in terms of dollars and resources, but would be well worth it. We could/should have layers of detail, so someone can play a simpler game against

Others in one on one or play in very detailed complex many on many battles.

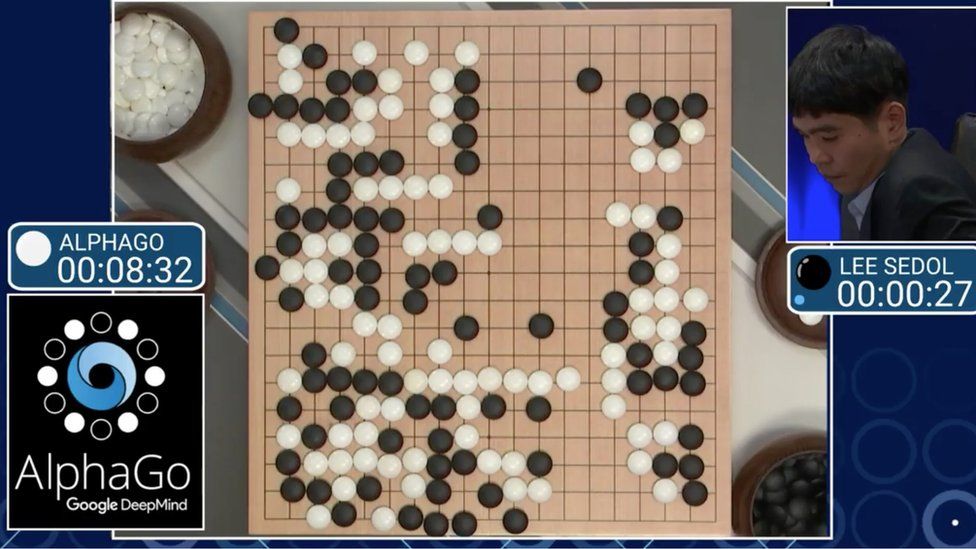

Nick: Agreed, and you can’t benefit from AI-enabled reinforcement learning (think AlphaGo)5 to make tactical and operational recommendations without building a robust modeling and simulation environment first.

So, this virtual environment has to essentially mirror the real-world COP (Common Operational Picture), or at least have exposed APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) that are formatted similarly, so you can train a model in a simulated environment and immediately deploy that same model into an operational context.

Matt: Use peoples’ play to train the AI as you go?

Nick: You could do it either way. You have a rewards/punishments system, where let’s say people play China, and fight to China’s tactics and capabilities. A model can then iterate through millions of blue force responses to find the one with the highest probability of success and make those as recommendations. Another method is you can program China’s tactics in as broad rules, but have it be an AI instead of people, so the two models learn from each other. The reason for machine learning is that there are so many exponentially complex scenarios in the responses, you can’t necessarily try all of them every time, so you train a model that can estimate the best response without needing to try every scenario. That was the significance of the AlphaGo achievement in beating the world champion at Go.6

Once a model is trained though, you can deploy it to look at real-world situations and make recommendations for blue force actions based on its training in the simulated environment.

Alex: I think this is the end state that LVC (Live, Virtual, Constructive) training should aim for. Imagine if off each coast there was a persistent virtual battlespace that you could “log” into, either with a ship, aircraft, or submarine (not sure how LVC is thought to work for subs, if at all).

Nick: Also, having no experience or interaction with JADC2 (Joint All-Domain Command and Control), would someone mind explaining how that initiative relates to the kill web concept?[7] I was under the impression that the JADC2 initiative was trying to help solve that problem.

Shane: JADC2 should, in theory, give you the technical ability to link together currently non-compatible networks, sensors, and weapons systems. But from what I can gather JADC2 is pretty much only about that technical ability. There’s no attempt to get people to conceptualize attacking webs as opposed to just attacking a series of chains. That’s not really a technical thing, it’s more a doctrine, training, and TTPs (Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures) thing.

That half seems to be sorely lacking.

If you would like to join the conversation at the Naval Constellation, please email: [email protected].

Endnotes

1. “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2020, Annual Report to Congress.” Office of the Secretary of Defense. https://media.defense.gov/2020/Sep/01/2002488689/-1/-1/1/2020-DOD-CHINA-MILITARY-POWER-REPORT-FINAL.PDF

2. Captain Carmen Degeorge, U.S. Coast Guard, Commander Nathaniel Schick, U.S. Navy, and Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Wilson And Majors Chad Buckel And Brian Jaquith, U.S. Marine Corps. “Naval Integration Requires A New Mind-Set”. 2021. U.S. Naval Institute. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2021/october/naval-integration-requires-new-mind-set-0.

3.” Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2020, Annual Report to Congress.” Office of the Secretary of Defense. https://media.defense.gov/2020/Sep/01/2002488689/-1/-1/1/2020-DOD-CHINA-MILITARY-POWER-REPORT-FINAL.PDF

4. Shelbourne, Mallory. 2020. “Navy’s ‘Project Overmatch’ Structure Aims To Accelerate Creating Naval Battle Network – USNI News”. USNI News. https://news.usni.org/2020/10/29/navys-project-overmatch-structure-aims-to-accelerate-creating-naval-battle-network.

5. “Google AI Defeats Human Go Champion”. 2017. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-40042581.

6. Ibid.

7. “Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2)”. Congressional Research Service. July 1, 2021. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11493

Featured Image: PHILIPPINE SEA (Jan. 22, 2022) An F-35C Lightning II, assigned to the “Black Knights” of Marine Fighter Attack Squadron (VMFA) 314, and an F/A-18E Super Hornet, assigned to the “Tophatters” of Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 14, fly over the Philippine Sea. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Haydn N. Smith)